2012 (film)

2012 is a 2009 American science fiction disaster film directed by Roland Emmerich. It was produced by Harald Kloser, Mark Gordon, and Larry J. Franco, and written by Kloser and Emmerich. The film stars John Cusack, Chiwetel Ejiofor, Amanda Peet, Oliver Platt, Thandie Newton, Danny Glover, and Woody Harrelson. The plot follows geologist Adrian Helmsley (Ejiofor), who discovers the Earth's crust is becoming unstable after a massive solar flare caused by an alignment of the planets, and novelist Jackson Curtis (Cusack) as he attempts to bring his family to safety as the world is destroyed by a series of extreme natural disasters caused by this. The film refers to Mayanism and the 2012 phenomenon in its portrayal of cataclysmic events.

| 2012 | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Roland Emmerich |

| Produced by | |

| Written by |

|

| Story by |

|

| Starring | |

| Music by |

|

| Cinematography | Dean Semler |

| Edited by |

|

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 158 minutes |

| Country | United States[1] |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $200 million[2] |

| Box office | $791.2 million[3] |

Filming, originally planned for Los Angeles, began in Vancouver in August 2008.[4] After a lengthy advertising campaign which included the creation of a website from its main characters' point of view[5] and a viral marketing website on which filmgoers could register for a lottery number to save them from the ensuing disaster,[6] 2012 was released on November 13, 2009, to commercial success, grossing over $769 million worldwide against a production budget of $200 million, becoming the fifth highest-grossing film of 2009. The film received mixed reviews, with praise for its visual effects, but criticism of its screenplay and runtime.

Plot

In 2009, American geologist Adrian Helmsley visits astrophysicist Satnam Tsurutani in India and learns that an exotic new type of neutrinos from a huge solar flare are heating Earth's core. In Washington, D.C., Helmsley presents his information to White House Chief of Staff Carl Anheuser, who brings him to meet U.S. President Thomas Wilson.

In 2010, Wilson and other world leaders begin a secret project to ensure humanity's survival. China and the G8 nations begin building nine arks, each capable of carrying 100,000 people, in the Himalayas near Cho Ming, Tibet. Nima, a Buddhist monk, is evacuated and his brother Tenzin joins the ark project. Funding is raised by secretly selling tickets at €1 billion per person. By 2011, articles of value are moved to the arks with the help of art expert and First Daughter Laura Wilson.

In 2012, struggling Manhattan Beach, California-based science-fiction writer Jackson Curtis is a chauffeur for Russian billionaire Yuri Karpov. Jackson's former wife Kate and their children Noah and Lilly live with Kate's boyfriend, plastic surgeon and amateur pilot Gordon Silberman. Jackson takes Noah and Lilly camping in Yellowstone National Park. When they enter an area fenced off by the United States Army, they are caught and brought to Adrian, who has read Jackson's books. After being released they meet conspiracy theorist Charlie Frost, who hosts a radio show from the park.

That night, after the military evacuates Yellowstone, Jackson watches Charlie's video of Charles Hapgood's theory that polar shifts and the Mesoamerican Long Count calendar predict a 2012 phenomenon and the end of the world. Charlie reveals that anyone attempting to inform the public was or will be killed. After Jackson and his children return home, earthquakes begin in California. Jackson rents a private plane and rescues his family as the Earth-crust displacement begins, causing a 10.9 magnitude earthquake. Jackson and his family escape Los Angeles as much of the city collapses into the Pacific Ocean.

The group flies to Yellowstone to retrieve a map from Charlie with the arks' location. As they leave, the Yellowstone Caldera erupts; Charlie is killed while covering the eruption. The group lands in Las Vegas to find a larger plane and meet Yuri, his twin sons Alec and Oleg, his girlfriend Tamara and their pilot Sasha. Sasha and Gordon fly them out in an Antonov An-500 as the Yellowstone ash cloud envelops Las Vegas.

Adrian, Carl, and Laura fly to the arks on Air Force One. Wilson remains in Washington, D.C. to address the nation while millions of people die in earthquakes and megatsunamis worldwide, including himself. With the presidential line of succession broken, Carl assumes the position of acting commander-in-chief.

As Jackson's group reaches China, their plane runs out of fuel. Sasha continues flying the plane as the others escape in a Bentley Continental Flying Spur stored in the cargo hold. Sasha is killed when the plane slides off a cliff. The others are spotted by Chinese Air Force helicopters. Yuri and his sons, who have tickets, are taken to the arks leaving Tamara (who Yuri did not buy a ticket for as he suspected she was having an affair with Sasha), Gordon and the Curtis family. The remaining group is picked up by Nima and brought to the arks with his grandparents. With Tenzin's help, they stow away on Ark 4, where the U.S. contingent is located. As a megatsunami breaches the Himalayas and approaches the site, an impact driver lodges in the ark-door gears, keeping a boarding gate open, which prevents the ship's engines from starting. In the ensuing chaos, Gordon and Tamara are killed. Yuri is killed as well when saving his children. Tenzin is injured, the ark begins filling with water and is set adrift. Jackson and Noah dislodge the tool and the crew regains control of the Ark before it strikes Mount Everest. Jackson is reunited with his family and reconciles with Kate.

Twenty-seven days later, the waters are receding. The arks approach the Cape of Good Hope, where the Drakensberg mountains have now become the highest mountain range on Earth, due to the continent of Africa, plus a few areas of Europe and Asia, having risen above the waters. Adrian and Laura begin a relationship, while Jackson and Kate rekindle their romance.

Alternate ending

An alternate ending appears in the film's DVD release. After Captain Michaels (the Ark 4 captain) announces that they are heading for the Cape of Good Hope, Adrian learns by phone that his father, Harry, and Harry's friend Tony survived a megatsunami which capsized their cruise ship, the Genesis. Adrian and Laura strike up a friendship with the Curtises; Kate thanks Laura for taking care of Lily, Laura tells Jackson that she enjoyed his book Farewell Atlantis, and Jackson and Adrian have a conversation reflecting the events of the worldwide crisis. Jackson returns Noah's cell phone, which he recovered during the Ark 4 flood. The ark finds the shipwrecked Genesis and her survivors on a beach.[7][8]

Cast

.jpg.webp)

- John Cusack as Jackson Curtis, a struggling writer and a father of two children[9]

- Chiwetel Ejiofor as geologist Adrian Helmsley, chief science advisor to the U.S. President[10]

- Amanda Peet as Kate Curtis, a medical student and Jackson's former wife[11]

- Oliver Platt as Carl Anheuser, the White House Chief of Staff

- Thandie Newton as Laura Wilson, an art expert and First Daughter

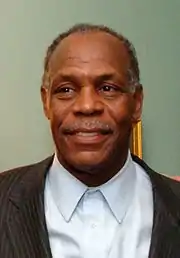

- Danny Glover as Thomas Wilson, the President of the United States and Laura's father.

- Woody Harrelson as Charlie Frost, a fringe science conspiracy theorist and radio talk-show host

- Liam James as Noah Curtis, Jackson and Kate's son

- Morgan Lily as Lilly Curtis, Jackson and Kate's daughter

- Tom McCarthy as Gordon Silberman, a plastic surgeon and Kate's boyfriend[12]

- Zlatko Burić as Yuri Karpov, a Russian billionaire and former boxer

- Beatrice Rosen as Tamara Jikan, Yuri's girlfriend

- Alexandre and Philippe Haussmann as Alec and Oleg Karpov, Yuri's twin sons

- Johann Urb as Sasha, Yuri's pilot

- John Billingsley as Frederick West, a colleague of Adrian

- Ryan McDonald as Scotty, Adrian and Frederick's assistant

- Jimi Mistry as Satnam Tsurutani, an Indian astrophysicist who discovers the neutrinos which are warming Earth's crust

- Agam Darshi as Aparna Tsurutani, Satnam's wife

- Chin Han as Tenzin, an ark worker who attempts to save his family

- Osric Chau as Nima, a Buddhist monk and Tenzin's brother

- Tseng Chang as Grandfather Sonam, their grandfather

- Lisa Lu as Grandmother Sonam, their grandmother

- Blu Mankuma as Harry Helmsley, Adrian's father and Tony Delgatto's vocal partner

- George Segal as Tony Delgatto, a jazz singer

- Stephen McHattie as Captain Michaels, captain of Ark 4

- Patrick Bauchau as Roland Picard, director of the Louvre, who is killed with a car bomb by the U.S. government

- Henry O as Lama Rinpoche, a Buddhist monk

- Karin Konoval as Sally, President Wilson's secretary

- Dean Marshall as the Ark 4 communications officer

- Zinaid Memisevic as Sergey Makarenko, the President of Russia

- Merrilyn Gann as the German Chancellor

- Lyndall Grant as the governor of California

- Vincent Cheng as a Chinese colonel

- Leonard Tenisci as the Italian Prime Minister

- Elizabeth Richard as Queen Elizabeth II

- Frank C. Turner as Preacher

Production

Development

Graham Hancock's Fingerprints of the Gods was listed in 2012's credits as the film's inspiration,[13] and Emmerich said in a Time Out interview: "I always wanted to do a biblical flood movie, but I never felt I had the hook. I first read about the Earth's Crust Displacement Theory in Graham Hancock's Fingerprints of the Gods."[14] He and composer-producer Harald Kloser worked closely together, co-writing a spec script (also titled 2012) which was marketed to studios in February 2008. A number of studios heard a budget projection and story plans from Emmerich and his representatives, a process repeated by the director after Independence Day (1996) and The Day After Tomorrow (2004).[15]

Later that month, Sony Pictures Entertainment received the rights to the spec script. Planned for distribution by Columbia Pictures,[16] 2012 cost less than its budget; according to Emmerich, the film was produced for about $200 million.[2]

Filming, originally scheduled to begin in Los Angeles in July 2008,[4] began in Kamloops, Savona, Cache Creek and Ashcroft, British Columbia.[17] With a Screen Actors Guild strike looming, the film's producers made a contingency plan to salvage it.[18] Uncharted Territory, Digital Domain, Double Negative, Scanline, and Sony Pictures Imageworks were hired to create 2012's computer-animated visual effects.

The film depicts the destruction of several cultural and historical icons around the world. Emmerich said that the Kaaba was considered for selection, but Kloser was concerned about a possible fatwā against him.[19][20]

Marketing

2012 was marketed by the fictional Institute for Human Continuity, featuring a book by Jackson Curtis (Farewell Atlantis),[5] streaming media, blog updates and radio broadcasts from zealot Charlie Frost on his website, This Is The End.[5] On November 12, 2008, the studio released the first trailer for 2012. With a tsunami surging over the Himalayas and a purportedly scientific message that the world would end in 2012, the trailer's message was that international governments were not preparing their populations for the event. The trailer ended with a suggestion to viewers to "find out the truth" by entering "2012" on a search engine. The Guardian called the film's marketing "deeply flawed", associating it with "websites that make even more spurious claims about 2012".[21]

The studio introduced a viral marketing website operated by the Institute for Human Continuity, where filmgoers could register for a lottery number to be part of a small population which would be rescued from the global destruction.[6] David Morrison of NASA, who received over 1,000 inquiries from people who thought the website was genuine, condemned it. "I've even had cases of teenagers writing to me saying they are contemplating suicide because they don't want to see the world end", Morrison said. "I think when you lie on the internet and scare children to make a buck, that is ethically wrong."[22] Another marketing website promoted Farewell Atlantis, a fictional novel about the events of 2012.[5]

Comcast organized a "roadblock campaign" to promote the film in which a two-minute scene was broadcast on 450 American commercial television networks, local English-language and Spanish-language stations, and 89 cable outlets during a ten-minute window between 10:50 and 11:00 pm Eastern and Pacific Time on October 1, 2009.[23] The scene featured the destruction of Los Angeles and ended with a cliffhanger, with the entire 5:38 clip available on Comcast's Fancast website. According to Variety, "The stunt will put the footage in front of 90% of all households watching ad-supported TV, or nearly 110 million viewers. When combined with online and mobile streams, that could increase to more than 140 million".[23]

Soundtrack

| 2012: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by | |

| Released | November 10, 2009 |

| Length | 57:48 |

| Label | RCA Victor |

| Singles from 2012: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack | |

| |

The film's score was composed by Harald Kloser and Thomas Wander. Singer Adam Lambert contributed a song to the film, "Time for Miracles", and expressed his gratitude in an MTV interview.[24] The 24-song soundtrack includes "Fades Like a Photograph" by Filter and "It Ain't the End of the World" by George Segal and Blu Mankuma.[25] The trailer track was "Master of Shadows" by Two Steps From Hell.

Release

2012 was released to cinemas on November 13, 2009, in Sweden, Canada, Denmark, Mexico, India, the United States, and Japan.[26] According to the studio, the film could have been completed for a summer release but the delay allowed more time for production.

The DVD and Blu-ray versions were released on March 2, 2010. The two-disc Blu-ray edition includes over 90 minutes of features, including Adam Lambert's music video for "Time for Miracles" and a digital copy for PSP, PC, Mac, and iPod.[27] A 3D version was released in Cinemex theaters in Mexico in February 2010.[28] A 4K Ultra HD Blu-ray was released on January 19, 2021.[29]

Reception

Box office

2012 grossed $166.1 million in North America and $603.5 million in other territories for a worldwide total of $769.6 million against a production budget of $200 million,[3] making it the first film to gross over $700 million worldwide without crossing $200 million domestically.[30] Worldwide, it was the fifth-highest-grossing 2009 film[31] and the fifth-highest-grossing film distributed by Sony-Columbia, (behind Sam Raimi's Spider-Man trilogy and Skyfall).[32] 2012 is the second-highest-grossing film directed by Roland Emmerich, behind Independence Day (1996).[33] It earned $230.5 million on its worldwide opening weekend, the fourth-largest opening of 2009 and for Sony-Columbia.[34]

2012 ranked number one on its opening weekend, grossing $65,237,614 on its first weekend (the fourth-largest opening for a disaster film).[35] Outside North America it is the 28th-highest-grossing film, the fourth-highest-grossing 2009 film,[36] and the second-highest-grossing film distributed by Sony-Columbia, after Skyfall. 2012 earned $165.2 million on its opening weekend, the 20th-largest overseas opening.[37] Its largest opening was in France and the Maghreb ($18.0 million). In total earnings, the film's three highest-grossing territories after North America were China ($68.7 million), France and the Maghreb ($44.0 million), and Japan ($42.6 million).[38]

In 2020, the film received renewed interest during the COVID-19 pandemic, becoming the second-most popular film and seventh-most popular overall title on Netflix in March 2020.[39]

Critical response

On Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an approval rating of 39% based on 243 reviews and an average rating of 5.02/10. The site's critical consensus reads, "Roland Emmerich's 2012 provides plenty of visual thrills, but lacks a strong enough script to support its massive scope and inflated length."[40] On Metacritic, the film has a score of 49 out of 100 based on 34 critics, indicating "mixed or average reviews".[41] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "B+" on an A+ to F scale.[42]

Roger Ebert praised 2012, giving it 3 1⁄2 stars out of 4 and saying that it "delivers what it promises and since no sentient being will buy a ticket expecting anything else, it will be, for its audiences, one of the most satisfactory films of the year".[43] Ebert and Claudia Puig of USA Today called the film the "mother of all disaster movies".[43][44] But Peter Travers of Rolling Stone compared it to Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen: "Beware 2012, which works the dubious miracle of almost matching Transformers 2 for sheer, cynical, mind-numbing, time-wasting, money-draining, soul-sucking stupidity."[45]

Accolades

| Award | Category | Nominee(s) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Broadcast Film Critics Association Awards[47] | Best Visual Effects | Volker Engel, Marc Weigert, Mike Vézina | Nominated |

| NAACP Image Award[46] | Outstanding Supporting Actor in a Motion Picture | Chiwetel Ejiofor | Nominated |

| Danny Glover | Nominated | ||

| Motion Picture Sound Editors[48] | Best Sound Editing – Music in a Feature Film | Fernand Bos, Ronald J. Webb | Nominated |

| Best Sound Editing – Sound Effects and Foley in a Feature Film | Fernand Bos, Ronald J. Webb | Nominated | |

| Satellite Awards[49] | Best Sound (Editing and Mixing) | Paul N.J. Ottosson, Michael McGee, Rick Kline, Jeffrey J. Haboush, Michael Keller | Won |

| Best Visual Effects | Volker Engel, Marc Weigert, Mike Vézina | Won | |

| Best Art Direction and Production Design | Barry Chusid, Elizabeth Wilcox | Nominated | |

| Best Film Editing | David Brenner, Peter S. Elliot | Nominated | |

| Saturn Awards[50] | Saturn Award for Best Action, Adventure, or Thriller Film | 2012 | Nominated |

| Best Special Effects | Volker Engel, Marc Weigert, Mike Vézina | Nominated | |

| Visual Effects Society Awards[51] | Outstanding Visual Effects in a Visual Effects-Driven Feature Motion Picture | Volker Engel, Marc Weigert, Josh Jaggars | Nominated |

| Best Single Visual Effect of the Year | Volker Engel, Marc Weigert, Josh R. Jaggars, Mohen Leo for "Escape from L.A." | Nominated | |

| Outstanding Created Environment in a Feature Motion Picture | Haarm-Pieter Duiker, Marten Larsson, Ryo Sakaguchi, Hanzhi Tang for "Los Angeles Destruction" | Nominated |

North Korean ban

North Korea reportedly banned the possession or viewing of 2012. The year was the 100th anniversary of the birth of the nation's founder, Kim Il-sung, and was designated as "the year for opening the grand gates to becoming a rising superpower"; a film depicting the year negatively was deemed offensive by the North Korean government. Several people in North Korea were reportedly arrested for possessing (or viewing) imported copies of 2012 and charged with "grave provocation against the development of the state".[52][53]

Canceled television spin-off

In 2010 Entertainment Weekly reported a planned spin-off television series, 2013, which would have been a sequel to the film.[54] 2012 executive producer Mark Gordon told the magazine, "ABC will have an opening in their disaster-related programming after Lost ends, so people would be interested in this topic on a weekly basis. There's hope for the world despite the magnitude of the 2012 disaster as seen in the film. After the movie, there are some people who survive, and the question is how will these survivors build a new world and what will it look like. That might make an interesting TV series."[54] However, plans were later canceled for budgetary reasons.[54] It would have been Emmerich's third film to spawn a spin-off; the first was Stargate (followed by Stargate SG-1, Stargate Infinity, Stargate Atlantis, Stargate Universe), and the second was Godzilla (followed by the animated Godzilla: The Series).

References

- "2012". American Film Institute. Retrieved May 6, 2014.

- Blair, Ian (November 6, 2013). "'2012's Roland Emmerich: Grilled". The Wrap. Archived from the original on November 14, 2009. Retrieved December 9, 2012.

- "2012 (2009)". Box Office Mojo. IMDb. Archived from the original on August 20, 2011. Retrieved August 2, 2016.

- Siegel, Tatiana (May 19, 2014). "John Cusack set for 2012". Variety. Archived from the original on July 9, 2008. Retrieved July 14, 2014.

- "Farewell Atlantis by Jackson Curtis – Fake website". Sony Pictures. Archived from the original on July 10, 2011. Retrieved June 30, 2013.

- Billington, Alex (November 15, 2012). "Roland Emmerich's 2012 Viral — Institute for Human Continuity". FirstShowing.net. Archived from the original on December 20, 2008. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- B. Alan Orange. "EXCLUSIVE VIDEO: Watch the Alternate Ending for '2012'!". MovieWeb.

- "Roland Emmerich Talks 2012 Blu-ray Alternate Ending". Blu-ray.com.

- Foy, Scott (October 2, 2009). "Five Hilariously Disaster-ffic Minutes of 2012". Dread Central. Retrieved June 30, 2011.

- Simmons, Leslie (May 19, 2008). "John Cusack ponders disaster flick". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on May 25, 2008. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- Simmons, Leslie; Kit, Borys (June 13, 2008). "Amanda Peet is 2012 lead". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on July 5, 2008. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- Kit, Borys (July 1, 2008). "Thomas McCarthy joins 2012". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on July 3, 2008. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- "2012 (2015) – Credit List" (PDF). chicagoscifi.com. Retrieved November 25, 2014.

- Jenkins, David (November 16, 2009). "Roland Emmerich's guide to disaster movies". Time Out. Archived from the original on November 16, 2009. Retrieved November 25, 2009. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Fleming, Michael (February 19, 2014). "Studios vie for Emmerich's 2012". Variety. Retrieved July 14, 2014.

- Fleming, Michael (February 21, 2014). "Sony buys Emmerich's 2012". Variety. Retrieved July 14, 2014.

- "2012 Filmed in Thompson Region!". Tourismkamloops.com. December 14, 2012. Archived from the original on July 17, 2011. Retrieved June 30, 2012.

- "Big Hollywood films shooting despite strike threat". Reuters. August 1, 2008. Retrieved August 5, 2008.

- Ben Child (October 3, 2015). "Emmerich reveals fear of fatwa axed 2012 scene". The Guardian. London.

- Jonathan Crow (October 3, 2015). "The One Place on Earth Not Destroyed in '2012'". Yahoo! Movies.

- Pickard, Anna (November 25, 2014). "2012: a cautionary tale about marketing". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on January 22, 2009. Retrieved December 10, 2008.

- Connor, Steve (October 17, 2015). "Relax, the end isn't nigh". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on October 20, 2009. Retrieved October 20, 2015.

- Graser, Mark (September 23, 2009). "Sony readies 'roadblock' for 2012". Variety. Archived from the original on October 11, 2009. Retrieved September 29, 2015.

- Vena, Jocelyn (November 4, 2009). "Adam Lambert Feels 'Honored' To Be On '2012' Soundtrack". MTV Movie News. Archived from the original on January 28, 2010. Retrieved January 18, 2010.

- "2012: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack". Amazon.com. Retrieved April 3, 2011.

- "2012 Worldwide Release Dates". sonypictures.com. Archived from the original on February 9, 2010. Retrieved November 12, 2009.

- "Early Art and Specs: 2012 Rocking on to DVD and Blu-ray". DreadCentral. Retrieved July 3, 2010.

- "Cinemex". cinemex.com. Archived from the original on February 8, 2013.

- "2012". January 19, 2021. Retrieved November 27, 2020 – via Amazon.

- Scott Mendelson (June 12, 2017). "Box Office: Johnny Depp's 'Pirates 5' Breaks Walt Disney's Memorial Day Curse". Forbes. Retrieved June 12, 2017.

- "2009 Worldwide Grosses". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on January 21, 2010. Retrieved January 20, 2015.

- "All Time Worldwide Box Office Grosses". boxofficemojo.com.

- "Roland Emmerich". boxofficemojo.com.

- "All Time Worldwide Opening Records at the Box Office". boxofficemojo.com.

- "Disaster Movies at the Box Office". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved December 25, 2014.

- "Overseas Total Yearly Box Office". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved June 29, 2011.

- "Overseas Total All Time Openings". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 23, 2011. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- "2012 (2009) - International Box Office Results - Box Office Mojo". Box Office Mojo. 2010. Retrieved July 7, 2017.

- Clark, Travis (March 20, 2020). "Movies and TV shows about pandemics and disasters are surging in popularity on Netflix". Business Insider. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- "2012 (2009)". Rotten Tomatoes.

- "2012 Reviews". Metacritic.

- Finke, Nikki (November 15, 2009). "'2012' Dominates For $225M 5-Day Launch Worldwide; 'Xmas Carol' Holds Well; 'Precious' & 'Fantastic Mr. Fox' Play To Packed Theaters; 'Pirate Radio' Sinks". Deadline.

Despite dismal reviews, the film received an “A” Cinemascore for moviegoers under 18 and a “B+” overall.

- Ebert, Roger (November 12, 2009). "The late, great planet Earth: A thoroughly destroyable show". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on November 15, 2009. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- Puig, Claudia (November 13, 2009). "'2012': Now that's Armageddon!". USA Today. Retrieved November 20, 2009.

- Travers, Peter (November 12, 2009). "2012: Review". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on November 15, 2009. Retrieved November 12, 2009.

- "The 41st NAACP Image Awards". NAACP Image Award. Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved June 30, 2011.

- "The 15th Annual Critics Choice Movie Awards". Broadcast Film Critics Association Awards. Archived from the original on July 19, 2012. Retrieved June 30, 2011.

- "2010 Golden Reel Award Nominees: Feature Films". Motion Picture Sound Editors. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved June 30, 2011.

- "Satellite Awards Announce 2009 Nominations". Filmmisery.com. November 29, 2009. Retrieved June 30, 2011.

- Miller, Ross (February 19, 2010). "Avatar Leads 2010 Saturn Awards Nominations". Screenrant.com. Archived from the original on July 3, 2011. Retrieved June 30, 2011.

- "8th Annual VES Awards". visual effects society. Retrieved December 22, 2017.

- Nishimura, Daisuke (March 26, 2010). "Watching '2012' a no-no in N. Korea". Asahi.com. The Asahi Shimbun Company. Archived from the original on March 29, 2010. Retrieved April 25, 2010.

- "North Korea fears 2012 disaster film will thwart rise as superpower". The Telegraph. March 26, 2010. Retrieved July 18, 2011.

- Rice, Lynette (March 2, 2010). "ABC passes on '2012' TV show". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on October 17, 2010. Retrieved July 3, 2014.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: 2012 (film) |

- Official website

- 2012 at IMDb

- 2012 at AllMovie

- 2012 at the TCM Movie Database

- 2012 at the American Film Institute Catalog

- 2012 at Rotten Tomatoes

- 2012 at Metacritic

- 2012 at Box Office Mojo