Albertine Necker de Saussure

Albertine Adrienne Necker de Saussure (9 April 1766, in Geneva – 13 April 1841, in Mornex,[1] on the Salève, near Geneva) was a Genevan and then Swiss writer and educationalist, and an early advocate of education for women.

Life

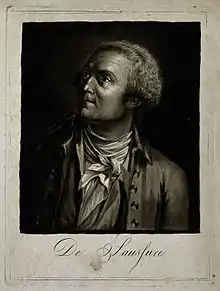

Albertine Necker de Saussure was the daughter of the Genevan scientist Horace-Bénédict de Saussure (1740-1799), a noted physicist, geologist, meteorologist, and Alpine explorer, and Albertine-Amélie Boissier (1745-1817). Horace-Bénédict taught his three children at home, ensuring that they received the best education available at the time. She learned English, German, Italian, and Latin, and her father also trained her in science. She supported her father's schooling in her later writings. Although a Calvinist, her religious views were broadminded and tolerant.

At age 19, Albertine married a noted botanist who was the son of Louis Necker and the nephew and namesake of Louis XVI's finance minister, Jacques Necker.[2] The French Revolution ended Necker's military career and, in 1790, he began teaching as a demonstrator in botany at the l'académie de Genève, a job he had obtained because of his wife's surname.[2] She initially wrote her husband's botany lectures for him, and she educated her own children in a wide range of subjects, including science.[3] They lived in Cologny,[4] and she became a close friend of her husband's cousin, the prominent writer and intellectual Germaine de Staël.[2]

Albertine's brother Nicolas-Théodore de Saussure became a noted chemist and researcher in plant physiology. Additionally, her great uncle Charles Bonnet, like her father, was a famous naturalist.[3]

Albertine did not believe marriage to be the be-all end-all of women's existence, and she did not think that women should be educated solely to please men.[5] She has been compared to Mary Wollstonecraft for believing that single women must maintain themselves through education.[5]

Science

Encouraged by her scientist-father, Horace Bénédict de Saussure, Albertine began, at about age 10, to keep a diary in which she recorded her scientific observations. In time, she became an active experimentalist, and during an attempt to prepare oxygen she burned her face quite badly. As a young woman, she went on geological and botanical expeditions with her father.,[3] but her scientific activity declined after her marriage.[6]

Albertine became acquainted with several well-known scientists of her day.[6] The chemist Louis-Bernard Guyton de Morveau wrote that he had revived her interest in chemistry during a visit in which she stayed with him.[6] Other famous French chemists that she visited included Antoine Lavoisier; Antoine François, comte de Fourcroy; and Claude Louis Berthollet.[6] In a letter to her father, Albertine described experiments she performed in their laboratories.[6]

Written works

Albertine Necker de Saussure's literary work began relatively late in life, after her children were grown.[2] Her principal work, l'Education Progressive or Etude du Cours de la Vie (1828), was a long and influential study of educational theory and the education of women. The work is divided into two parts, originally in three volumes which were published successively.[7] In the first two volumes, in which she examines general education, she follows the child from birth to fourteen years old. The third volume is devoted to the education of women. Albertine believed that women's educational attainments were different from those of men because women did not have the same opportunities as men.[5] She wanted women to fulfill their religious, familial and social obligations, but to do so in a self-possessed manner,[8] and she sought to teach women to be unselfish but also to be able to make independent judgments.[8] Further, she believed that, historically, social attitudes had been harmful to women's dignity and that traces of this remained in women's sense of themselves. She wanted to change this.[8]

Albertine also wrote a biography of her friend Germaine de Staël for the first collected edition of de Staël's works, in 1821.[9] In addition, Albertine authorized a French translation of August Wilhelm Schlegel's Vorlesungen über dramatische Kunst und Literatur (1809-1811).[10]

Legacy

Albertine Necker de Saussure's work l'Education Progressive is acknowledged as an educational classic and was influential in nineteenth-century England.[11] She was active in the Groupe de Coppet, a salon that flourished between the French Revolution and the early years of the Restoration,[2] and she has been credited with spreading the spirit of the Coppet to a new generation of Genevese aristocrats, including Adolphe Pictet.[2] The portrait of Albertine sitting next to her knitting basket is considered a most appropriate symbol of a late Enlightenment Genevoise.[7]

Albertine Necker de Saussure is one of 999 notable women whose names are inscribed on the Heritage Floor in Judy Chicago's installation piece The Dinner Party at the Brooklyn Museum, New York.[12]

Family

She married Jacques Necker (1757-1825), Professor of Botany at the University of Geneva. Their son was the crystallographer and geologist Louis Albert Necker de Saussure HFRSE FGS (1786-1861).[13]

Notes

- Dictionnaire historique de la Suisse

- Joseph, John E. Saussure (1st ed.). Oxford, U.K: Oxford University Press. pp. 33–38. ISBN 9780199695652.

- Sheffield, Suzanne Le-May (2004). Women and Science Social Impact and Interaction. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. pp. 93–94. ISBN 1851094652.

- Dictionnaire historique de la Suisse

- Montgomery, edited by Fiona; Collette, Christine (2001). The European women's history reader (1st ed.). London: Routledge. p. 50. ISBN 0415220815.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Rayner-Canham, Marelene Rayner-Canham; Geoffrey (1998). Women in chemistry : their changing roles from alchemical times to the mid-twentieth century. Washington, DC: American Chemical Society. p. 24. ISBN 0841235228.

- Monter, E. William (1980). "Women in Calvinist Geneva (1550-1800)". Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society. 6 (2): 206. doi:10.1086/493792. S2CID 145777230.

- Montgomery, edited by Fiona; Collette, Christine (2001). The European women's history reader (1st ed.). London: Routledge. pp. 72–74. ISBN 0415220815.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Les Oeuvres completes de Madame la Baronne de Stael, publiees par son Fils. Precedees d'une notice sur le caractere et les ecrits de Madame de Stael, par Madame Necker de Saussure. Paris, 17 vols. 8vo. and 17 vols. in 12mo.)

- Rosa, George M (1994). "Byron, Mme de Staël, Schlegel, and the Religious Motif in Armance". Comparative Literature. 46 (4): 346–371. doi:10.2307/1771377. JSTOR 1771377.

- Hans, Nicholas (1967). "Educational relations of Geneva and England in the eighteenth century". British Journal of Educational Studies. 15 (3): 268. doi:10.2307/3119457. JSTOR 3119457.

- "Albertine Necker de Saussure". Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art: The Dinner Party: Heritage Floor: Albertine Necker de Saussure. Brooklyn Museum. 2007. Retrieved 24 October 2016.

- Biographical Index of Former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783–2002 (PDF). The Royal Society of Edinburgh. July 2006. ISBN 0-902-198-84-X.

References

- Encyclopædia Britannica: Albertine-Adrienne Necker de Saussure

- Necker de Saussure at The New Dictionary of Education – (Translation) Accessed May 2007