Anarchism and Esperanto

Anarchism and Esperanto are strongly linked because of their common ideals of social justice and equality. During the early Esperanto movement, anarchists enthusiastically publicized the language, and the two movements have much common history.

History

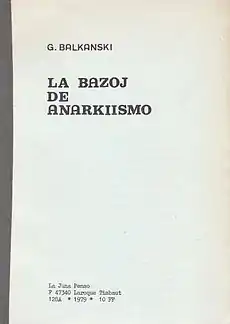

Anarchists were among the first to publicize Esperanto. In 1905, the first Esperanto anarchist group was founded. Many other followed: in Bulgaria, China, and other countries. Anarchists and anarcho-syndicalists, who before the first world war belonged to the largest group between proletarian Esperantists, founded Paco-Libereco,[1] an international league which published the newspaper Internacia Socia Revuo (International Society Review). Paco-Libereco merged with another progressive association, Esperantista Laboristaro (Esperanto Workers). The new organization was called Liberiga Stelo (Freeing Star).[2] Until 1914, it published much revolutionary literature in Esperanto, some related to anarchism. In this way a lively collection of correspondence evolved between anarchists in different countries, for example, between European and Japanese anarchists. In 1907, the international anarchist convention in Amsterdam made a resolution about international languages, and during the following years similar resolutions came. Esperantists who participated in the convention were principally occupied with international relations between anarchists.

In March 1925, the Berlin Group of Anarcho-syndicalist Esperantists in Amsterdam welcomed the second conference of the International Workers' Association (IWA). They spoke about how Esperanto in the ranks of the German IWA-section FAUD "already took root to the degree that it now founded a world organization of Esperantists on freedom-counter-authority fundamentals." That is an allusion to the World League of Esperantists Without a State, which was founded in 1920, because the World Anational Association (Sennacieca Asocio Tutmonda) was strongly under communist influence. It seemed that the World League of Esperantists Without a State was fused into the World Anational Association afterwards.

The chief strength of the worker's Esperanto movement was in Germany and the Soviet Union. Between them, they founded the International Science Anarchist Library of International Language in Soviet Ukraine. That group published the book Etiko by Kropotkin, the Anarkiismo by Borovoi and other works for international reading in Esperanto. Anarchist Esperantists focused their work at the time in East Asia, China, and Japan. In those countries, Esperanto was soon made a popular thing between anarchists. They published many newspapers, most often in two languages. For example, from 1913, Liu Shifu, who wrote as Sifo, published the newspaper La Voĉo de l'Popolo. It was the first anarchist newspaper in China. In the beginning, the information in its Chinese language part came mostly from the above-mentioned Internacia Socia Revuo. Liu Shifu died in 1915. There were also many anarchists and socialists among the first Japanese Esperantists. They were many times eliminated and persecuted. For example, in 1931, the newspaper La Anarkiisto stopped appearing because its editorial team was sent to jail. The anarchist Esperantists survived significant losses during the persecution of Soviet Esperantists in 1937. Many anarchist Esperantists were murdered or sent away to labor camps.

Esperanto played a small roll in the International Brigades during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939). From 1936-1939, the Iberian League of Esperanto Anarchists published a weekly newsletter from Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT). The CNT radio station also broadcast Esperanto programs.

After the second world war, the Paris group was the first to restart organized labor. From 1946 it published the newspaper Senŝtatano (person without a country).[3] There was also an active anarchist group in Paris in the years following. In 1981, Radio Esperanto was founded, which still broadcasts one hour on the frequency of Radio Libertaire today. Most of the liberationists and anarchists were organized in the World Anational Association afterwards. In 1969, they started to publish the Liberecana Bulteno, which today is called Liberecana Ligilo.

See also

- Aleksander Nakov

- Nigra Fenikso

- Sifo

- Taiji Yamaga

- Eduardo Vivancos

References

- The Esperanto Movement (Contributions to the Sociology of Language), Peter G. Forster, ISBN 9027933995, paĝo 190

- Historio de S. A. T., 1921 1952,Paris, 1953, Eldoninto :SAT, 152 paĝoj

- Javier Alcalde, "Eduardo Vivancos kaj la liberecana Esperanto", afterword to a bilingual edition of Eduardo Vivancos, Unu lingvo por ĉiuj: Esperanto, Calúmnia, 2019, p.77-91.

Bibliography

- Historio de Esperanto, Aleksander Korĵenkov, Kaliningrado, 2005, Chapter 9

- Esperanto & Anarchism. A universal language, Xavi Alcalde, Fifth Estate # 400, Spring, 2018.

External links

- Esperanto kaj Anarkiismo

- Ekrigardo al la anarkista partopreno en la esperantista movado

- STATUTOJ ILA (Internacia Laborista Asocio)

- AL LA BARICADOJ

- KIO ESTAS NKL ?

- KIO ESTAS LA ANARKI-SINDIKATISMO ?

- La lingvo de libereco - La voĉo de internaciismo - Traduko de artikolo el "Organise!" No 55 - 2001 kun aldonitaj reagoj.