Airport

An airport is an aerodrome with extended facilities, mostly for commercial air transport.[1][2] Airports often have facilities to store and maintain aircraft, and a control tower. An airport consists of a landing area, which comprises an aerially accessible open space including at least one operationally active surface such as a runway for a plane to take off[3] or a helipad,[4] and often includes adjacent utility buildings such as control towers, hangars[5] and terminals. Larger airports may have airport aprons, taxiway bridges, air traffic control centres, passenger facilities such as restaurants and lounges, and emergency services. In some countries, the US in particular, airports also typically have one or more fixed-base operators, serving general aviation.

An airport solely serving helicopters is called a heliport. An airport for use by seaplanes and amphibious aircraft is called a seaplane base. Such a base typically includes a stretch of open water for takeoffs and landings, and seaplane docks for tying-up.

An international airport has additional facilities for customs and passport control as well as incorporating all the aforementioned elements. Such airports rank among the most complex and largest of all built typologies, with 15 of the top 50 buildings by floor area being airport terminals.[6]

Terminology

The terms aerodrome, airfield, and airstrip also refer to airports, and the terms heliport, seaplane base, and STOLport refer to airports dedicated exclusively to helicopters, seaplanes, and short take-off and landing aircraft.

In colloquial use in certain environments, the terms airport and aerodrome are often interchanged. However, in general, the term airport may imply or confer a certain stature upon the aviation facility that other aerodromes may not have achieved. In some jurisdictions, airport is a legal term of art reserved exclusively for those aerodromes certified or licensed as airports by the relevant national aviation authority after meeting specified certification criteria or regulatory requirements.[7]

That is to say, all airports are aerodromes, but not all aerodromes are airports. In jurisdictions where there is no legal distinction between aerodrome and airport, which term to use in the name of an aerodrome may be a commercial decision. In US technical/legal usage, landing area is used instead of aerodrome, and airport means "a landing area used regularly by aircraft for receiving or discharging passengers or cargo".[8]

Management

Smaller or less-developed airfields, which represent the vast majority, often have a single runway shorter than 1,000 m (3,300 ft). Larger airports for airline flights generally have paved runways of 2,000 m (6,600 ft) or longer. Skyline Airport in Inkom, Idaho has a runway that is only 122 m (400 ft) long.[9]

In the United States, the minimum dimensions for dry, hard landing fields are defined by the FAR Landing And Takeoff Field Lengths. These include considerations for safety margins during landing and takeoff.

The longest public-use runway in the world is at Qamdo Bamda Airport in China. It has a length of 5,500 m (18,045 ft). The world's widest paved runway is at Ulyanovsk Vostochny Airport in Russia and is 105 m (344 ft) wide.

As of 2009, the CIA stated that there were approximately 44,000 "airports or airfields recognizable from the air" around the world, including 15,095 in the US, the US having the most in the world.[10][11]

Airport ownership and operation

Most of the world's large airports are owned by local, regional, or national government bodies who then lease the airport to private corporations who oversee the airport's operation. For example, in the UK the state-owned British Airports Authority originally operated eight of the nation's major commercial airports – it was subsequently privatized in the late 1980s, and following its takeover by the Spanish Ferrovial consortium in 2006, has been further divested and downsized to operating just Heathrow. Germany's Frankfurt Airport is managed by the quasi-private firm Fraport. While in India GMR Group operates, through joint ventures, Indira Gandhi International Airport and Rajiv Gandhi International Airport. Bengaluru International Airport and Chhatrapati Shivaji International Airport are controlled by GVK Group. The rest of India's airports are managed by the Airports Authority of India. In Pakistan nearly all civilian airports are owned and operated by the Pakistan Civil Aviation Authority except for Sialkot International Airport which has the distinction of being the first privately owned public airport in Pakistan and South Asia.

In the US, commercial airports are generally operated directly by government entities or government-created airport authorities (also known as port authorities), such as the Los Angeles World Airports authority that oversees several airports in the Greater Los Angeles area, including Los Angeles International Airport.

In Canada, the federal authority, Transport Canada, divested itself of all but the remotest airports in 1999/2000. Now most airports in Canada are owned and operated by individual legal authorities or are municipally owned.

Many US airports still lease part or all of their facilities to outside firms, who operate functions such as retail management and parking. All US commercial airport runways are certified by the FAA[12] under the Code of Federal Regulations Title 14 Part 139, "Certification of Commercial Service Airports"[13] but maintained by the local airport under the regulatory authority of the FAA.

Despite the reluctance to privatize airports in the US (contrary to the FAA sponsoring a privatization program since 1996), the government-owned, contractor-operated (GOCO) arrangement is the standard for the operation of commercial airports in the rest of the world.

Airport funding

The Airport & Airway Trust Fund (AATF) was created by the Airport and Airway Development in 1970 which finances aviation programs in the United States.[14] Airport Improvement Program (AIP), Facilities and Equipment (F&E), and Research, Engineering, and Development (RE&D) are the three major accounts of Federal Aviation Administration which are financed by the AATF, as well as pays for the FAA's Operation and Maintenance (O&M) account.[15] The funding of these accounts are dependent on the taxes the airports generate of revenues. Passenger tickets, fuel, and cargo tax are the taxes that are paid by the passengers and airlines help fund these accounts.[16]

Airport revenue

Airports revenues are divided into three major parts: aeronautical revenue, non-aeronautical revenue, and non-operating revenue. Aeronautical revenue makes up 56%, non-aeronautical revenue makes up 40%, and non-operating revenue makes up 4% of the total revenue of airports.[17]

Aeronautical revenue

Aeronautical revenue are generated through airline rents and landing, passenger service, parking, and hangar fees. Landing fees are charged per aircraft for landing an airplane in the airport property.[18] Landing fees are calculated through the landing weight and the size of the aircraft which varies but most of the airports have a fixed rate and a charge extra for extra weight.[19] Passenger service fees are charges per passengers for the facilities used on a flight like water, food, wifi and shows which is paid while paying for an airline ticket. Aircraft parking is also a major revenue source for airports. Aircraft are parked for a certain amount of time before or after takeoff and have to pay to park there.[20] Every airport has his own rates of parking but at John F Kennedy airport in New York City charges $45 per hour for the plane of 100,000 pounds and the price increases with weight.[21]

Non-aeronautical revenue

Non-aeronautical revenue is gained through things other than aircraft operations. It includes lease revenue from compatible land-use development, non-aeronautical building leases, retail and concession sales, rental car operations, parking and in-airport advertising.[22] Concession revenue is one big part of non-aeronautical revenue airports makes through duty free, bookstores, restaurants and money exchange.[20] Car parking is a growing source of revenue for airports, as more people use the parking facilities of the airport. O'Hare International Airport in Chicago charges $2 per hour for every car.[23]

Landside and airside areas

Airports are divided into landside and airside zones. The landside is subject to fewer special laws and is part of the public realm, while access to the airside zone is tightly controlled. The airside area includes all parts of the airport around the aircraft, and the parts of the buildings that are restricted to staff, and sections of these extended to travelling, airside shopping, dining, or waiting passengers. Passengers and staff must be checked by security before being permitted to enter the airside zone. Conversely, passengers arriving from an international flight must pass through border control and customs to access the landside area, in which they exit, unless in airside transit. Most multi-terminal airports have (variously termed) flight/passenger/air connections buses, moving walkways and/or people movers for inter-terminal airside transit. Their airlines can arrange for baggage to be routed directly to the passenger's destination. Most major airports issue a secure keycard, an airside pass to employees, to assist in their reliable, standardized and efficient verification of identity.

Facilities

.jpg.webp)

A terminal is a building with passenger facilities. Small airports have one terminal. Large ones often have multiple terminals, though some large airports like Amsterdam Airport Schiphol still have one terminal. The terminal has a series of gates, which provide passengers with access to the plane.

The following facilities are essential for departing passengers:

- Check-in facilities, including a baggage drop-off

- Security clearance gates

- Passport control (for some international flights)

- Gates

- Waiting areas

The following facilities are essential for arriving passengers:

- Passport control (international arrivals only)

- Baggage reclaim facilities, often in the form of a carousel

- Customs (international arrivals only)

- A landside meeting place

For both sets of passengers, there must be a link between the passenger facilities and the aircraft, such as jet bridges or airstairs. There also needs to be a baggage handling system, to transport baggage from the baggage drop-off to departing planes, and from arriving planes to the baggage reclaim.

The area where the aircraft park to load passengers and baggage is known as an apron or ramp (or incorrectly,[24] "the tarmac").

Airports with international flights have customs and immigration facilities. However, as some countries have agreements that allow travel between them without customs and immigrations, such facilities are not a definitive need for an international airport. International flights often require a higher level of physical security, although in recent years, many countries have adopted the same level of security for international and domestic travel.

"Floating airports" are being designed which could be located out at sea and which would use designs such as pneumatic stabilized platform technology.

Airport security

Airport security normally requires baggage checks, metal screenings of individual persons, and rules against any object that could be used as a weapon. Since the September 11 attacks and the Real ID Act of 2005, airport security has dramatically increased and got tighter and stricter than ever before.

Products and services

Most major airports provide commercial outlets for products and services. Most of these companies, many of which are internationally known brands, are located within the departure areas. These include clothing boutiques and restaurants and in the US amounted to $4.2 billion in 2015.[25] Prices charged for items sold at these outlets are generally higher than those outside the airport. However, some airports now regulate costs to keep them comparable to "street prices". This term is misleading as prices often match the manufacturers' suggested retail price (MSRP) but are almost never discounted.

Many new airports include walkthrough duty-free stores that require air passengers to enter a retail store upon exiting security. [26] Airport planners sometimes incorporate winding routes within these stores such that passengers encounter more goods as they walk towards their gate. Planners also install artworks next to the airport’s shops in order to draw passengers into the stores.

Apart from major fast food chains, some airport restaurants offer regional cuisine specialties for those in transit so that they may sample local food or culture without leaving the airport.[27]

Some airport structures include on-site hotels built within or attached to a terminal building. Airport hotels have grown popular due to their convenience for transient passengers and easy accessibility to the airport terminal. Many airport hotels also have agreements with airlines to provide overnight lodging for displaced passengers.

Major airports in such countries as Russia and Japan offer miniature sleeping units within the airport that are available for rent by the hour. The smallest type is the capsule hotel popular in Japan. A slightly larger variety is known as a sleep box. An even larger type is provided by the company YOTEL.

Premium and VIP services

Airports may also contain premium and VIP services. The premium and VIP services may include express check-in and dedicated check-in counters. These services are usually reserved for first and business class passengers, premium frequent flyers, and members of the airline's clubs. Premium services may sometimes be open to passengers who are members of a different airline's frequent flyer program. This can sometimes be part of a reciprocal deal, as when multiple airlines are part of the same alliance, or as a ploy to attract premium customers away from rival airlines.

Sometimes these premium services will be offered to a non-premium passenger if the airline has made a mistake in handling of the passenger, such as unreasonable delays or mishandling of checked baggage.

Airline lounges frequently offer free or reduced cost food, as well as alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages. Lounges themselves typically have seating, showers, quiet areas, televisions, computer, Wi-Fi and Internet access, and power outlets that passengers may use for their electronic equipment. Some airline lounges employ baristas, bartenders and gourmet chefs.

Airlines sometimes operate multiple lounges within the one airport terminal allowing ultra-premium customers, such as first class customers, additional services, which are not available to other premium customers. Multiple lounges may also prevent overcrowding of the lounge facilities.

Cargo and freight service

In addition to people, airports move cargo around the clock. Cargo airlines often have their own on-site and adjacent infrastructure to transfer parcels between ground and air.

Cargo Terminal Facilities are areas where international airports export cargo has to be stored after customs clearance and prior to loading on the aircraft. Similarly import cargo that is offloaded needs to be in bond before the consignee decides to take delivery. Areas have to be kept aside for examination of export and import cargo by the airport authorities. Designated areas or sheds may be given to airlines or freight forward ring agencies.

Every cargo terminal has a landside and an airside. The landside is where the exporters and importers through either their agents or by themselves deliver or collect shipments while the airside is where loads are moved to or from the aircraft. In addition cargo terminals are divided into distinct areas – export, import and interline or transshipment.

Access and onward travel

Airports require parking lots, for passengers who may leave the cars at the airport for a long period of time. Large airports will also have car-rental firms, taxi ranks, bus stops and sometimes a train station.

Many large airports are located near railway trunk routes for seamless connection of multimodal transport, for instance Frankfurt Airport, Amsterdam Airport Schiphol, London Heathrow Airport, Tokyo Haneda Airport, Tokyo Narita Airport, London Gatwick Airport and London Stansted Airport. It is also common to connect an airport and a city with rapid transit, light rail lines or other non-road public transport systems. Some examples of this would include the AirTrain JFK at John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York, Link Light Rail that runs from the heart of downtown Seattle to Seattle–Tacoma International Airport, and the Silver Line T at Boston's Logan International Airport by the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA). Such a connection lowers risk of missed flights due to traffic congestion. Large airports usually have access also through controlled-access highways ('freeways' or 'motorways') from which motor vehicles enter either the departure loop or the arrival loop.

Internal transport

The distances passengers need to move within a large airport can be substantial. It is common for airports to provide moving walkways, buses, and rail transport systems. Some airports like Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport and London Stansted Airport have a transit system that connects some of the gates to a main terminal. Airports with more than one terminal have a transit system to connect the terminals together, such as John F. Kennedy International Airport, Mexico City International Airport and London Gatwick Airport.

Airport operations

There are three types of surface that aircraft operate on:

- Runways, for takeoff and landing

- Taxiways, where planes "taxi" (transfer to and from a runway)

- Apron or ramp: a surface where planes are parked, loaded, unloaded or refuelled.

Air traffic control

.jpg.webp)

Air traffic control (ATC) is the task of managing aircraft movements and making sure they are safe, orderly and expeditious. At the largest airports, air traffic control is a series of highly complex operations that requires managing frequent traffic that moves in all three dimensions.

A "towered" or "controlled" airport has a control tower where the air traffic controllers are based. Pilots are required to maintain two-way radio communication with the controllers, and to acknowledge and comply with their instructions. A "non-towered" airport has no operating control tower and therefore two-way radio communications are not required, though it is good operating practice for pilots to transmit their intentions on the airport's common traffic advisory frequency (CTAF) for the benefit of other aircraft in the area. The CTAF may be a Universal Integrated Community (UNICOM), MULTICOM, Flight Service Station (FSS), or tower frequency.

The majority of the world's airports are small facilities without a tower. Not all towered airports have 24/7 ATC operations. In those cases, non-towered procedures apply when the tower is not in use, such as at night. Non-towered airports come under area (en-route) control. Remote and virtual tower (RVT) is a system in which ATC is handled by controllers who are not present at the airport itself.

Air traffic control responsibilities at airports are usually divided into at least two main areas: ground and tower, though a single controller may work both stations. The busiest airports may subdivide responsibilities further, with clearance delivery, apron control, and/or other specialized ATC stations.

Ground control

Ground control is responsible for directing all ground traffic in designated "movement areas", except the traffic on runways. This includes planes, baggage trains, snowplows, grass cutters, fuel trucks, stair trucks, airline food trucks, conveyor belt vehicles and other vehicles. Ground Control will instruct these vehicles on which taxiways to use, which runway they will use (in the case of planes), where they will park, and when it is safe to cross runways. When a plane is ready to takeoff it will be turned over to tower control. Conversely, after a plane has landed it will depart the runway and be "handed over" from Tower to Ground Control.

Tower control

Tower control is responsible for aircraft on the runway and in the controlled airspace immediately surrounding the airport. Tower controllers may use radar to locate an aircraft's position in 3D space, or they may rely on pilot position reports and visual observation. They coordinate the sequencing of aircraft in the traffic pattern and direct aircraft on how to safely join and leave the circuit. Aircraft which are only passing through the airspace must also contact tower control to be sure they remain clear of other traffic.

Traffic pattern

At all airports the use of a traffic pattern (often called a traffic circuit outside the US) is possible. They may help to assure smooth traffic flow between departing and arriving aircraft. There is no technical need within modern commercial aviation for performing this pattern, provided there is no queue. And due to the so-called SLOT-times, the overall traffic planning tend to assure landing queues are avoided. If for instance an aircraft approaches runway 17 (which has a heading of approx. 170 degrees) from the north (coming from 360/0 degrees heading towards 180 degrees), the aircraft will land as fast as possible by just turning 10 degrees and follow the glidepath, without orbit the runway for visual reasons, whenever this is possible. For smaller piston engined airplanes at smaller airfields without ILS equipment, things are very different though.

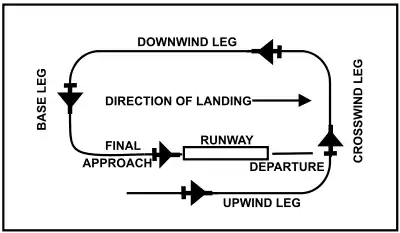

Generally, this pattern is a circuit consisting of five "legs" that form a rectangle (two legs and the runway form one side, with the remaining legs forming three more sides). Each leg is named (see diagram), and ATC directs pilots on how to join and leave the circuit. Traffic patterns are flown at one specific altitude, usually 800 or 1,000 ft (244 or 305 m) above ground level (AGL). Standard traffic patterns are left-handed, meaning all turns are made to the left. One of the main reason for this is that pilots sit on the left side of the airplane, and a Left-hand patterns improves their visibility of the airport and pattern. Right-handed patterns do exist, usually because of obstacles such as a mountain, or to reduce noise for local residents. The predetermined circuit helps traffic flow smoothly because all pilots know what to expect, and helps reduce the chance of a mid-air collision.

At controlled airports, a circuit can be in place but is not normally used. Rather, aircraft (usually only commercial with long routes) request approach clearance while they are still hours away from the airport; the destination airport can then plan a queue of arrivals, and planes will be guided into one queue per active runway for a "straight-in" approach. While this system keeps the airspace free and is simpler for pilots, it requires detailed knowledge of how aircraft are planning to use the airport ahead of time and is therefore only possible with large commercial airliners on pre-scheduled flights. The system has recently become so advanced that controllers can predict whether an aircraft will be delayed on landing before it even takes off; that aircraft can then be delayed on the ground, rather than wasting expensive fuel waiting in the air.

Navigational aids

There are a number of aids, both visual and electronic, though not at all airports. A visual approach slope indicator (VASI) helps pilots fly the approach for landing. Some airports are equipped with a VHF omnidirectional range (VOR) to help pilots find the direction to the airport. VORs are often accompanied by a distance measuring equipment (DME) to determine the distance to the VOR. VORs are also located off airports, where they serve to provide airways for aircraft to navigate upon. In poor weather, pilots will use an instrument landing system (ILS) to find the runway and fly the correct approach, even if they cannot see the ground. The number of instrument approaches based on the use of the Global Positioning System (GPS) is rapidly increasing and may eventually become the primary means for instrument landings.

Larger airports sometimes offer precision approach radar (PAR), but these systems are more common at military air bases than civilian airports. The aircraft's horizontal and vertical movement is tracked via radar, and the controller tells the pilot his position relative to the approach slope. Once the pilots can see the runway lights, they may continue with a visual landing.

Taxiway signs

Airport guidance signs provide direction and information to taxiing aircraft and airport vehicles. Smaller aerodromes may have few or no signs, relying instead on diagrams and charts.

Lighting

.jpg.webp)

Many airports have lighting that help guide planes using the runways and taxiways at night or in rain or fog.

On runways, green lights indicate the beginning of the runway for landing, while red lights indicate the end of the runway. Runway edge lighting consists of white lights spaced out on both sides of the runway, indicating the edges. Some airports have more complicated lighting on the runways including lights that run down the centerline of the runway and lights that help indicate the approach (an approach lighting system, or ALS). Low-traffic airports may use pilot-controlled lighting to save electricity and staffing costs.

Along taxiways, blue lights indicate the taxiway's edge, and some airports have embedded green lights that indicate the centerline.

Weather observations

Weather observations at the airport are crucial to safe takeoffs and landings. In the US and Canada, the vast majority of airports, large and small, will either have some form of automated airport weather station, whether an AWOS, ASOS, or AWSS, a human observer or a combination of the two. These weather observations, predominantly in the METAR format, are available over the radio, through automatic terminal information service (ATIS), via the ATC or the flight service station.

Planes take-off and land into the wind to achieve maximum performance. Because pilots need instantaneous information during landing, a windsock can also be kept in view of the runway. Aviation windsocks are made with lightweight material, withstand strong winds and some are lit up after dark or in foggy weather. Because visibility of windsocks is limited, often multiple glow-orange windsocks are placed on both sides of the runway.[28]

Airport ground crew (ground handling)

Most airports have groundcrew handling the loading and unloading of passengers, crew, baggage and other services. Some groundcrew are linked to specific airlines operating at the airport.

Among the vehicles that serve an airliner on the ground are:

- A tow tractor to move the aircraft in and out of the berth.

- A jet bridge (in some airports) or stairs unit to allow passengers to embark and disembark.

- A ground power unit for supplying electricity. As the engines will be switched off, they will not be generating electricity as they do in flight.

- A cleaning service.

- A catering service to deliver food and drinks for a flight.

- A toilet waste truck to empty the tank which holds the waste from the toilets in the aircraft.

- A water truck to fill the water tanks of the aircraft.

- A refueling vehicle. The fuel may come from a tanker, or from underground fuel tanks.

- A conveyor belt unit for loading and unloading luggage.

- A vehicle to transport luggage to and from the terminal.

The length of time an aircraft remains on the ground in between consecutive flights is known as "turnaround time". Airlines pay great attention to minimizing turnaround times in an effort to keep aircraft use (flying time) high, with times scheduled as low as 25 minutes for jet aircraft operated by low-cost carriers on narrow-body aircraft.

Maintenance management

Like industrial equipment or facility management, airports require tailor-made maintenance management due to their complexity. With many tangible assets spread over a large area in different environments, these infrastructures must therefore effectively monitor these assets and store spare parts to maintain them at an optimal level of service.[29]

To manage these airport assets, several solutions are competing for the market: CMMS (computerized maintenance management system) predominate, and mainly enable a company's maintenance activity to be monitored, planned, recorded and rationalized.[29]

Safety management

Aviation safety is an important concern in the operation of an airport, and almost every airfield includes equipment and procedures for handling emergency situations. Airport crash tender crews are equipped for dealing with airfield accidents, crew and passenger extractions, and the hazards of highly flammable aviation fuel. The crews are also trained to deal with situations such as bomb threats, hijacking, and terrorist activities.

Hazards to aircraft include debris, nesting birds, and reduced friction levels due to environmental conditions such as ice, snow, or rain. Part of runway maintenance is airfield rubber removal which helps maintain friction levels. The fields must be kept clear of debris using cleaning equipment so that loose material does not become a projectile and enter an engine duct (see foreign object damage). In adverse weather conditions, ice and snow clearing equipment can be used to improve traction on the landing strip. For waiting aircraft, equipment is used to spray special deicing fluids on the wings.

Many airports are built near open fields or wetlands. These tend to attract bird populations, which can pose a hazard to aircraft in the form of bird strikes. Airport crews often need to discourage birds from taking up residence.

Some airports are located next to parks, golf courses, or other low-density uses of land. Other airports are located near densely populated urban or suburban areas.

An airport can have areas where collisions between aircraft on the ground tend to occur. Records are kept of any incursions where aircraft or vehicles are in an inappropriate location, allowing these "hot spots" to be identified. These locations then undergo special attention by transportation authorities (such as the FAA in the US) and airport administrators.

During the 1980s, a phenomenon known as microburst became a growing concern due to aircraft accidents caused by microburst wind shear, such as Delta Air Lines Flight 191. Microburst radar was developed as an aid to safety during landing, giving two to five minutes' warning to aircraft in the vicinity of the field of a microburst event.

Some airfields now have a special surface known as soft concrete at the end of the runway (stopway or blastpad) that behaves somewhat like styrofoam, bringing the plane to a relatively rapid halt as the material disintegrates. These surfaces are useful when the runway is located next to a body of water or other hazard, and prevent the planes from overrunning the end of the field.

Airports often have on-site firefighters to respond to emergencies. These use specialized vehicles, known as airport crash tenders.

Environmental concerns and sustainability

Aircraft noise is a major cause of noise disturbance to residents living near airports. Sleep can be affected if the airports operate night and early morning flights. Aircraft noise occurs not only from take-offs and landings, but also from ground operations including maintenance and testing of aircraft. Noise can have other health effects as well. Other noise and environmental concerns are vehicle traffic causing noise and pollution on roads leading to airport.[30]

The construction of new airports or addition of runways to existing airports, is often resisted by local residents because of the effect on countryside, historical sites, and local flora and fauna. Due to the risk of collision between birds and aircraft, large airports undertake population control programs where they frighten or shoot birds.

The construction of airports has been known to change local weather patterns. For example, because they often flatten out large areas, they can be susceptible to fog in areas where fog rarely forms. In addition, they generally replace trees and grass with pavement, they often change drainage patterns in agricultural areas, leading to more flooding, run-off and erosion in the surrounding land.[31] Airports are often built on low-lying coastal land, globally 269 airports are at risk of coastal flooding now.[32] A temperature rise of 2oC – consistent with the Paris Agreement - would lead to 100 airports being below mean sea level and 364 airports at risk of flooding.[32] If global mean temperature rise exceeds this then as many as 572 airports will be at risk by 2100, leading to major disruptions without appropriate adaptation.[32]

Some of the airport administrations prepare and publish annual environmental reports to show how they consider these environmental concerns in airport management issues and how they protect environment from airport operations. These reports contain all environmental protection measures performed by airport administration in terms of water, air, soil and noise pollution, resource conservation and protection of natural life around the airport.

A 2019 report from the Cooperative Research Programs of the US Transportation Research Board showed all airports have a role to play in advancing greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction initiatives. Small airports have demonstrated leadership by using their less complex organizational structure to implement newer technologies and to serve as a providing ground for their feasibility. Large airports have the economic stability and staff resources necessary to grow in-house expertise and fund comprehensive new programs.[33]

A growing number of airports are installing solar photovoltaic arrays to offset their electricity use.[34][35] The National Renewable Energy Lab has shown this can be done safely.[36]

The world's first airport to be fully powered by solar energy is located at Kochi, India. Another airport known for considering environmental concerns is Seymour Airport in the Galapagos Islands.

Military air base

An airbase, sometimes referred to as an air station or airfield, provides basing and support of military aircraft. Some airbases, known as military airports, provide facilities similar to their civilian counterparts. For example, RAF Brize Norton in the UK has a terminal which caters to passengers for the Royal Air Force's scheduled flights to the Falkland Islands. Some airbases are co-located with civilian airports, sharing the same ATC facilities, runways, taxiways and emergency services, but with separate terminals, parking areas and hangars. Bardufoss Airport, Bardufoss Air Station in Norway and Pune Airport in India are examples of this.

An aircraft carrier is a warship that functions as a mobile airbase. Aircraft carriers allow a naval force to project air power without having to depend on local bases for land-based aircraft. After their development in World War I, aircraft carriers replaced the battleship as the centrepiece of a modern fleet during World War II.

Airport designation and naming

Most airports in the United States are designated "private-use airports" meaning that, whether publicly- or privately-owned, the airport is not open or available for use by the public (although use of the airport may be made available by invitation of the owner or manager).

Airports are uniquely represented by their IATA airport code and ICAO airport code.

Most airport names include the location. Many airport names honour a public figure, commonly a politician (e.g., Charles de Gaulle Airport, George Bush Intercontinental Airport, O.R. Tambo International Airport), a monarch (e.g. Chhatrapati Shivaji International Airport, King Shaka International Airport), a cultural leader (e.g. Liverpool John Lennon Airport, Leonardo da Vinci-Fiumicino Airport, Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport) or a prominent figure in aviation history of the region (e.g. Sydney Kingsford Smith Airport), sometimes even famous writers (e.g. Allama Iqbal International Airport) and explorers (e.g. Venice Marco Polo Airport).

Some airports have unofficial names, possibly so widely circulated that its official name is little used or even known.

Some airport names include the word "International" to indicate their ability to handle international air traffic. This includes some airports that do not have scheduled international airline services (e.g. Port Elizabeth International Airport).

History and development

The earliest aircraft takeoff and landing sites were grassy fields.[37] The plane could approach at any angle that provided a favorable wind direction. A slight improvement was the dirt-only field, which eliminated the drag from grass. However, these functioned well only in dry conditions. Later, concrete surfaces would allow landings regardless of meteorological conditions.

The title of "world's oldest airport" is disputed. College Park Airport in Maryland, US, established in 1909 by Wilbur Wright, is generally agreed to be the world's oldest continuously operating airfield,[38] although it serves only general aviation traffic.

Beijing Nanyuan Airport in China, which was built to accommodate planes in 1904, and airships in 1907, opened in 1910.[39] It was in operation until September 2019. Pearson Field Airport in Vancouver, Washington, United States, was built to accommodate planes in 1905 and airships in 1911, and is still in use as of January 2020.

Hamburg Airport opened in January 1911, making it the oldest commercial airport in the world which is still in operation. Bremen Airport opened in 1913 and remains in use, although it served as an American military field between 1945 and 1949. Amsterdam Airport Schiphol opened on September 16, 1916, as a military airfield, but has accepted civil aircraft only since December 17, 1920, allowing Sydney Airport—which started operations in January 1920—to claim to be one of the world's oldest continuously operating commercial airports.[40] Minneapolis-Saint Paul International Airport in the US opened in 1920 and has been in continuous commercial service since. It serves about 35,000,000 passengers each year and continues to expand, recently opening a new 11,000-foot (3,355 m) runway. Of the airports constructed during this early period in aviation, it is one of the largest and busiest that is still currently operating. Rome Ciampino Airport, opened 1916, is also a contender, as well as the Don Mueang International Airport near Bangkok, Thailand, which opened in 1914. Increased aircraft traffic during World War I led to the construction of landing fields. Aircraft had to approach these from certain directions and this led to the development of aids for directing the approach and landing slope.

Following the war, some of these military airfields added civil facilities for handling passenger traffic. One of the earliest such fields was Paris – Le Bourget Airport at Le Bourget, near Paris. The first airport to operate scheduled international commercial services was Hounslow Heath Aerodrome in August 1919, but it was closed and supplanted by Croydon Airport in March 1920.[41] In 1922, the first permanent airport and commercial terminal solely for commercial aviation was opened at Flughafen Devau near what was then Königsberg, East Prussia. The airports of this era used a paved "apron", which permitted night flying as well as landing heavier aircraft.

The first lighting used on an airport was during the latter part of the 1920s; in the 1930s approach lighting came into use. These indicated the proper direction and angle of descent. The colours and flash intervals of these lights became standardized under the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO). In the 1940s, the slope-line approach system was introduced. This consisted of two rows of lights that formed a funnel indicating an aircraft's position on the glideslope. Additional lights indicated incorrect altitude and direction.

After World War II, airport design became more sophisticated. Passenger buildings were being grouped together in an island, with runways arranged in groups about the terminal. This arrangement permitted expansion of the facilities. But it also meant that passengers had to travel further to reach their plane.

An improvement in the landing field was the introduction of grooves in the concrete surface. These run perpendicular to the direction of the landing aircraft and serve to draw off excess rainwater that could build up in front of the plane's wheels.

Airport construction boomed during the 1960s with the increase in jet aircraft traffic. Runways were extended out to 3,000 m (9,800 ft). The fields were constructed out of reinforced concrete using a slip-form machine that produces a continuous slab with no disruptions along the length. The early 1960s also saw the introduction of jet bridge systems to modern airport terminals, an innovation which eliminated outdoor passenger boarding. These systems became commonplace in the United States by the 1970s.

The malicious use of UAVs has led to the deployment of counter unmanned air system (C-UAS) technologies such as the Aaronia AARTOS which have been installed on major international airports.[42][43]

Airports in entertainment

Airports have played major roles in films and television programs due to their very nature as a transport and international hub, and sometimes because of distinctive architectural features of particular airports. One such example of this is The Terminal, a film about a man who becomes permanently grounded in an airport terminal and must survive only on the food and shelter provided by the airport. They are also one of the major elements in movies such as The V.I.P.s, Speed, Airplane!, Airport (1970), Die Hard 2, Soul Plane, Jackie Brown, Get Shorty, Home Alone (1990), Home Alone 2: Lost in New York (1992), Liar Liar, Passenger 57, Final Destination (2000), Unaccompanied Minors, Catch Me If You Can, Rendition and The Langoliers. They have also played important parts in television series like Lost, The Amazing Race, America's Next Top Model (season 10), 90 Day Fiancé, Air Crash Investigation which have significant parts of their story set within airports. In other programmes and films, airports are merely indicative of journeys, e.g. Good Will Hunting.

Several computer simulation games put the player in charge of an airport. These include the Airport Tycoon series, SimAirport and Airport CEO.

Airport directories

Each national aviation authority has a source of information about airports in their country. This will contain information on airport elevation, airport lighting, runway information, communications facilities and frequencies, hours of operation, nearby NAVAIDs and contact information where prior arrangement for landing is necessary.

- Australia

- Information can be found on-line in the En route Supplement Australia (ERSA)[44] which is published by Airservices Australia, a government owned corporation charged with managing Australian ATC.

- Brazil

Infraero is responsible for the airports in Brazil

- Canada

- Two publications, the Canada Flight Supplement (CFS) and the Water Aerodrome Supplement, published by Nav Canada under the authority of Transport Canada provides equivalent information.

- Europe

- The European Organisation for the Safety of Air Navigation (EUROCONTROL) provides an Aeronautical Information Publication (AIP), aeronautical charts and NOTAM services for multiple European countries.

- Germany

- Provided by the Luftfahrt-Bundesamt (Federal Office for Civil Aviation of Germany).

- France

- Aviation Generale Delage edited by Delville and published by Breitling.

- The United Kingdom

- The information is found in Pooley's Flight Guide, a publication compiled with the assistance of the United Kingdom Civil Aviation Authority (CAA). Pooley's also contains information on some continental European airports that are close to Great Britain. National Air Traffic Services, the UK's Air Navigation Service Provider, a public–private partnership also publishes an online AIP for the UK.

- The United States

- The US uses the Airport/Facility Directory (A/FD) (now officially termed the Chart Supplement) published in seven volumes. DAFIF also includes extensive airport data but has been unavailable to the public at large since 2006.

- Japan

- Aeronautical Information Publication (AIP)[45] is provided by Japan Aeronautical Information Service Center, under the authority of Japan Civil Aviation Bureau, Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism of Japan.

A comprehensive, consumer/business directory of commercial airports in the world (primarily for airports as businesses, rather than for pilots) is organized by the trade group Airports Council International.

See also

Lists:

References

- Wragg, D.; Historical dictionary of aviation, History Press 2008.

- "Airport – Definition of airport by Merriam-Webster". Retrieved September 1, 2015.

- "Runway – Definition of runway by Merriam-Webster". Retrieved September 1, 2015.

- "Helipad – Definition of helipad by Merriam-Webster". Retrieved September 1, 2015.

- "Hangar – Definition of hangar by Merriam-Webster". Retrieved September 1, 2015.

- "design8.docx – AIRPORT DEVELOPMENT PAGE NO 1 What is an Airport An airport is an aerodrome with extended facilities mostly for commercial air transport". coursehero.com. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- Canada Flight Supplement. Effective 0901Z 16 July 2020 to 0901Z 10 September 2020.

- 49 U.S.C. § 40102(a) (2012)

- "AirNav: 1ID9 – Skyline Airport". airnav.com. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- "The World Factbook". Retrieved September 1, 2015.

- "The World Factbook". Retrieved September 1, 2015.

- "FAA". Retrieved September 1, 2015.

- "Part 139 Airport Certification". FAA. June 19, 2009. Archived from the original on July 29, 2010. Retrieved July 20, 2010.

- "Airport & Airway Trust Fund (AATF)". faa.gov. Retrieved April 17, 2019.

- Tang, Rachel (January 31, 2017). "The Airport and Airway Trust Fund" (PDF). Congressional Research Service.

- Office, U. S. Government Accountability (May 4, 2005). "Airport and Airway Trust Fund: Preliminary Observations on Past, Present, and Future" (GAO-05-657T). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "How Airports Actually Make Money". Simple Flying. July 21, 2018. Retrieved May 5, 2019.

- "Landing fees". guides.erau.edu.

- Farooqui, Aaryan. "SUMMARY OF AIRPORT CHARGES" (PDF). assest.flysfo.

- "The Current Situation and Change in Airport Revenues: Research on The Europe's Five Busiest Airports".

- "SCHEDULE OF CHARGES FOR AIR TERMINALS John F. Kennedy International Airport" (PDF).

- Read "Guidebook for Managing Small Airports - Second Edition" at NAP.edu.

- "Economy Parking | Chicago O'Hare International Airport (ORD)". www.flychicago.com. Retrieved May 6, 2019.

- Haroon, K. https://www.theairlinepilots.com/forum/viewtopic.php?t=1096. Retrieved April 25, 2020. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Gross, Daniel (September 7, 2017). "Your Misery at the Airport Is Great for Business". Slate. Retrieved September 8, 2017.

- Menno Hubregtse, Wayfinding, Consumption, and Air Terminal Design (London: Routledge, 2020), 44-47.

- USA Today newspaper, October 17, 2006, p. 2D

- "Why do airports have windsocks?". Piggotts Flags And Branding. Retrieved March 29, 2017.

- Mothes, Daphné (January 15, 2019). "Improve your airport maintenance with your CMMS". Mobility Work. Retrieved April 2, 2019.

- Basner, Mathias; Clark, Charlotte; Hansell, Anna; Hileman, James I.; Janssen, Sabine; Shepherd, Kevin; Sparrow, Victor (2017). "Aviation Noise Impacts: State of the Science". Noise & Health. 19 (87): 41–50. doi:10.4103/nah.NAH_104_16 (inactive January 20, 2021). ISSN 1463-1741. PMC 5437751. PMID 29192612.CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2021 (link)

- Sherry, Lance (2009). "Introduction to Airports Design and Operations" (PDF). George Mason University Center for Air Transportation Systems Research.

- Yesudian, Aaron N.; Dawson, Richard J. (January 1, 2021). "Global analysis of sea level rise risk to airports". Climate Risk Management. 31: 100266. doi:10.1016/j.crm.2020.100266. ISSN 2212-0963.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering (October 23, 2019). Airport Greenhouse Gas Reduction Efforts.

- Anurag et al. General Design Procedures for Airport-Based Solar Photovoltaic Systems. Energies 2017, 10(8), 1194; doi:10.3390/en10081194

- "7 cool solar installations at U.S. airports". solarpowerworldonline.com.

- A. Kandt and R. Romero . Implementing Solar Technologies at Airports. NREL Report. Available: https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy14osti/62349.pdf

- Thomas, Andrew R. (2011). Soft Landing: Airline Industry Strategy, Service, and Safety. Apress. p. 154. ISBN 978-1-4302-3677-1.

- "College Park Airport". Pgparks.com. Archived from the original on May 31, 2009. Retrieved July 20, 2010.

- "新京报 - 好新闻,无止境". www.bjnews.com.cn.

- "Sydney Airport history" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on April 1, 2009. Retrieved July 20, 2010.

- Bluffield (2009)

- "Heathrow picks C-UAS to combat drone disruption". Retrieved March 13, 2019.

- "Muscat International Airport to install USD10 million Aaronia counter-UAS system". Retrieved January 21, 2019.

- "En route Supplement Australia (ERSA)". Airservices.gov.au. July 16, 2010. Retrieved July 20, 2010.

- "Aeronautical Information Publication (AIP), NOTAMs in Japan". Japan Civil Aviation Bureau. Archived from [AIS JAPAN - Japan Aeronautical Information Service Center the original] Check

|url=value (help) on July 22, 2011. Retrieved February 14, 2011.

Bibliography

- Ashford, Norman J., Saleh Mumayiz, and Paul H. Wright. (2011) Airport engineering: planning, design, and development of 21st century airports (John Wiley & Sons, 2011).

- Bluffield, Robert. (2009). Imperial Airways – The Birth of the British Airline Industry 1914–1940 ( Ian Allan ISBN 978-1-906537-07-4

- Breidenbach, Philipp. (2020) "Ready for take-off? The economic effects of regional airport expansions in Germany." Regional Studies 54.8 (2020): 1084-1097 online.

- Burghouwt, Guillaume. (2012) Airline network development in Europe and its implications for airport planning (Ashgate, 2012).

- Gillen, David. (2011) "The evolution of airport ownership and governance." Journal of Air Transport Management 17.1 (2011): 3-13, on the evolution of airport governance from public utility to modern business.

- Gordon, Alastair. (2008) Naked Airport: A Cultural History of the World's Most Revolutionary Structure (University of Chicago Press, 2008).

- Halpern, Nigel, and Anne Graham. (2013) Airport marketing (Routledge, 2013).

- Horonjeff, Robert, Francis X. McKelvey, William J. Sproule, and Seth B. Young. (2010) Planning and Design of Airports 5th ed. (McGraw-Hill, 2010).

- Hubregtse, Menno. (2020) Wayfinding, Consumption, and Air Terminal Design (Routledge, 2020).

- Nakamura, Hiroki, and Shunsuke Managi. (2020) "Airport risk of importation and exportation of the COVID-19 pandemic." Transport Policy 96 (2020): 40-47 online.

- Pearman, Hugh. (2004) Airports: A Century of Architecture (Harry N. Abrams, 2004).

- Salter, Mark. 2008. Politics at the Airport (University of Minnesota Press). This book brings together leading scholars to examine how airports both shape and are shaped by current political, social, and economic conditions.

- Sheard, Nicholas. (2019) "Airport size and urban growth." Economica 86.342 (2019): 300-335; In USA, airport size has a positive effect on local employment, with an elasticity of 0.04.

- Wandelt, Sebastian, Xiaoqian Sun, and Jun Zhang. (2019) "Evolution of domestic airport networks: a review and comparative analysis." Transportmetrica B: Transport Dynamics 7.1 (2019): 1-17 online.

External links

- Airport Safety Challenges related to Ground Operations

- "Conquest of Fog" Popular Mechanics, February 1930, illustration and article on a modern airport in the 1930s

- Airport Distance Calculator – Research and Innovative Technology Administration (RITA) in U.S. Department of Transportation

- Map of worldwide airports

- Airport Visualizer Worldwide airports visualized on 30+ maps