Amitriptyline

Amitriptyline, sold under the brand name Elavil among others, is a tricyclic antidepressant primarily used to treat major depressive disorder and a variety of pain syndromes from neuropathic pain to fibromyalgia to migraine and tension headaches.[4] Due to the frequency and prominence of side effects, amitriptyline is generally considered a second-line therapy for these indications.[5][6][7][8]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌæmɪˈtrɪptɪliːn/[1] |

| Trade names | Elavil, others |

| Other names | Amitryptyline; Amytriptyline; Amitryptiline; Amitriptiline; MK-230; N-750; Ro 4-1575 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682388 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intramuscular injection |

| Drug class | Tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 30–60% |

| Protein binding | 96%[3] |

| Metabolism | Liver[3] (CYP2D6, CYP2C19) |

| Metabolites | nortriptyline |

| Elimination half-life | 10–50 hours[3] |

| Excretion | Urine[3] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.038 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C20H23N |

| Molar mass | 277.411 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 188 °C (370 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

The most common side effects are dry mouth, drowsiness, dizziness, constipation, and weight gain. Of note is sexual dysfunction, observed primarily in males. Glaucoma, liver toxicity and heart arrythmias are rare but serious side effects. Blood levels of amitriptyline vary significantly from one person to another,[9] and amitriptyline interacts with many medications potentially aggravating its side effects.

Amitriptyline was discovered in 1960[10] and approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1961.[11] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[12] It is available as a generic medication.[3] In 2017, it was the 87th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than nine million prescriptions.[13][14]

Medical uses

Amitriptyline is indicated for the treatment of major depressive disorder and neuropathic pain and for the prevention of migraine and chronic tension headache. It can be used for the treatment of nocturnal enuresis in children older than 6 after other treatments failed.[4]

Depression

Amitriptyline is rarely used as a first-line antidepressant due to its higher toxicity in overdose and generally poorer tolerability.[15] It can be tried for depression as a second-line therapy, after the failure of other treatments.[5] For treatment-resistant adolescent depression[16] or for cancer-related depression[17] amitriptyline is no better than placebo. It is sometimes used for the treatment of depression in Parkinson's disease,[18] but supporting evidence for that is lacking.[19]

Pain

Amitriptyline alleviates painful diabetic neuropathy. It is recommended by a variety of guidelines as a first or second line treatment.[6] It is as effective for this indication as gabapentine or pregabalin but less well tolerated.[20]

Low doses of amitriptyline moderately improve sleep disturbances and reduce pain and fatigue associated with fibromyalgia.[21] It is recommended for fibromyalgia accompanied by depression by Association of the Scientific Medical Societies in Germany[21] and as a second-line option for fibromyalgia, with exercise being the first line option, by European League Against Rheumatism.[7] Combinations of amitriptyline and fluoxetine or melatonin may reduce fibromyalgia pain better than either medication alone.[22]

There is some (low-quality) evidence that amitriptyline may reduce pain in cancer patients. It is recommended only as a second line therapy for non-chemotherapy-induced neuropathic or mixed neuropathic pain, if opioids did not provide the desired effect.[23]

Moderate evidence exists in favor of amitriptyline use for atypical facial pain.[24] Amitriptyline is ineffective for HIV-associated neuropathy.[20]

Headache

Amitriptyline is probably effective for the prevention of periodic migraine in adults. Amitriptyline is similar in efficacy to venlafaxine and topiramate but carries a higher burden of adverse effects than topiramate. [8] For many patients, even very small doses of amitriptyline are helpful, which may allow to minimize the side effects.[25] Amitriptyline is not significantly different from placebo when used for the prevention of migraine in children.[26]

Amitriptyline may reduce the frequency and duration of chronic tension headache, but it is associated with worse adverse effects than mirtazapine. Overall, amitriptyline is recommended for tension headache prophylaxis, along with lifestyle advice, which should include avoidance of analgesia and caffeine.[27]

Other indications

Amitriptyline is effective for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome; however, because of its side effects, it should be reserved for select patients for whom other agents do not work.[28] It is ineffective for abdominal pain in children with functional gastrointestinal disorders.[29]

Tricyclic antidepressants decrease the frequency, severity and duration of cyclic vomiting syndrome episodes. Amitriptyline, as the most commonly used of them, is recommended as a first line agent for its therapy.[30]

It may improve pain and urgency intensity associated with bladder pain syndrome and can be used in the management of this syndrome.[31][32] Amitriptyline can be used in the treatment of nocturnal enuresis in children. However, its effect is not sustained after the treatment ends. Alarm therapy gives better short- and long-term results.[33]

Contraindications and precautions

The known contraindications of amitriptyline are:[4]

- History of myocardial infarction

- History of arrhythmias, particularly any degree of heart block

- Coronary artery insufficiency

- Porphyria

- Severe liver disease

- Being under six years of age

- Patients who are taking monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) or have taken them within the last 14 days.

Amitriptyline should be used with caution in patients with epilepsy, impaired liver function, pheochromocytoma, urinary retention, prostate enlargement, hyperthyroidism, and pyloric stenosis.[4]

In patients with the rare condition of shallow anterior chamber of eyeball and narrow anterior chamber angle, amitriptyline may provoke attacks of acute glaucoma due to dilation of the pupil. It may aggravate psychosis, if used for depression with schizophrenia, or precipitate the switch to mania in those with bipolar disorder.[4]

CYP2D6 poor metabolizers should avoid amitriptyline due to increased side effects. If it is necessary to use it, half dose is recommended.[34] Amitriptyline can be used during pregnancy and lactation, in the cases when SSRI do not work.[35]

Side effects

The most frequent side effects, occurring in 20% or more of users, are dry mouth, drowsiness, dizziness, constipation, and weight gain (on average 1.8 kg[36]).[37] Other common side effects (in 10% or more) are vision problems (amblyopia, blurred vision), tachycardia, increased appetite, tremor, sexual dysfunction, fatigue/asthenia/feeling slowed down, and dyspepsia.[37]

Amitriptyline-associated sexual dysfunction seems to be mostly confined to males with depression and is expressed predominantly as erectile dysfunction and low libido disorder, with lesser frequency of ejaculatory and orgasmic problems. The rate of sexual dysfunction in males treated for indications other that depression and in females is not significantly different from placebo.[38]

Liver tests abnormalities occur in 10-12% of patients on amitriptyline, but are usually mild, asymptomatic and transient,[39] with consistently elevated alanine transaminase in 3% of all patients.[40][41] The increases of the enzymes above the 3-fold threshold of liver toxicity are uncommon, and cases of clinically apparent liver toxicity are rare;[39] nevertheless, amitriptyline is placed in the group of antidepressants with greater risks of hepatic toxicity.[40]

Amitriptyline prolongs QT interval.[42] This prolongation is relatively small at therapeutic doses[43] but becomes severe in overdose.[44]

Overdose

The symptoms and the treatment of an overdose are largely the same as for the other TCAs, including the presentation of serotonin syndrome and adverse cardiac effects. The British National Formulary notes that amitriptyline can be particularly dangerous in overdose,[45] thus it and other TCAs are no longer recommended as first-line therapy for depression. The treatment of overdose is mostly supportive as no specific antidote for amitriptyline overdose is available. Activated charcoal may reduce absorption if given within 1–2 hours of ingestion. If the affected person is unconscious or has an impaired gag reflex, a nasogastric tube may be used to deliver the activated charcoal into the stomach. ECG monitoring for cardiac conduction abnormalities is essential and if one is found close monitoring of cardiac function is advised. Body temperature should be regulated with measures such as heating blankets if necessary. Cardiac monitoring is advised for at least five days after the overdose. Benzodiazepines are recommended for control of seizures. Dialysis is of no use due to the high degree of protein binding with amitriptyline.[46]

Interactions

Oral contraceptives may increase the blood level of amitriptyline by as high as 90%.[47] The prescribing information warns that the combination of amitriptyline with monoamine oxidase inhibitors may cause potentially lethal serotonin syndrome;[4] however, this has been disputed.[48] The prescribing information cautions that some patients may experience a large increase in amitriptyline concentration in the presence of topiramate.[49] However, other literature states that there is little or no interaction: in a pharmacokinetic study topiramate only increased the level of amitriptyline by 20% and nortriptyline by 33%.[50] Amitriptiline counteracts the antihypertensive action of guanethidine.[46][51] When given with amitriptyline, other anticholinergic agents may result in hyperpyrexia or paralytic ileus.[49] Co-administration of amitriptyline and disulfiram is not recommended due to the potential for the development of toxic delirium.[46][52] Amitriptyline causes an unusual type of interaction with the anticoagulant phenprocoumon during which great fluctuations of the prothrombin time have been observed.[53]

Since amitriptyline and its active metabolite nortriptyline are primarily metabolized by cytochromes CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 (see Amitriptyline#Pharmacology), the inhibitors of these enzymes are expected to exhibit pharmacokinetic interactions with amitriptyline. According to the prescribing information, the interaction with CYP2D6 inhibitors may increase the plasma level of amitriptyline.[4] However, the results in the other literature are inconsistent:[54] the co-administration of amitriptyline with a potent CYP2D6 inhibitor paroxetine does increase the plasma levels of amitriptyline two-fold and of the main active metabolite nortriptyline 1.5-fold,[55] but combination with less potent CYP2D6 inhibitors thioridazine or levomepromazine does not affect the levels of amitriptyline and increases nortriptyline by about 1.5-fold;[56] a moderate CYP2D6 inhibitor fluoxetine does not seem to have a significant effect on the levels of amitriptyline or nortriptyline.[57][58]

A potent inhibitor of CYP2C19 and other cytochromes fluvoxamine increases the level of amitriptyline two-fold while slightly decreasing the level of nortriptyline.[57] Similar changes occur with a moderate inhibitor of CYP2C19 and other cytochromes cimetidine: amitriptyline level increases by about 70%, while nortriptyline decreases by 50%.[59] CYP3A4 inhibitor ketoconazole elevates amitriptyline level by about a quarter.[60] On the other hand, cytochrome P450 inducers such as carbamazepine and St. John's wart decrease the levels of both amitriptyline and nortriptyline[56][61]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

| Site | AMI | NTI | Species | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SERT | 2.8–36 | 15–279 | Human | [63][64] |

| NET | 19–102 | 1.8–21 | Human | [63][64] |

| DAT | 3,250 | 1,140 | Human | [63] |

| 5-HT1A | 450–1,800 | 294 | Human | [65][66] |

| 5-HT1B | 840 | ND | Rat | [67] |

| 5-HT2A | 18–23 | 41 | Human | [65][66] |

| 5-HT2B | 174 | ND | Human | [68] |

| 5-HT2C | 4-8 | 8.5 | Rat | [69] |

| 5-HT3 | 430 | 1,400 | Rat | [70] |

| 5-HT6 | 65–141 | 148 | Human/rat | [71][72][73] |

| 5-HT7 | 92.8–123 | ND | Rat | [74] |

| α1 | 4.4–24 | 55 | Human | [64][65] |

| α2 | 114–690 | 2,030 | Human | [64][65] |

| β | >10,000 | >10,000 | Rat | [75][76] |

| D1 | 89 | ND | Human | [77] |

| D2 | 196–1,460 | 2,570 | Human | [65][77] |

| D3 | 206 | ND | Human | [77] |

| D4 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| D5 | 170 | ND | Human | [77] |

| H1 | 0.5–1.1 | 3.0–15 | Human | [77][78][79] |

| H2 | 66 | 646 | Human | [78] |

| H3 | 75,900 | 45,700 | Human | [77][78] |

| H4 | 26,300 | 6,920 | Human | [78][80] |

| mACh | 9.6 | 37 | Human | [65] |

| M1 | 11.0–14.7 | 40 | Human | [81][82] |

| M2 | 11.8 | 110 | Human | [81] |

| M3 | 12.8–39 | 50 | Human | [81][82] |

| M4 | 7.2 | 84 | Human | [81] |

| M5 | 15.7–24 | 97 | Human | [81][82] |

| σ1 | 300 | 2,000 | Guinea pig | [83] |

| σ2 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| hERG | >3,000 | ND | Human | [84] |

| Values are Ki (nM), unless otherwise noted. The smaller the value, the more strongly the drug binds to the site. | ||||

Amitriptyline is classified as a tricyclic antidepressant (TCA), with strong actions on the serotonin transporter (SERT) and moderate effects on the norepinephrine transporter (NET).[63][85] It has negligible influence on the dopamine transporter (DAT) and therefore does not affect dopamine reuptake, being nearly 1,000 times weaker on inhibition of the reuptake of this neurotransmitter than on serotonin.[63] It is metabolized to nortriptyline, a more potent and selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, and this may serve to complement its effects on norepinephrine reuptake.[46]

Amitriptyline additionally acts as an antagonist or inverse agonist of the serotonin 5-HT2A, 5-HT2C, 5-HT3, 5-HT6, and 5-HT7 receptors, the α1-adrenergic receptor, the histamine H1 and H2 receptors,[86] and the muscarinic acetylcholine receptors, and as an agonist of the sigma σ1 receptor.[64][87][88][89] It has also been shown to be a relatively weak NMDA receptor antagonist via the dizocilpine (MK-801)/phencyclidine (PCP) site.[90] Amitriptyline inhibits sodium channels, L-type calcium channels, and Kv1.1, Kv7.2, and Kv7.3 voltage-gated potassium channels, and therefore acts as a sodium, calcium, and potassium channel blocker as well.[91][92]

Amitriptyline has been demonstrated to act as an agonist of the TrkA and TrkB receptors.[93] It promotes the heterodimerization of these proteins in the absence of NGF and has potent neurotrophic activity both in-vivo and in-vitro in mouse models.[93][94] These are the same receptors BDNF activates, an endogenous neurotrophin with powerful antidepressant effects, and as such this property may contribute significantly to its therapeutic efficacy against depression. Amitriptyline also acts as a functional inhibitor of acid sphingomyelinase,[95] and as a PARP1 inhibitor.[96]

Mechanism of action

Amitriptyline inhibits neuronal reuptake of serotonin and noradrenaline from the synapse in the central nervous system; this increases their availability in the synapse to cause neurotransmission on the post-synaptic neurone.[97] Amitriptyline is metabolised by cytochrome P450 enzymes in the liver to nortriptyline, which also acts as a noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor; this potentiates the antidepressant effects of amitriptyline.[98]

Pharmacokinetics

Amitriptyline is a highly lipophilic molecule having an octanol-water partition coefficient (pH 7.4) of 3.0,[99] while the log P of the free base was reported as 4.92.[100] Solubility in water is 9.71 mg/litre at 24 °C.[101]

Amitriptyline is readily absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract and is extensively metabolized on first pass through the liver.[46] It is metabolized mostly by CYP2D6, CYP3A4, and CYP2C19-mediated N-demethylation into nortriptyline,[46] which is another TCA in its own right.[102] It is 96% bound to plasma proteins; nortriptyline is 93–95% bound to plasma proteins.[46][103] It is mostly excreted in the urine (around 30–50%) as metabolites either free or as glucuronide and sulfate conjugates within 24 hours.[46] 2% of the unchanged drug is excreted in the urine.[97] Small amounts are also excreted in feces.[104] Amitriptyline has an elimination half life of 25 hours and its volume of distribution is 10–50L/kg.[98]

Therapeutic levels of amitriptyline range from 75 to 175 ng/mL (270–631 nM),[105] or 80–250 ng/mL of both amitriptyline and its metabolite nortriptyline.[106]

Pharmacogenetics

Since amitriptyline is primarily metabolized by CYP2D6 and CYP2C19, genetic variations within the genes coding for these enzymes can affect its metabolism, leading to changes in the concentrations of the drug in the body.[107] Increased concentrations of amitriptyline may increase the risk for side effects, including anticholinergic and nervous system adverse effects, while decreased concentrations may reduce the drug's efficacy.[108][109][110][111]

Individuals can be categorized into different types of CYP2D6 or CYP2C19 metabolizers depending on which genetic variations they carry. These metabolizer types include poor, intermediate, extensive, and ultrarapid metabolizers. Most individuals (about 77–92%) are extensive metabolizers,[34] and have "normal" metabolism of amitriptyline. Poor and intermediate metabolizers have reduced metabolism of the drug as compared to extensive metabolizers; patients with these metabolizer types may have an increased probability of experiencing side effects. Ultrarapid metabolizers use amitriptyline much faster than extensive metabolizers; patients with this metabolizer type may have a greater chance of experiencing pharmacological failure.[108][109][34][111]

The Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium recommends avoiding amitriptyline in patients who are CYP2D6 ultrarapid or poor metabolizers, due to the risk for a lack of efficacy and side effects, respectively. The consortium also recommends considering an alternative drug not metabolized by CYP2C19 in patients who are CYP2C19 ultrarapid metabolizers. A reduction in starting dose is recommended for patients who are CYP2D6 intermediate metabolizers and CYP2C19 poor metabolizers. If use of amitriptyline is warranted, therapeutic drug monitoring is recommended to guide dose adjustments.[34] The Dutch Pharmacogenetics Working Group also recommends selecting an alternative drug or monitoring plasma concentrations of amitriptyline in patients who are CYP2D6 poor or ultrarapid metabolizers, and selecting an alternative drug or reducing initial dose in patients who are CYP2D6 intermediate metabolizers.[112]

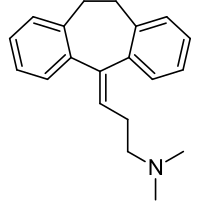

Chemistry

Amitriptyline is a tricyclic compound, specifically a dibenzocycloheptadiene, and possesses three rings fused together with a side chain attached in its chemical structure.[113] Other dibenzocycloheptadiene TCAs include nortriptyline (noramitriptyline, N-desmethylamitriptyline), protriptyline, and butriptyline.[113] Amitriptyline is a tertiary amine TCA, with its side chain-demethylated metabolite nortriptyline being a secondary amine.[114][115] Other tertiary amine TCAs include imipramine, clomipramine, dosulepin (dothiepin), doxepin, and trimipramine.[116][117] The chemical name of amitriptyline is 3-(10,11-dihydro-5H-dibenzo[a,d]cycloheptene-5-ylidene)-N,N-dimethylpropan-1-amine and its free base form has a chemical formula of C20H23N with a molecular weight of 277.403 g/mol.[118] The drug is used commercially mostly as the hydrochloride salt; the free base form is used rarely and the embonate (pamoate) salt is used for intramuscular administration.[118][119] The CAS Registry Number of the free base is 50-48-6, of the hydrochloride is 549-18-8, and of the embonate is 17086-03-2.[118][119]

History

Amitriptyline was first synthesized in 1960 and was introduced for medical use in United States in 1961 and in the United Kingdom in 1962, in both countries under the brand name Elavil.[120][121][122][123] It was the second TCA to be introduced, following the introduction of imipramine in 1957.[121][122]

Society and culture

English folk singer Nick Drake died from an overdose of Tryptizol in 1974.[124]

Generic names

Amitriptyline is the English and French generic name of the drug and its INN, BAN, and DCF, while amitriptyline hydrochloride is its USAN, USP, BANM, and JAN.[118][119][125][126] Its generic name in Spanish and Italian and its DCIT are amitriptilina, in German is Amitriptylin, and in Latin is amitriptylinum.[119][126] The embonate salt is known as amitriptyline embonate, which is its BANM, or as amitriptyline pamoate unofficially.[119]

Brand names

As of September 2018, amitriptyline was marketed under many brand names worldwide alone and as a combination drug with each of chlordiazepoxide, perphenazine, and medazepam.[127]

Brands include Adepril, ADT, Ambival, Amicon, Amilavil, Amilin, Amiline, Amineurin, Amiplin, Amirol, Amit, Amitin, Amitone, Amitrac, Amitrip, Amitriptilina, Amitriptilino, Amitriptilins, Amitriptine, Amitriptylin, Amitriptyline, Amitriptylinhydrochlorid, Amitriptylini, Amitriptylinum, Amitryp, Amotrip, Amyline, Amypres, Amytril, Amyzol, Anapsique, Arpidox, Deprelio, Elatrol, Elatrolet, Elavil, Endep, Fiorda, Laroxyl, Latilin, Levate, Maxitrip, Maxivalet, Mitryp, Modup, Normaln, Odep, Pinsaun, Polytanol, Protanol, Qualitriptine, Redomex, Saroten, Sarotex, Stelminal, Syneudon, Teperin, Trepiline, Triamyl, Trilin, Trip, Tripta, Triptiline, Triptizol, Triptric, Triptyl, Triptyline, Tripyline, Trynol, Tryptalgin, Tryptanol, Tryptin, Tryptizol, Tryptomer, and Vanatrip.[127]

Brands as of that date for the combination with chlordiazepoxide included Amicon Forte, Amitrac-CZ, Amypres-C, Antalin, Antalin Forte, Arpidox-CP, Axeptyl, Diapatol, Diaztric-A, Emotrip, Klotriptyl, Libotryp, Limbatril, Limbitrol, Limbitryl, Limbival, Limbritol, Maxitrip-CZ, Mitryp Forte, Morelin, Ristryl, and Sedans.[127]

Brands as of that date for the combination with perphenazine included Levazine, Minitran, Mutabase, Mutabon, Pertriptyl, Triavil, and Triptafen.[127]

Brands as of that date for the combination with medazepam included Nobritol.[127]

Research

Amitriptyline has been studied in several disorders:

- Eating disorders:[104] The few randomized controlled trials investigating its efficacy in eating disorders have been discouraging.[128]

- Insomnia: As of 2004, amitriptyline was the most commonly prescribed off-label prescription sleep aid in the United States.[129] Owing to the development of tolerance and the potential for adverse effects such as constipation, its use in the elderly for this indication is recommended against.[15]

- Urinary incontinence. An accepted use for amitriptyline in Australia and Brazil is the treatment of urinary urge incontinence.[15][130]

- Cyclic vomiting syndrome[131][132]

- Preventive treatment for patients with recurring biliary dyskinesia (sphincter of Oddi dysfunction)[133]

- Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (in addition to, or sometimes in place of ADHD stimulant drugs)[134]

- Retching/dry heaving, especially after the anti-reflux procedure Nissen fundoplication[135]

References

- "Amitriptyline | Definition of Amitriptyline by Oxford Dictionary on Lexico.com also meaning of Amitriptyline". Lexico Dictionaries | English. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- "Amitriptyline Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 2 September 2020. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- "Amitriptyline Hydrochloride". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 24 September 2014. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- "Amitriptyline Tablets BP 50mg – Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC)". electronic Medicines Compendium. Actavis UK Ltd. 24 March 2013. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- Hitchings A, Lonsdale D, Burrage D, Baker E (2015). Top 100 drugs : clinical pharmacology and practical prescribing. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-7020-5516-4.

- Alam U, Sloan G, Tesfaye S (March 2020). "Treating Pain in Diabetic Neuropathy: Current and Developmental Drugs". Drugs. 80 (4): 363–384. doi:10.1007/s40265-020-01259-2. PMID 32040849.

- Macfarlane GJ, Kronisch C, Dean LE, Atzeni F, Häuser W, Fluß E, Choy E, Kosek E, Amris K, Branco J, Dincer F, Leino-Arjas P, Longley K, McCarthy GM, Makri S, Perrot S, Sarzi-Puttini P, Taylor A, Jones GT (February 2017). "EULAR revised recommendations for the management of fibromyalgia". Ann Rheum Dis. 76 (2): 318–328. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209724. PMID 27377815.

- Silberstein SD, Holland S, Freitag F, Dodick DW, Argoff C, Ashman E (April 2012). "Evidence-based guideline update: pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society". Neurology. 78 (17): 1337–45. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182535d20. PMC 3335452. PMID 22529202.

- Tfelt-Hansen P, Ågesen FN, Pavbro A, Tfelt-Hansen J (May 2017). "Pharmacokinetic Variability of Drugs Used for Prophylactic Treatment of Migraine". CNS Drugs. 31 (5): 389–403. doi:10.1007/s40263-017-0430-3. PMID 28405886.

- Sneader W (2005). Drug Discovery a History. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. p. 414. ISBN 9780470015520. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- Fangmann P, Assion HJ, Juckel G, González CA, López-Muñoz F (February 2008). "Half a century of antidepressant drugs: on the clinical introduction of monoamine oxidase inhibitors, tricyclics, and tetracyclics. Part II: tricyclics and tetracyclics". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 28 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1097/jcp.0b013e3181627b60. PMID 18204333. S2CID 31018835.

- World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- "Amitriptyline - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- Rossi, S, ed. (2013). Australian Medicines Handbook (2013 ed.). Adelaide: The Australian Medicines Handbook Unit Trust. ISBN 978-0-9805790-9-3.

- Zhou X, Michael KD, Liu Y, Del Giovane C, Qin B, Cohen D, Gentile S, Xie P (November 2014). "Systematic review of management for treatment-resistant depression in adolescents". BMC Psychiatry. 14: 340. doi:10.1186/s12888-014-0340-6. PMC 4254264. PMID 25433401.

- Riblet N, Larson R, Watts BV, Holtzheimer P (2014). "Reevaluating the role of antidepressants in cancer-related depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 36 (5): 466–73. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.05.010. PMID 24950919.

- Parkinson's disease Archived 18 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. August 2007. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

- Seppi K, Weintraub D, Coelho M, Perez-Lloret S, Fox SH, Katzenschlager R, Hametner EM, Poewe W, Rascol O, Goetz CG, Sampaio C (October 2011). "The Movement Disorder Society Evidence-Based Medicine Review Update: Treatments for the non-motor symptoms of Parkinson's disease". Mov Disord. 26 Suppl 3: S42–80. doi:10.1002/mds.23884. PMC 4020145. PMID 22021174.

- Liampas A, Rekatsina M, Vadalouca A, Paladini A, Varrassi G, Zis P (November 2020). "Pharmacological Management of Painful Peripheral Neuropathies: A Systematic Review". Pain Ther. doi:10.1007/s40122-020-00210-3. PMID 33145709.

- Sommer C, Alten R, Bär KJ, Bernateck M, Brückle W, Friedel E, Henningsen P, Petzke F, Tölle T, Üçeyler N, Winkelmann A, Häuser W (June 2017). "[Drug therapy of fibromyalgia syndrome : Updated guidelines 2017 and overview of systematic review articles]". Schmerz (in German). 31 (3): 274–284. doi:10.1007/s00482-017-0207-0. PMID 28493231.

- Thorpe J, Shum B, Moore RA, Wiffen PJ, Gilron I (February 2018). "Combination pharmacotherapy for the treatment of fibromyalgia in adults". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2: CD010585. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010585.pub2. PMC 6491103. PMID 29457627.

- van den Beuken-van Everdingen MH, de Graeff A, Jongen JL, Dijkstra D, Mostovaya I, Vissers KC (March 2017). "Pharmacological Treatment of Pain in Cancer Patients: The Role of Adjuvant Analgesics, a Systematic Review". Pain Pract. 17 (3): 409–419. doi:10.1111/papr.12459. PMID 27207115.

- Do TM, Unis GD, Kattar N, Ananth A, McCoul ED (October 2020). "Neuromodulators for Atypical Facial Pain and Neuralgias: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Laryngoscope. doi:10.1002/lary.29162. PMID 33037835.

- Loder E, Rizzoli P (November 2018). "Pharmacologic Prevention of Migraine: A Narrative Review of the State of the Art in 2018". Headache. 58 Suppl 3: 218–229. doi:10.1111/head.13375. PMID 30137671.

- Oskoui M, Pringsheim T, Billinghurst L, Potrebic S, Gersz EM, Gloss D, Holler-Managan Y, Leininger E, Licking N, Mack K, Powers SW, Sowell M, Victorio MC, Yonker M, Zanitsch H, Hershey AD (September 2019). "Practice guideline update summary: Pharmacologic treatment for pediatric migraine prevention: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society". Neurology. 93 (11): 500–509. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000008105. PMC 6746206. PMID 31413170.

- Ghadiri-Sani M, Silver N (February 2016). "Headache (chronic tension-type)". BMJ Clin Evid. 2016. PMC 4747324. PMID 26859719.

- Trinkley KE, Nahata MC (2014). "Medication management of irritable bowel syndrome". Digestion. 89 (4): 253–67. doi:10.1159/000362405. PMID 24992947.

- Kaminski A, Kamper A, Thaler K, Chapman A, Gartlehner G (July 2011). "Antidepressants for the treatment of abdominal pain-related functional gastrointestinal disorders in children and adolescents". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (7): CD008013. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008013.pub2. PMC 6769179. PMID 21735420.

- Venkatesan T, Levinthal DJ, Tarbell SE, Jaradeh SS, Hasler WL, Issenman RM, Adams KA, Sarosiek I, Stave CD, Sharaf RN, Sultan S, Li BU (June 2019). "Guidelines on management of cyclic vomiting syndrome in adults by the American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society and the Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome Association". Neurogastroenterol Motil. 31 Suppl 2: e13604. doi:10.1111/nmo.13604. PMC 6899751. PMID 31241819.

- Giusto LL, Zahner PM, Shoskes DA (July 2018). "An evaluation of the pharmacotherapy for interstitial cystitis". Expert Opin Pharmacother. 19 (10): 1097–1108. doi:10.1080/14656566.2018.1491968. PMID 29972328.

- Colemeadow J, Sahai A, Malde S (2020). "Clinical Management of Bladder Pain Syndrome/Interstitial Cystitis: A Review on Current Recommendations and Emerging Treatment Options". Res Rep Urol. 12: 331–343. doi:10.2147/RRU.S238746. PMC 7455607. PMID 32904438.

- Caldwell PH, Sureshkumar P, Wong WC (January 2016). "Tricyclic and related drugs for nocturnal enuresis in children". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD002117. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002117.pub2. PMID 26789925.

- Hicks JK, Swen JJ, Thorn CF, Sangkuhl K, Kharasch ED, Ellingrod VL, Skaar TC, Müller DJ, Gaedigk A, Stingl JC (May 2013). "Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium guideline for CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 genotypes and dosing of tricyclic antidepressants". Clin Pharmacol Ther. 93 (5): 402–8. doi:10.1038/clpt.2013.2. PMC 3689226. PMID 23486447.

- Nielsen RE, Damkier P (June 2012). "Pharmacological treatment of unipolar depression during pregnancy and breast-feeding--a clinical overview". Nord J Psychiatry. 66 (3): 159–66. doi:10.3109/08039488.2011.650198. PMID 22283766.

- Domecq JP, Prutsky G, Leppin A, Sonbol MB, Altayar O, Undavalli C, Wang Z, Elraiyah T, Brito JP, Mauck KF, Lababidi MH, Prokop LJ, Asi N, Wei J, Fidahussein S, Montori VM, Murad MH (February 2015). "Clinical review: Drugs commonly associated with weight change: a systematic review and meta-analysis". J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 100 (2): 363–70. doi:10.1210/jc.2014-3421. PMC 5393509. PMID 25590213.

- Leucht C, Huhn M, Leucht S (December 2012). "Amitriptyline versus placebo for major depressive disorder". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 12: CD009138. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009138.pub2. PMID 23235671.

- Chen LW, Chen MY, Lian ZP, Lin HS, Chien CC, Yin HL, Chu YH, Chen KY (March 2018). "Amitriptyline and Sexual Function: A Systematic Review Updated for Sexual Health Practice". Am J Mens Health. 12 (2): 370–379. doi:10.1177/1557988317734519. PMC 5818113. PMID 29019272.

- Amitriptyline. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. 6 January 2012. PMID 31643729. Retrieved 6 January 2021 – via PubMed.

- Voican CS, Corruble E, Naveau S, Perlemuter G (April 2014). "Antidepressant-induced liver injury: a review for clinicians". Am J Psychiatry. 171 (4): 404–15. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13050709. PMID 24362450.

- HOLMBERG MB, JANSSON (1962). "A study of blood count and serum transaminase in prolonged treatment with amitriptyline". J New Drugs. 2: 361–5. doi:10.1177/009127006200200606. PMID 13961401.

- Zemrak WR, Kenna GA (June 2008). "Association of antipsychotic and antidepressant drugs with Q-T interval prolongation". American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 65 (11): 1029–38. doi:10.2146/ajhp070279. PMID 18499875. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016.

- Hefner G, Hahn M, Hohner M, Roll SC, Klimke A, Hiemke C (January 2019). "QTc Time Correlates with Amitriptyline and Venlafaxine Serum Levels in Elderly Psychiatric Inpatients". Pharmacopsychiatry. 52 (1): 38–43. doi:10.1055/s-0044-102009. PMID 29466824.

- Campleman SL, Brent J, Pizon AF, Shulman J, Wax P, Manini AF (December 2020). "Drug-specific risk of severe QT prolongation following acute drug overdose". Clin Toxicol (Phila). 58 (12): 1326–1334. doi:10.1080/15563650.2020.1746330. PMID 32252558.

- Joint Formulary Committee (2013). British National Formulary (BNF) (65th ed.). London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. ISBN 978-0-85711-084-8.

- "Endep Amitriptyline hydrochloride" (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. Alphapharm Pty Limited. 10 December 2012. Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- Berry-Bibee EN, Kim MJ, Simmons KB, Tepper NK, Riley HE, Pagano HP, Curtis KM (December 2016). "Drug interactions between hormonal contraceptives and psychotropic drugs: a systematic review". Contraception. 94 (6): 650–667. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2016.07.011. PMID 27444984.

- Gillman PK (June 2006). "A review of serotonin toxicity data: implications for the mechanisms of antidepressant drug action". Biol Psychiatry. 59 (11): 1046–51. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.11.016. PMID 16460699.

- "DailyMed - AMITRIPTYLINE HYDROCHLORIDE tablet, film coated".

- Bialer M, Doose DR, Murthy B, Curtin C, Wang SS, Twyman RE, Schwabe S (2004). "Pharmacokinetic interactions of topiramate". Clin Pharmacokinet. 43 (12): 763–80. doi:10.2165/00003088-200443120-00001. PMID 15355124.

- Meyer JF, McAllister CK, Goldberg LI (August 1970). "Insidious and prolonged antagonism of guanethidine by amitriptyline". JAMA. 213 (9): 1487–8. PMID 5468457.

- Maany I, Hayashida M, Pfeffer SL, Kron RE (June 1982). "Possible toxic interaction between disulfiram and amitriptyline". Arch Gen Psychiatry. 39 (6): 743–4. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290060083018. PMID 7092508.

- "CHAPTER 132 ORAL ANTICOAGULATION | Free Medical Textbook".

- Breyer-Pfaff U (October 2004). "The metabolic fate of amitriptyline, nortriptyline and amitriptylinoxide in man". Drug Metab Rev. 36 (3–4): 723–46. doi:10.1081/dmr-200033482. PMID 15554244.

- Leucht S, Hackl HJ, Steimer W, Angersbach D, Zimmer R (January 2000). "Effect of adjunctive paroxetine on serum levels and side-effects of tricyclic antidepressants in depressive inpatients". Psychopharmacology (Berl). 147 (4): 378–83. doi:10.1007/s002130050006. PMID 10672631.

- Jerling M, Bertilsson L, Sjöqvist F (February 1994). "The use of therapeutic drug monitoring data to document kinetic drug interactions: an example with amitriptyline and nortriptyline". Ther Drug Monit. 16 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1097/00007691-199402000-00001. PMID 7909176.

- Vandel S, Bertschy G, Baumann P, Bouquet S, Bonin B, Francois T, Sechter D, Bizouard P (June 1995). "Fluvoxamine and fluoxetine: interaction studies with amitriptyline, clomipramine and neuroleptics in phenotyped patients". Pharmacol Res. 31 (6): 347–53. doi:10.1016/1043-6618(95)80088-3. PMID 8685072.

- Vandel S, Bertschy G, Bonin B, Nezelof S, François TH, Vandel B, Sechter D, Bizouard P (1992). "Tricyclic antidepressant plasma levels after fluoxetine addition". Neuropsychobiology. 25 (4): 202–7. doi:10.1159/000118838. PMID 1454161.

- Curry SH, DeVane CL, Wolfe MM (1985). "Cimetidine interaction with amitriptyline". Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 29 (4): 429–33. doi:10.1007/BF00613457. PMID 3912187.

- Venkatakrishnan K, Schmider J, Harmatz JS, Ehrenberg BL, von Moltke LL, Graf JA, Mertzanis P, Corbett KE, Rodriguez MC, Shader RI, Greenblatt DJ (October 2001). "Relative contribution of CYP3A to amitriptyline clearance in humans: in vitro and in vivo studies". J Clin Pharmacol. 41 (10): 1043–54. doi:10.1177/00912700122012634. PMID 11583471.

- Johne A, Schmider J, Brockmöller J, Stadelmann AM, Störmer E, Bauer S, Scholler G, Langheinrich M, Roots I (February 2002). "Decreased plasma levels of amitriptyline and its metabolites on comedication with an extract from St. John's wort ( Hypericum perforatum )". J Clin Psychopharmacol. 22 (1): 46–54. doi:10.1097/00004714-200202000-00008. PMID 11799342.

- Roth BL, Driscol J. "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- Tatsumi M, Groshan K, Blakely RD, Richelson E (1997). "Pharmacological profile of antidepressants and related compounds at human monoamine transporters". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 340 (2–3): 249–58. doi:10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01393-9. PMID 9537821.

- Owens MJ, Morgan WN, Plott SJ, Nemeroff CB (1997). "Neurotransmitter receptor and transporter binding profile of antidepressants and their metabolites". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 283 (3): 1305–22. PMID 9400006.

- Cusack B, Nelson A, Richelson E (1994). "Binding of antidepressants to human brain receptors: focus on newer generation compounds". Psychopharmacology. 114 (4): 559–65. doi:10.1007/bf02244985. PMID 7855217. S2CID 21236268.

- Peroutka SJ (1988). "Antimigraine drug interactions with serotonin receptor subtypes in human brain". Ann. Neurol. 23 (5): 500–4. doi:10.1002/ana.410230512. PMID 2898916. S2CID 41570165.

- Peroutka SJ (1986). "Pharmacological differentiation and characterization of 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, and 5-HT1C binding sites in rat frontal cortex". J. Neurochem. 47 (2): 529–40. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.1986.tb04532.x. PMID 2942638. S2CID 25108290.

- Schmuck K, Ullmer C, Kalkman HO, Probst A, Lubbert H (1996). "Activation of meningeal 5-HT2B receptors: an early step in the generation of migraine headache?". Eur. J. Neurosci. 8 (5): 959–67. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9568.1996.tb01583.x. PMID 8743744. S2CID 19578349.

- Pälvimäki EP, Roth BL, Majasuo H, Laakso A, Kuoppamäki M, Syvälahti E, Hietala J (1996). "Interactions of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors with the serotonin 5-HT2c receptor". Psychopharmacology. 126 (3): 234–40. doi:10.1007/bf02246453. PMID 8876023. S2CID 24889381.

- Schmidt AW, Hurt SD, Peroutka SJ (1989). "'[3H]quipazine' degradation products label 5-HT uptake sites". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 171 (1): 141–3. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(89)90439-1. PMID 2533080.

- Kohen R, Metcalf MA, Khan N, Druck T, Huebner K, Lachowicz JE, Meltzer HY, Sibley DR, Roth BL, Hamblin MW (1996). "Cloning, characterization, and chromosomal localization of a human 5-HT6 serotonin receptor". J. Neurochem. 66 (1): 47–56. doi:10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.66010047.x. PMID 8522988. S2CID 35874409.

- Hirst WD, Abrahamsen B, Blaney FE, Calver AR, Aloj L, Price GW, Medhurst AD (2003). "Differences in the central nervous system distribution and pharmacology of the mouse 5-hydroxytryptamine-6 receptor compared with rat and human receptors investigated by radioligand binding, site-directed mutagenesis, and molecular modeling". Mol. Pharmacol. 64 (6): 1295–308. doi:10.1124/mol.64.6.1295. PMID 14645659. S2CID 33743899.

- Monsma FJ, Shen Y, Ward RP, Hamblin MW, Sibley DR (1993). "Cloning and expression of a novel serotonin receptor with high affinity for tricyclic psychotropic drugs". Mol. Pharmacol. 43 (3): 320–7. PMID 7680751.

- Shen Y, Monsma FJ, Metcalf MA, Jose PA, Hamblin MW, Sibley DR (1993). "Molecular cloning and expression of a 5-hydroxytryptamine7 serotonin receptor subtype". J. Biol. Chem. 268 (24): 18200–4. PMID 8394362.

- Bylund DB, Snyder SH (1976). "Beta adrenergic receptor binding in membrane preparations from mammalian brain". Mol. Pharmacol. 12 (4): 568–80. PMID 8699.

- Sánchez C, Hyttel J (1999). "Comparison of the effects of antidepressants and their metabolites on reuptake of biogenic amines and on receptor binding". Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 19 (4): 467–89. doi:10.1023/A:1006986824213. PMID 10379421. S2CID 19490821.

- von Coburg Y, Kottke T, Weizel L, Ligneau X, Stark H (2009). "Potential utility of histamine H3 receptor antagonist pharmacophore in antipsychotics". Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 19 (2): 538–42. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.09.012. PMID 19091563.

- Appl H, Holzammer T, Dove S, Haen E, Strasser A, Seifert R (February 2012). "Interactions of recombinant human histamine H1, H2, H3, and H4 receptors with 34 antidepressants and antipsychotics". Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 385 (2): 145–70. doi:10.1007/s00210-011-0704-0. PMID 22033803. S2CID 14274150.

- Ghoneim OM, Legere JA, Golbraikh A, Tropsha A, Booth RG (2006). "Novel ligands for the human histamine H1 receptor: synthesis, pharmacology, and comparative molecular field analysis studies of 2-dimethylamino-5-(6)-phenyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalenes". Bioorg. Med. Chem. 14 (19): 6640–58. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2006.05.077. PMID 16782354.

- Nguyen T, Shapiro DA, George SR, Setola V, Lee DK, Cheng R, Rauser L, Lee SP, Lynch KR, Roth BL, O'Dowd BF (2001). "Discovery of a novel member of the histamine receptor family". Mol. Pharmacol. 59 (3): 427–33. doi:10.1124/mol.59.3.427. PMID 11179435.

- Stanton T, Bolden-Watson C, Cusack B, Richelson E (1993). "Antagonism of the five cloned human muscarinic cholinergic receptors expressed in CHO-K1 cells by antidepressants and antihistaminics". Biochem. Pharmacol. 45 (11): 2352–4. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(93)90211-e. PMID 8100134.

- Bymaster FP, Nelson DL, DeLapp NW, Falcone JF, Eckols K, Truex LL, Foreman MM, Lucaites VL, Calligaro DO (1999). "Antagonism by olanzapine of dopamine D1, serotonin2, muscarinic, histamine H1 and alpha 1-adrenergic receptors in vitro". Schizophr. Res. 37 (1): 107–22. doi:10.1016/s0920-9964(98)00146-7. PMID 10227113. S2CID 19891653.

- Weber E, Sonders M, Quarum M, McLean S, Pou S, Keana JF (1986). "1,3-Di(2-[5-3H]tolyl)guanidine: a selective ligand that labels sigma-type receptors for psychotomimetic opiates and antipsychotic drugs". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 83 (22): 8784–8. Bibcode:1986PNAS...83.8784W. doi:10.1073/pnas.83.22.8784. PMC 387016. PMID 2877462.

- Teschemacher AG, Seward EP, Hancox JC, Witchel HJ (1999). "Inhibition of the current of heterologously expressed HERG potassium channels by imipramine and amitriptyline". Br. J. Pharmacol. 128 (2): 479–85. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0702800. PMC 1571643. PMID 10510461.

- "Potency of antidepressants to block noradrenaline reuptake". CNS Forum. Archived from the original on 8 November 2012. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- Ellis A, Ellis GP (1 January 1987). Progress in Medicinal Chemistry. Elsevier. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-444-80876-9. Archived from the original on 13 June 2013. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- Schatzberg AF, Nemeroff CB (2006). Essentials of clinical psychopharmacology. American Psychiatric Pub. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-58562-243-6.

- Rauser L, Savage JE, Meltzer HY, Roth BL (October 2001). "Inverse agonist actions of typical and atypical antipsychotic drugs at the human 5-hydroxytryptamine(2C) receptor". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 299 (1): 83–9. PMID 11561066.

- Werling LL, Keller A, Frank JG, Nuwayhid SJ (October 2007). "A comparison of the binding profiles of dextromethorphan, memantine, fluoxetine and amitriptyline: treatment of involuntary emotional expression disorder". Exp. Neurol. 207 (2): 248–57. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.06.013. PMID 17689532. S2CID 38476281.

- Sills MA, Loo PS (July 1989). "Tricyclic antidepressants and dextromethorphan bind with higher affinity to the phencyclidine receptor in the absence of magnesium and L-glutamate". Mol. Pharmacol. 36 (1): 160–5. PMID 2568580.

- Pancrazio JJ, Kamatchi GL, Roscoe AK, Lynch C (January 1998). "Inhibition of neuronal Na+ channels by antidepressant drugs". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 284 (1): 208–14. PMID 9435180.

- Punke MA, Friederich P (May 2007). "Amitriptyline is a potent blocker of human Kv1.1 and Kv7.2/7.3 channels". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 104 (5): 1256–1264. doi:10.1213/01.ane.0000260310.63117.a2. PMID 17456683. S2CID 21924741.

- Jang SW, Liu X, Chan CB, Weinshenker D, Hall RA, Xiao G, Ye K (June 2009). "Amitriptyline is a TrkA and TrkB receptor agonist that promotes TrkA/TrkB heterodimerization and has potent neurotrophic activity". Chemistry & Biology. 16 (6): 644–56. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.05.010. PMC 2844702. PMID 19549602.

- "Pharmaceutical Information – AMITRIPTYLINE". RxMed. Archived from the original on 27 December 2012. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- Kornhuber J, Muehlbacher M, Trapp S, Pechmann S, Friedl A, Reichel M, et al. (2011). Riezman H (ed.). "Identification of novel functional inhibitors of acid sphingomyelinase". PLOS ONE. 6 (8): e23852. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...623852K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0023852. PMC 3166082. PMID 21909365.

- Fu L, Wang S, Wang X, Wang P, Zheng Y, Yao D, et al. (December 2016). "Crystal structure-based discovery of a novel synthesized PARP1 inhibitor (OL-1) with apoptosis-inducing mechanisms in triple-negative breast cancer". Scientific Reports. 6 (1): 3. doi:10.1038/s41598-016-0007-2. PMC 5431371. PMID 28442756.

- "Amitriptyline". drugbank.ca. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- Gillman PK (July 2007). "Tricyclic antidepressant pharmacology and therapeutic drug interactions updated". British Journal of Pharmacology. 151 (6): 737–48. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0707253. PMC 2014120. PMID 17471183.

- The Pharmaceutical Codex. 1994. Principles and practice of pharmaceutics, 12th edn. Pharmaceutical press

- Hansch C, Leo A, Hoekman D. 1995. Exploring QSAR.Hydrophobic, electronic and steric constants. Washington, DC: American Chemical Society.

- Yalkowsky SH, Dannenfelser RM; The AQUASOL dATAbASE of Aqueous Solubility. Ver 5. Tucson, AZ: Univ AZ, College of Pharmacy (1992)

- Amitriptyline. Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference. London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. 30 January 2013. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

- "Pamelor, Aventyl (nortriptyline) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

- "Levate (amitriptyline), dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- Sadock BJ, Sadock VA (2008). Kaplan & Sadock's Concise Textbook of Clinical Psychiatry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 18–. ISBN 978-0-7817-8746-8. Archived from the original on 8 July 2017.

- Orsulak PJ (September 1989). "Therapeutic monitoring of antidepressant drugs: guidelines updated". Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. 11 (5): 497–507. doi:10.1097/00007691-198909000-00002. PMID 2683251.

- Rudorfer MV, Potter WZ (1999). "Metabolism of tricyclic antidepressants". Cell Mol Neurobiol. 19 (3): 373–409. doi:10.1023/A:1006949816036. PMID 10319193. S2CID 7940406.

- Stingl JC, Brockmoller J, Viviani R (2013). "Genetic variability of drug-metabolizing enzymes: the dual impact on psychiatric therapy and regulation of brain function". Mol Psychiatry. 18 (3): 273–87. doi:10.1038/mp.2012.42. PMID 22565785. S2CID 20888081.

- Kirchheiner J, Seeringer A (2007). "Clinical implications of pharmacogenetics of cytochrome P450 drug metabolizing enzymes". Biochim Biophys Acta. 1770 (3): 489–94. doi:10.1016/j.bbagen.2006.09.019. PMID 17113714.

- Hicks JK, Swen JJ, Thorn CF, Sangkuhl K, Kharasch ED, Ellingrod VL, Skaar TC, Muller DJ, Gaedigk A, Stingl JC (2013). "Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium Guideline for CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 Genotypes and Dosing of Tricyclic Antidepressants" (PDF). Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 93 (5): 402–8. doi:10.1038/clpt.2013.2. PMC 3689226. PMID 23486447.

- Dean L (2017). "Amitriptyline Therapy and CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 Genotype". In Pratt VM, McLeod HL, Rubinstein WS, et al. (eds.). Medical Genetics Summaries. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). PMID 28520380. Bookshelf ID: NBK425165.

- Swen JJ, Nijenhuis M, de Boer A, Grandia L, Maitland-van der Zee AH, Mulder H, Rongen GA, van Schaik RH, Schalekamp T, Touw DJ, van der Weide J, Wilffert B, Deneer VH, Guchelaar HJ (2011). "Pharmacogenetics: from bench to byte—an update of guidelines". Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 89 (5): 662–73. doi:10.1038/clpt.2011.34. PMID 21412232. S2CID 2475005.

- Ritsner MS (15 February 2013). Polypharmacy in Psychiatry Practice, Volume I: Multiple Medication Use Strategies. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 270–271. ISBN 978-94-007-5805-6. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- Cutler NR, Sramek JJ, Narang PK (20 September 1994). Pharmacodynamics and Drug Development: Perspectives in Clinical Pharmacology. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 160–. ISBN 978-0-471-95052-3.

- Anzenbacher P, Zanger UM (23 February 2012). Metabolism of Drugs and Other Xenobiotics. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 302–. ISBN 978-3-527-64632-6. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- Anthony PK (2002). Pharmacology Secrets. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 39–. ISBN 978-1-56053-470-9.

- Cowen P, Harrison P, Burns T (9 August 2012). Shorter Oxford Textbook of Psychiatry. OUP Oxford. pp. 532–. ISBN 978-0-19-162675-3. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- Elks J (14 November 2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. pp. 889–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. 2000. pp. 48–. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1.

- Fagan T, Warden PG (1996). Historical Encyclopedia of School Psychology. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 307–. ISBN 978-0-313-29015-2.

- López-Muñoz F, Srinivasan V, de Berardis D, Álamo C, Kato TA (16 November 2016). Melatonin, Neuroprotective Agents and Antidepressant Therapy. Springer. pp. 374–. ISBN 978-81-322-2803-5.

- Martin A, Scahill L, Kratochvil C (14 December 2010). Pediatric Psychopharmacology. Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 292–. ISBN 978-0-19-539821-2.

- Sittig M (22 October 2013). Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Encyclopedia (3rd ed.). William Andrew Publishing, Elsevier. pp. 281–. ISBN 978-0-8155-1856-3.

- Brown, M., "Nick Drake: the fragile genius", The Daily Telegraph, 25 November 2014.

- Morton IK, Hall JM (6 December 2012). Concise Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents: Properties and Synonyms. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 15–. ISBN 978-94-011-4439-1. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017.

- "Amitriptyline". Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- "Amitriptyline International Brands". Drugs.com. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- Flament MF, Bissada H, Spettigue W (March 2012). "Evidence-based pharmacotherapy of eating disorders". International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 15 (2): 189–207. doi:10.1017/S1461145711000381. PMID 21414249.

- Mendelson WB, Roth T, Cassella J, Roehrs T, Walsh JK, Woods JH, Buysse DJ, Meyer RE (February 2004). "The treatment of chronic insomnia: drug indications, chronic use and abuse liability. Summary of a 2001 New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit meeting symposium". Sleep Med Rev. 8 (1): 7–17. doi:10.1016/s1087-0792(03)00042-x. PMID 15062207.

- Carneiro JP, Menezes A, Pinto SC (1 July 2017). "Alarme noturno e enurese: uma revisão baseada na evidência" [Nocturnal alarm therapy and enuresis: an evidence-based review]. Revista Portuguesa de Medicina Geral e Familiar. 33 (3): 200–208. doi:10.32385/rpmgf.v33i3.12162. ISSN 2182-5173.

- Sim Y-J, Kim J-M, Kwon S, Choe B-H (2009). "Clinical experience with amitriptyline for management of children with cyclic vomiting syndrome". Korean Journal of Pediatrics. 52 (5): 538–43. doi:10.3345/kjp.2009.52.5.538.

- Boles RG, Lovett-Barr MR, Preston A, Li BU, Adams K (2010). "Treatment of cyclic vomiting syndrome with co-enzyme Q10 and amitriptyline, a retrospective study". BMC Neurol. 10: 10. doi:10.1186/1471-2377-10-10. PMC 2825193. PMID 20109231.

- Arnold W (2006). "Functional biliary type pain syndrome". In Pasricha PJ, Willis WD, Gebhart GF (eds.). Chronic Abdominal and Visceral Pain. London: Informa Healthcare. pp. 453–62. ISBN 978-0-8493-2897-8.

- "Amitriptyline Hydrochloride Monograph for Professionals". Archived from the original on 24 September 2014. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- "Management of Gastroparesis | American College of Gastroenterology". Archived from the original on 18 June 2015. Retrieved 16 June 2015.

Further reading

- Dean L (March 2017). "Amitriptyline Therapy and CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 Genotype". In Pratt VM, McLeod HL, Rubinstein WS, et al. (eds.). Medical Genetics Summaries. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). PMID 28520380.