Aaron ben Moses ben Asher

Aaron ben Moses ben Asher (Hebrew: אהרן בן משה בן אשר; Tiberian Hebrew: ʾAhărôn ben Mōšeh benʾĀšēr; 10th century, died c.960) was a Jewish scribe who lived in Tiberias in northern Israel and refined the Tiberian system of writing vowel sounds in Hebrew, which is still in use today, and serves as the basis for grammatical analysis.

Background

For over a thousand years ben Asher has been regarded by Jews of all streams as having produced the most accurate version of the Masoretic Text. Since his day, both handwritten manuscripts of the Tanakh and printed versions strove to follow his system and continue to do so. He lived and worked in the city of Tiberias on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee.

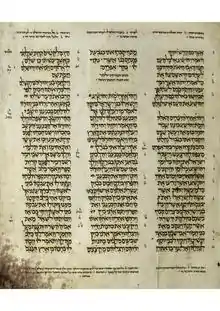

Ben Asher was descended from a long line of Masoretes, starting with someone called Asher, but nothing is known about them other than their names. His father, Moses ben Asher, is credited with writing the Cairo Codex of the Prophets (895 CE). If authentic, it is among the oldest manuscripts containing a large proportion of the Hebrew Bible. Umberto Cassuto used this manuscript as the basis of his edition of the Hebrew Bible. Aaron ben Asher himself added vowelization and cantillation notes, and mesorah to the Aleppo Codex, correcting its letter-text according to the masorah.

Maimonides accepted the views of ben Asher only in regard to open and closed sections, but apparently admired his work generally and helped to establish and spread his authority. Referring to a Bible manuscript then in Egypt, Maimonides wrote: "All relied on it, since it was corrected by ben Asher and was worked on and analyzed by him for many years, and was proofread many times in accordance with the masorah, and I based myself on this manuscript in the Sefer Torah that I wrote".

First serious scribe

Aaron ben Moses ben Asher was the first to take Hebrew grammar seriously. He was the first systematic Hebrew grammarian. His Sefer Dikdukei ha-Te'amim (Grammar or Analysis of the Accents) was an original collection of grammatical rules and masoretic information. Grammatical principles were not at that time considered worthy of independent study. The value of this work is that the grammatical rules presented by ben Asher reveal the linguistic background of vocalization for the first time. He had a tremendous influence on subsequent Biblical grammar and scholarship.

A rival system of note was that developed by the school of ben Naphtali.

Was ben Asher a Karaite?

There is a debate among scholars as to whether Aaron ben Asher was a Karaite. Documents found in the Cairo Geniza may suggest that ben Asher was a Karaite. One of the strongest arguments against this view is that it would be astonishing if Maimonides, famously opposed to the Karaites, had followed the authority of a Karaite, even in the matter of open and closed sections.

In his critiques of Karaites, Saadia Gaon mentioned a "ben Asher." Until recently, it never occurred to scholars to associate this "ben Asher" with the famous Aaron ben Asher of Tiberias. Recent research indicates, however, that it is possible. This may explain why he preferred the "ben Naphtali" system.

If Aaron ben Asher was indeed a Karaite, it may be argued that he was the most influential Karaite of all time.

References

Further reading

- Aaron Dotan, "Was Aharon Ben Asher Indeed a Karaite?" (Hebrew), in S.Z. Leiman, The Canon and Masorah of the Hebrew Bible: An Introductory Reader (New York: Ktav, 1974).

- Aaron Dotan, "Ben Asher's Creed" (Missoula, Montana: Scholars Press, 1977).

- Rafael Zer, "Was the Masorete of the Keter a Rabbanite or Karaite?", Sefunot 23 (2003) Pages 573-587 (Hebrew)