Anthony Hungerford of Black Bourton

Sir Anthony Hungerford (1567–1627) of Black Bourton in Oxfordshire, Deputy Lieutenant of Wiltshire until 1624, was a religious controversialist.

Origins

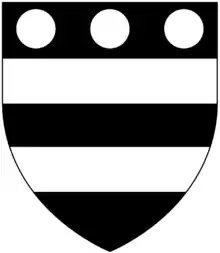

Hungerford was born in 1567 at Great Bedwyn in Wiltshire,[1] the son of Anthony Hungerford (died 1589) of Down Ampney in Gloucestershire, a descendant of Sir Edmund Hungerford, second son of Walter Hungerford, 1st Baron Hungerford of Farleigh and Heytesbury. His mother was Bridget Shelley, daughter of John Shelley, and granddaughter of Sir William Shelley, Justice of the Common Pleas.[2] His father was a Puritan, but his mother was a devout Roman Catholic, the religion in which Hungerford was raised.[1]

Career

On 12 April 1583 aged 16, Hungerford matriculated at St John's College, Oxford, which he left without taking a degree.[3][1][lower-alpha 1] However he was granted the degree of M.A. on 9 July 1594.[4][1] After being uncertain regarding his religious beliefs and Catholic upbringing, in 1588 at the time of the Spanish Armada and the threat from Catholic Spain, Hungerford embraced the reformed religion. He was knighted on 15 February 1608,[5] and served as a Deputy Lieutenant of Wiltshire until 1624, when he resigned the office in favour of his son Edward.[6] He was elected Member of Parliament for Marlborough in Wiltshire, for Queen Elizabeth I's 8th Parliament in 1593, and sat for Great Bedwyn, Wiltshire, in the next three consecutive Parliaments, in 1597, 1601, and the first Parliament of King James I in 1604.[1]

Marriages and children

Hungerford married twice:

- Firstly to Lucy Hungerford, a daughter of Sir Walter Hungerford (died c.1596) of Farleigh Castle in Wiltshire, by whom he had children including:[7] [lower-alpha 2]

- Sir Edward Hungerford (1596–1648), eldest son and heir, a Roundhead commander during the Civil War.[7]

- Bridget Hungerford, who married three times, firstly to Alexander Chocke (1594–1625) of Shalbourne,[8] secondly to John Rudhale and thirdly to John Vaughan, of Herefordshire, a Roman Catholic.[9]

- Secondly he married Sarah Crouch, daughter of John Crouch of the City of London, by whom he had four further children, two sons and two daughters including:[7][1]

- Anthony Hungerford, a Cavalier during the Civil War.

- John Hungerford.

Death and burial

He died in late June 1627 and was buried in Black Bourton Church.[6]

Writings

Some of his writings were published posthumously at Oxford in 1639 by his son Edward, including:

- "The advice of a son professing the religion established in the present church of England to his dear mother, a Roman catholic".

- "The memorial of a father to his dear children, containing an acknowledgement of God'? great mercy in bringing him to the profession of the true religion at this present established in the church of England", completed at Black Bourton in April 1627.[6][10]

Notes

- It is not clear if he went down from Oxford because of family financial difficulties, or because of his admittance to the Roman Catholic church.[1]

- The sources vary over the number of children Henry Lancaster states in the ODNB (published in 2009) "The couple had one son, Edward Hungerford (1596–1648) and two daughters before Lucy died on 4 June 1598", but in The history of Parliament (published 2010) he states "Bridget, Hungerford’s only daughter from his first marriage, married Alexander Chocke".

- Lancaster 2009.

- Hardy 1891, p. 253 cite:Le Neve, Pedigrees of Knights, p. 33.

- Hardy 1891, p. 253 cites: Oxford Univ. Reg., Oxford Hist. Soc.,n. ii. 126.

- Hardy 1891, p. 253 cites: Oxford Univ. Reg., II. i. 235.

- Hardy 1891, p. 253 cites: Metcalfe, p. 159.

- Hardy 1891, p. 253.

- Hardy 1891, pp. 253–254.

- Lancaster 2010.

- Lancaster 2010a.

- Roberts 1901, pp. 292–307.

References

- Lancaster, Henry (May 2009) [2004]. "Hungerford, Sir Anthony (bap. 1567, d. 1627)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/14170. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Lancaster, Henry (2010). "Hungerford, Anthony (1567–1627), of Stock, nr. Great Bedwyn, Wilts. and Down Ampney, Glos.; later of Black Bourton, Oxon.". In Thrush, Andrew; Ferris, John P. (eds.). The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1604–1629, ed. Cambridge University Press.

- Lancaster, Henry (2010a). "Chocke, Alexander II (1593/4-1625), of Shalbourne, Wilts.; later of Hungerford Park, Berks.". In Thrush, Andrew; Ferris, John P. (eds.). The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1604–1629.

- Roberts, Laura M. (April 1901). "Sir Anthony Hungerford's 'Memorial". The English Historical Review. Oxford University Press. 16 (62): 292–307. doi:10.1093/ehr/xvi.lxii.292. JSTOR 548654.

Attribution

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Hardy, William John (1891). "Hungerford, Anthony (1564–1627)". In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. 28. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 253, 254. Endnotes

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Hardy, William John (1891). "Hungerford, Anthony (1564–1627)". In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. 28. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 253, 254. Endnotes

- Wood's Athenae Oxon. ed. Bliss, ii. 410-11

- Brit. Mus. Cat.

- Hoare's Hungerfordiana, 1823

- Le Neve's Pedigrees of Knights (Harl. Soc.),pp. 33–4.