Aberdeen Breviary

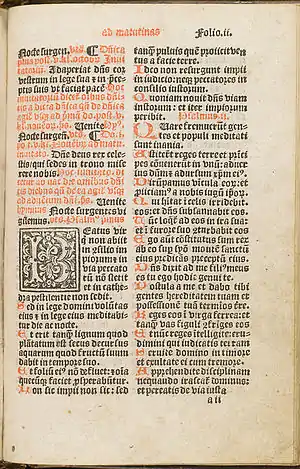

The Aberdeen Breviary (Latin: Breviarium Aberdonense) is a 16th-century Scottish Catholic breviary. It was the first book to be printed in Edinburgh, and in Scotland.

Origin

The creation of the Aberdeen Breviary can be seen as one of the features of the growing Scottish nationalism and identity of the early sixteenth century.[1] In 1507, King James IV, realizing that the existing Sarum Breviary, or Rite, was English in origin, desired the printing of a Scottish version. Since Scotland had no printing press at that time, booksellers Walter Chepman and Androw Myllar of Edinburgh were commissioned to “bring home a printing press” primarily for that purpose.[2]

To create the breviary itself, James sought out William Elphinstone, Bishop of Aberdeen, who had received the king's permission to establish the University of Aberdeen twelve years before.[3] To help him with the undertaking, Elphinstone, in turn, tapped the man who had helped him found the university, Scottish philosopher and historian Hector Boece.[4] The two began their work in 1509, and the first copy, produced as a small octavo, came off the press in 1510.[5]

Contents

Like the Sarum Rite, which had been in use since the twelfth century, the Aberdeen Breviary contained brief lives, or biographies, of the saints as well as the liturgy and canonical hours which were to conform to Roman practice and serve as the standard of Christian worship throughout the country. The saints’ lives, or biographies, in the breviary were all written by either Elphinstone or Boece.[5]

Boece once noted that Elphinstone collected legends of saints from every diocese in Scotland, including both national heroes and local saints. He also noted that Elphinstone devoted time to the study of ancient Scottish histories, especially in the Western Isles, where “tombs of the ancient kings” lie. In addition, some material, such as Lessons for St. Cuthbert, came from the writings of Bede. Some of the collected materials were included verbatim in the breviary, and some were re-written.[6]

However, unlike the Sarum Rite, the Aberdeen work also contained lives of the nation's saints—Scottish saints such as Kentigern, Machar, and Margaret of Scotland. Indeed, historian Jane Geddes has gone so far as to call the Aberdeen Breviary a work of “religious patriotism,” pointing out Scotland's sixteenth-century efforts to establish its own identity. She writes that both Elphinstone and the king “were attempting to direct the apparently growing interest in local cults . . . . toward a range of saints that they identified as Scottish.”[7]

Along with focusing on Scottish saints, Elphinstone sometimes “Scotticized” Irish and continental saints, one of the most interesting being the office of a French saint named Fiacre. Historian Steve Boardman speculates Fiacre appealed to the Scots because of their long-standing hatred of the English in that the French saint was associated with the death of England's despised Henry V.[8] It seems that after the Battle of Agincourt, Henry had allowed his army to pillage Fiacre's shrine, but Fiacre supernaturally prevented the English from carrying their loot beyond the boundaries of his monastery. But that is not all: Henry V died of haemorrhoids on August 30, St. Fiacre's feast day.[9]

Boardman points out, however, that there are a few cases in which Elphinstone and Boece included saints associated with Scotland, but introduced as otherwise. One example is St. Constantine the Great, for whom there were dedicated places of worship in Scotland—at Kilchousland in Kintyre and at Govan—and whom Glasgow even claimed as a native son.[10]

The breviary, which was composed in Latin, includes at the back a small, 16-page book entitled Compassio Beate Marie, which has readings about the relics of St. Andrew, Scotland's patron saint.[2] In addition, at the end of each volume were the Propria Sanctorum, containing prayers and readings to be used only on the feast day of the particular saint.[11] Hymns, responsories, and antiphons were composed for most of the saints in various metres and styles. There are poems as well, although, except for the poem for the office of St. Fiacre, they are not high in quality. All these were to be used as acts of worship.[12]

Extant copies

Only four copies of the Aberdeen Breviary are extant: one in the University of Edinburgh; one in the Library of the Faculty of Advocates, Edinburgh; one in the library of King's College, Aberdeen; and one recently purchased by the National Library of Scotland from the private collection of the Earl of Strathmore in Glamis, Angus.[5][2]

A facsimile of one copy was published in two parts (Pars estiva & Pars hyemalis) in 1854 & 1855, edited by William Blew; this facsimile was issued to members of the Bannatyne, Maitland and Spalding Clubs.[13]

See also

Further reading

- Galbraith, James D. The Sources of the Aberdeen Breviary. M.Litt. thesis, University of Aberdeen, 1970[14]

- Macquarrie, Alan, et al. Legends of Scottish Saints: readings, hynmns and prayers for the commemorations of Scottish saints from the Aberdeen Breviary. Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2012

Notes

- Von Contzen, Eva (2016). The Scottish Legendary: Towards a Poetics of Hagiographic Narration. Manchester: Manchester UP. p. 232. ISBN 978-0719095962. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- "Glamis Copy of Aberdeen Breviary - a Significant Addition". National Library of Scotland. Archived from the original on 9 July 2018. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- "Bishop William Elphinstone". Undiscovered Scotland. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- Geddes, Jane (2016). Medieval Art, Architecture and Archaeology in the Dioceses of Aberdeen and Moray. London: Routledge. p. 143. ISBN 978-1138640689. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- "The Aberdeen Breviary". Catholic Encyclopedia. New Advent. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- Boardman, Steve; Williamson, Ella (2010). The Cult of Saints and the Virgin Mary in Medieval Scotland. Woodbridge: Boydell. pp. 146–49. ISBN 9781843835622. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- Geddes. Medieval Art. p. 241.

- Boardman. Cult of Saints. p. 150.

- "St. Fiacre of Breuil, & Kilfiachra (Ireland)". Celtic and Old English Saints. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- Boardman. Cult of Saints. p. 149.

- Boardman. Cult of Saints. p. 143.

- Boardman. Cult of Saints. pp. 151–52.

- Based on the record in JISC Library Hub

- Based on record in JISC Library Hub