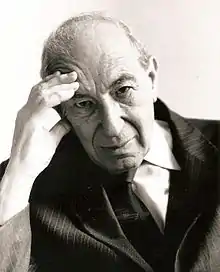

Alfred Reynolds (writer)

Alfred Reynolds (born Reinhold Alfréd; 13 December 1907, Budapest – 1993, London[1]) was a writer on social and religious topics. He is known in Hungary principally as a poet and for his publication of poems by Miklós Radnóti and others in the 1930s, and in England for his leadership of the Bridge Circle, post-1945.

Biography

Reynolds was born into a wealthy family in Budapest, of a Jewish mother and a Roman Catholic father. He was educated at schools in Budapest and Vienna and at the University of Leipzig (1928–1931).[1] In 1931 he founded the literary magazine Haladás (Progress), in which he published the poets Miklós Radnóti, István Vas and Mihály-András Rónai. The police forced him to close the magazine, but then he started a left-leaning monthly, Névtelen Jegyző (Anonymous Chronicler), which published his only collection of poetry, Első és utolsó lírai kötete (First and Last Book of Lyrics) (1932)[2] before it too was closed down. Reynolds briefly joined the Communist Party of Hungary, leaving after the assassination of Sergey Kirov in 1934, allegedly ordered by Joseph Stalin. He was imprisoned, subsequently placed under police observation and lost his job. In 1936 he escaped from Hungary and went to London where he lived for the rest of his life. He was in the British Army during the Second World War and joined the Intelligence Corps in 1944, participating in the denazification programme, see below.

In post-war London Reynolds led a libertarian group called the Bridge Circle.[3] Articles from its journal, the London Letter, are collected in Pilate's Question (1982), the title essay of which was the group's central focus of attention.[4] Writers who early in their careers attended Bridge Circle meetings included Sidney E. Parker, Nicolas Walter, Bill Hopkins and Stuart Holroyd. Most notable was Colin Wilson, who has said he first wrote The Outsider as a riposte to Pilate's Question.

Reynolds' Jesus versus Christianity (1988) contrasts the teachings of Jesus with the doctrines of the Christian churches.[5]

Reynolds had been known of in Hungarian literary circles because of his friendship with the youthful Radnóti but he had little contact with Hungarian writers after moving to England. In 1980 a copy of his early volume of poetry was rediscovered by the literary critic François Bréda in a bookshop in Cluj-Napoca, Romania, and he was traced in London. In 1993 he visited Cluj at the invitation of Bréda and the poet Géza Szőcs, where he was well received[6] and donated to Szőcs some hitherto unreleased Radnóti manuscripts.[7]

Reynolds' archive comprises: family photographs dating from the mid nineteenth century; literary & political works; letters; photographs, letters, art work and ephemera from his time during and after World War II working in the denazification programme with German prisoners of war at Kempton Park in England and Slemdal Camp in Norway.

The wartime archive has been donated to the UK's Imperial War Museum at Duxford, near Cambridge.[8] (Catalogue Number: Documents.23619). Correspondence with Martin Buber has been donated to the National Museum of Israel in Jerusalem.[9]

All other publications, papers, photographs and letters together with copies of the items at Duxford and Jerusalem have been donated to the Petőfi Literary Museum in Budapest. The archive was in the possession of the late Dr. Alan Detweiler who was delighted that his great friend's archive and published works had found a home in Hungary.[10]

Works

- Reinhold Alfréd, Első és utolsó lírai kötete, Névtelen Jegyző kiadása, Budapest, 1932. (in Hungarian)

- Alfred Reynolds, The Hidden Years. Introduction by Colin Wilson. Cambridge International Publishers, London, 1981.

- Alfred Reynolds, Pilate's Question. Twenty years of articles, essays and sketches (1950–1970). Cambridge International Publishers, London, 1982.

- Alfred Reynolds, Jesus Versus Christianity. Open Gate Press, 393 p., 1988, 1993.

Bibliography

- Bréda Ferenc, "Jószerencsét", Fátum-úr...(Kicsoda ön, Reinhold Alfréd ?!...). In : Igazság. Fellegvár, 83. szám, Cluj-Napoca, 4 October 1980 (Vö. Volt egyszer egy Fellegvár. Összeállította Martos Gábor. Erdélyi Híradó Könyv- és Lapkiadó, 1994, Cluj-Napoca, p. 78., p. 100.)

- Szőcs Géza, Reinholdról . In : Igazság. Fellegvár, 83. szám, Cluj-Napoca, 1980. okt. 4. (Vö. Volt egyszer egy Fellegvár. Összeállította Martos Gábor. Erdélyi Híradó Könyv- és Lapkiadó, 1994, Cluj-Napocavár, p. 78., p. 100.)

- Bréda Ferenc, Eső a Fellegváron avagy Reinhold Alfréd első útja Kolozsvárra. In : Helikon, Cluj-Napoca, 24/ 1993, p. 6.

- Bréda Ferenc, << Alfréd halála után >>... In : Szabadság, Cluj-Napoca, 17 June 1994, Campus-melléklet

- Szőcs Géza, Kicsoda ön, Reinhold Alfréd ? In : Helikon, Cluj-Napoca, 24/ 1993, p. 6.

- Márton Ibolya, Reinhold-interjú, 1993, Cluj-Napoca. In : Echinox, Cluj-Napoca, 1993/ 9, p. 14.

- Richard Headicar, Reinhold Alfréd, Colchester, Animata Omnia, 2004.

- Nicolas Walter, Anarchism in Print : Yesterday and Today, Government and Opposition, 5:4, pp. 523–540, 1970.

Online texts

References

- Richard Headicar, Reinhold Alfred, Colchester: Animata Omnia, 2004

- Reinhold Alfréd, Első és utolsó lírai kötete, Budapest: Névtelen Jegyző, 1932

- Nicolas Walter, "Anarchism in Print: Yesterday and Today", Government and Opposition, 5:4, pp. 523-540, 1970

- Alfred Reynolds, Pilate's Question: Twenty years of articles, essays and sketches (1950-1970), London: Cambridge International Publishers, 1982

- Alfred Reynolds, Jesus Versus Christianity, Open Gate Press, 1993

- "François Bréda". Archived from the original on 11 September 2011. Retrieved 8 August 2010.

- François Bréda, Alfréd Halála Után (Hungarian)

- Link to Catalogue Entry for Documents.23619

- National Library of Israel, Jerusalem.

Search Martin Buber letters & Reynolds for entry. - Obituary of Alan Gregory Detweiler, Toronto Globe and Mail, 10 March 2012

External links

- Alfred Reynolds - Reinhold Alfréd, Facebook (in Hungarian and French)

- [Tristan Ranx, Nanochevik] (in French)