Achille-Antoine Hermitte

Achille-Antoine Hermitte (1840–c. 1870) was a French architect who is known for designing the Hong Kong City Hall and the Palais du Gouverneur, Saigon. His life is not well-documented and there is uncertainty about the date and place of his death. His only surviving building is the small Chapel of the Tomb of St Francis Xavier on Shangchuan Island, southwest of Guangzhou.

Achille-Antoine Hermitte | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) The Governor's Palace in Saigon, 1873 | |

| Born | 1840 Paris, France |

| Died | c. 1870 Saigon, Cochinchina |

| Nationality | French |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Known for | Palais du Gouverneur, Saigon |

Life

Achille-Antoine Hermitte was born in Paris in 1840 in Paris. There are no records of his parents or childhood. He attended the École Royale d'Architecture de Paris, part of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, a school that was not known for developing original architects.[1] He graduated in 1860 as a student in the second class. There is no record that he received any prizes. Early in his career he was apprenticed to Douillard frères(fr)(fr) of Nantes.[2]

Hermitte was involved in construction of the Roman Catholic Cathedral of the Sacred Heart of Jesus in Guangzhou (Canton), China, but his role is unclear.[2] Eudore de Colomban in his biography of Zéphyrin Guillemin, Bishop of Canton, wrote that around 1865 or 1866 a new, 26-year-old architect had arrived, but work on the cathedral was still making little progress. This probably refers to Hermitte.[3] Hermitte seems to have been based in Hong Kong while he did work for the bishop and others.[4] This included a chapel to mark the place where Saint Francis Xavier had died on Shangchuan Island, southwest of Canton. It replaced a ruined memorial to the saint.[5]

.jpg.webp)

In 1865 Hermitte entered the competition for the design of the Hong Kong City Hall.[6] Around the end of 1865 Hermitte won the competition, in which the selection process was far from transparent.[7] The City Hall and Hermitte's other buildings were erected by skilled Hakka stonemasons from Wuhua in eastern Guangdong. They were probably chosen in part because they were more friendly to foreigners and tolerant of Christianity then other local people.[8] By October 1868 the Hong Kong City Hall was almost finished, although work still continued into the spring of 1869. Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, opened the building in a ceremony on 28 June 1869.[9]

In 1865 a competition for a new gubernatorial palace in Saigon was announced. There were two entries, one of which may perhaps have been Hermitte's.[10] The Governor of Cochinchina, Admiral Pierre-Paul de La Grandière, later made Hermitte head of his architectural department, as recommended by admirals Pierre-Gustave Roze and Gustave Ohier, who had met him in Hong Kong. Hermitte's priority was to design a new Governor's Mansion since the existing wooden building was in disrepair. La Grandière laid the cornerstone for this building on 23 March 1868, a block of blue granite from Biên Hòa containing a lead coffer that in turn contained newly-minted gold, silver and coin coins of Napoleon III.[11]

Work on the huge Saigon Governor's Palace began in earnest when Hermitte brought in skilled workmen from Canton and Hong Kong. The site of the Palais du Gouverneur turned out to be waterlogged and the foundations required constant repair to counteract subsidence throughout the building's life.[12] Most of the materials were imported from France, adding to the cost.[13] Completion of construction was celebrated informally on 25 September 1869 with a banquet and a ball for everyone involved in the project.[12] The final, formal opening of the palace took place in 1873 under Governor Marie Jules Dupré.[13] Dupré moved into the building that year, and the decorations were completed in 1875. The total cost was 12 million francs, over a quarter of the budget for public works in Cochinchina.[14]

In 1869 Hermitte was listed as the architect of the colony, head of the civil buildings service, on leave. Codry was listed as architect, acting head of service.[15] An 1872 account of the Hôtel du Gouvernment in Saigon states that Hermitte died in Saigon in 1870 and was succeeded by M. Codry.[16][lower-alpha 1] This date and place is uncertain. Around 1870 Bishop Guillemin wrote, "... our architect, greatly weakened by his work and his period in Saigon, has just returned to France leaving on our shoulders all of the direction and care of the works of our church (cathedral)".[4]

Work

Hong Kong City Hall

The Hong Kong City Hall was a Victorian-style building on the edge of Victoria Harbour that was meant to be a hub for both cultural and administrative activities.[18] The requirements for the two-storey building included kitchens and rooms for the servants in the basement. The ground floor would have an entrance hall, cloak room, secretary' room and a 500-seat theatre, exclusive of a gallery, with a 28 by 35 feet (8.5 by 10.7 m) proscenium-arched stage. The first floor would have St Andrew's Hall, with space for an orchestra, a banqueting hall and an annex that led to the theatre's gallery. The building would also hold a public library that could accommodate 10,000 books and the museum of the South China Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society.[10] According to an editorial in the Hong Kong Daily Press Hermitte's design did not meet all the requirements. The theatre was too small and did not have an entrance from the Praya.[7] The city hall was demolished in 1933.[19]

Chapel of the Tomb of St Francis Xavier

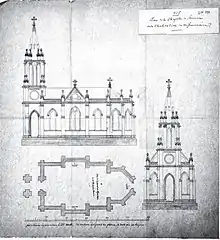

In early 1867 Bishop Guillemin wrote that, "M. Hermitte, our architect, has given us the plan which he wished to donate for St. Francis and one of our missionaries, M. Braud, is presently in place putting it into effect. Although small, the chapel will be beautiful, graceful, and its slender spire will thus raise it from the top of this rock as the soul of the Saint was raised from earth to heaven."[4] The small chapel was ready early in 1869. The bishop wrote that it, "only measured about 10 feet long and 30 feet wide, with a small steeple rising 60 feet above; but its Gothic style, its position on a raised rock thrusting into the sea, its slender, pyramidal steeple that dominated all around it gave it a perfect elegance and gracefulness.[4]

The chapel was in fact 15.75 by 9.19 metres (51.7 by 30.2 ft), and the spire rose 19.05 metres (62.5 ft) above the floor. There was a slab in the floor that marked the place where Saint Francis Xavier had died, and there were three small wooden altars, two in niches on the north and south sides and one in the apse.[20] The chapel was consecrated at 8 in the morning on 25 April 1869 in a ceremony attended by about 200 Europeans and 100 Chinese Christians.[20] The chapel was sacked during the Sino-French war of 1884, and badly damaged by a typhoon in 1888-89. It was partially restored in 1910 and 1932.[21] It was again damaged during the Japanese occupation, then neglected until the Taishan district government completely refurbished it in 1986. In 2006 it was again restored to make the 500th anniversary of Saint Francis's birth.[22]

Saigon Governor's Palace

The Saigon Governor's Palace was intended to impress the local people with France's power and wealth.[23] The building was in neo-Baroque style.[14] The walls were in yellow stucco, on foundations of granite imported from France. The facade was decorated by carvings in smooth white stone, also imported. The central pavilion had marble floors, while the other floors were tiled. The palace was T-shaped, and had two rows of arched windows along the front, looking out on the city. Offices and official reception rooms were on the ground floor, with the governor's residential rooms above. The leg of the T held the reception hall and adjoining ballrooms, surrounded by lush foliage.[23] During a coup attempt on 27 February 1962 two airplanes bombed the building and demolished the left wing. The president ordered the whole building demolished and the present Unification Palace was built in its place.[14]

Notes

- In 1871 the Saigon municipal council voted to build a city hall. Hermitte's successor Pierre Codry provided a design and work was started, then cancelled almost immediately due to cost.[17]

Citations

- Davies 2014, p. 201.

- Davies 2014, p. 202.

- Davies & 戴偉思 2016, p. 92.

- Davies & 戴偉思 2016, p. 98.

- Davies & 戴偉思 2016, p. 96.

- Davies 2014, p. 204.

- Davies 2014, p. 206.

- Farris 2016, p. 132.

- Davies 2014, p. 208.

- Davies 2014, p. 205.

- Davies 2014, p. 207.

- Davies 2014, p. 209.

- Davies 2014, p. 210.

- Doling 2014.

- Cochin China 1869, p. 113.

- Charton 1872.

- Wright 1991, p. 178.

- Twenty Years and Beyond...Hong Kong.

- Davies & 戴偉思 2016, p. 93.

- Davies & 戴偉思 2016, p. 99.

- Davies & 戴偉思 2016, p. 105.

- Davies & 戴偉思 2016, p. 106.

- Demery 2013, PT58.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Achille-Antoine Hermitte. |

Sources

- Charton, Edouard, ed. (1872), "The Hôtel du Gouvernment in Saigon: Capital of our Cochinchina territories", Le Magasin Pittoresque, retrieved 2018-07-17 – via Historic Vietnam

- Cochin China (1869), Annuaire de la Cochinchine pour l'Année (in French), retrieved 2018-07-17

- Davies, Stephen (2014), "Achille-Antoine Hermitte (1840–70?)", Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong Branch, Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong Branch, 54: 201–216, JSTOR jroyaaisasocihkb.54.201

- Davies, Stephen; 戴偉思 (2016), "Achille-Antoine Hermitte's Surviving Building / 阿基里‧ 安當‧ 埃爾米特的倖存建築", Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong Branch, Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong Branch, 56: 92–110, JSTOR jroyaaisasocihkb.56.92

- Demery, Monique Brinson (2013), Finding the Dragon Lady: The Mystery of Vietnam's Madame Nhu, Hachette UK, ISBN 978-1610392822, retrieved 2018-07-17

- Doling, Tim (6 August 2014), "Saigon's Palais Norodom – A Palace Without Purpose", Historic Vietnam, retrieved 2017-07-17

- Farris, Johnathan Andrew (2016-07-01), Enclave to Urbanity: Canton, Foreigners, and Architecture from the Late Eighteenth to the Early Twentieth Centuries, Hong Kong University Press, ISBN 978-988-8208-87-6, retrieved 2018-07-17

- Twenty Years and Beyond: Culture and Museums in Hong Kong's Past, Present, and Future, Hong Kong: University of Hong Kong, 15 September 2017, retrieved 2018-07-17

- Wright, Gwendolyn (1991), The Politics of Design in French Colonial Urbanism, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-90848-9, retrieved 2018-07-17