Émile Dorand

Jean-Baptiste Émile Dorand (born 14 May 1866, died 1 July 1922), was a French military engineer and aircraft designer.

Émile Dorand | |

|---|---|

| Born | 14 May 1866 |

| Died | 1 July 1922 (aged 56) Paris. France |

| Nationality | French |

| Occupation | Military engineer, aircraft designer |

Early career

Émile Dorand was born in Semur-en-Auxois in eastern France. He attended the École Polytechnique from 1886 to 1888 in the Latin Quarter of Paris. He then went to the Fontainebleau Application School, a military college, which he left after two years as a Lieutenant in the French Army. In an engineering regiment, he met the airship pioneer Charles Renard, and was soon authorised to direct free balloon flights. He studied aeronautics and the problems of flight including working to improve kites, long range photography, and flight test methodology.[1]

From 1895 to 1896, he was assigned to the Expeditionary Engineer Corps with whom he managed hydrogen balloons and bridging equipment in Madagascar. He returned to France as a Captain, and was posted to Avignon, Dijon and Versailles.[1]

Aircraft development and design

In 1907 he moved to the Research Laboratory for Military Ballooning which became the Laboratory for Military Aeronautics, where he chaired the Engineering Study Commission in 1908.

In that year he patented the design of an undercarriage shock absorber, which appears to be present on his powered kite or Dirigible Biplane, possibly named the Laboratoire, of 1909. which completely failed to fly.[2] In 1910 he patented a link between an aircraft and its nacelle (in this context, fuselage).[1] Both of these ideas were probably incorporated into his powered kite projects, where a steerable tractor engine and propeller were attached to a fuselage (nacelle) suspended from a large biplane or triplane kite. Dorand developed these in the period from 1908-1910.[3]

In 1912 he became an engineering battalion commander and head of the Military Aeronautical Laboratory at Chalais-Meudon. In 1914 he became its director, but it was closed in 1915 because of the First World War. In 1913 he developed the DO.1 two-seat armoured reconnaissance biplane, which was a successful design but severely underpowered.

On 28 February 1916 the by now Lieutenant-Colonel Dorand was appointed as the first director of the Service Technique de l'Aéronautique (STAé). One of his responsibilities was the drawing up of specifications of aircraft for the French military forces.[1]

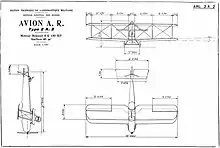

During 1916 he designed, in conjunction with Captain Georges Lepère, the AR.1 and subsequently the AR.2, which had reduced wing span and different engines. The ARs were much more successful than the DO.1, on which they were based. All these aircraft had distinctive negative stagger biplane wings, and the fuselage was mounted on struts between the wings.

In the same year Dorand collaborated with Émil Letord in the design of the Letord Let.1 three-seat twin-engined reconnaissance biplane, which featured Dorand’s negative stagger biplane wings. This led to a successful series of aircraft, built in the government factories at Chalais-Meudon and in the factories of Farman and Letord, ending with the Let.7.[4] Over 250 examples were built by the end of the First World War, including 142 used as trainers by the American Expeditionary Force.[5]

Postwar career

Dorand left the STAé on 11 January 1918, and was appointed the Inspector General of Tests and Technical Studies at the French Ministry of War. Less than a year later he was promoted to Colonel and became the head of the French delegation of the Interallied Commission for Aeronautical Control in Germany. In this role he was responsible for searching the defeated country for anything of aeronautical interest that could be brought to France. He was also responsible for inspecting facilities to ensure that the Treaty of Versailles restrictions on German aeronautical activities were being observed. During these activities he courted controversy by suggesting that Hugo Junkers be brought to France to assist in the development of metal aircraft construction techniques. The press called into question Dorand's reputation, considering his plans a wasteful expansion of the air fleet for a country that now considered itself to be at peace.[1]

Private life

He married Jeanne Marguerite Devanne in April 1897. They had one son, René Dorand, born in 1898, who from 1931 to 1938 worked with Louis Charles Breguet on the development of helicopters, particularly the Bréguet-Dorand Gyroplane Laboratoire. He also wrote press articles attempting to restore the reputation of his father, recalling his important advances in French aeronautics. Émile died in Paris on 1 July 1922.[1]

List of aircraft designs

- Powered kites series 1908-1911[6] possibly including the Dorand 1908 Avion Militaire

- Dorand Laboratoire series from 1908 to 1912[6]

- Dorand 1911 biplane

- Dorand DO.1 (1913)

- Dorand Armoured Interceptor (1913)[7]

- Dorand-Bugatti BU (1915) negative stagger triplane bomber project with two Bugatti engines. The engines were a failure and the project was abandoned.[8]

- Letord Let.1 to Let.7 series (1916)

- Dorand AR series (1916)

- Dorand flying boat (date unknown) A negative stagger biplane project with the engine buried in the streamlined fuselage, driving twin pusher propellors,[7] Probably not built.

References

- "Fonds Emile Dorand (PDF in French with transcript)". Docplayer.fr. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- "Dorand Aeroplane Dirigeable Biplane". Getty Images. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- "Les debuts de l'aviation á Semur de 1911 (in French)" (PDF). Aéroclub de Semur-en-Auxois. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- Taylor, John WR (1969). Combat Aircraft of the World. London, UK: Ebury Press and Michael Joseph. p. 101. SBN 7181 0564 8.

- "Dorand AR.1/AR.2". Airplane. 7 (79): 2209. 1990.

- "L.Opdyke - French Aeroplanes Before the Great War". Their Flying Machines. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- "Émile Dorand Airplanes and Projects". Secret Projects Forum. Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- "Les hydravions d'Alphonse Tellier by Gérard Hartmann (PDF in French)". La Coupe Schneider et Dossiers techniques aéronautiques. Retrieved December 30, 2019.