Alternative theories of the location of Great Moravia

Alternative theories of the location of Great Moravia propose that the core territory of "Great Moravia", a 9th-century Slavic polity, was not (or was only partly) located in the region of the northern Morava River (in present-day Czech Republic). Moravia emerged after the fall of the Avar Khaganate in the early 9th century. It flourished during the reign of Svatopluk I in the second half of the century, but collapsed in the first decade of the 10th century. "Great Moravia" was regarded as an archetype of Czechoslovakia, the common state of the Czechs and Slovaks, in the 20th century, and its legacy is mentioned in the preamble to the Constitution of Slovakia.

Several aspects of its history (including its territorial extension and political status) are the subject of scholarly disputes. A debate about the location of its core territory began in the second half of the 20th century.[1] Imre Boba proposed that the center of Moravia was located near the southern Morava River (in present-day Serbia). Most specialists (including Herwig Wolfram and Florin Curta) rejected Boba's theory, but it was further developed by other historians, including Charles Bowlus and Martin Eggers. In addition to the theory of a "southern Moravia", new theories were proposed, arguing for the existence of two Moravias, called "Greater and Lesser Moravia", or arguing that the center of Moravia was at the confluence of the rivers Tisza and Mureș. Archaeological evidence does not support the alternative theories, because the existence of 9th-century power centers can only be documented along the northern Morava River, in accordance with the traditional view. However, scholars who accept the traditional view of a "northern Moravia" have not fully explained some of the contradictions between the written sources and archaeological evidence. For instance, written sources suggest a southward movement of the armies when mentioning the invasion of Moravia from the Duchy of Bavaria.

Great Moravia

The Moravians emerged as an individual Slavic tribe after the fall of the Avar Khaganate in the early 9th century.[2] The first reference to them was recorded in the year 822 AD in the Royal Frankish Annals.[3][4] More than a century later, the Byzantine Emperor Constantine Porphyrogenitus mentioned their realm as "Megale Moravia", or "Great Moravia".[4][5] The name, which is not mentioned in other primary sources, has been interpreted in various way. "Megale" may refer either to a territory which was located "further away" from Constantinople or to a former polity that had disappeared by the middle of the 10th century.[4][5]

The first known Moravian ruler, Mojmir I, assisted the rebellious subjects of Louis the German, the King of East Francia, several times.[6] During his reign, priests came from the Bishopric of Passau (a suffragan of the Archbishopric of Salzburg) to proselytize among the Moravians.[7] Louis the German expelled Mojmir from Moravia in 846.[6] In an attempt to diminish the influence of the German clerics, Mojmir's nephew and successor, Rastislav, requested priests from the Byzantine Empire in the early 860s.[8][7] Emperor Michael III and Patriarch Photius sent two brothers, Saints Cyril and Methodius, to Moravia.[8] The brothers started to translate liturgical texts into Old Church Slavonic in Moravia.[9] Methodius, who survived his brother, was consecrated as archbishop by Pope Hadrian II in Rome in 869.[7] Under the pope's decision, Moravia, the realm of Rastislav's nephew, Svatopluk, and the Pannonian domains of Koceľ fell within Methodius's jurisdiction, which caused conflicts with the archbishops of Salzburg.[10]

Louis the German occupied Moravia and dethroned Rastislav, and the Bavarian prelates imprisoned Methodius in 870.[8] Svatopluk united his realm with Moravia around 871 and expanded the territory under his rule during the next decades.[11][12] Methodius was set free on Pope John VIII's demand in 873.[13] However, after his death in 885, his disciples were expelled from Moravia.[14] Svatopluk died in 894.[15] His realm disintegrated because internal conflicts emerged after his death.[15] The Magyars who settled in the Carpathian Basin around 895 destroyed Moravia in the first decade of 10th century.[15]

Development of alternative theories

The systematic study of the history of Moravia began in the 19th century, influenced by the ideas of Romanticism and Pan-Slavism.[16] Scholarly discussions have also been colored by political debates for centuries.[17] After the establishment of Czechoslovakia in 1918, "Great Moravia" was regarded as an archetype of the common state of the Czechs and Slovaks.[16][18] The Czechoslovak delegates referred to it when arguing for the recognition of the new state.[19] In 1963, official celebrations of the eleventh centenary of the mission of Constantine and Methodius in Czechoslovakia emphasized the continuity between the early medieval state and its modern successor.[18] A reference to "Great Moravia" can be found in the preamble to both the 1948 Constitution of the Czechoslovak Republic and the 1992 Constitution of Slovakia.[17]

Several aspects of the history of Moravia are subjects of scholarly debate.[1] Most modern scholars question earlier historians' descriptions of a "Great Moravian empire" with huge territories permanently integrated within it.[4][12] Studies published from the 1990s also dispute the argument that Moravia reached the level of an early medieval state (a lasting and stable polity) during its history.[20]

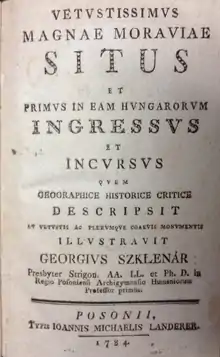

According to the traditional view, Moravia's core territory was located along the northern Morava River, a tributary of the Danube in present-day Czech Republic.[21] Juraj Sklenár, an 18th-century Slovak historian, was the first to propose an alternative location; he argued that Moravia had originally been centered around Sirmium (now Sremska Mitrovica in Serbia), from where it expanded to the north to the lands that now form the Czech Republic and Slovakia.[22] In 1813 Slovene philologist Jernej Kopitar elaborated this hypothesis proposing that Moravia actually was the name of a city.[23] Nine years later Austrian historian Friedrich Blumberger supported the theory, polemicizing with Josef Dobrovský, a stanch opponent of the theory, over the original dates of the Cyril and Methodius veneration in the territory of modern Czechia and Slovakia[24] and over the course of this dispute he reiterated Kopitar's arguments that Moravia should have been a city.[25] After the death of Dobrovský in 1829 the dispute naturally ceased, and the theory was forgotten for more than a century; Italian linguist Sergio Bonazza argued in 2008 that this was caused by the fact that an influential Croatian Slavic scholar Vatroslav Jagić, a supporter of the conventional theory and the publisher of Kopitar–Dobrovský correspondence, harshly criticized the former, omissed most of his arguments from the historical monograph Istoriya slavyanskoy filologii (History of Slavic Philology) and mentioned Blumberger only in the context of Dobrovský's claim that he was Kopitar's assumed name.[26]

Imre Boba was the first historian in the 20th century to challenge the traditional view.[5] After studying the primary sources, he concluded that Moravia's core territory lay near the southern Morava River, around Sirmium.[5][21] He published his theory in a monograph (Moravia's History Reconsidered: A Reinterpretation of Medieval Sources) in 1971.[5] Most Central European historians (including Herwig Wolfram, Josef Poulík and István Bóna) rejected his argument, but other scholars, including Charles Bowlus and Martin Eggers, developed them further in the 1990s.[8][27][28][4] According to Florin Curta, who does not support the alternative theories, Bowlus has written the "most elegant presentation" of their argumentation.[29] Scholars who support the traditional boundaries argue that no archaeological evidence substantiates the existence of a 9th-century power center in the lands where the alternative theories suggest Moravia's core region would have been.[6][30][31] On the other hand, excavations proved that important centers of power existed at Mikulčice, Pohansko and other settlements north of the Middle Danube in the 9th century[6][31][32] as it was predicted by the traditional view.

Michael McCornick says that Boba and his followers generated a "healthy debate".[8] Curta emphasizes that the location of Moravia "may be understandably viewed as a matter of nationalist concern", because of "a quite recent history of shifting political frontiers" in Central Europe.[18] He also writes that "a hostile, rather than critical, attitude towards Boba's ideas became the norm among Slovak historians" in the early 1990s.[33] Vincent Sedlák, a Slovak historian, argues that Boba developed his theory "to deny the historical validity of Slovak territory"; Curta writes that this is not a baseless statement.[34] Most arguments of Boba and his followers have been "effectively countered", but the "interpretation of the written evidence provided by the Frankish sources continues to be debated", according to Nora Berend, Przemyslaw Urbańczyk and Przemyslaw Wiszewski.[4] Jiří Macháček, also an opponent to the alternative theories, argues that "the serious problems of geographical orientation raised by analysis of the written sources, which ultimately led Imre Boba and his followers to question the traditional location of Great Moravia, will have to be explained in some other way."[35] However, he also says, the alternative theories have been demonstrated to be a non-perspective branch of research and they are not accepted by the international scientific community.[36][note 1] According to Roger Collins, the dispute about Moravia's location "remains to be resolved"; he also argues that archaeological evidence should not be overemphasized against written sources.[37]

Southern Moravia of Juraj Sklenár

In 1784, Juraj Sklenár, a Slovak historian and teacher of rhetoric in Pressburg (today's Bratislava), published Vetustissumus magnae Moravie situs et primus in eam Hungarorum ingressus et incursus (English: The oldest location of Great Moravia and the first invasion and the arrival of the Hungarians into it). His work had a political purpose and character.[38] He argued that the Magyars never conquered the territory inhabited by the Slovaks and the latter voluntarily joined the Kingdom of Hungary during the rule of Ladislaus I of Hungary.[39][38]

Sklenár associated (Great) Moravians with the Slavs who settled near the Morava River in Moesia and adopted the name Moravians. Sklenár supported his claim by the work of the Russian chronicler Nestor.[40] Sklenár argued that Old Moravia was located not only in Moesia but also in Pannonia. He supported this argument with the writings of Constantine VII and especially his work De administrando imperio, which placed Great Moravia in the territory between Trajan's Bridge, Sirmium (today's Sremska Mitrovica) and Belgrade. Sklenár also used Frankish sources and cited Methodius's appointment as bishop of Pannonia. Sklenár argued that the original territory of Mojmír I was in the south, on the border of Moesia and Pannonia, and that Pribina's Nitrava (a different city from modern-day Nitra) was also on this border. He suggests that Mojmír expelled Pribina from Nitrava and that Pribina then crossed the Sava river and settled in lower Pannonia. Old Moravia then expanded to include Dacia. He suggested that the location of Great Moravia in the territories of modern-day Moravia and Slovakia was to be explained by further expansion to the west and that the territory between the Morava and Hron rivers (western and central Slovakia) would have been ruled by Czechs and Bohemians and that it should be called Bohemia or Magna Chroatia (Great Croatia). He used a letter from Bavarian bishops – who mentioned Pagan tribes subjugated by Svatopluk and forced to adopt Christianity – to argue that the region was conquered by Svatopluk and that "Czech Moravia" was joined to Great Moravia only in 890 (along with Bohemia) after the agreement between Svatopluk and Arnulf of Carinthia.[41] Similar opinions were sustained by Gheorghe Şincai a Romanian historian of the 18th century [42]

Sklenár's theory was questioned by István Katona, a prominent Hungarian historian. This led to intensive scientific dispute, not least because Sklenár questioned the reliability of an anonymous chronicle that was one of the key sources for contemporary historiography. The dispute was followed with interest both in Moravia and Bohemia. Sklenár's arguments and the dispute were well known to prominent Slavists like Josef Dobrovský or Pavel Jozef Šafárik,[43] but his theory did not find support among Slovak, Czech, Moravian or Hungarian historians.

Southern Moravia of Imre Boba

According to Boba's theory, Moravia was not an independent state north of the Middle Danube, but a principality, located in Pannonia, within a larger state, "Sclavonia".[44] Sclavonia, he argued, developed between the Adriatic Sea and the Drava River after the fall of the Avar Khaganate.[45] Most Latin and Slavic names of the Principality of Moravia[note 2] and its inhabitants[note 3] show that it was named after a town, called "Margus" or "Marava".[45] Priscus a late-Roman scholar, mentioned a city named "Margus" on the southern Morava river (also called "Margus" in antiquity).[46][47]

Boba says that the realm of Liudewit, a rebellious Slavic prince in Pannonia, obviously included Moravia.[45] The first reference to the Moravians (their homage to Louis the German in Frankfurt)[48] was recorded for the year of Liudewit's expulsion from his seat by the Franks (822).[45] The rulers of the Sclavonian principalities made several attempts to achieve an independent position.[45] Svatopluk closely cooperated with the Holy See to increase his autonomy.[45] He conquered the region of the northern Morava river and expanded his authority over Bohemia in 890.[49]

Frankish sources

According to Boba, geographical references in the Annals of Fulda also show that Moravia was located to the south of the Danube.[50] For instance, the annals recorded that Louis the German's army moved ultra Danuvium ("across the Danube" or "over the Danube") when he invaded Moravia in 864, suggesting a southward movement across the Danube towards Moravia from the perspective of the Fulda Abbey (which stood in a land to the north of the river).[51] The same source also mentioned that the retainers of Arn, Bishop of Würzburg, ambushed a group of Moravian Slavs on their way back to Moravia from Bohemia, implying that the Moravians moved to the south or southeast (instead of moving towards the northern Morava River) when returning from Bohemia.[52][53] Florin Curta, who does not accept Boba's analysis, says that the Annals of Fulda, written in a distant monastery, can hardly be regarded as a reliable source of information about the geography of Central Europe.[50]

Boba also says that the comparison of different records of the same historical event concerning Moravia also suggest that Moravia was located in Pannonia.[54] For instance, the Magyars destroyed Pannonia (according to the Annals of Fulda) or Moravia (according to Regino of Prüm) in 894, implying that Pannonia and Moravia were one and the same territory.[54]

| Annals of Fulda | Regino of Prüm |

|---|---|

| Zwentibald, the dux of the Moravians and the source of all treachery, who had disturbed all the lands around him with tricks and cunning and circled around thirsting for human blood, made an unhappy end, exhorting his men at the last that they should not be lovers of peace but rather continue in enmity with their neighbors. The Avars, who are called Hungarians, penetrated across the Danube at this time, and did many terrible things. They killed men and old women outright, and carried off the young women alone with them like cattle to satisfy their lusts, and reduced the whole Pannonia to a desert. In the autumn peace was made between the Bavarians and the Moravians.[55] |

Also around this time Zwentibald king of the Moravian Slavs, a man most prudent among his people and very cunning by nature, ended his final day. His sons held his kingdom for a short and unhappy time, because the Hungarians utterly destroyed everything in it.[56] |

Byzantine texts

Emperor Constantine VII mentioned "great Moravia" four times in his De administrando imperio.[57] According to his catalogue of the peoples that were the neighbors of the Hungarians, "great Moravia, the country of Sphendoplokos"[58][note 4] was located to the south of the Principality of Hungary.[59][57] When listing the "landmarks and names along the Danube river", Constantine stated that "great Moravia, the unbaptized ... over which in former days Sphendoplokus used to rule."[60] lay beyond Trajan's Bridge, Sirmium and Belgrade.[61] According to Boba, all descriptions show that Constantine thought that Moravia had been situated in the wider region of Trajan's Bridge (in present-day Drobeta-Turnu Severin in Romania), Belgrade and Sirmium.[61] The Hungarian historian Sándor László Tóth says that Constantine, who knew that the Hungarians had occupied Moravia, most probably described Moravia based on his information of the Hungarians' land around 950, instead of using earlier sources.[62]

Florin Curta says that primary sources show that Moravia could not be located in the region of Sirmium.[63] The Life of Methodius recorded that the "koroljъ ugrъrъsk came to the lands of the Danube"[64] and Methodius went to see him.[63][65] According to Curta, the episode refers to a meeting between a "Magyar king" and Methodius during Methodius's journey to or from the Byzantine Empire in 881 or 882. This would make the southern location of Moravia impossible, because Methodius would not have approached the region of the Lower Danube (dominated by the Magyars in the 880s) if he had travelled between Sirmium and Constantinople.[63] Many scholars (including Marvin Kantor, the translator of the Life of Methodius) say that the koroljъ ugrъrъsk was actually Emperor Charles the Fat; if their interpretation is valid, Methodius met the emperor in East Francia.[65] According to Curta, the Life of St. Clement of Ohrid, a hagiography attributed to Theophylact of Ohrid who died in 1126, suggests that Methodius's three disciples, Clement, Naum and Angelarius, approached the Danube from the north before crossing the river at Belgrade during their flight from Moravia to the Byzantine Empire after Methodius's death.[63]

Methodius's see

Pope John VIII's letters identify Methodius's ecclesiastic province as diocesis Pannonica.[66][67] The Life of Methodius also state that Methodius was "consecrated to the bishopric of Pannonia, to the seat of Saint Andronicus, an Apostle of the seventy".[68][69][70] If Methodius was ordained bishop in accordance with the canons adopted at previous synods, he must have been consecrated to a cathedral in a town and could not be moved from his episcopal see, according to Boba.[71] For instance, the Council of Chalcedon decreed in 451 that "No one ... who belongs to the ecclesiastical order, is to be ordained without title, unless the one ordained is specially assigned to a city or village church or to a martyr's shrine or a monastery".[71]

Maddalena Betti says that Boba's argumentation, which is based on canons from the 4th and 5th centuries, is "problematic".[72] Methodius's career followed the pattern set up for earlier medieval missionaries, including Willibrord-Clement and Wynfrith-Boniface.[73] Wynfrith-Boniface started his missions as a simple priest; he was then ordained a missionary bishop for the "people of Germany and to those east of the river Rhine", but his see was not specified; finally, he received a pallium in token of his right to organize a new ecclesiastical province.[74] She argues that, in a similar fashion, Methodius returned from Rome to the domains of Koceľ as a simple monk, that he was subsequently consecrated as a missionary bishop and that, finally, he received a pallium.[75]

According to Boba, Latin and Old Church Slavonic records of Methodius's title[note 5] show that he was ordained archbishop of the see in a town called Maraba or Morava.[76] Boba associated Maraba or Morava with Sirmium, because Sirmium was the capital of the Roman province of Pannonia Secunda.[76] To prove that Methodius had a fixed see, Boba suggested that a medieval church, excavated in Mačvanska Mitrovica in 1966, was identical with Methodius's cathedral.[77] V. Popović, an archaeologist, soon refuted the identification, demonstrating that the church was built in the 11th century.[77]

The Forgeries of Lorch (a collection of papal documents forged for Piligrim, who was Bishop of Passau between 971 and 991) also contain references to Moravia.[78] The documents show that late-10th-century clerics in Passau thought that Moravia had been located in Upper Pannonia and Moesia a century earlier.[78][79] According to Alexandru Madgearu, a Romanian historian, Piligrim's forgeries prove that, by the time they were completed, the location of the former Roman province of Moesia had been forgotten and the clerics who completed the forgeries applied its name to Moravia.[80]

According to Maddalena Betti, Alfred the Great's translation of Orosius's History of the World, which was completed in the late 9th century, prove that Moravia was located to the north of the Danube.[81] Alfred the Great listed the "Thyringas", "Behemas", the "half of the Begware" and the "land of the Vistula" among the neighbors of the "Maroara".[81] Betti also notes that Constantine and Methodius crossed the Pannonian domains of Koceľ while travelling from Moravia to Venice, according to the Life of Constantine, which also shows that Moravia most plausibly lay north of Koceľ's domains.[82]

Medieval chronicles

The Supetar Cartulary, which was compiled in the 12th century, contains a list of the predecessors of Zvonimir, King of Croatia, which begins with "Sventopolk".[83][84] The late 12th-century Chronicle of the Priest of Duklja wrote of Sventopelk, the son of a certain Svetimir, who was descended from one Ratimir.[85][86] According to the same source, "Constantine the Philosopher" crossed Sventopelk's realm when travelling from Bulgaria to Rome.[85][86] The source also recorded that Sventopelk was crowned king "on the field of Dalma".[85][86] The Chronica Ragusina Junii Restii (a chronicle written in the Republic of Ragusa) stated that Svetopelek's father, Svetimir had been the King of Bosnia.[83][87] Two later annals from Ragusa (now Dubrovnik in Croatia) referred to a king from a Moravian-Croatian dynasty.[83][87] Boba and Bowlus associated Ratimir with Ratimir, Duke of Lower Pannonia and Sventopelk with Svatopluk I of Moravia.[85][86] According to Boba and Bowlus, these sources clearly associate Moravia with Dalmatia and Bosnia.[87] Markus Osterrieder describes Boba as "shockingly uncritical" in accepting the Chronicle of the Priest of Duklja as a reliable source.[88] Betti argues that the later sources did not describe the political situation of the 9th-century Balkan Peninsula, because they were written to "support the political needs of subsequent centuries".[89]

Two Moravias

Péter Püspöki-Nagy proposed the existence of two Moravias: a "Great" Moravia at the southern Morava river in present-day Serbia, and another Moravia on the northern Morava river in present-day Czech Republic.[90] Toru Senga, a Japanese historian living in Hungary, likewise concludes that two polities named Moravia co-existed in the 9th century and were united under Svatopluk I.[91] Before unification, the first (Rastislav's) Moravia was located in present-day Czech Republic. The second (Svatopluk's) Moravia was in present-day Hungary between Danube and Tisa and neighboured with Bulgars not only in the east but also in the north (present-day Slovakia).[92] Again, none of these theories achieved wider acceptance in the academic community, particularly among European historians.[93] Critical reactions came also from the Hungarian scholars (György Györffy, Csanád Bálint).[94]

Moravia east of the Tisza

In 1995, German historian Martin Eggers published his dissertation "Das Großmährische Reich" Realität oder Fiktion? ("Great Moravian Empire" – reality or fiction?). According to Eggers, the Avars played an important role in the territories north of the Danube also after the fall of the Avar Khaganate. Similarly to Toru's and Püspöki Nagy's view, Eggers also backs up the hypothesis of two Moravias, however he places both entities in the Southeast.[1]

Eggers says that the Moravian tribe (Moravljane) came to the east of the Carpathian Basin after the fall of the khaganate. Present-day Slovakia should be inhabited by "remnant Avar groups" (Vulgarii – Bulgars) up to territories settled by the Vistulans in present-day Poland[note 6] and the archaeological findings in Moravia were attributed by him to some "ethnic group with the Avar tradition".[95] Egger's Moravians helped to defend the Frankish Empire against attacks from the east and they later founded their own domain around center near the confluence of the rivers Tisza and Mureș at present-day Cenad in Romania.[96][97] These Moravians were closely connected to other southern Slavs and shared a common material culture (Bijelo Brdo culture). They were connected also personally, because Mojmir, Rastislav and Svatopluk had origin in the same Bosnian-Slavonian dynasty. Also in this theory, the author questioned the location of the Pribina's Nitrava which might not be the same place as Slovak Nitra.[95] While Rastislav ruled this southern Moravia, Svatopluk was a Bosnian-Slavonian ruler. In 871, Svatopluk came to power in Cenad and both principalities were unified under his leadership. This become a basis for a large but short-lived empire which lasted only for one generation. Svatopluk expanded his influence to Croatia (879), took control over present-day Slovakia (874–880), joined Panonia (884) and received his crown during a formal ceremony (885). In 890, Arnulf donated him Bohemia,[98] which had already close ties to (Czech) Moravia.[95] Only after the fall of the Great Moravia, the name was transferred to the north and a false awareness about its history began to spread.

Eggers' work was published by prestigious publisher and thus raised also larger critical reactions of central European historians and archaeologists.[99][100][101][102] Herwig Wolfram, Director of the Austrian Institute for Historical Research, who had an early access to his dissertation work not available yet to other experts, immediately pointed to some problems related to Egger's interpretation of written sources. [103] According to his opinion, historians should rely mainly on such sources which are close to events in time and space (which was not fulfilled in Eggers's work) and he confirmed traditional localization. Several critics noticed that Eggers references to unpublished part of his work or studies which only have to be published in the future.[104][105][106] Like Boba and others, Eggers again depends to a large extent on Chronicle of the Priest of Duklja, a source known for numerous fictions and inaccuracies.[107] Bijelo Brdo culture is dated to more than one hundred years later than it was assumed by him. A theory about remnant Avar groups in Slovakia in the second half of the 9th century is not based on any archeological research[108] and earlier Avar settlements are documented only in the southernmost part of Slovakia.[108][109][110] Marsina criticizes Eggers' approach as unreliable and unscientific, stating that his theory contradicted not only the state of research in the 1990s, but research of the Avar settlements in Slovakia since the 1950s. In this regard, Třeštík notices also incompatibility with written sources, the trial to locate Vulgarii who "had only 5 castles" (see Bavarian Geographer), they were numerous people and had not a custom to build castles clearly describes (according to him) situation in the Bulgar Khaganate and not present-day Slovakia.[104] In the case of Bohemia, Eggers conceals mention about an occupation of Bohemia by Svatopluk by force which could pose several problems for his theory, according to Třeštík.[111][note 7] Eggers' view on early relationship between Bohemia and Moravia is unusual, especially for a German historian. Bohemia should control Moravia, but none comparable power centers have been found in Bohemia at the time.[112] The archaeological research suggests that the earliest Bohemian hillforts were inspired by Moravian and not the other way around.[112][note 8]

On the other hand, Eggers's work received some support from Horace Lunt who was not a historian, but a linguist and philologist.[113] He writes that "Close and open minded study of the remarkably limited primary sources inevitably reveals that crucial structural elements of the intricate traditional construct are pure guesswork. What held it all together was the dogmatic authority of generations of scholars; to accept the dogma is to demonstrate "right" thinking".[114] Likewise, John B. Freed says that he is inclined to accept Egger's (and Bowlus's) "arguments for a southern Moravia because such a location provides a better explanation for the East Frankish military structure and the Cyrillo-Methodian mission".[115] However, he also admits that he is not a specialist of the history of the late Carolingian period.[115]

See also

Notes

- Macháček associates rejection of these theories by the scientific community with their poor quality. Macháček as a director of research laboratory of the Masaryk University at Břeclav-Pohansko notices also regular participation of international teams on archeological research, in the last years mainly experts from USA, Germany and Austria.

- For instance, regnum Marahensium (Latin), and Moravskaia oblast (Old Church Slavonic).[45]

- Including, Sclavi Marahenses (Latin), and Moravliene (Old Church Slavonic).[45]

- That is, Svatopluk I of Moravia

- Pope John VIII referred to Methodius as archiepiscopus sanctae ecclesiae Marabensis in 880. The Life of Methodius mentioned him as arkhiepiskoup Moravska.

- See also "Karte 18: Die Großreichsbildung unter Sventopulk und seine Entwicklung 870–894".

- According to Třeštík, the conquest of Bohemia by Svatopluk could open several unwanted issues. Eggers has to explain how did Svatopluk conquer Bohemia, what was his goal and how could he keep the territory from the south. Instead of addressing these issues, Eggers assumed that Bohemia was donated to Svatopluk by Arnulf. Třeštík claims that such voluntary donation is absurd, because Arnulf would open the way to his own Bavaria and leave the eastern territories unprotected. He also states that it is absurd to believe that Bohemians would agree with such "gift". Arnulf could donate only what he really held – a formal, hegemonic claim on the territory and not the real ownership. In such case, Bohemia should be controlled with the help of Frankish dukes as it is known from Carathania and Moravia. So, Eggers cites only Regino's chronicle and conceals a mention from Annales Fuldenses about a conquest by force. Another problem is Bořivoj's baptism during Svatopluk's rule in Bohemia, because in 890 he was already dead.

- Compare also: "The idea that Bořivoj ruled rich and prestigious Moravian centers and their inhabitants worn in silk and gold from his primitive stronghold in Levý Hradec seems to be a little bit funny for me." Třeštík 1996, p. 91

References

- Szymczak 2010, p. 293.

- Štih 2010, pp. 99, 131.

- Štih 2010, p. 131.

- Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, p. 57.

- Macháček 2009, p. 261.

- Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, p. 58.

- Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, p. 60.

- McCornick 2001, p. 189.

- Curta 2006, p. 125.

- Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, p. 61.

- Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, p. 59.

- Barford 2001, p. 110.

- McCornick 2001, p. 193.

- McCornick 2001, pp. 195–196.

- Barford 2001, p. 111.

- Macháček 2012, p. 7.

- Macháček 2012, p. 6.

- Curta 2009, p. 239.

- Macháček 2012, p. 5.

- Macháček 2012, pp. 9–11.

- Curta 2006, pp. 127–128.

- Marsina 2000, p. 156.

- Kopitar, Bartholomäus; Miklosich, Franz Ritter von (1857). Barth. Kopitars Kleinere Schriften: Sprachwissenschaftlichen, geschichtlichen, ethnographischen und rechtshistorischen Inhalts (in German). F. Beck. p. 166.

- Jahrbücher der Literatur (in German). Gerold. 1824. p. 220.

- Jahrbücher der Literatur (in German). Gerold. 1827. p. 71.

- Bonazza, Sergio (2008). "Wie neu ist Imre Bobas neue Interpretation der Geschichte Mährens?" [How new is Imre Boba's new interpretation of the history of Moravia?]. Welt der Slaven (in German). 53 (1): 161–173.

- Macháček 2009, pp. 261–262.

- Tóth 1999, p. 25.

- Curta 2006, p. 128 (note 40).

- Curta 2009, pp. 132–133.

- Macháček 2009, p. 264.

- Curta 2009, pp. 130–131.

- Curta 2009, p. 244.

- Curta 2009, p. 240.

- Macháček 2009, p. 265.

- Macháček 2014.

- Collins 2010, p. 402.

- Meřínský 2006, p. 743.

- Tibenský 1958, pp. 100, 103.

- Tibenský 1958.

- Tibenský 1958, p. 100.

- Şincai 1969, p. 255.

- Šafařík 1863, p. 507.

- Boba 1971, p. 26.

- Boba 1971, p. 6.

- Boba 1971, p. 35.

- Bowlus 1994, p. 183.

- Bowlus 1994, p. 92.

- Boba 1971, p. 62.

- Curta 2006, p. 128.

- Boba 1971, pp. 42–43.

- Boba 1971, p. 49.

- Bowlus 1994, pp. 176–177.

- Boba 1971, p. 66.

- The Annals of Fulda (year 894), p. 129.

- The Chronicle of Regino of Prüm (year 894), p. 418.

- Tóth 1999, p. 26.

- Constantine Porphyrogenitus: De Administrando Imperio (ch. 13), p. 65.

- Boba 1971, p. 76.

- Constantine Porphyrogenitus: De Administrando Imperio (ch. 40), p. 177.

- Boba 1971, p. 79.

- Tóth 1999, pp. 26–27.

- Curta 2006, p. 129.

- The Life of Methodius (ch. 16.), p. 125.

- Bowlus 1994, pp. 214–215.

- Boba 1971, p. 88.

- Betti 2013, p. 149.

- The Life of Methodius (ch. 8.), p. 117.

- Boba 1971, p. 92.

- Betti 2013, p. 69.

- Boba 1971, p. 87.

- Betti 2013, p. 30.

- Betti 2013, pp. 172–173.

- Betti 2013, pp. 153, 174–175, 178–179.

- Betti 2013, pp. 171–173.

- Boba 1971, pp. 91–92, 95.

- Betti 2013, p. 32.

- Boba 1971, p. 10.

- Bowlus 1994, p. 8.

- Madgearu 2013, p. 98.

- Betti 2013, p. 145.

- Betti 2013, pp. 144–145.

- Boba 1971, p. 107.

- Bowlus 1994, pp. 189–190.

- Bowlus 1994, p. 189.

- Boba 1971, p. 105.

- Bowlus 1994, p. 190.

- Osterrieder 1997, p. 117.

- Betti 2013, p. 29.

- Püspöki-Nagy 1978, pp. 60–82.

- Senga 1983, pp. 307–345.

- Senga 1982, p. 535.

- Marsina 1995, p. 9.

- Štefanovičová 2000, p. 6.

- Eggers 1995.

- Bowlus 2009, p. 313.

- Macháček 2009, p. 262.

- Eggers 1995, p. 286.

- Wolfram 1995.

- Mühle 1997.

- Třeštík 1996.

- Bláhová 1996.

- Wolfram 1995, pp. 3–15.

- Třeštík 1996, p. 88.

- Marsina 1999, p. 32.

- Mühle 1997, p. 218.

- Třeštík 1996, p. 87.

- Marsina 2000, p. 163.

- Zábojník 2004, p. 10.

- Odler 2012, p. 50.

- Třeštík 1996, p. 91.

- Macháček 2009, p. 263.

- Lunt 1996, p. 947.

- Lunt 1996, p. 946.

- Freed 1997, p. 92.

Sources

Primary sources

- Constantine Porphyrogenitus: De Administrando Imperio (Greek text edited by Gyula Moravcsik, English translation by Romillyi J. H. Jenkins) (1967). Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies. ISBN 0-88402-021-5.

- The Annals of Fulda (Ninth-Century Histories, Volume II) (Translated and annotated by Timothy Reuter) (1992). Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-3458-2.

- The Chronicle of Regino of Prüm (2009). In: History and Politics in Late Carolingian and Ottonian Europe: The Chronicle of Regino of Prüm and Adalbert of Magdeburg (Translated and annotated by Simon MacLean); Manchester University Press; ISBN 978-0-7190-7135-5.

- "The Life of Methodius" (1983). In Medieval Slavic Lives of Saints and Princes (Marvin Kantor) [Michigan Slavic Translation 5]. University of Michigan. pp. 97–138. ISBN 0-930042-44-1.

Secondary sources

- Barford, P. M. (2001). The Early Slavs: Culture and Society in Early Medieval Eastern Europe. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-3977-9.

- Berend, Nora; Urbańczyk, Przemysław; Wiszewski, Przemysław (2013). Central Europe in the High Middle Ages: Bohemia, Hungary and Poland, c. 900-c. 1300. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-78156-5.

- Betti, Maddalena (2013). The Making of Christian Moravia (858–882): Papal Power and Political Reality. Brill. pp. 27–34. ISBN 978-90-04-26008-5.

- Bláhová, Marie (1996). "Das Großmährische Reich – Realität oder Fiction? [recension]". Ostbairische Grenzmarken. 38 (1).

- Boba, Imre (1971). Moravia's History Reconsidered: A Reinterpretation of Medieval Sources. Martinus Nijhoff. ISBN 978-90-247-5041-2.

- Bowlus, Charles R. (1994). Franks, Moravians and Magyars: The Struggle for the Middle Danube, 788–907. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-3276-3.

- Bowlus, Charles R. (2009). "Nitra: when did it become a part of the Moravian realm? Evidence in the Frankish sources". Early Medieval Europe. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 17 (3): 311–328. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0254.2009.00279.x.

- Collins, Roger (2010). Early Medieval Europe, 300–1000. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-01428-3.

- Curta, Florin (2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89452-4.

- Curta, Florin (2009). "The history and archaeology of Great Moravia: an introduction". Early Medieval Europe. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 17 (3): 248–267. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0254.2009.00275.x. Retrieved 2015-09-08.

- Freed, John B. (1997). "Review: Das Großmährische Reich" – Realität oder Fiktion?: eine Neuinterpretation der Quellen zur Geschichte des mittleren Donauraumes im 9. Jahrhundert, Stuttgart by Martin Eggers". Central European History. Cambridge University Press. 30 (1): 89–92. doi:10.1017/s0008938900013388. ISSN 0008-9389.

- Lunt, Horace G. (1996). "Review: Das Großmährische Reich" – Realität oder Fiktion?: eine Neuinterpretation der Quellen zur Geschichte des mittleren Donauraumes im 9. Jahrhundert, Stuttgart by Martin Eggers". Speculum. Medieval Academy of America. 71 (4). ISSN 0038-7134.

- Macháček, Jiří (2009). "Disputes over Great Moravia: chiefdom or state? the Morava or the Tisza River?". Early Medieval Europe. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 17 (3): 248–267. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0254.2009.00276.x. Retrieved 2013-08-30.

- Macháček, Jiří (2012). ""Great Moravian state"–a controversy in Central European medieval studies". Studia Slavica et Balcanica Petropolitana. Publishing House of the History Department of the Saint-Petersburg State University. 11 (1): 5–26. Retrieved 2015-09-08.

- Macháček, Jiří (2014). "Vystavěla si Velká Morava svůj věhlas na obchodu s otroky?". Věda pro život (in Czech). Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-10-25.

- Madgearu, Alexandru (2013). Byzantine Military Organization on the Danube, 10th–12th Centuries. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-21243-5.

- Marsina, Richard (1995). Nové pohľady historickej vedy na Slovenské dejiny. 1. Najstaršie obdobie slovenských dejín (do prelomu 9.-10. storočia) (in Slovak). Bratislava: Metodické centrum mesta Bratislavy. ISBN 80-7164-069-7.

- Marsina, Richard (2000). "Where was Great Moravia?". In Kováč, Dušan (ed.). Slovak Contributions to 19th International Congress of Historical Sciences. VEDA, Vydavateľstvo Slovenskej akadémie vied. ISBN 80-224-0665-1.

- Meřínský, Zdeněk (2006). České země od příchodu Slovanů po Velkou Moravu II [The Czech Lands since the arrival of the Slavs to Great Moravia] (in Czech). Libry. ISBN 80-7277-105-1.

- McCornick, Michael (2001). Origins of the European Economy: Communications and Commerce, AD 300–900. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-66102-1.

- Mühle, Eduard (1997). "Altmähren oder Moravia?". Zeitschrift für Ostmitteleuropa-Forschung (in German). Marburg: Herder-Institut für historische Ostmitteleuropaforschung. 47 (2). ISSN 0948-8294.

- Odler, Martin (2012). "Avarské sídliská v strednej Európe: problémová bilancia" [Avar Settlements in Central Europe: the Balance of the Problem]. In Klápště, Jan (ed.). Studia mediaevalia Pragensia 11 (in Slovak). Praha: Univerzita Karlova v Praze – Nakladatelství Karolinum. ISBN 978-80-246-2107-4.

- Osterrieder, Markus (1997). "Das Grossmährische Reich: Zwei Neue Studien". Bohemia. 37: 112–119.

- Püspöki-Nagy, Péter (1978). "Nagymorávia fekvéséről" [On the location of Great Moravia]. Valóság (in Hungarian). Tudományos Ismeretterjesztő Társulat. XXI (11): 60–82.

- Šafařík, Pavel Josef (1863). Sebrané spisy Pavla Jos. Šafaříka, Díl II. Starožitnosti slovanské okresu druhého (in Czech). Praha: Temský.

- Senga, Toru (1982). "La situation géographique de la Grande-Moravie et les Hongrois conquérants" [The geographical location of Great Moravia and the Hungarian conquerors]. Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas (in French). Franz Steiner Verlag. 30 (4). ISSN 0021-4019.

- Senga, Toru (1983). "Morávia bukása és a honfoglaló magyarok" [The fall of Moravia and the Hungarians occupying the Carpathian Basin]. Századok (in Hungarian). Magyar Történelmi Társulat (2): 307–345.

- Şincai, Gheorghe (1969). "Hronica românilor" [Romanian's Chronicle] (in Romanian). Editura pentru literatură, București: 255–256. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Štefanovičová, Tatiana (2000). "K niektorým mýtom o počiatkch našich národných dejín" [To some myths about the beginnings of our national history] (PDF) (in Slovak). Bratislava: Univerzita Komenského.

- Štih, Peter (2010). The Middle Ages between the Eastern Alps and the Northern Adriatic: Select Papers on Slovene Historiography and Medieval History. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-18591-3.

- Szymczak, Jan (2010). "Slavic Lands: Historiography (500–1000)". In Rogers, Clifford J. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Medieval Warfare and Military Technology, Volume 3: Mercenaries-Zürich, Siege of. Oxford University Press. pp. 293–295. ISBN 978-0-19-533403-6.

- Tibenský, Ján (1958). J. Papánek — J. Sklenár. Obrancovia slovenskej národnosti v XVIII. storočí (in Slovak). Martin: Osveta.

- Tóth, Sándor László (1999). "The territories of the Hungarian Tribal Federation". In Prinzing, Günter; Salamon, Maciej (eds.). Byzanz und Ostmitteleuropa 950–1453: Beiträge zu einer table-ronde des XIX. International Congress of Byzantine Studies, Copenhagen 1996. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 22–33. ISBN 978-3-447-04146-1.

- Třeštík, Dušan (1996). "Das Großmährische Reich" – Realität oder Fiktion?: eine Neuinterpretation der Quellen zur Geschichte des mittleren Donauraumes im 9. Jahrhundert, Stuttgart, 1995 [recenze]". Český časopis historický (in Czech). Praha: Historický ústav Akademie věd ČR. 94. ISSN 0862-6111.

- Wolfram, Herwig (1995). "Historické pramene a poloha (Veľkej) Moravy" [Historical sources and the location of Great Moravia]. Historický časopis (in Slovak). Bratislava: Historický ústav Slovenskej akadémie vied. 43 (1). ISSN 0018-2575.

- Wolfram, Herwig (1997). "Moravien-Mähren oder nicht?". In Marsina, Richard; Ruttkay, Alexander (eds.). Svätopluk 894–1994 (in German). Nitra: Archeologický ústav Slovenskej akadémie vied. ISSN 0018-2575.

- Zábojník, Jozef (2004). Slovensko a avarský kaganát [Slovakia and the Avar Khaganate]] (in Slovak). Bratislava: Univerzita Komenského. ISBN 978-80-88982-83-8.