Antonio Fantuzzi

Antonio Fantuzzi (active in the 1540s) was an Italian painter and printmaker active in the French Renaissance in a Mannerist style. All that is known about his early life is that he was born in Bologna, from the accounts at Fontainebleau and one inscription on a print (see illustration).[1]

He is recorded as a painter of the First School of Fontainebleau from 1537 into the 1540s, at first on "modest wages", but from 1540 better paid, and apparently a principal assistant to Francesco Primaticcio, who had taken charge of the "school" decorating the Palace of Fontainebleau after the suicide in 1540 of Rosso Fiorentino. Primaticcio was also Bolognese, and may well have summoned Fantuzzi to France in 1537, although he may well have only completed his training in France.[2] He became a leading member of the printmaking workshop at Fontainebleau and nearly 100 etchings survive,[3] 16 dated between 1542 and 1545. Most copy designs by Rosso (about 25), Giulio Romano (21 at least), or Primaticcio.[4] He is last recorded at Fontainebleau in 1550.[5]

In the past, art historians often confused him with Antonio da Trento, another north Italian at Fontainebleau, but the two identities have now been securely disentangled by Henri Zerner;[6] da Trento specialized in chiaroscuro woodcuts, a technique also used by Fantuzzi, and used to be assigned Fantuzzi's prints, partly because their monograms are similar.[7]

Works

No identifiable painting or drawing by him survives; his first task at Fontainebleau was helping with the room over the "Porte Dorée", and after 1540 the "Gallery of Ulysses". Neither sets of decorations has survived, and Fantuzzi's prints are valuable in recording some of the designs.[8] He is also recorded as being, from 1540, in charge of the supply of designs for decorative elements such as grotesques to the other artists.[9] His prints of ornament designs are "particularly appealing, perhaps because they correspond with his specialty in painting. He seems to have lavished more care and to have had sympathies in these works not usually felt in his figural prints after Rosso".[10] From 1540 his salary increased from seven to twenty livres per month.[11]

He worked closely with Léon Davent, a French native who was one of the other leading Fontainebleau printmakers, who had presumably trained as a goldsmith and so an engraver. It is thought that Fantuzzi taught Davent the artist's technique of etching, which once learned became Davent's main technique. In return Fantuzzi adopted a number of technical tricks developed by engravers and translatable to etching, very likely with instruction from Davent.[12] His early style is "rather brutal in appearance" when copying Giulio Romano, and "angular and restless" when copying Rosso Fiorentino, but he moved to a gentler and more harmonious style closer to Primaticcio.[13] Suzanne Boorsch says that his early style was "full of energy but lacked discipline, so that in some of the prints a violent light and strokes in many directions cause figures and grounds to be confused... His later works retain this liveliness but are calmer and more controlled".[14]

The example illustrated of a copy of a stucco and paint surround at the palace was presumably made from the preparatory drawing; the frame surrounded a painting of Ignorance Vanquished and allegory of "The Enlightenment of François I" by Rosso Fiorentino. The landscape here has just been inserted from some other source; presumably the drawing used had a blank space here. Apart from the initials, which stand for François, Roi de France, the print is in reverse (a mirror image) of the frame in the Gallery of François I in the palace,[15] which survives, though it is different in some details, and has a very different effect having both elements in sculpted stucco and in paint. There are a number of other etchings by Fantuzzi and others of the very complex frames in the gallery, all showing similar differences and inserted landscapes, indicating that they were following drawings prepared before the final designs were achieved. Other prints record the paintings actually placed inside the frames.[16]

The "mildly licentious" lunette Mars and Venus Bathing of about 1543 was probably copying a painting by Primaticcio for the six-room "Appartement des Bains" (Bathroom Suite) at the palace, decorated in the 1540s and destroyed in 1697.[18][19] Cassiano del Pozzo recorded that one of the rooms there featured painted lunettes, though of Diana and Callisto. It may have been made from a drawing now in the Louvre of the same size but in reverse; this used to be attributed to Rosso, but is now given to Primaticcio.[20]

In 2003 Fantuzzi and Davent shared an exhibition in the Cabinet des Estampes in Geneva: Les Lumières du maniérisme français: Antonio Fantuzzi et Léon Davent, 1540–1550 ("Leaders of French Mannerism: Antonio Fantuzzi and Léon Davent, 1540–1550").[21]

The Fontainebleau workshop

Although there is no certain proof, most scholars have agreed that there was a printmaking workshop at the Palace of Fontainebleau itself, reproducing the designs of the artists for their works in the palace, as well as other compositions they produced, and copying from drawings by other masters brought from Italy, probably mainly by Primaticcio.[22] The most productive printmakers were Davent, Fantuzzi, and Jean Mignon, followed by the "mysterious" artist known from his monogram as "Master I♀V" (♀ being the alchemical symbol for copper, from which the printing plates were made).[23] The workshop seems to have been active between about 1542 and 1548 at the latest; Francis I of France died in March 1547, after which funding for the palace wound down, and the school dispersed. Hundreds of etchings were produced;[24] these were the first etchings made in France, and not far behind the first Italian uses of the technique, which originated in Germany.[25] The earliest impressions of all the Fontainebleau prints are in brown ink, and their intention seems to have been essentially reproductive.[26]

The intention of the workshop was to disseminate the new style developing at the palace more widely, both to France and to the Italians' peers back in Italy. Whether the initiative to do this came from the king or another patron, or from the artists alone, is unclear. David Landau believes that Primaticcio was the driving force;[27] he had stepped up to become the director of the work at Fontainebleau after the suicide (if Vasari is believed) of Rosso Fiorentino in 1540.[28]

The enterprise seems to have been "just slightly premature" in terms of catching a market.[29] The etched prints were often marked by signs of the workshop's inexperience and sometimes incompetence with the technique of etching, and according to Sue Welsh Reed: "Few impressions survive from these plates, and it is questionable whether many were pulled. The plates were often poorly executed and not well printed; they were often scratched or not well polished and did not wipe clean. Some may have been made of metals soft as copper, such as pewter."[30] A broadening market for prints preferred the "highly finished textures" of Nicolas Beatrizet, and later "proficient but ultimately uninspired" engravers such as René Boyvin and Pierre Milan.[31]

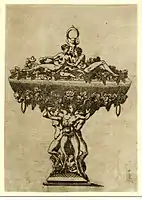

Design for metalwork

Design for metalwork Gladiators fighting in an arena, with soldiers watching. c.1542/43 Etching after Giulio Romano's design for the ceiling of the Sala dei venti, Palazzo del Te, Mantua

Gladiators fighting in an arena, with soldiers watching. c.1542/43 Etching after Giulio Romano's design for the ceiling of the Sala dei venti, Palazzo del Te, Mantua

The Continence of Scipio: Scipio, in Roman armour, giving the woman back to her husband kneeling on the left. 1543 Etching after Giulio Romano

The Continence of Scipio: Scipio, in Roman armour, giving the woman back to her husband kneeling on the left. 1543 Etching after Giulio Romano God with Angels

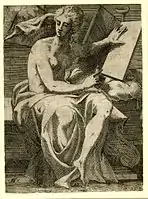

God with Angels Sibyl, c.1544/45 Etching after Francesco Primaticcio

Sibyl, c.1544/45 Etching after Francesco Primaticcio The Unity of the State: Roman ruler in richly decorated armour, with pomegranate in his hand, standing surrounded by people. c.1543 Etching after Rosso Fiorentino

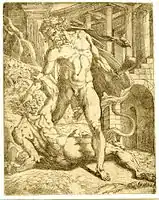

The Unity of the State: Roman ruler in richly decorated armour, with pomegranate in his hand, standing surrounded by people. c.1543 Etching after Rosso Fiorentino Hercules standing in an architectural setting, and grabbing the head of a man lying at his feet. c.1543 Etching after Rosso Fiorentino.[34]

Hercules standing in an architectural setting, and grabbing the head of a man lying at his feet. c.1543 Etching after Rosso Fiorentino.[34]

Notes

- Boorsch, 471

- Boorsch, 84

- Benezit; Reed, 29; Zerner and Boorsch, 471 both say over 100.

- Boorsch, 471

- Reed, 27; Benezit

- Zerner; but see Reed 28 note 2 for dissenters in 1962 (Zava-Boccazzi, in further reading) and 1971

- Benezit

- Boorsch, 471; Reed, 27

- Boorsch, 471; Benezit

- Reed, 28

- Boorsch, 84

- Reed, 27, 31; Benezit

- Reed, 27 (quoted); Benezit; Zerner

- Boorsch, 85

- Boorsch, 239–241; Reed, 28

- Boorsch, 236–240

- Boorsch, 247

- Boorsch, 247

- "Collection Online". The British Museum. Retrieved 8 February 2017.

- Boorsch, 247

- Benezit

- Boorsch, 80–83; Reed, 27

- Boorsch, 80–83

- Reed, 27

- Boorsch, 80–81; Landau, 308–309

- Boorsch, 80–81; Reed, 27

- Boorsch, 95; Landau, 309

- Boorsch, 79

- Landau, 309

- Reed, 27

- Landau, 309

- As described by the British Museum: "the goddess, standing on the left next to the olive tree with Hermes on her side, is already crowned by Nike; on the right, Poseidon is holding the horse; in the upper part, an assembly of gods attending the contest".

- Boorsch, 238

- Boorsch, 245–246

References

- Benezit Dictionary of Artists, "FANTUZZI, Antonio.", Oxford Art Online, Oxford University Press, accessed January 8, 2017, Subscription required

- Boorsch, Suzanne, in: Jacobson, Karen (ed), (often wrongly cat. as George Baselitz), The French Renaissance in Prints, 1994, Grunwald Center, UCLA, ISBN 0962816221

- Landau, David, in Landau, David, and Parshall, Peter, The Renaissance Print, Yale, 1996, ISBN 0300068832

- Reed, Sue Welsh, in: Reed, Sue Welsh & Wallace, Richard (eds), Italian Etchers of the Renaissance and Baroque, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston 1989, ISBN 0-87846-306-2 or 304-4 (pb)

- Zerner, Henri, "Fantuzzi, Antonio", Grove Art Online, Oxford Art Online, Oxford University Press, accessed January 8, 2017, Subscription required

Further reading

- F. Zava-Boccazzi, Antonio da Trento, incisore, Trent, 1962.

- H. Zerner, "L'Eau-forte à Fontainebleau: Le Rôle de Fantuzzi", Art de France: Revue annuelle de l'art ancien et moderne, iv (1964), pp. 70–85.

- Zerner, Henri: École de Fontainebleau, Gravures, Arts et métiers graphiques, Paris, 1969.

- Brugerolles, Emmanuelle/Strasser, Nathalie/Mason, Rainer Michael (ed.)/Baselitz, Georg: La Bella maniera. Gravures maniéristes de la collection Georg Baselitz, École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts, Paris, 2002.

- Rosso Fiorentino (exh. cat. by E. Carroll, Washington, DC, N.G.A., 1987)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Antonio Fantuzzi. |