Abel Clarin de la Rive

Abel Clarin de la Rive (pseudonym of Pierre Abel Clarin Vivant,[1][2] Chalon-sur-Saône, France, 1855 – Chalon-sur-Saône 1914) was a French historian, essayist, journalist, and anti-Masonic writer.

Biography

Early years

Pierre Abel Clarin Vivant was born in 1855 in Chalon-sur-Saône in a Catholic family. He attended a high school of the Dominican Order and, despite his young age, participated in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 after joining the Army of the East of general Charles-Denis Bourbaki.[2] After the war, he continued his military career in French Algeria, where he developed an interest in Islam; some even believed he had become a Muslim, although he denied it.[3] Reportedly, his knowledge of Islam caught the attention of the French secret services, who asked him to travel throughout North Africa, dressed as a native and using the pseudonym of Shaykh Sihabil Klarin M’ta El Chott, and report to them.[4]

He left the Army in 1873 and started a career as a journalist, working for the Courrier de la Saône-et-Loire, La Belgique, La Côte d’Or, La Gazette du Centre et Le Franc-Bourguignon, writing among others articles on the history of Burgundy.[2] On the latter subject, he published, in 1881 and 1885, two volumes of a Histoire épisodique de Bourgogne (Episodical History of Burgundy) that he never completed.[1] In 1881, he had already published a novel, Une date fatale (A Fatal Date), where he criticized Spiritualism from a Catholic point of view.[2] His second novel, Ourida, was published in 1890 under his old military pseudonym of Shaykh Sihabil Klarin M’ta El Chott and, although he declared to write as a Catholic, introduced several occult themes.[4] In 1883, he had used information he collected while working for the Army to publish a Histoire générale de la Tunisie, depuis l’an 1590 avant Jésus-Christ jusqu’en 1883 (General History of Tunisia from 1590 BCE to 1883).[1]

Involvement in the Taxil hoax

From 1893 on, under the pseudonym of Abel Clarin de la Rive, Vivant emerged as a Catholic journalist and crusader against Freemasonry, writing for the national Catholic newspaper La Croix and for the specialized anti-Masonic magazine La Franc-Maçonnerie demasquée (Freemasonry Unmasked), founded by the French Catholic bishop Amand-Joseph Fava.[5]

Clarin became a friend of Léo Taxil and one of the many victims of the Taxil hoax. A former Freemason who claimed in 1885 to have converted to Catholicism, Taxil revealed in his books and articles that Freemasonry was secretly controlled by Satanists known as Palladists, and that two high priestesses called Diana Vaughan and Sophia Walder were competing for the leadership of Palladism. Later, Taxil claimed that Diana Vaughan had converted to Catholicism and had started publishing anti-Masonic books and tracts, in fact written by Taxil himself.[6] Many Catholics believed in the Taxil hoax, although some anti-Masonic writers didn’t, and repeatedly asked Taxil to introduce the elusive Diana Vaughan to the public. He promised to do so in a lecture in Paris scheduled for April 19, 1897, where instead he announced that his revelations were a hoax created to show to the world how gullible Catholics hostile to Freemasonry were.[6]

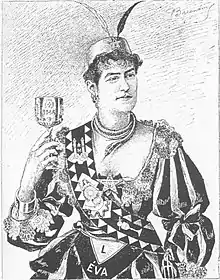

Clarin de la Rive was among those who believed in Taxil without reservations, and Taxil authorized him to publish in his book La Femme et l’enfant dans la franc-maçonnerie universelle (Women and children in universal Freemasonry), published in 1894, a "genuine portrait" of Sophia Walder, a character not less fictitious than Diana Vaughan. She appeared as masculine, as Taxil had claimed she was a lesbian and so commanded the stereotypes of that time.[6] The book is largely based on Taxil’s spurious revelations, but Clarin had studied sex magic before meeting Taxil and added his own speculations on sexual rituals allegedly practiced by the Palladists.[2]

While Taxil was cautious in connecting Palladism and Freemasonry with the Jews, and campaigned in the 1890 Paris municipal elections against the antisemitic leader, Édouard Drumont, Clarin de la Rive claimed in his 1895 book Le Juif et la franc-maçonnerie (Jews and Freemasonry) that both Palladism and Freemasonry were secretly controlled by Jews, and that Palladism was based on the Jewish Kabbalah.[2]

Antisemitic and political activism

After Taxil’s 1897 confession, Clarin de la Rive, who since 1896 was the editor of the magazine La France chrétienne (Christian France), a position in which he succeeded Taxil, was among the few anti-Masonic activists who maintained that Palladism and Diana Vaughan really existed (although Diana may have been killed by Taxil or his Masonic friends), and that the real hoax was the public confession of 1897.[6][5] However, because of the Taxil scandal, Clarin’s La France chrétienne lost a significant number of readers, and was at risk of bankruptcy, from which, according to French scholar Emmanuel Kreis, it was saved by the Dreyfus affair, which fueled French antisemitism.[2] The magazine acquired a new collaborator, Paul Antonini (1851-1900), and devoted a large part of its pages to antisemitic propaganda, insisting that the Jews were secretly organizing Freemasonry and Palladism.[1]

Kreis suggested that Antonini’s extreme conspiracy theories were perhaps not unrelated with his mental problems, which led him to a premature death in a psychiatric hospital in 1900.[2] Clarin de la Rive, however, continued the publication of La France chrétienne and in the same year 1900 was able to convert it from a bi-monthly to a weekly, which in 1910 changed its name into La France chrétienne antimaçonnique (Anti-Masonic Christian France), and in 1911 into La France antimaçonnique (Anti-Masonic France).[5]

Although personally a monarchist, in 1900 Clarin de la Rive campaigned for the republican nationalist League of Patriots and its leader Paul Déroulède in the Paris municipal elections, as he saw them as an obstacle to the political influence of Freemasonry.[2] The nationalist did win these elections, but Clarin believed that they did not pursue an effective anti-Masonic action, and founded an Union des patriotes catholiques (Union of Catholic Patriots) to support Catholic conservative candidates in the 1902 French legislative election.[5] The enterprise was largely unsuccessful, and Clarin de la Rive abandoned all hopes in electoral politics; in his last years, he criticized openly the position of Pope Leo XIII who had asked French Catholics to accept the republican regime, and from 1911 on, openly campaigned for a return to the monarchy.[2]

Clarin as opponent of the Theosophical Society and friend of René Guénon

In 1902, Clarin de la Rive founded a Conseil antimaçonnique de France (French Anti-Masonic Council), whose main activities was to sponsor Clarin’s lecture tours throughout France and an Anti-Masonic Museum in Paris.[5] In the first decade of the 20th century, while maintaining an antisemitic orientation, La France chrétienne devoted more and more attention to exposing the Theosophical Society, Martinism, Spiritualism, and Christian Science as dangerous cults more or less controlled by Jews and Freemasons.[2]

On the other hand, Clarin de la Rive was a firm believer in the supernatural, and befriended some members of the esoteric milieu, including René Guénon: the two men shared an interest in Islam, and from 1909 Guénon published several articles in Clarin’s magazine under the pseudonym of "Sphinx".[4] Guénon used La France chrétienne (later called La France antimaçonnique) to criticize monsignor Ernest Jouin and his magazine Revue internationale des sociétés secrètes, who in turn denounced Guénon’s brand of esotericism as anti-Christian.[2]

In 1911, Clarin de la Rive reported that, while a Catholic missionary was helping him translate a Hindu mantra in the offices of La France antimaçonnique, a Hindu holy man who introduced himself as Swami Narad Mani appeared im front of them "as a ghost from the astral world," claimed to be the head of a "European Observatory of True Truth Somaj," and gave to them a book, The Baptism of Light, where he exposed the "false" Theosophy of the Theosophical Society as opposed to the "genuine" Hindu Theosophy.[4] While some scholars believe that the Swami Narad Mani who wrote The Baptism of Light, which La France antimaçonnique duly published, was in fact the Indian opponent of the Theosophical Society, Hiran Singh, Kreis and fellow French scholar Michel Jarrige believe the story to be entirely fictitious and concluded that The Baptism of Light had been written by Guénon and Clarin de la Rive.[2][5]

Clarin de la Rive’s death was announced by La France antimaçonnique on July 16, 1914, with the indication that Guénon will become the new editor after the summer holidays; however, World War I prevented further publication of the magazine, whose last number was published on July 30, 1914.[2]

Influence in the United States

Clarin de la Rive is known in the United States because, together with Taxil, he denounced Albert Pike, who had become the Sovereign Grand Commander of the Scottish Rite's Southern Jurisdiction of the US in 1859, which is an appendant body of Freemasonry, as the alleged main leader of Satanic Palladism and a practitioner of sex magic.[2]

Clarin’s published works have been quoted and used by several conspiracy theorists, antisemitic and anti-Masonic writers in the US and the United Kingdom, such as Edith Starr Miller and William Guy Carr.[7][8][9][10]

Books by Abel Clarin de la Rive

- Histoire épisodique de Bourgogne (Episodical History of Burgundy), 2 vol., Dijon: J. Marchand, 1881 and 1885.

- Une Date fatale (A Fatal Date), Paris: C. Marpon and E. Flammarion, 1881.

- Histoire générale de la Tunisie, depuis l’an 1590 avant Jésus-Christ jusqu’en 1883 (General History of Tunisia from 1590 BCE to 1883), Tunis: E. Demoflys, 1883.

- Dupleix, ou les Français aux Indes Orientales (Dupleix, or the French in the West Indies), Lille: Desclée de Brouwer, 1888.

- Il Condottiere Giuseppe Garibaldi, 1870-1871 (The Condottiere Giuseppe Garibaldi, 1870-1871), Paris: A. Savine, 1892.

- La Femme et l’enfant dans la franc-maçonnerie universelle (Woman and Child in Universal Freemasonry), Paris: Delhomme et Briguet, 1894.

- Le Juif dans la franc-maçonnerie (Jews and Freemasonry). Paris: A. Pierre, 1895.

And, under the pseudonym of Shaykh Sihabil Klarin M’ta El Chott:

- Vocabulaire de la langue parlée dans les pays barbaresques (Vocabulary of the Language Spoken in the Barbary Countries), Paris and Limoges: H. Charles Lavauzelle, 1890.

- Ourida, Paris and Limoges: H. Charles Lavauzelle, 1890.

References

- James, Marie-France (1981). Esotérisme, occultisme, franc-maçonnerie et christianisme aux XIXe et XXe siècles : explorations bio-bibliographiques. Paris: Nouvelles Éditions Latines. p. 73. ISBN 978-2723301503.

- Kreis, Emmanuel (2017). Quis Ut Deus?: Antijudeo-maconnisme Et Occultisme En France Sous La IIIe République. Paris: Les Belles Lettres. pp. 285–291 and passim. ISBN 978-2251447117.

- Waterfield, Robin (2005). René Guénon and the Future of the West: The Life and Writings of a 20th-Century Metaphysician. Hillsdale, NY: Sophia Perennis. pp. 33–34. ISBN 978-1597310192.

- Hariche, Samir (2012). El Perennialismo a la luz del Islam. Madrid: Vision Libros. pp. 370–371. ISBN 978-8490116562.

- Jarrige, Michel (1999). L’Église et les francs-maçons dans la tourmente. Croisade de la revue « La Franc-maçonnerie démasquée », 1884-1899. Paris: Arguments. ISBN 978-2909109237.

- Weber, Eugen (1964). Satan franc-maçon. La mystification de Léo Taxil. Paris: Julliard. ISBN 2070288919.

- http://amazingdiscoveries.org/S-deception-Freemason_Lucifer_Albert_Pike

- Lady Queenborough (Edith Starr Miller), Occult Theocrasy, p. 220-223 Abbeville, France: F. Paillart, 1933 ISBN 1442161736

- Pawns in the Game, p. 14-16 (4th Edition, April, 1962), William Guy Carr

- Robert A. Morey, The Origins and Teachings of Freemasonry (Southbridge, Mass.: Crown Publications, Inc., 1990), p 12 ISBN 0925703281.