And babies

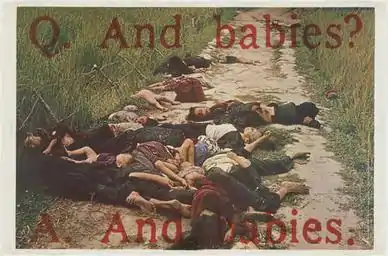

And babies (December 26, 1969[2]) is an iconic anti-Vietnam War poster.[1] It is a famous example of "propaganda art"[3] from the Vietnam War that uses the now infamous color photograph of the My Lai Massacre taken by U.S. combat photographer Ronald L. Haeberle on March 16, 1968. It shows about a dozen dead and partly naked South Vietnamese women and babies in contorted positions stacked together on a dirt road, killed by U.S. forces. The picture is overlaid in semi-transparent blood-red lettering that asks along the top "Q. And babies?", and at the bottom answers "A. And babies." The quote is from a Mike Wallace CBS News television interview with U.S. soldier Paul Meadlo, who participated in the massacre. The lettering was sourced from The New York Times,[4] which printed a transcript of the Meadlo interview the day after.[5]

According to cultural historian M. Paul Holsinger, And babies was "easily the most successful poster to vent the outrage that so many felt about the conflict in Southeast Asia."[1]

History

- Q. So you fired something like sixty-seven shots?

- A. Right.

- Q. And you killed how many? At that time?

- A. Well, I fired them automatic, so you can't – You just spray the area on them and so you can’t know how many you killed ‘cause they were going fast. So I might have killed ten or fifteen of them.

- Q. Men, women, and children?

- A. Men, women, and children.

- Q. And babies?

- A. And babies.

In 1969, the Art Workers Coalition (AWC), a group of New York City artists who opposed the war, used Haeberle's shocking photograph of the My Lai Massacre, along with a disturbing quote from the Wallace/Meadlo television interview,[6][7] to create a poster titled And babies.[1] It was produced by AWC members Irving Petlin, Jon Hendricks and Frazer Dougherty along with Museum of Modern Art members Arthur Drexler and Elizabeth Shaw.[1] The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) had promised to fund and circulate the poster, but after seeing the 2 by 3 foot poster, pulled financing for the project at the last minute.[2][8] MoMA's Board of Trustees included Nelson Rockefeller and William S. Paley (head of CBS), who reportedly "hit the ceiling" on seeing the proofs of the poster.[2] Both were "firm supporters" of the war effort and backed the Nixon administration.[2] It is unclear if they pulled out for political reasons (as pro-war supporters), or simply to avoid a scandal (personally and/or for MoMA), but the official reason, stated in a press release, was that the poster was outside the "function" of the museum.[2] Nevertheless, under the sole sponsorship of the AWC, 50,000 posters were printed by New York City's lithographers union.

On December 26, 1969, a grassroots network of volunteer artists, students and peace activists began circulating it worldwide.[2][8] Many newspapers and television shows re-printed images of the poster, consumer poster versions soon followed, and it was carried in protest marches around the world, all further increasing its viewership. In a further protest of MoMA's decision to pull out of the project, copies of the poster were carried by members of the AWC into the MoMA and unfurled in front of Picasso's painting Guernica – on loan to MoMA at the time, the painting depicts the tragedies of war and the suffering it inflicts upon innocent civilians.[2] One member of the group was Tony Shafrazi, who returned in 1974 to spray paint the Guernica with the words "KILL LIES ALL" in blood red paint, protesting about Richard Nixon's pardon of William Calley for the latter's actions during the My Lai massacre.[9]

Although the photograph was shot almost two years prior to the production of the poster, Haeberle had not released it until late 1969. It was a color photograph taken on his personal camera, which he did not turn over to the military, unlike the black and white photographs he took on a military camera. Haeberle sold the color photographs to Life magazine where they were first seen nationally in the December 5, 1969, issue.[2] When the poster came out a few weeks later, in late December 1969, the image was still quite shocking and new to most viewers but already becoming the iconic image of the My Lai Massacre and U.S. war crimes in Vietnam.[4]

The implied message of the poster was that in Vietnam, babies were enemy combatants, i.e., the war was immoral. The epithet, "baby killers", was often used by anti-war activists against U.S. soldiers, largely as a result of the My Lai Massacre.[10] Although Vietnam soldiers had been called "baby killers" since at least 1966, My Lai and the Haeberle photographs further solidified the stereotype of drug-addled soldiers who killed babies. According to cultural historian M. Paul Holsinger, And babies was "easily the most successful poster to vent the outrage that so many felt about the conflict in Southeast Asia. Copies are still frequently seen in retrospectives dealing with the popular culture of the Vietnam War era or in collections of art from the period."[1] According to historian Matthew Israel, "My Lai became the representative incident of war crimes in Vietnam. It sparked a great deal of antiwar protest, including efforts by artists, the best-known of which was the And babies poster."[4]

The poster was included in two major MoMA exhibitions: Kynaston McShine's 1970 exhibition of conceptual art, Information; and Betsy Jones' 1971 The Artist as Adversary.[4]

During the 1972 Nixon reelection campaign, the poster was revived with the text replaced with "Four More Years?" in blood red.[4] The British punk band Discharge wrote the song "Q: And Children? A: And Children" on the album Hear Nothing See Nothing Say Nothing (1982).

References

- M. Paul Holsinger (1999). "And Babies". War and American Popular Culture. Greenwood Press. p. 363.

- Francis Frascina (1999). Art, politics, and dissent: aspects of the art left in sixties America. pp. 175–186+. ISBN 978-0719044694. Archived from the original on 2018-05-29. discuss the creation of the poster.

- Daniel Cooper (2003). "Art". In Nicholas John Cull (ed.). Propaganda and Mass Persuasion: A Historical Encyclopedia, 1500 to the Present. ABC-CLIO. p. 23.

Propaganda art found more fertile ground in criticizing the U.S. government during the Vietnam conflict through works such as the famous Art Workers Coalition piece Q. And Babies? A. And Babies (1970) which commented on the horrors of the My Lai incident.

The poster is also discussed in Propaganda Prints: A History of Art in the Service of Social and Political Change (2011), p. 181, and Why America Fights: Patriotism and War Propaganda from the Philippines to Iraq (2009), p. 221 - Matthew Israel (2013). Kill for Peace: American Artists Against the Vietnam War. University of Texas Press. pp. 121–127.

- Meadlo-Wallace interview transcript 1969. Internet Archive. November 24, 1969. Retrieved May 28, 2014.

- Michael W. Eysenck (2004). Psychology: An International Perspective. p. 723. ISBN 978-1841693606.

- Stanley Milgram (2009). Obedience to Authority: An Experimental View. HarperCollins. pp. 183–186. ISBN 978-0061765216.

- Peter Howard Selz; Susan Landauer (2006). Art of engagement: visual politics in California and beyond. p. 46. ISBN 978-0520240520.

- J. Hoberman (13 December 2004). "Pop and Circumstance". The Nation. pp. 22–26. Archived from the original on 19 March 2005.

- Myra MacPherson (2009). Long time passing: Vietnam and the haunted generation. p. 497. ISBN 978-0253002761. Archived from the original on 2018-05-29.

... veterans were stamped 'baby killers' largely as a result of the My Lai Massacre....

Further reading

- Matthew Israel (2013). "Chapter 6: 1969. AWC, Dead Babies, Dead American Soldiers". Kill for Peace. pp. 119–127.

- Lucy Lippard (1990). A Different War: Vietnam in Art. Seattle. pp. 27–28.