Alice Hawkins

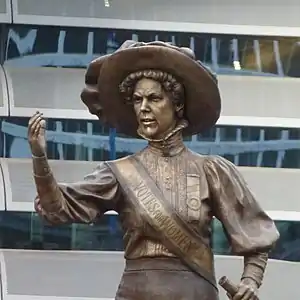

Alice Hawkins (Stafford, 1863 – Leicester, 1946) was a leading English suffragette among the boot and shoe machinists of Leicester. She went to prison five times for acts committed as part of the Women’s Social and Political Union militant campaign.[1][2][3] Her husband Alfred Hawkins was also an active suffragist and received £100 when his kneecap was fractured as he was ejected from a meeting in Bradford. In 2018 a statue of Alice was unveiled in Leicester Market Square.

Alice Hawkins | |

|---|---|

Alice Hawkins selling "Votes for Women" | |

| Born | 1863 Stafford, Staffordshire, England |

| Died | 1946 Leicester, Leicestershire, England |

| Nationality | British |

| Occupation | Boot and shoe machinist |

| Known for | Leading suffragette in Leicester |

| Spouse(s) | Alfred Hawkins |

| Children | six |

Life

Hawkins was born in 1863 in Stafford and by 13 she was working in Leicester creating boots and shoes. In 1884 she married Alfred Hawkins.[4] She was a mother of six children and worked as a machinist at Equity Shoes. In 1896 she joined the new factory's new Women's Co-operative Guild where she learnt about socialism and the writings of Thomas Mann.[4][3] Hawkins had joined the Independent Labour Party in 1894 and via that organisation met Sylvia Pankhurst. Pankhurst came to Leicester in 1907 and Hawkins made introductions. They were soon joined by Mary Gawthorpe and they established a WSPU presence in Leicester.[4]

Hawkins was first jailed in February 1907, among 29 women sent to Holloway Prison after a march on Parliament. After two weeks in jail she returned to Leicester to set up a branch of the WSPU. Alice was jailed a second time in 1909 as she tried to force entry into a public meeting where Winston Churchill was speaking in Leicester. In this case the lead role was played by her husband, Alfred. Alice could not gain access into the room where Churchill was speaking so Alfred volunteered. During the speech Alfred asked Churchill to explain why women did not have a vote and he was ejected. Alice was protesting outside when she too was arrested.[5]

Alfred also defended Alice when heckled by men in a crowd where she was speaking saying 'get back to your family!" She was able to say 'here is my family they are here to support me" as Alfred was demonstrably for the cause, [6] which some but not by any means all suffragists could claim. Alfred suffered for his support, when he was eventually awarded £100 compensation after having his leg broken during a suffragette protest on 26 November 1910. His case had been taken up by the Men's Political Union for Women's Enfranchisement after he was thrown down some stairs after protesting against Winston Churchill during a Liberal party meeting Bradford. The judge ruled that he had been ejected without warning after merely asking a question and that was an assault.[5]

Her third imprisonment was in 1911 after throwing a brick through a Home Office window in full view of a policeman. She was jailed twice more in 1913, first for throwing ink into a Leicester post box, and then a last time for digging a slogan into a golf course at night.[7][8] She received a Hunger Strike Medal from the WSPU. Hawkins was one of the prisoners who built a relationship with the female prison warders also working-class women who comforted the prisoners as well as having the job of holding them down to be force-fed.[9]

In 1913 Hawkins was among the representatives chosen to speak with leading politicians David Lloyd George and Sir Edward Grey. The meeting had been arranged by Annie Kenney and Flora Drummond with the proviso that these were working-class women representing their class. They explained the terrible pay and working conditions that they suffered and their hope that a vote would enable women to challenge the status quo in a democratic manner. Hawkins explained how her fellow male workers could choose a man to represent them whilst the women were left unrepresented.[10][6]

Her protests ceased when war was declared in 1914 and the WSPU agreed to cease protests in exchange for having all prisoners released. Home Office report that 1,300 women were arrested over the years in this cause, along with 100 men like Alice Hawkins' husband Alfred.[6]

Death and legacy

Hawkins died in 1946 and her burial had to be paid for by the state, a 'pauper's grave'. [6] She has a plaque at her workplace and another on the Leicester Walk of Fame. In 2018, a five-year campaign ended when a seven foot high statue was unveiled in market square by four women including Manjula Sood and Liz Kendall. The ceremony was witnessed by Helen Pankhurst, dozens of her relatives and hundreds of people.[11]

Her great-grandson, Peter Barratt speaks to schools and at public events, a century later, that Hawkins was fighting for women to have equal pay and that is still not achieved, and encouraging all people to use their right to vote. He found the transcript in the National Archives of the delegation including Hawkins of Working Women to Lloyd George, the chancellor, from January 1913.[6]

Other sources

- Alice Hawkins: And the Suffragette Movement in Edwardian Leicester, 2007[12]

- Tejera, P. (2018). Reinas de la carretera. Madrid. Ediciones Casiopea.

References

- Frank Meeres Suffragettes: How Britain’s Women Fought & Died for the Right to Vote 2013 144562057X They included Alice Hawkins, who worked among the boot and shoemakers in Leicester,

- Ned Newitt A People's History of Leicester: A Pictorial History of Working ... 2008 Women's Suffrage Alice Hawkins ( 1863-1946) was one of Leicester's leading suffragettes. She went to prison five times for various acts committed as part of the WSPU's militant campaign for the vote. Mrs Hawkins was a mother of five children and worked as a machinist at Equity Shoes. She had been active in the ILP and in 1910 became president of the breakaway Independent National Union of Boot and Women Shoe Workers. Alice Hawkins on her way to prison in July 1913, ...

- Elizabeth Crawford The Women's Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide 1866-1928 2003 1135434026 "She lived for a time at Cradley Heath with the women chainmakers, before moving to Leicester, where she lived with Alice Hawkins and painted women shoemakers. She then travelled to Wigan to study women "pit brow" workers and, from there, back down to Staffordshire to the potteries and then onto Scarborough, on the east coast, to paint the Scottish fishwives who followed the herring fleet.

- Elizabeth Crawford (2 September 2003). The Women's Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide 1866-1928. Routledge. pp. 281–. ISBN 1-135-43402-6.

- "Alice Hawkins Suffragette, the History of Women's Rights - Alice's Life". www.alicesuffragette.co.uk. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- Peck, Sally (2018-02-05). "My great-grandfather was a suffragette, too". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 2019-11-08.

- Daily Mirror Oct 2015 My ancestor was just a poor factory worker but she fought for women's rights "Suffragette, which stars Carey Mulligan as fictional washerwoman Maud Watts also stars Kate Barratt whose great great grandmother was a real Suffragette"

- BBC 24 January 2018 Suffragette Alice Hawkins' family praise Leicester statue

- "The Suffragettes and Holloway prison". Museum of London. Retrieved 2019-11-07.

- "Let's not forget the working class suffragettes". www.newstatesman.com. Retrieved Jan 5, 2021.

- Martin, Dan (2018-02-03). "Watch 7ft statue of suffragette Alice Hawkins being installed". leicestermercury. Retrieved 2018-02-04.

- Richard Whitmore (2007). Alice Hawkins: And the Suffragette Movement in Edwardian Leicester. Breedon. ISBN 978-1-85983-554-8.