Alexander Kugel

Alexander Rafailovich Kugel (Russian: Александр Рафаилович Кугель, born Avraam Rafailovich Kugel; 26 August [O.S. 14 August] 1869 1864, — 5 October 1928) was a Russian and Soviet theatre critic and editor, founder of the False Mirror (Krivoye Zerkalo), a popular theatre of parodies.[1][2]

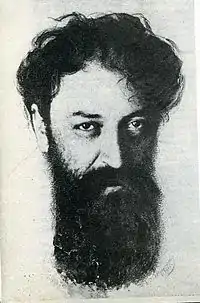

Alexander Kugel | |

|---|---|

Portrait by P. Lebedinsky, 1915 | |

| Born | Avraam Rafailovich Kugel August 26, 1864 |

| Died | October 5, 1928 (aged 64) Leningrad, USSR |

| Occupation | theatre critic and entrepreneur, dramatist, memoirist |

| Years active | 1886-1928 |

| Spouse(s) | Zinaida Kholmskaya |

Biography

Alexander Kugel was born in Mazyr, in the Minsk Governorate of the Russian Empire (present-day Belarus), to rabbi Rafail Mikhaylovich Kugel and his wife Balbana Yakovlevna. Both his parents were respected figures: his father founded the first printing-house in the city; his mother launched the Russian school for Jewish children in Mozyr. Alexander had two brothers, Iona and Nathan, who later became journalists.[3]

In 1886, after graduating from Saint Petersburg University, where he studied law, Kugel started to contribute feuilletons and theatre reviews for the newspapers Peterburgskaya Gazeta, Rus and Den, using the pseudonyms "Homo Novus", "N. Negorev" and "Kvidam".[1] Some of those were later included in his books Untitled (Без заглавия, 1890), Under the Auspice of the Constitution (Под сенью конституции, 1907) and Theatrical Portraits (Театральные портреты, 1923).

In 1897 he started editing the magazine Teatr i Iskusstvo, an illustrated weekly, which soon became the most influential, authoritative and intellectual publication dealing with theatre in Russia.[4] Among the publications that came out as supplements to the magazine were The People of Theatre Dictionary (Словарь сценических деятелей, 1898–1916, 16 issues, letters А—М), and compilations of plays, theatre memoirs and music scores.[5]

A staunch 'starover' in all questions concerning the theatre, Kugel launched a personal crusade against 'symbolism, decadence and all manner of theatrical fable-telling', believing them to have "nothing to do with either art or [Russian] national tradition," according to the Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary.[2] Fighting for what he saw as the 'actor's right to express his individuality on stage', he decried the 'director's dictatorship', which renders the actor "a faceless puppet, dancing to somebody else's tune,"[5] and soon became the major detractor of all the leading Russian theatre directors, most of all Konstantin Stanislavski and Vsevolod Meyerhold.[6] "Stanislavski, always tetchy about bad reviews, initially treated the critic as a personal enemy, but soon learned to value Kugel's insightful analyses of his directorial schemes and ideas, and even admire this 'useful' opponent," according to the theatre historian Inna Solovyova.[2]

Another of Kugel's theories proposed that "literature should either serve theatre or step aside." For Kugel Griboyedov's Woe from Wit was a fine pamphlet but poor material for stage production, and all of Pushkin's plays, barring Boris Godunov, while being indisputable works of genius, were 'un-stageable' and "have brought very little to the theatre."[3] The "perfect marriage of literature and theatre" for him was represented only by the works of William Shakespeare and Alexander Ostrovsky.[3]

He panned Leo Tolstoy's The Power of Darkness as 'too literary', and in Chekhov's Three Sisters recognised nothing but 'deadly hopelessness.'[3] Olga Knipper-Chekhova, engaged as Ranevskaya in The Cherry Orchard, wrote to Chekhov: "Kugel was telling us yesterday that the play was wonderful, everybody performed fine, but not what they were supposed to. He thinks that what we do is play vaudeville instead of tragedy, as you'd intended, and that we totally mis-interpreted Chekhov."[3] "Did Kugel indeed say the play was good? Think I'd rather send him 1/4 pound of tea and a pound of sugar, to keep him in benign moods," Chekhov wrote her in reply. Still, the "Moscow Art Theatre had no greater enemy than Kugel," Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko maintained.[3]

In 1908 Kugel and his wife, the actress Zinaida Kholmskaya, co-founded the False Mirror (Krivoye Zerkalo), originally a night cabaret, then, after Nikolai Evreinov's arrival as a director, a popular theatre of parodies. He remained the head of it until 1918, and then led it again, after it re-opened, in 1922-1928.[1]

Kugel considered himself as belonging to Russian culture but had strong views on the situation of the Jews in the country, and never hesitated before making them heard. In the early 1900s he criticised what he saw as Russian government-incited antisemitism and, speaking at the Second Russian Theatre Congress, launched an attack on the actress Polina Strepetova, who had demanded that Jewish actors should be re-settled beyond the pale.[5] One of the founders of the Jewish Theatrical Society in 1917, he championed what he saw as the 'purity of Jewish national art' and, within that framework, expressed skepticism about at least two productions of the Habima Theatre, the Evgeny Vakhtangov-directed production of The Dybbuk by S. Ansky, and The Wandering Jew directed by Vakhtang Mchedelov.[5]

In 1917-1918, outraged by the October Revolution (as well as by the fact that both his magazine and his theatre got shut down), Kugel lost all interest in theatre and became one of the most consistent critics of the Bolshevik regime.[2] This led to his being arrested and incarcerated. He was extricated, although not by Maria Andreyeva (to whom his relatives rushed for help and who, remembering his feuds with Maxim Gorky, maintained that never in her live had she 'ever heard of such a person, Kugel'), but by the Bolshevik minister of culture Anatoly Lunacharsky, who personally arrived to fetch him out of jail, and later told the Cheka leaders to 'leave that man alone'.[3]

In 1926, commemorating the centenary of the Decembrist revolt, the Moscow Art Theatre staged Kugel's play Nicholas the First and the Decembrists, the dramatised take on Dmitry Merezhkovsky's novels, Alexander the First and December 14. The production (a risky adventure, bearing in mind Merezhkovsky's strong anti-Bolshevist stance in France) marked a kind of 'peace treaty'. In 1927 Stanislavsky met Kugel in Kislovodsk. "Now he is old, very ill and apparently before his death wants to patch up things of the past. So the past was exactly what we've not spoken a word about," Stanislavsky wrote in his diary.[7]

Back in the early 1910s Kugel planned to release a series of books showcasing his theories and beliefs, but first came the First World War, then the 1917 Revolutions, and only one of the planned publications came out, in 1923, Endorsement of Theatre (Утверждение театра). He authored two books of memoirs, Literary Memoirs. 1882—1896) (1923) and Leaves off a Tree. Memoirs (1926, dealing with the 1896—1908 period). In 1927 his monograph on Vasily Kachalov was released. Two more books of his, Profiles of the Theatre and Russian Dramatists, came out posthumously.[2]

Alexander Kugel died on 5 October 1928 in Leningrad. He is interred in Volkovo Cemetery.[3]

References

- "Александр Рафаилович Кугель". Russian Biographical Dictionary // Биографический словарь. 2000. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- Alexander Kugel. The biography at the Moscow Art Theatre site

- "Alexander Kugel biography". Alef Magazine. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- Alexander Kugel. Saint Petersburg University. Famous Graduates. Law Faculty // Анисимов. Знаменитые студенты Санкт-Петербургского университета. Юридический факультет. Санкт-Петербургский государственный университет, юридический факультет. — СПб, 2012. - 344 с., 2012. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- Александр Рафаилович Кугель. Biography at eleven.co.il

- Shabalina, Tatyana. Кривое зеркало // Distorting Mirror Theatre at the Krugosvet On-line Encyclopedia

- "...Tеперь он стар, сильно болен и, должно быть, перед смертью хочет загладить прошлое. О нем мы, конечно, ничего не говорили, ни слова". К. С. Станиславский, Собрание сочинений, т.8, с.160