Aluminum building wiring

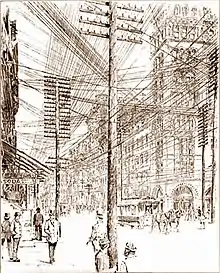

Aluminum building wiring is a type of electrical wiring for residential construction or houses that uses aluminum electrical conductors. Aluminum provides a better conductivity to weight ratio than copper, and therefore is also used for wiring power grids, including overhead power transmission lines and local power distribution lines, as well as for power wiring of some airplanes.[1][2] Utility companies have used aluminum wire for electrical transmission in power grids since around the late 1800s to the early 1900s. It has cost and weight advantages over copper wires. Aluminum wire in power transmission and distribution applications is still the preferred material today.[3]

In North American residential construction, aluminum wire was used for wiring entire houses for a short time from the 1960s to the mid-1970s during a period of high copper prices. Electrical devices (outlets, switches, lighting, fans, etc.) at the time were not designed with the particular properties of the aluminum wire being used in mind, and there were some issues related to the properties of the wire itself, making the installations with aluminum wire much more susceptible to problems. Revised manufacturing standards for both the wire and the devices were developed to reduce the problems. Existing homes with this older aluminum wiring used in branch circuits present a potential fire hazard.

Materials

Aluminum wire has been used as an electrical conductor for a considerable period of time, particularly by electrical utilities related to power transmission lines in use shortly after the beginning of modern power distribution systems being constructed starting in the late 1880s. Aluminum wire requires a larger wire gauge than copper wire to carry the same current, but is still less expensive than copper wire for a particular application.

Aluminum alloys used for electrical conductors are only approximately 61% as conductive as copper of the same cross-section, but aluminum's density is 30.5% that of copper. Accordingly, one pound of aluminum has the same current carrying capacity as two pounds of copper.[3] Since copper costs about three times as much as aluminum by weight (roughly USD $3/lb[4] vs. USD $1/lb[5] as of 2017), aluminum wires are one-sixth the cost of copper wire of the same conductivity. The lower weight of aluminum wires in particular makes these electrical conductors well suited for use in power distribution systems by electrical utilities, as supporting towers or structures only need to support half the weight of wires to carry the same current.

In the early 1960s when there was a housing construction boom in North America and the price of copper spiked, aluminum building wire was manufactured using utility grade AA-1350 aluminum alloy in sizes small enough to be used for lower load branch circuits in homes.[6] In the late 1960s problems and failures related to branch circuit connections for building wire made with the utility grade AA-1350 alloy aluminum began to surface, resulting in a re-evaluation of the use of that alloy for building wire and an identification of the need for newer alloys to produce aluminum building wire. The first 8000 series electric conductor alloy, still widely used in some applications, was developed and patented in 1972 by Aluminum Company of America (Alcoa).[7] This alloy, along with AA-8030 (patented by Olin in 1973) and AA-8176 (patented by Southwire in 1975 and 1980) perform mechanically like copper.

Unlike the older AA-1350 alloy previously used, these AA-8000 series alloys also retain their tensile strength after the standard current cycle test or the current-cycle submersion test (CCST), as described in ANSI C119.4:2004. Depending on the annealing grade, AA-8176 may elongate up to 30% with less springback effect and possesses a higher yield strength (19.8 ksi or 137 MPa, for a cold-worked AA-8076 wire).

A home with aluminum wiring installed prior to the mid-1970s (as the stock of pre-1972 aluminum wire was permitted to be used up) likely has wire made with the older AA-1350 alloy that was developed for power transmission. The AA-1350 aluminum alloy was more prone to problems related to branch circuit wiring in homes due to mechanical properties that made it more susceptible to failures resulting from the electrical devices being used at that time combined with poor workmanship.

The 1977 Beverly Hills Supper Club fire was a notable incident triggered by poorly-installed aluminum wiring.

Modern building construction

Aluminum building wiring for modern construction is manufactured with AA-8000 series aluminum alloy (sometimes referred to as "new technology" aluminum wiring) as specified by the industry standards such as the National Electrical Code (NEC). The use of larger gauge stranded aluminum wire (larger than #8 AWG) is fairly common in much of North America for modern residential construction. Aluminum wire is used in residential applications for lower voltage service feeders from the utility to the building. This is installed with materials and methods as specified by the local electrical utility companies. Also, larger aluminum stranded building wire made with AA-8000 series alloy of aluminum is used for electrical services (e.g. service entrance conductors from the utility connection to the service breaker panel) and for larger branch circuits such as for sub-panels, ranges, clothes dryers and air-conditioning units.

In the United States, solid aluminum wires made with AA-8000 series aluminum alloy are allowed for 15-A or 20-A branch circuit wiring according to the National Electrical Code.[8] The terminations need to be rated for aluminum wire, which can be problematic. This is particularly a problem with wire to wire connections made with twist-on connectors. As of 2017 most twist-on connectors for typical smaller branch circuit wire sizes, even those designed to connect copper to aluminum wiring, are not rated for aluminum-to-aluminum connections, with one exception being the Marette #63 or #65 used in Canada but not approved by UL for use in the United States. Also, the size of the aluminum wire needs to be larger compared to copper wire used for the same circuit due to the increased resistance of the aluminum alloys. For example, a 15-A branch circuit supplying standard lighting fixtures can be installed with either #14 AWG copper building wire or #12 AWG aluminum building wire according to the NEC. However, smaller solid aluminum branch circuit wiring is almost never used for residential construction in North America.[3]

Older homes

When utility grade AA-1350 alloy aluminum wire was first used in branch circuit wiring in the early 1960s, solid aluminum wire was installed the same way as copper wire with the same electrical devices.

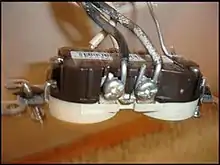

For smaller branch circuits with solid wires (15-/20-A circuits) typical connections of an electrical wire to an electrical device are usually made by wrapping the wire around a screw on the device, also called a terminal, and then tightening the screw. At around the same time the use of steel screws became more common than brass screws for electrical devices.

Over time, many of these terminations with solid aluminum wire began to fail due to improper connection techniques and the dissimilar metals having different resistances and significantly different coefficients of thermal expansion, as well as problems with properties of the solid wires. These connection failures generated heat under electrical load and caused overheated connections.

The larger size stranded aluminum wires don't have the same historical problems as solid aluminum wires, and the common terminations for larger size wires are dual-rated terminations called lugs. These lugs are typically made with a coated aluminum alloy, which can accommodate either an aluminum wire or a copper wire. Larger stranded aluminum wiring with proper terminations is generally considered safe, since long-term installations have proven its reliability.

Problems

The use of older solid aluminum wiring in residential construction has resulted in failures of connections at electrical devices, has been implicated in house fires according to the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC), and in some areas it may be difficult to obtain homeowners insurance for a house with older aluminum wiring.[9][10] There are several possible reasons why these connections failed. The two main reasons were improper installations (poor workmanship) and the differences in the coefficient of expansion between aluminum wire used in the 1960s to mid-1970s and the terminations, particularly when the termination was a steel screw on an electrical device.[11][12] The reported hazards are associated with older solid aluminum branch circuit wiring (smaller than no. 8 AWG)

Improper installations

Many terminations of aluminum wire installed in the 1960s and 1970s that were properly installed continue to operate with no problems. However, problems can develop in the future, particularly if connections were not properly installed initially.

Improper installation, or poor workmanship, includes: not abrading the wires, not applying a corrosion inhibitor, not wrapping wires around terminal screws, wrapping wires around terminal screws the wrong way, and inadequate torque on the connection screws. There can also be problems with connections made with too much torque on the connection screw as it causes damage to the wire, particularly with the softer aluminum wire.

Coefficient of expansion and creep

Most of the problems related to aluminum wire are typically associated with older (pre-1972) AA-1350 alloy solid aluminum wire, sometimes referred to as "old technology" aluminum wiring, as the properties of that wire result in significantly more expansion and contraction than copper wire or modern day AA-8000 series aluminum wire. Older solid aluminum wire also had some problems with a property called creep, which results in the wire permanently deforming or relaxing over time under load.

Aluminum wire used before the mid-1970s had a somewhat higher rate of creep, but a more significant issue was that aluminum wire critically had a coefficient of expansion that varied significantly from steel screws commonly used in lieu of brass screws around this time for terminations at devices such as outlets and switches. Aluminum and steel expand and contract at significantly different rates under thermal load, so a connection can become loose, particularly for older terminations initially installed with inadequate torque of the screws combined with creep of the aluminum over time. Loose connections get progressively worse over time.

This cycle results from the connection loosening slightly, with a reduced contact area at the connection leading to overheating, and allowing intermetallic steel/aluminum compounds to be formed between the conductor and the terminal screw. This resulted in a higher resistance junction, leading to additional overheating. Although many believe that oxidation was the issue, studies have shown that oxidation was not significant in these cases.[13]

Electrical device ratings

Many electrical devices used in the 1960s had smaller plain steel terminal screws, which made the attachment of the aluminum wires being used at that time to these devices much more vulnerable to problems. In the late 1960s, a device specification known as CU/AL (meaning copper-aluminum) was created that specified standards for devices intended for use with aluminum wire. Some of these devices used larger undercut screw terminals to more securely hold the wire.

Unfortunately, CU/AL switches and receptacles failed to work well enough with aluminum wire, and a new specification called CO/ALR (meaning copper-aluminum, revised) was created. These devices employ brass screw terminals that are designed to act as a similar metal to aluminum and to expand at a similar rate, and the screws have even deeper undercuts. The CO/ALR rating is only available for standard light switches and receptacles; CU/AL is the standard connection marking for circuit breakers and larger equipment.

Oxidation

Most metals (with a few exceptions, such as gold) oxidize freely when exposed to air. Aluminium oxide is not an electrical conductor, but rather an electrical insulator. Consequently, the flow of electrons through the oxide layer can be greatly impeded. However, since the oxide layer is only a few nanometers thick, the added resistance is not noticeable under most conditions. When aluminum wire is terminated properly, the mechanical connection breaks the thin, brittle layer of oxide to form an excellent electrical connection. Unless this connection is loosened, there is no way for oxygen to penetrate the connection point to form further oxide.

If inadequate torque is applied to the electrical device termination screw or if the devices are not CO/ALR rated (or at least CU/AL-rated for breakers and larger equipment) this can result in an inadequate connection of the aluminum wire. Also, due to the significant difference in thermal expansion rates of older aluminum wire and steel termination screws connections can loosen over time allowing the formation of some additional oxide on the wire. However, oxidation was found not to be a substantial factor in failures of aluminum wire terminations.[13]

Joining aluminum and copper wires

Another issue is the joining of aluminum wire to copper wire. In addition to the oxidation that occurs on the surface of aluminum wires which can cause a poor connection, aluminum and copper are dissimilar metals. As a result, galvanic corrosion can occur in the presence of an electrolyte, causing these connections to become unstable over time.

Upgrades and repairs

Several upgrades or repairs are available for homes with older pre-1970s aluminum branch circuit wiring:

- Completely rewiring the house with copper wires (usually cost prohibitive)

- "Pig-tailing" which involves splicing a short length of copper wire (pigtail) to the original aluminum wire, and then attaching the copper wire to the existing electrical device. The splice of the copper pigtail to the existing aluminum wire can be accomplished with special crimp connectors, special miniature lug-type connectors, or approved twist-on connectors (with special installation procedures). Pig-tailing generally saves time and money, and is possible as long as the wiring itself isn't damaged.[14]

However, the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) currently recommends only two alternatives for a "permanent repair" using the pig-tailing method. The more extensively tested method uses special crimp-on connectors called COPALUM connectors. As of April 2011, the CPSC has also recognized miniature lug-type connectors called AlumiConn connectors.[9][15] The CPSC considers the use of pigtails with wire nuts a temporary repair, and even as a temporary repair recommends special installation procedures, and notes that there can still be hazards with attempting the repairs.

COPALUM connectors use a special crimping system that creates a cold weld between the copper and aluminum wire, and is considered a permanent, maintenance-free repair. However, there may not be sufficient length of wires in enclosures to permit a special crimping tool to be used, and the resulting connections are sometimes too large to install in existing enclosures due to limited space (or "box fill"). Installing an enclosure extender for unfinished surfaces, replacing the enclosure with a larger one or installing an additional adjacent enclosure can be done to increase the available space. Also, COPALUM connectors are costly to install, require special tools that cannot simply be purchased and electricians certified to use them by the manufacturer, and it can sometimes be very difficult to find local electricians certified to install these connectors.

The AlumiConn miniature lug connector can also be used for a permanent repair.[9] The only special tool required for an electrician installing them is a special torque screwdriver that should be readily available to qualified electrical contractors. Proper torque on the connectors set screws is critical to having an acceptable repair. However, use of the Alumiconn connectors is a relatively newer repair option for older aluminum wiring compared to other methods, and use of these connectors can have some of the same or similar problems with limited enclosure space as the COPALUM connectors.

Special twist-on connectors (or "wire nuts") are available for joining aluminum to copper wire, which are pre-filled with an antioxidant compound made of zinc dust in polybutene base[16] with silicon dioxide added to the compound to abrade the wires. As of 2014 there was only one twist-on connector rated or "UL Listed" for connecting aluminum and copper branch circuit wires in the U.S., which is the Ideal no. 65 "Twister Al/Cu wire connector". These special twist-on connectors have a distinctive purple color, have been UL Listed for aluminum to copper branch circuit wire connections since 1995, and according to the manufacturer's current literature are "perfect for pig-tailing a copper conductor onto aluminum branch circuit wiring in retrofit applications".[17] The CPSC still considers the use of twist-on connectors, including the Ideal no. 65 "Twister Al/Cu wire connector", to be a temporary repair.

According to the CPSC, even using (listed) twist-on connectors to attach copper pigtails to older aluminum wires as a temporary repair requires special installation procedures, including abrading and pre-twisting the wires. However, the manufacturer's instructions for the Ideal no. 65 Twister[18] only recommends pre-twisting the wires, and does not state it is required. Also, the instructions do not mention physically abrading the wires as recommended by the CPSC, although the manufacturer current literature states the pre-filled "compound cuts aluminum oxide". Some researchers have criticized the UL listing/tests for this wire connector, and there have been reported problems with tests (without pre-twisting) and installations.[19] However, it is unknown if the reported installation problems were associated with unqualified persons attempting these repairs, or not using recommended special installation procedures (such as abrading and pre-twisting the wires as recommended by the CPSC for older aluminum wire, or at least pre-twisting the wires as recommended by Ideal for their connectors).

The use of newer CO/ALR rated devices (switches and receptacles) can be used to replace older devices that did not have the proper rating in homes with aluminum branch circuit wiring to reduce the hazards.[19] These devices are reportedly tested and listed for both AA-1350 and AA-8000 series aluminum wire, and are acceptable according to the National Electrical Code.[8] However, some manufacturers of CO/ALR devices recommend periodically checking/tightening the terminal screws on these devices which can be hazardous for unqualified individuals to attempt, and there is criticism of their use as a permanent repair as some CO/ALR devices have failed in tests when connected to "old technology" aluminum wire.[9] Furthermore, just installing CO/ALR devices (switches and receptacles) doesn't address potential hazards associated with other connections such as those at ceiling fans, lights and equipment.

See also

References

- Telecommunications and networks, Khateeb M. Hussain, Donna Hussain

- Aircraft Wire. mechanicsupport.com

- "Anaheim Aluminum Wiring Facts and Fallacies". Accurateelectricalservices.com. 2011-02-04. Archived from the original on 2013-12-07. Retrieved 2012-03-07.

Electricity is transmitted from the utility generating stations to individual meters using almost exclusively aluminum wiring. In the U.S., utilities have used aluminum wire for over 100 years.

- Copper prices and copper price charts

- Aluminum Prices and Aluminum Price Charts

- "The Evolution of Aluminum Conductors Used for Building Wire and Cable" (PDF). NEMA. 2012.

- Patent application filed in 1969

- "2017 National Electrical Code".

- "Repairing Aluminum Wiring" (PDF). CPSC Publication 516, June 2011 www.cpsc.gov.

- "What Owners Need to Know About Wiring Dangers". Washington Post Article, Real Estate, July 3, 2004.

- "Aluminum Building Wire Installation & Terminations" (PDF). Christel Hunter, IAEI News (January/February 2006).

- "Aluminum Building Wire 40 Years Later". Southwire Article.

- Newbury, Dale; Greenwald, S. (19 June 1980). "Observations on the Mechanisms of High Resistance Junction Formation in Aluminum Wire Connections" (PDF). Journal of Research of the National Bureau of Standards. 85 (6): 429–440.

- "Aluminum Wiring Pigtail Repairs". Mike Fuller Electric. Retrieved 2019-09-16.

- "CPSC Approval Letter for AlumiConn Connectors" (PDF). CPSC.

- "Ideal Noalox Antioxidant Material Safety Data Sheet" (PDF). Retrieved 2017-09-14.

- "Twister Al/Cu Wire Connector" (PDF). Ideal Twister Brochure. 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-03-06. Retrieved 2016-10-11.

- "Ideal Twister Al/Cu Plus Wire Connector Instruction Sheet" (PDF). LA-2669-3, Ideal Industries. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-05-10. Retrieved 2016-10-11.

- "Reducing the Fire Hazard in Aluminum-Wired Homes" (PDF). Report by Jesse Aronstein, PE Updated 11/25/2011.

- "Installing Aluminum Building Wire", Christel Hunter, EC&M Article, 2007.