Alfred Cortot

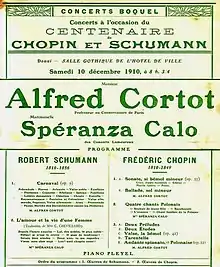

Alfred Denis Cortot (also Cortôt, French-European spelling) (pronounced [core-TOE]) (26 September 1877 – 15 June 1962) was a French pianist, conductor, and teacher who was one of the most renowned classical musicians of the 20th century. He was especially valued for his poetic insight into Romantic piano works, particularly those of Chopin, Saint-Saëns and Schumann.[1]

Alfred Cortot | |

|---|---|

| |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Alfred Denis Cortot |

| Born | 26 September 1877 Nyon, Vaud, Switzerland |

| Died | 15 June 1962 (aged 84) Lausanne, Vaud, Switzerland |

| Genres | Classical music |

| Occupation(s) | Pianist, conductor |

| Instruments | Piano |

Early life and education

Cortot was born in Nyon, Vaud, in the French-speaking part of Switzerland, to a French father and a Swiss mother. His first cousin was the composer Edgard Varèse.[2] He studied at the Paris Conservatoire with Émile Decombes (a student of Frédéric Chopin), and with Louis Diémer, taking a premier prix in 1896. He made his debut at the Concerts Colonne in 1897, playing Beethoven's Piano Concerto No. 3.

Between 1898 and 1901 he was a choral coach and subsequently an assistant conductor at the Bayreuth Festival. In 1902 he conducted the Paris premiere of Wagner's Götterdämmerung. He formed a concert society to perform Wagner's Parsifal, Beethoven's Missa solemnis, Brahms' German Requiem, and new works by French composers.

Career

In 1905, Cortot formed a trio with Jacques Thibaud and Pablo Casals, which established itself as the leading piano trio of its era. In 1907, he was appointed Professor by Gabriel Fauré at the Conservatoire de Paris, replacing Raoul Pugno. He continued to teach at the Paris Conservatoire until 1923, where his pupils included Yvonne Lefébure, Vlado Perlemuter, Simone Plé-Caussade, Magdeleine Brard, and Marguerite Monnot.

In 1919, Cortot founded the École Normale de Musique de Paris. His courses in musical interpretation were legendary. For his many notable students, see here.

As a leading musical figure, Cortot traveled for many international music events. The French government sponsored two promotional tours to the United States and one to the Soviet Union in 1920. He conducted several orchestras and was often called upon to provide piano accompaniment for touring artists when in Paris. He was involved in music until his health failed, and taught master classes in piano in his advanced years.

On 21 March 1925, Cortot made the world's first commercial electrical recording of classical music for the Victor Talking Machine Company in Camden, New Jersey: Chopin's Impromptus and Schubert's Litanei, issued on Victor's Red Seal label.[3]

World War II

During World War II, he accepted the position of Haut-Commissaire ("High Commissioner") for arts in the Vichy government and served twice (1941 and 1942) as a member of the Vichy's Conseil national ("National Council").[4][5][6]. However, before this he took a strong stance in defending the French music tradition with the Beaux Arts administration (Fine Arts) supporting soldiers with music.[7] Cortot had to leave this position after Pétain appointment and exerted his energy instead into writing reports about cultural propaganda and defending French musical styles. He was charged with musical reform by the Pétain government, and the Vichy took control of musical activities. He became part of the comité d’organisation professionelle de la musique (The committee for the professional organisation of music) in 1942 and worked with Laval and Pétain.[7]

In 1941 he participated in a Propaganda Staffel (Propaganda Squad) festival in Paris, and in 1942 played with Wilhelm Kempff for Nazi artist Arno Breker's art exposition, later meeting with Brecker at Paul Morand's home. Pierre Laval was also present. Mornad had a statue made of Cortot after his impression.[7] He participated in official concerts in Paris during the occupation as well as in Germany in 1942.[4]

Daisy Fancourt writes, " Indeed, in February 1943 Cortot had argued that musicians should not take part in the Service du travail obligatoire (Compulsory work service) introduced by Hitler, as it might compromise their future musical career. He had also called for musical prisoners to be able to join German orchestras. In May 1943 he had even succeeded in liberating twenty musician prisoners. His work extended to fighting in favour of Jewish musicians, such as the Polish soprano Marya Freund: after she was arrested in 1944 and moved to Drancy, Cortot helped to get her transferred to a hospital where she survived and escaped. Cortot was also not French, but Swiss, and claimed never to have felt the same nationalistic sentiment towards France that caused many other French musicians to flee the Nazis and emigrate to the US. He was married (although estranged) to a woman of Jewish origin, and was friends with Jewish intellectuals such as Leon Blum, the first Jewish Prime Minister of France."[7]

After the war's conclusion, Cortot was found guilty by a French government panel of collaboration with the enemy and was suspended from performing for a year.,[8] He said in his defence, "I’ve given 50 years of my life to the helping the French cause [...] when I was asked to become involved with the interests of my comrades, I felt I couldn’t refuse. [...] I represented the interests of the French government less than the interests of France. [...] I have never been involved in politics."[7] Once the suspension expired he returned to performing more than 100 concerts a season.[5]

Death

Cortot died on 15 June 1962, aged 84, of uremia from kidney failure in Lausanne, Switzerland.[1]

Contribution

As one of the most celebrated piano interpreters of Chopin, Schumann and Debussy, Cortot produced printed editions of the piano works of all three, notable for their inclusion of meticulous commentary on technical problems and matters of interpretation.[9]

Cortot suffered from memory lapses in concert (particularly notable from the 1940s onwards) and often left wrong notes on his later records.[10] When in form, however, he showed a brilliant technique that could handle almost any kind of pianistic firework. This gift is evident in his legendary recordings of Liszt's Sonata in B minor (the first recording ever made of this masterwork) and Saint-Saëns' Etude en forme de valse. The latter thoroughly impressed even Vladimir Horowitz, who - according to Cortot - approached Cortot to learn his "secret" in performing it; Cortot, however, did not divulge it to him.[11] He recorded more of Chopin than of any other composer, and his performances of Chopin's Piano Concerto No. 2 in F minor with conductor Sir John Barbirolli and Saint-Saëns' Piano Concerto No. 4 in C minor under Charles Munch, both originally issued on RCA Victor/HMV 78s but reissued on CD in the Naxos Historical series (among others) rank among the all-time great concerto recordings.

He also wrote a good deal of didactic prose, including a piano primer: Rational Principles of Pianoforte Technique. This book contains many finger exercises to aid in the development of various aspects of piano playing technique. It was originally written in French but has long since been translated into other languages.

Technical flaws notwithstanding, Cortot was among the very greatest musicians of the century, and his recordings and musical annotations have seldom been out of print.

In the 1920s, Cortot recorded a number of piano rolls for the Aeolian/Duo-Art company, since 78-rpm records were not always satisfactory in quality or maximum duration of the recording. Once he performed a Liszt Rhapsody weaving his own playing live at the piano with its mechanical reproduction. With eyes closed, some critics could not distinguish between the two. Cortot also made many recordings, the last in 1957, five years before his death. In addition to his recordings of works by Chopin, Schumann, and Liszt, he also made important recordings of music by Weber, Mendelssohn, Franck, Debussy and others, and conducted his Ecole Normale orchestra (with a full nineteenth-century string complement) in a complete recording of the Brandenburg Concertos for RCA Victor in the early 1930s, in which he performed the lengthy solo cadenza of No. 5 in D major, on a modern piano in the grand Romantic manner yet exceedingly effectively in that admittedly archaic style, ending in a grand ritardando and rolled concluding D major chord as the orchestra re-entered with the concluding ritornello. He is also famous for his several trio recordings with Jacques Thibaud and Pablo Casals. Less famously but more appropriately and exquisitely styled, he accompanied singers such as Maggie Teyte and Charles Panzéra. There is even a late recording of Schumann's Dichterliebe in which he accompanied Gerard Souzay, of which the singer said, laconically, 'He was too old, and I was too young'. His final, postwar solo recordings are marred by more frequent technical slips, but he retained his uniquely eloquent phrasing and the free, Romantic performing manner for which he was famous.

Other notable pupils of Cortot during his later years included Samson François, Esteban Sánchez, and Chris Mary Francine Whittle.Translator Barbara Wright also studied under Cortot in the 1930s.

Bibliography

- Cortot, Alfred, La musique française de piano, 1930–48

- —, Cours d’interprétation, 1934 (Studies in Musical Interpretation, 1937)

- —, Aspects de Chopin, 1949 (In Search of Chopin, 1951)

Notes

- "Alfred Cortot, Pianist, Is Dead. Soloist and Conductor, 84, Backed Vichy Regime". The New York Times. 16 June 1962.

- Varèse, Edgard; Jolivet, André (2002). Jolivet-Erlih, Christine, ed. Correspondance 1931–1965 (in French). Contrechamps. p. 110

- 40,000 Years of Music: Man in Search of Music - 144 Jacques Chailley - 1964 "On March 21st, 1925, Alfred Cortot made for the Victor Co., in Camden, New Jersey, the first classical recording to employ a new technique, thanks to which the gramophone was to play an important part in musical life: electric ..."

- 'Alfred Denis Cortot', The Fryderyk Chopin Institut, accessed 13 January 2018.

- David Dubal booklet to Nimbus Records release of Duo-Art piano rolls "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 18 April 2008.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- France The Dark Years 1940–1944 by Julian T. Jackson, published in 2003 by Oxford University Press

- "Music and the Holocaust: Cortot, Alfred". holocaustmusic.ort.org. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- Chimènes, Myriam, 'Alfred Cortot et la politique musicale du gouvernement de Vichy' in La vie musicale sous Vichy, ed Chimènes (2001) ISBN 2 87027 864 0 , reviewed by Nigel Simeone, Musical Times, Vol. 142, No. 1876 (2001)

- "Category:Cortot, Alfred/Editor".

- "ALFRED CORTOT".

- STUART ISACOFF (28 November 2005). "The Master Speaks ... and Plays". The New York Sun.

References

- Gavoty, Bernard, Alfred Cortot, 1977 (French)

- Manshardt, Thomas, Aspects of Cortot, 1994

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Alfred Cortot |

- Guide to Alfred Cortot Collection, 1491-1853 housed at the University of Kentucky Libraries Special Collections Research Center

- Recordings