ACL injuries in the Australian Football League

In the Australian Football League (AFL) injuries are now very common and consistent due to the game been a contact sport. The Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) knee injury is one of the three major and common injuries that occur in the AFL. The ACL injury has long-term effects on the player, not only in physical activity but also in their own daily lives in the future. Studies have attempted to understand and work out a prevention for ACL injuries but it is too complicated.[1] Once a player has injured their ACL, there is a very high possibility that the injury can occur again to the same knee. There is even the chance of the opposite knee been injured due to the fact the player protecting the reconstructed knee.[2]

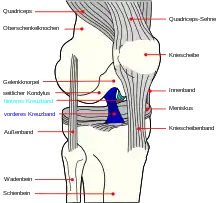

Structure of the Knee and the ACL

An ACL rupture is the most common injury that takes place in the knee. The ACL is very small, smaller than some might think; the average length is 38mm and only 11mm wide. The knee is formed by the connection of the femur (upper leg bone) and the Tibia (lower leg bone) with another two bones been the fibula (small bone next to the tibia) and the patella (the knee cap). Within these two main bones tendons attach the bones to the muscles that give the knee movement, while the ligaments provide the knee with stability. The ACL looks like a mixture of an oval and triangle shape, and is located in a very compact area within the knee. The ACL fibers are in place to give direction for the knee to move, such as a kicking or twisting motion. If an ACL rupture occurs, it immediately forces an increase for not only the anterior tibial translation but also the internal tibial rotation as the femur is pushed back to rotate, this creates trauma to the knee as it is not stabilised. The ACL is there to create rotational stability within the knee to be able to produce different motions. Importantly the ACL restraints the anterior tibial translation, providing 85-87% total retraining force.[3]

Cause of injury

AFL is said to be a contact sport, which it is, but not every Anterior cruciate ligament injury occurs due to contact. Studies show that out of 34 ACL injuries assessed, 56% of injuries were due to no contact situations. These studies showed that ACL injuries occur most of the time due to type of movement, change of direction resulting in the knee to give way, speed of player, angle of the knee when landing and the lack of stability the player has.[4] All AFL footballers wear boots with studs at the bottom of them; this creates grip and friction with the player and the surface. Although boots help the player play football, it creates an increase in risk of injury to the ACL.[5]

Angle of the Knee

The process of an ACL injury where no contact from a player is applied is mostly due to the player landing on the surface after going up for a mark. Dependent on the hardness of the surface or the quality of the grass and how well the player lands will impact on the injury.[6]

Lack of Stability

Lack of stability in the knee is a main cause of rupturing the ACL in the knee. Most advanced athletes struggle to gain enough stability within the knee while exercising causing the possibility of injury. The ACL exists to provide the knee stability but it is the athletes duty to make sure the knee is stable enough to be able to play out the game.[7]

Prevention

The risk of injuring the ACL is very high for an athlete, as most professionals say it is worrying how common the injury is becoming. As there is no real way to stop an ACL injury from occurring, there can be ways to lower the risk. Once an athlete does an ACL injury it is extremely difficult to be able to come back to football, it even creates a higher risk of a second ACL injury after having the first reconstructed. This is why it is vitally important for an AFL player to build strong muscles and bones to benefit them in their career.[8] Small doses of training can help prevent ACL injuries, as athletes will not over train leaving their body fatigued and sore. The small doses of training only have to include, strength, balance, plyo- metric or agility to gain some prevention from the injury.[9] It is also important to talk to the coach or training staff to inform them of what you can and cannot do. Some things in life are preventable, but injuries such as ACL injuries are just too hard to prevent.

Recovery

After an injury it is important that the player recovers properly. Recovery includes resting, low activity, the correct diet, strength and training. Balance was found to be a useful way of preventing ACL injuries as it builds strength within the knee. Improving balance is one of the first ways to recover after an ACL injury, studies have also found a series of jumping, landing, posture and change of direction to also help strengthen the knee.[2] Balance is the ability to maintain the centre of mass of a body within the base of support. The two types of balance are, static and dynamic. Static been the ability to control your body when in a stationary position, while dynamic been the ability to have control of the body when moving. When trying to understand balance it is important to acknowledge three factors which are; mass, the area of the bass of support and position to the centre of gravity. Balance evolves around the base of support as well as the centre of gravity.[10] For the injured footballer to obtain maximal benefits from this training then they will need to work on their balance consistently to build strength within both knees and around their whole body.[2]

References

- Hong, Y. (2012). ACL injury: Incidences, healing, rehabilitation, and prevention: Part of the routledge olympic special issue collection. Research in Sports Medicine, 20(3), 155. doi:10.1080/15438627.2012.682526

- Hrysomallis, C. (2013). Injury incidence, risk factors and prevention in Australian rules football. Sports Medicine, 43(5), 339-354. doi:10.1007/s40279-013-0034-0

- Noyes, F. R., & Barber-Westin, S. (2012). ACL injuries in the female athlete: Causes, impacts, and conditioning programs (1. Aufl.; 1 ed.). Dordrecht: Springer-Verlag.

- Cochrane, J. L., Lloyd, D. G., Buttfield, A., Seward, H., & McGivern, J. (2007). Characteristics of anterior cruciate ligament injuries in Australian football. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 10(2), 96-104. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2006.05.015

- Renstorm, P., Ljungqvist, A., Arendt, E., Beynnon, B., Fukubayashi, T., Garrett, W., Georgoulis, T., Hewett, T. E., Johnson, R., Krosshaug, T., Mandelbaum, B., Micheli, L., Myklebust, G., Roos, E., Roos, H., Schamash, P., Shultz, S., Werner, S., Wojtys, E., & Engebretsen, L. (2008). Non-contact ACL injuries in female athletes: An international olympic committee current concepts statement. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 42(6), 394-412. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2008.048934

- Smeathers, J., Urry, S., Butler, A., Nichols, C., Wearing, S., & Hooper, S. (2010). Non-contact ACL injuries: Association with clegg soil impact test values for sports fields, soil moisture and prevailing weather. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 12, e9-e10. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2009.10.020

- Chmielewski, T. L., Rudolph, K. S., & Snyder-Mackler, L. (2002). Development of dynamic knee stability after acute ACL injury. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology, 12(4), 267-274. doi:10.1016/S1050-6411(02)00013-5

- Ostojic, S., & Stojanovic, M. (2012). Preventing ACL injuries in team-sport athletes: A systematic review of training interventions. Research in Sports Medicine, 20(3), 223. doi:10.1080/15438627.2012.680988

- Myklebust, G., & Steffen, K. (2009). Prevention of ACL injuries: How, when and who? Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy : Official Journal of the ESSKA, 17(8), 857-858. doi:10.1007/s00167-009-0826-9

- Whipp, P.R., Elliott, B., Guelfi, K., Dimmock, J., Lay, B, Landers, G, & Alderson, J. (2010). Physical education studies 2A-2B: A textbook for teachers and students. Perth, WA: UWA Publishing.