1st Louisiana Regulars

The 1st Louisiana Regulars Infantry Regiment, often referred to as the 1st Louisiana Infantry Regiment, was an infantry regiment from Louisiana that served in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War.

| 1st Louisiana Regulars Infantry Regiment | |

|---|---|

Battle flag of the type issued to the regiment as part of Bragg's corps | |

| Active | February 1861 – May 1865 |

| Country | Confederate States of America |

| Allegiance | Louisiana |

| Branch | Confederate States Army |

| Type | Infantry |

| Size | c. 860 (March 1861)[1] |

| Engagements | |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | |

Raised in early 1861 in New Orleans, the regiment was sent to Pensacola and served there as cannoneers for the Confederate batteries. Transferred to the Army of Mississippi in March 1862, the 1st Louisiana Regulars suffered heavy casualties in the Battle of Shiloh. After participating in the Siege of Corinth and the Confederate Heartland Offensive later that year, the regiment became part of the Army of Tennessee when the Army of Mississippi was renamed in November. After further losses at the Battle of Stones River, the regiment was placed on provost duty, being briefly consolidated with the 8th Arkansas Infantry Regiment to fight in the Battle of Chickamauga in September 1863. In early 1864 the 1st Louisiana Regulars were attached to Randall Gibson's brigade, which they served with for the rest of the war, fighting in the Atlanta campaign, the Battle of Nashville, and the Battle of Spanish Fort before they surrendered at the end of the war.

Origins

Following the victory of Lincoln in the 1860 election, Louisiana Governor Thomas O. Moore moved rapidly to assure the secession of his state from the union. In early December, he called a special session of the state legislature, which arranged for the election of delegates to a secession convention and acceded to his request to create a special military board responsible for arms purchasing and distribution in addition to authorizing the funding of volunteer companies, at least one for each parish.[2] Among the members of the military board were sugar planter and former army officer Braxton Bragg, a veteran of the Mexican–American War,[3] and lawyer and cotton broker Daniel W. Adams, who had no military experience.[4]

After South Carolina became the first state to secede on 20 December, Moore ordered the seizure by militia of the Federal Baton Rouge Arsenal and Barracks, Forts Jackson, St. Philip, and Pike, as well as the army barracks below New Orleans on 8 January. The forts were quickly handed over by the lone ordnance sergeants in charge of them on 10 January and Bragg forced the surrender of the outnumbered arsenal garrison on the same day.[2] Meanwhile, militia officers Charles MacPherson Bradford, a district attorney,[5] and John A. Jaquess (sometimes spelled Jacques), a police officer and former filibuster, each raised companies that were initially known known as the 1st and 2nd Companies of the Louisiana Infantry.[6] These companies were officially authorized under a plan to raise 500 regulars for four-month terms of service on the next day.[7] Bradford and Jaquess had both served as junior officers in the Mexican–American War.[5][8]

Bradford took control of the New Orleans Marine Hospital at the New Orleans army barracks on 12 January and had its patients removed to another hospital in order to free space for newly mustered in regulars, an action much sensationalized in Northern newspapers. Moore authorized the enlistment of Bradford and Jaquess' companies as Companies A and B, respectively, of what was designated as the 1st Regiment, Louisiana Infantry, which also contained three other newly organized companies, by 25 January. These companies relieved the militiamen in their occupation of the forts and the Baton Rouge Arsenal and Barracks. The state convention officially voted to secede on 26 January, although Moore's actions had already essentially taken the state out of the Union, and Louisiana almost immediately joined the Confederate States of America.[9] In response to the secession vote, Moore ordered the seizure of the only remaining unoccupied Federal post, Fort Macomb, which was carried out on 28 January by a Captain Henry A. Clinch's Company C of the 1st Louisiana.[10][11]

Formation

The 1st Louisiana Regulars were organized on 5 February 1861 in accordance with an ordinance passed at the state secession convention to establish the Louisiana State Army, a standing army under Bragg's command consisting of an infantry and an artillery regiment modeled on the United States Regular Army, subject to the same discipline as a regular unit. The ordinance stipulated that the infantry regiment would include eight companies with ninety privates each in addition to officers and sergeants.[3][12] The men of the regiment enlisted for three years of service rather than the single year of the volunteers, and unlike the latter, could not elect their own officers. Instead, Adley H. Gladden was appointed colonel, Adams lieutenant colonel, and Bradford major. Gladden had commanded a regiment in combat during the Mexican–American War. Recruited in New Orleans,[13] the regiment included a large number of immigrants, and was described by one soldier of the 19th Louisiana as being "composed exclusively of Irish".[14] Immigrants joining the Louisiana Regulars were often unskilled laborers in civilian life, which placed them at the bottom of the social hierarchy, resulting in economic motivations for enlistment and willingness to enlist for long service terms, in contrast to volunteers.[15]

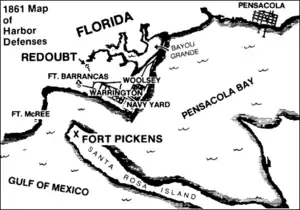

With a strength of roughly 860 men, the regiment transferred to the Provisional Army of the Confederate States on 13 March. During this period the men who enlisted in January were discharged, including those of Jaquess' company, and new companies raised to replace them.[16] By April, prospective recruits were enticed by the reduction of the enlistment term to one year, standard for volunteer units, and a $10 bounty.[17][18] In early April, the regiment was ordered to Pensacola on the Florida Gulf Coast where the Confederates were blockading Union-held Fort Pickens, after the latter received reinforcements, breaking an understanding between the garrison and the Confederates that the garrison would not accept reinforcements if they were not attacked.[19] Due to these movements, the strengths of the Union garrison and the Confederate forces under the command of Bragg at Pensacola were nearly equivalent, resulting in demands from the Confederate government for troops to augment Bragg's force.[20]

The dispatch of the regiment was initially opposed by Moore due to his fears that the Union would attack New Orleans, but Confederate Secretary of War LeRoy Pope Walker's insistence that the threat was nonexistent prevailed.[21] As only Companies A, B, and C had finished recruiting, Moore appealed to volunteer units to complete the regiment. The three complete companies departed for Pensacola on 11 April, followed a week later by the five volunteer companies that responded, the recruitment being aided by a surge in enlistments after the Confederate firing on Fort Sumter began the war in earnest.[22] The companies spent the next several weeks drilling after their arrival in Florida. The remaining seven companies of the 1st Regulars arrived at Pensacola by late May, the regiment having been expanded to ten companies in keeping with standard Confederate practice, and the volunteers were transferred to Virginia as the 1st Louisiana Infantry Battalion.[1]

Pensacola

As 1861 turned to summer and then fall, the 1st Louisiana Regulars continued drilling while serving as cannoneers for the heavy artillery batteries at Pensacola in rotations. Bragg took care to avoid provoking military action, ensuring that Pensacola remained a quiet sector during this period.[19] A series of command changes began when Bradford resigned on 23 July, resulting in the promotion of Company D commander Jaquess to major. Gladden was promoted to brigade command on 10 September and succeeded by Adams, allowing Jaquess to move up to lieutenant colonel and Company A commander Frederick H. Farrar to major.[1]

After the privateer schooner Judah was burned in a Union raid on the night of 13 to 14 September, Bragg launched a retaliatory sortie against the Union troops on Santa Rosa Island on the night of 8 October. Companies A and B of the 1st Louisiana formed the 400-man 2nd Battalion of the thousand-man force commanded by Brigadier General Richard H. Anderson together with three companies from the 7th Alabama and two from the 1st Florida.[23] The battalion, led by Colonel James Patton Anderson, landed from a steamer along with the rest of the force on a beach four miles east of Fort Pickens. Patton Anderson was directed to advance south through the waist of the island and then turn west when he reached the south beach. This movement aimed to capture the Union pickets and isolate Fort Pickens from the camp a mile east of the fort where half of the 6th New York Infantry were located.[24]

After a picket discovered the Confederate approach early in the morning of 9 October, the camp was charged by Colonel John K. Jackson's battalion and its occupants fled. Patton Anderson's troops joined Jackson's in looting the abandoned tents, while Union forces from Fort Pickens responded. To avoid being cut off, the Confederates retreated back to the beach to depart, but were delayed by a jammed propeller on one of the transports, allowing the Union pursuit to catch up. Crowded onto the decks of the transports, the Confederates were subjected to a withering fire, which they returned, and were able to get out of range after the propeller was freed.[25] Company B lost one man killed, one died of wounds, and one severely wounded.[23]

The Union commander struck back with a bombardment against the Confederate positions on 22 and 23 November. Companies G and H and a detachment of the regiment, all under the command of Jaquess, manned the batteries at the Navy Yard and opened up a return fire,[26] but did not inflict much damage on Fort Pickens due to lack of gunnery practice caused by shell shortages. Adams held the troops not needed to serve the guns in readiness to repulse a possible Union landing. Fort McRee suffered severe damage,[27] but the Navy Yard batteries were relatively untouched.[28] Pensacola remained quiet for the next few weeks until 1 January 1862, when a steamer docking at the Navy Yard drew Union fire, causing the inebriated Richard Anderson, in command while Bragg was away on inspection, to order a return bombardment. When Bragg returned he reprimanded Anderson, who had apparently forgotten about the inferiority of the Confederate artillery exposed in the November exchange, for wasting ammunition.[29][30]

Shiloh

Movement to Corinth and scouting

After the fall of Fort Donelson on 16 February, the Tennessee River was opened up for a Union advance against the critical rail junction of the Memphis and Charleston and the Mobile and Ohio Railroads at Corinth, Mississippi.[31] To prevent the capture of Corinth, which linked the Atlantic and the Mississippi River, the Confederate forces at Pensacola were ordered to be pulled out and sent to Corinth, where the Army of Mississippi was to concentrate under Albert Sidney Johnston.[32] Delayed by heavy rains that washed out bridges, the 1st Louisiana Regulars entrained aboard the Mobile and Ohio on 27 February, together with the 18th and 22nd Alabama.[33] The regiment arrived at Corinth by 9 March, when they were assigned with the 18th and 22nd Alabama to a brigade under the command of Adams as Gladden was given command of the division composed of the troops from Pensacola.[34] At Corinth many of its men got drunk after boring holes in the floors of saloons to get at whiskey barrels and made mayhem, being punished by bucking and gagging.[14]

When Lew Wallace's division debarked at Crump's Landing on 13 March, Adams led a detachment that reconnoitered the Union positions, burning cotton bales owned by Unionists.[35] Wallace sent out cavalry on the same day to conduct an expedition towards the Mobile and Ohio Railroad near Purdy, Tennessee, where Gladden had stationed 700 infantry of the regiment and the 22nd Alabama; the cavalrymen skirted Purdy to damage a bridge before Wallace reembarked.[36][37]

William Tecumseh Sherman's division, attempting to cut the Memphis and Charleston Railroad, landed at Tyler's Landing near Yellow Creek on 14 March, sending out companies from the 5th Ohio Cavalry to conduct reconnaissance.[38] The latter drove in the pickets of Jaquess' detachment of the regiment watching the area. Jaquess decided not to engage due to the small size of his force and retreated to Farmington due to lack of rations and heavy rains.[39] The rains made the roads in the area impassable, forcing Sherman to turn back before achieving his objective.[40] In the next two weeks, five divisions of Ulysses S. Grant's Army of the Tennessee encamped on the western bank of the Tennessee River at Pittsburg Landing, but the Union troops did not entrench, not expecting an attack. There, they awaited the arrival of Don Carlos Buell's Army of the Ohio pending an attack on Corinth.[41]

Prelude and 6 April

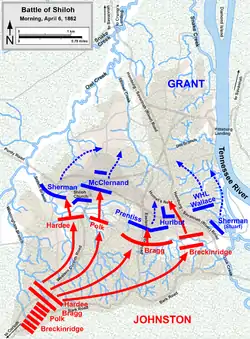

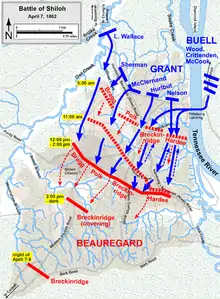

Johnston decided to attack before Buell could arrive, and on 3 April the regiment left Corinth with the army.[42] For the Battle of Shiloh, the regiment was part of Gladden's brigade of Brigadier General Jones M. Withers' division of Bragg's corps, together with the 21st, 22nd, 25th, and 26th Alabama.[43] After marching along crowded, packed roads, Bragg's corps arrived in its starting positions for the battle on 5 April. The corps was tasked with attacking behind William J. Hardee's corps against the Union left to turn the opposing flank and cut Grant's army off from the Tennessee River. Gladden's brigade moved forward to take position in Hardee's line, partially filling a gap between the end of the latter and Lick Creek, with the 1st Louisiana positioned on the far right.[44]

When Gladden's brigade began its attack around 08:00 on the next morning against Colonel Madison Miller's brigade of Benjamin Prentiss' division, the Union troops were not surprised as the battle had already been in progress for some time. Advancing toward the open Spain Field up a gradual rise, the brigade was exposed to volleys from Miller's brigade, which inflicted heavy losses. Gladden was mortally wounded leading the 26th Alabama, which had become disorganized due to the terrain in the march to the battlefield and come up on the right of the 1st Louisiana.[45] Adams took command of the brigade, which retreated under the pounding, covered by Robertson's Alabama Battery.[46] In the absence of Jaquess, Farrar became acting regimental commander.[47]

Chalmers' brigade came up on the right, outflanking Miller, and Adams, holding the colors of the 1st Louisiana, ordered an advance at the double-quick against the 18th Missouri and 61st Illinois on Miller's right, supported by the fire of Robertson's battery. The outnumbered Union troops broke under the pressure of Chalmers' and Gladden's brigades, abandoning their tents, where men of the 1st Louisiana captured seven stands of colors. The regiment lost 28 killed and 89 wounded in the initial fighting; among the dead was Company G Captain John Thomas Wheat, the former secretary of the Louisiana secession convention.[1][45] Prentiss' division quickly unraveled and the Confederates paused to loot the abandoned camp.[48]

Johnston, moving forward to direct the action, incorrectly believed that he had found the Union left and began the anticipated turning movement. Gladden's brigade was ordered out of the camp shortly after 09:00 and pushed forward to exchange fire at long range against W. H. L. Wallace's division, deploying for battle. After Johnston learned of Gladden's wounding, he pulled the brigade back and replaced it with John K. Jackson's brigade. The brigade, positioned in reserve in Prentiss' camp to reform,[49] later formed square in the erroneous anticipation of a Union cavalry attack.[50]

In the next several hours the regiment and its brigade replenished their ammunition. Adams was wounded about 11:30 and command of the brigade fell to 22nd Alabama Colonel Zachariah C. Deas.[51] In the late afternoon, the brigade participated in the flanking and encirclement of Prentiss' reformed division at the Hornet's Nest, with the 1st Louisiana being ordered to advance by Bragg with the exhortation "My old bodyguard I see your ranks are thinner but enough are yet left to carry your flag to victory—Forward". They ran into stubborn resistance, but Prentiss' encircled troops surrendered around 17:30.[52]

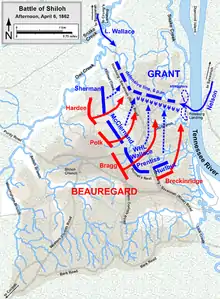

As the day came to a close, the 1st Louisiana and 22nd Alabama left behind the other three regiments and advanced under Deas' command when Bragg ordered a final assault at 18:00, with the Louisianans on the right to the left of Jackson's brigade. They crossed the deep Dill Branch ravine, "hugging the ground" to dodge artillery fire, which stopped forward progress.[53] General P. G. T. Beauregard, who had taken command of the army after Johnston was mortally wounded in the afternoon, soon ordered a halt to rest for the next day. With the regiments exhausted and low on ammunition,[54] Deas encamped the two regiments to the rear for the night, finding the Louisiana Regulars with just 101 men present for duty and the 22nd Alabama similarly reduced.[51]

7 April

While the Confederates spent a wet and uncomfortable night, Buell's army and Lew Wallace's division reached the field, the latter from Crump's Landing.[55] The Union troops counterattacked on the morning of 7 April and Deas brought the 1st Louisiana and 22nd Alabama up on the left of Colonel Robert Russell's Tennessee brigade after 10:00, holding the far left of the Confederate line west of the Jones Field towards Owl Creek with the regiment still to the left of the Alabamians. Bragg, separated from his corps, commanded the troops on this section of the Confederate line,[56] and Russell took command of a composite division that included the regiment.[57]

Deas' regiments were advancing when skirmishers from Lew Wallace's division outflanked them, forcing a retreat. In intense fighting amidst the hills and valleys of the Crescent Field, they engaged two brigades of Wallace's division for half an hour, with attacks failing against the weight of the Union numbers. The regiments were steadily forced back until 13:00, when Wallace outflanked them again. Falling back, they participated in Beareaugard's final attack launched at 16:00, buying time for the Confederate retreat, with Deas' command reduced to roughly 60 men.[51] With the army, the 1st Louisiana retreated back to Corinth, unpursued by the victorious Union troops.[57] In the two days of the battle, the regiment suffered 232 casualties.[58]

Corinth to surrender

After the Battle of Shiloh ended, Adams never returned to the 1st Louisiana Regulars, being promoted to command of another brigade. Jaquess succeeded him as colonel on 23 May, with Farrar becoming lieutenant colonel and Company F Captain James Strawbridge major. The regiment went on to participate in the Siege of Corinth between 29 April and 11 June before retreating with the army to Tupelo, Mississippi. By 30 June, the regiment was assigned to Colonel Arthur M. Manigault's brigade of Withers' Reserve Corps as part of Bragg's army, but was on detached duty.[59] In July, Bragg entrained the infantry of the army for Chattanooga, Tennessee via Mobile, while the regiment marched there overland with the army wagon trains.[1] When the 21st Louisiana Infantry Regiment, its strength much reduced by disease and desertion, was disbanded by Bragg's order on 25 July, the 1st Louisiana Regulars received at least 99 men from the regiment. These men ultimately proved unreliable as a high percentage of them later took the oath of allegiance to the Union after being captured.[60]

The 1st Louisiana Regulars were part of Withers' division during the Confederate invasion of Kentucky between 28 August and 19 October. It missed the Battle of Perryville because Withers' Division was detached to support other Confederate forces near Lexington on the day before Perryville, 7 October. The regiment retreated into Tennessee with the army and encamped at Tullahoma. It suffered 102 casualties at the Battle of Stones River between 31 December and 2 January 1863. Farrar was mortally wounded in the battle and died the day after it ended. For his conduct at Stones River, Jaquess was court martialed and cashiered on 13 February, being replaced as colonel by Strawbridge. Strawbridge, having moved up to lieutenant colonel after Farrar's death, became the final colonel of the regiment. Major F.M. Kent became lieutenant colonel and Company H Captain S.S. Batchelor became major. After supporting the army reserve artillery in the spring and summer of that year, the 1st Louisiana Regulars were temporarily consolidated with the 8th Arkansas Infantry to fight in the Battle of Chickamauga between 19 and 20 September.[1]

Due to further losses at Chickamauga, the regiment was assigned as army headquarters guard during the Chattanooga campaign, reduced to less than a hundred men. Continuing headquarters guard duty into the early spring of 1864 at Dalton, Georgia, the regiment joined Randall L. Gibson's Louisiana brigade in April. Kent died on 2 April and was replaced by Batchelor; Company I Captain Douglas West became major. It participated in the marches of the Atlanta campaign but saw little action until the 28 July Battle of Ezra Church. Among those killed at Ezra Church was Company G Captain William H. Sparks. After the fall of Atlanta, the regiment participated in the Franklin–Nashville Campaign, including the Battle of Nashville between 15 and 16 December.[1]

After the defeat of the army at Nashville, the regiment and its brigade were sent to Mobile in February 1865. There, the regiment was consolidated with the 16th and 20th Louisiana Infantry and the 4th Louisiana Battalion during the month to form a combined unit under 16th Louisiana Colonel Robert Lindsay that totalled 103 effectives.[61] The regiment fought at the Battle of Spanish Fort between 27 March and 8 April. After the evacuation from Mobile, they surrendered at Gainesville, Alabama on 12 May. During the war, the regiment's dead numbered 176 killed in action, 52 of disease, two by accident, one murdered, and two executed.[1]

References

Citations

- Bergeron 1996, pp. 69–71.

- Hearn 1995, pp. 10–12.

- Hearn 1995, pp. 18–19.

- Johansson 2011, pp. 87–88.

- "Departure of the First Company". Times-Picayune. 17 January 1861. p. 5 – via Newspapers.com.

- "The Southern Revolution". New Orleans Crescent. 11 January 1861. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Military Movements". Times-Picayune. January 12, 1861. p. 5 – via Newspapers.com.

- "The Military Excitement". Daily Delta. 11 January 1861. p. 7 – via Newspapers.com.

- Hearn 1995, pp. 13–16.

- "Annual Message of Thomas O. Moore to the General Assembly". Times-Picayune. 25 January 1861. p. 8 – via Newspapers.com.

- Bearss 1961c, p. 406.

- "Official Journal of the Convention of the State of Louisiana". New Orleans Crescent. 18 February 1861. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Military Appointments". New Orleans Crescent. 26 March 1861. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- Salling 2010, p. 158.

- Pierson 2008, pp. 79–82.

- "Return of Capt. Jaquess' Company". New Orleans Crescent. 19 March 1861. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Wants". Daily Delta. 9 April 1861. p. 7 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Military". New Orleans Crescent. 11 April 1861. p. 5 – via Newspapers.com.

- Hess 2016, pp. 15–19.

- Bearss 1961a, pp. 233, 241, 244.

- Hearn 1995, p. 28.

- Hearn 1995, pp. 28–29.

- "The Santa Rosa Affair". Times-Picayune. 23 October 1861. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- Bearss 1957, pp. 145–148.

- Bearss 1957, pp. 152–154.

- Official Records, Series I, Volume VI, p. 492.

- Bearss 1957, pp. 163–165.

- Official Records, Series I, Volume VI, pp. 494–495.

- Hess 2016, pp. 22–23.

- Bearss 1961b, pp. 333–335.

- Smith 2014, pp. 10–11.

- Hess 2016, pp. 28–29.

- Bearss 1961b, pp. 338–339.

- Official Records, Series I, Volume X, Book II, pp. 306–307.

- Official Records, Series I, Volume X, Book I, p. 14.

- Daniel 1997, p. 79.

- Smith 2014, p. 27.

- Smith 2014, pp. 15–16.

- Official Records, Series I, Volume X, Book I, p. 30.

- Official Records, Series I, Volume X, Book I, pp. 22–23.

- Smith 2014, pp. 50–51, 53, 56.

- Smith 2014, pp. 59, 64.

- Smith 2014, p. 430.

- Smith 2014, pp. 73, 87.

- Daniel 1997, pp. 154–155.

- Smith 2014, pp. 120–122.

- Official Records, Series I, Volume X, Book I, pp. 537–539.

- Smith 2014, pp. 124–128.

- Smith 2014, p. 142.

- Smith 2014, pp. 130–131.

- Official Records, Series I, Volume X, Book I, pp. 537–539, 542–543.

- Smith 2014, pp. 211, 215.

- Daniel 1997, pp. 253–254.

- Smith 2014, pp. 226, 229–231.

- Smith 2014, pp. 248, 253.

- Smith 2014, pp. 268–269, 350–351.

- Smith 2014, pp. 363, 379–381, 390, 392.

- Daniel 1997, p. 313.

- Official Records, Series I, Volume X, Book I, p. 789.

- Salling 2010, pp. 57–58.

- Salling 2010, p. 220.

Bibliography

- Bearss, Edwin S. (October 1957). "Civil War Operations in and around Pensacola". Florida Historical Quarterly. 36 (2): 125–165. ISSN 0015-4113. JSTOR 30139783.

- Bearss, Edwin S. (January 1961). "Civil War Operations in and around Pensacola Part II". Florida Historical Quarterly. 39 (3): 231–255. ISSN 0015-4113. JSTOR 30139856.

- Bearss, Edwin S. (April 1961). "Civil War Operations in and around Pensacola Part III". Florida Historical Quarterly. 39 (4): 330–353. ISSN 0015-4113. JSTOR 30154952.

- Bearss, Edwin S. (Autumn 1961). "The Seizure of the Forts and Public Property in Louisiana". Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association. 2 (4): 401–409. ISSN 0024-6816. JSTOR 4230634.

- Bergeron, Arthur W. (1996). Guide to Louisiana Confederate Military Units, 1861–1865. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0-8071-2102-9.

- Daniel, Larry J. (1997). Shiloh: The Battle That Changed the Civil War. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-80375-5.

- Hearn, Chester G. (1995). The Capture of New Orleans, 1862. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-3070-4.

- Hess, Earl J. (2016). Braxton Bragg: The Most Hated Man of the Confederacy. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-46962-875-2.

- Johansson, M. Jane (2011). "Daniel Weisiger Adams: Defender of the Confederacy's Heartland". In Hewitt, Lawrence Lee; Bergeron, Arthur W. (eds.). Confederate Generals in the Western Theater: Essays on America's Civil War. 3. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. pp. 87–120. ISBN 978-1-57233-790-9.

- Pierson, Michael D. (2008). Mutiny at Fort Jackson: The Untold Story of the Fall of New Orleans. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-3228-8.

- Salling, Stuart (2010). Louisianians in the Western Confederacy: The Adams-Gibson Brigade in the Civil War. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 9780786456833.

- Smith, Timothy B. (2014). Shiloh: Conquer or Perish. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-1995-5.

- The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. I (VI). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. 1882. OCLC 427057.

- The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. I (X): I. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. 1884. OCLC 427057.

- The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. I (X): II. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. 1884. OCLC 427057.