Ann Jellicoe (educationalist)

Anne Jellicoe, née Anne William Mullin (1823–1880) was a noted Irish educationalist best known for the founding of the prestigious Alexandra College, which became a force in women's education under her management.

Anne Jellicoe | |

|---|---|

| Born | Anne William Mullin 26 March 1823 Mountmellick, County Laois, Ireland |

| Died | 18 October 1880 (aged 57) Birmingham, United Kingdom |

| Nationality | Irish |

| Occupation | Educationalist |

| Known for | Founding Alexandra College |

Early life

She was born on 23 March 1823 at Mountmellick, County Laois to William and Margaret Mullin (née Thompson), and had one brother John William Mullin. Her father was a Quaker schoolmaster who ran his own school for boys, with emphasis on higher learning, including English, history, the classics, and higher mathematics.[1] Anne married John Jellicoe, a flour miller on 28 October 1846 in Mountmellick[1][2] and moved to Clara, County Offaly two years later.

Educational work

There is no record of where Jellicoe was educated as a child. She was active in charitable works from an early age. Johanna Carter, who was a teacher at a school for girls in the village, became a role model for Jellicoe. Carter provided vocational training for girls at her school and invented Mountmellick Embroidery, proving to Jellicoe that work could liberate women.[3] In Clara she set up an embroidery and lace school to provide employment for young girls.[4] She not only encourage the women to create products for market, she also encouraged them to cultivate their minds and become independent. The Catholic church didn't agree with this type of education. So much so that the parish priest came to the school and broke it up. The school continued to flourish until 1856, even without the support of the church.[3]

The Jellicoes moved to Dublin in 1858 where she helped revive Cole Alley Infant School for poor children of all religions run by the Quakers.[5] With support of the Dublin Statistical Society, established in 1847 to tackle social problems, Jellicoe developed observation and research techniques that she used to investigate prisons, slums and workplaces in Dublin. She was asked to present a paper at the 1861 meeting of the National Association for the Promotion of Social Science on the conditions of women working in factories in Dublin.[3] She collected data on wages, working conditions and advancement opportunities. She concluded that women employed in these institutions were helpless working in insecure positions. She spoke to pillars of society on the importance of educating the working class by establishing infants schools and evening schools for older girls.

On 19 August 1861 Jellicoe, along with Barbara Corlett, founded the Dublin branch of London-based Society for Promoting the Employment of Women to educate women for work outside the home.[3] The response to the Society was overwhelming. In the first couple of years over 500 women registered for classes with the Society.[3] Jellicoe quickly found that the gentlewomen attending the courses thought working for wages was taboo and social suicide. This prompted her to found a new employment society Queen's Institute. The classes provided by the Institute focused on practical skills such as bookkeeping, secretarial skills and sewing-skills that would result in employment. Potential employers began to show an interest in Institute graduates, most prominently the Irish Magnetic Telegraph Company, which provided equipment and its head engineer as a teacher.[3]

Jellicoe's work with the Institute led her to realise that women must be educated before they could be trained. She was widowed in 1862, and using her £3000 inheritance, she financed a more permanent home for the Queen's Institute.[5] In 1866, with the help of Archbishop Chenevix Trench, she founded Alexandra College, Dublin, the first women's college in Ireland to aim at a university type education. The college was named in honour of the then Princess of Wales.[5] The College offered advanced education for women with classes offered in Greek, Latin, Algebra, Philosophy and Natural Sciences among others.[3] Her foundation of the Governess Association of Ireland followed in 1869[4] and Alexandra School, a secondary school attached to Alexandra College, was founded in 1873.[6]

Publications

- 'Woman's supervision of women's industry' (1861) Transactions of the National Association for the Promotion of Social Science

- 'Visit to the female convict prison at Mountjoy, Dublin' (1862) Transactions of the National Association for the Promotion of Social Science

Death and legacy

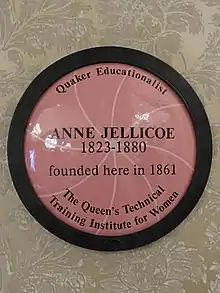

The Jellicoes had no children,[1] and John died in 1862.[7] Anne died suddenly in Birmingham whilst visiting her brother on 18 October 1880 aged 57 and she is buried at the Friends' burial-ground at Rosenallis.[1] The Queen's Institute did not last long after her death, closing its doors in 1881.[3] There are two portraits of Anne in Alexandra College, and a memorial tablet to both John and Anne in the Chapel of Mt Jerome cemetery, Harold's Cross, Dublin.[1] There is a plaque dedicated to Anne at the site of the Queen's Institute, which is now Buswells Hotel, erected by the National Committee for Commemorative Plaques in Science and Technology.[8]

References

- Parkes, Susan M. "Jellicoe, Anne". Dictionary of Irish Biography. RIA and Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- Ireland, Civil Registration Marriages Index 1845–1958

- Mulvihill, edited by Mary (2009). Lab coats and lace : the lives and legacies of inspiring Irish women scientists and pioneers. Dublin: WITS (Women in Technology & Science). ISBN 9780953195312.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Bourke, Angela (2002). The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing, Volume 5. New York: NYU Press. p. 763. ISBN 9780814799079.

- Rappaport, Helen (2001). Encyclopedia of Women Social Reformers, Volume 1. California: ABC-CLIO. pp. 335–336. ISBN 9781576071014.

- O'Connor, Anne V. "Anne Jellicoe". in Mary Cullen & Maria Luddy (eds.), Women, Power and Consciousness, Dublin, 1995.

- Freemans Journal of 27 December 1862

- Ask About Ireland. "Irish Scientists". Ask About Ireland. Retrieved 16 April 2015.