Antonio Vivaldi

Antonio Lucio Vivaldi (UK: /vɪˈvældi/, US: /vɪˈvɑːldi, -ˈvɔːl-/;[2][3][4][5] Italian: [anˈtɔːnjo ˈluːtʃo viˈvaldi] (![]() listen); 4 March 1678 – 28 July 1741) was an Italian[6] Baroque composer, virtuoso violinist, teacher, impresario, and Roman Catholic priest. Born in Venice, the capital of the Venetian Republic, Vivaldi is regarded as one of the greatest Baroque composers, and his influence during his lifetime was widespread across Europe, being paramount in the development of Johann Sebastian Bach's instrumental music. He composed many instrumental concertos, for the violin and a variety of other musical instruments, as well as sacred choral works and more than forty operas. His best-known work is a series of violin concertos known as the Four Seasons.

listen); 4 March 1678 – 28 July 1741) was an Italian[6] Baroque composer, virtuoso violinist, teacher, impresario, and Roman Catholic priest. Born in Venice, the capital of the Venetian Republic, Vivaldi is regarded as one of the greatest Baroque composers, and his influence during his lifetime was widespread across Europe, being paramount in the development of Johann Sebastian Bach's instrumental music. He composed many instrumental concertos, for the violin and a variety of other musical instruments, as well as sacred choral works and more than forty operas. His best-known work is a series of violin concertos known as the Four Seasons.

Many of his compositions were written for the all-female music ensemble of the Ospedale della Pietà, a home for abandoned children. Vivaldi had worked there as a Catholic priest for 18 months and was employed there from 1703 to 1715 and from 1723 to 1740. Vivaldi also had some success with expensive stagings of his operas in Venice, Mantua and Vienna. After meeting the Emperor Charles VI, Vivaldi moved to Vienna, hoping for royal support. However, the Emperor died soon after Vivaldi's arrival, and Vivaldi himself died in poverty less than a year later.

After almost two centuries of decline, Vivaldi's music underwent a revival in the early 20th century, with much scholarly research devoted to his work. Many of Vivaldi's compositions, once thought lost, have been rediscovered - in one case as recently as 2006. His music remains widely popular in the present day and is regularly played the world over.

Life

Childhood

Antonio Lucio Vivaldi was born on 4 March 1678 in Venice,[7] then the capital of the Venetian Republic. He was baptized immediately after his birth at his home by the midwife, which led to a belief that his life was somehow in danger. Though the reasons for the child's immediate baptism are not known for certain, it was done most likely due either to his poor health or to an earthquake that shook the city that day. In the trauma of the earthquake, Vivaldi's mother may have dedicated him to the priesthood.[8] The ceremonies which had been omitted were supplied two months later.[9]

Vivaldi's parents were Giovanni Battista Vivaldi and Camilla Calicchio, as recorded in the register of San Giovanni in Bragora.[10] Vivaldi had five known siblings: Bonaventura Tomaso Vivaldi, Margarita Gabriela Vivaldi, Cecilia Maria Vivaldi, Francesco Gaetano Vivaldi, and Zanetta Anna Vivaldi.[11] His father, Giovanni Battista, who was a barber before becoming a professional violinist, taught Antonio to play the violin and then toured Venice playing the violin with his young son. Antonio was probably taught at an early age, judging by the extensive musical knowledge he had acquired by the age of 24, when he started working at the Ospedale della Pietà.[12] Giovanni Battista was one of the founders of the Sovvegno dei musicisti di Santa Cecilia, an association of musicians.[13]

The president of the Sovvegno was Giovanni Legrenzi, an early Baroque composer and the maestro di cappella at St Mark's Basilica. It is possible that Legrenzi gave the young Antonio his first lessons in composition. The German scholar Walter Kolneder has discerned the influence of Legrenzi's style in Vivaldi's early liturgical work Laetatus sum (RV Anh 31), written in 1691 at the age of thirteen. Vivaldi's father may have been a composer himself: in 1689, an opera titled La Fedeltà sfortunata was composed by a Giovanni Battista Rossi—the name under which Vivaldi's father had joined the Sovvegno di Santa Cecilia.[14]

Vivaldi's health was problematic. One of his symptoms, strettezza di petto ("tightness of the chest"), has been interpreted as a form of asthma.[9] This did not prevent him from learning to play the violin, composing, or taking part in musical activities,[9] although it did stop him from playing wind instruments. In 1693, at the age of fifteen, he began studying to become a priest.[15] He was ordained in 1703, aged 25, and was soon nicknamed il Prete Rosso, "The Red Priest".[16] (Rosso is Italian for "red", and would have referred to the color of his hair, a family trait.)

Not long after his ordination, in 1704, he was given a dispensation from celebrating Mass most likely because of his ill health. Vivaldi said Mass as a priest only a few times, and appeared to have withdrawn from liturgical duties, though he remained a member of the priesthood. It is thought that this is also due to his habit of composing while performing mass. He seems to have remained committed to Catholicism, since the entry in the Vienna death records for him reads, "Antonio Vivaldi, Secular Priest".[17] It is thought that he remained a devout Catholic, indeed, in 1792, the Protestant composer Ernst Ludwig Gerber, wrote of the aged Vivaldi that "the rosary never left his hand except when he picked up the pen to write an opera".[18]

Ospedale della Pietà

In September 1703, Vivaldi became maestro di violino (master of violin) at an orphanage called the Pio Ospedale della Pietà (Devout Hospital of Mercy) in Venice.[7] While Vivaldi is most famous as a composer, he was regarded as an exceptional technical violinist as well. The German architect Johann Friedrich Armand von Uffenbach referred to Vivaldi as "the famous composer and violinist" and said that "Vivaldi played a solo accompaniment excellently, and at the conclusion he added a free fantasy [an improvised cadenza] which absolutely astounded me, for it is hardly possible that anyone has ever played, or ever will play, in such a fashion."[19]

Vivaldi was only 25 when he started working at the orphanage. Over the next thirty years he composed most of his major works while working there.[20] There were four similar institutions in Venice; their purpose was to give shelter and education to children who were abandoned or orphaned, or whose families could not support them. They were financed by funds provided by the Republic.[21] The boys learned a trade and had to leave when they reached the age of fifteen. The girls received a musical education, and the most talented among them stayed and became members of the Ospedale's renowned orchestra and choir.

Shortly after Vivaldi's appointment, the orphans began to gain appreciation and esteem abroad, too. Vivaldi wrote concertos, cantatas and sacred vocal music for them.[22] These sacred works, which number over 60, are varied: they included solo motets and large-scale choral works for soloists, double chorus, and orchestra.[23] In 1704, the position of teacher of viola all'inglese was added to his duties as violin instructor.[24] The position of maestro di coro, which was at one time filled by Vivaldi, required a lot of time and work. He had to compose an oratorio or concerto at every feast and teach the orphans both music theory and how to play certain instruments.[25]

His relationship with the board of directors of the Ospedale was often strained. The board had to take a vote every year on whether to keep a teacher. The vote on Vivaldi was seldom unanimous, and went 7 to 6 against him in 1709.[26] After a year as a freelance musician, he was recalled by the Ospedale with a unanimous vote in 1711; clearly during his year's absence the board had realized the importance of his role.[26] He became responsible for all of the musical activity of the institution[27] when he was promoted to maestro de' concerti (music director) in 1716.[28]

In 1705, the first collection (Connor Cassara) of his works was published by Giuseppe Sala:[29] his Opus 1 is a collection of 12 sonatas for two violins and basso continuo, in a conventional style.[24] In 1709, a second collection of 12 sonatas for violin and basso continuo appeared—Opus 2.[30] A real breakthrough as a composer came with his first collection of 12 concerti for one, two, and four violins with strings, L'estro armonico (Opus 3), which was published in Amsterdam in 1711 by Estienne Roger,[31] dedicated to Grand Prince Ferdinand of Tuscany. The prince sponsored many musicians including Alessandro Scarlatti and George Frideric Handel. He was a musician himself, and Vivaldi probably met him in Venice.[32] L'estro armonico was a resounding success all over Europe. It was followed in 1714 by La stravaganza (Opus 4), a collection of concerti for solo violin and strings,[33] dedicated to an old violin student of Vivaldi's, the Venetian noble Vettor Dolfin.[34]

In February 1711, Vivaldi and his father traveled to Brescia, where his setting of the Stabat Mater (RV 621) was played as part of a religious festival. The work seems to have been written in haste: the string parts are simple, the music of the first three movements is repeated in the next three, and not all the text is set. Nevertheless, perhaps in part because of the forced essentiality of the music, the work is considered to be one of his early masterpieces.

Despite his frequent travels from 1718, the Ospedale paid him 2 sequins to write two concerti a month for the orchestra and to rehearse with them at least five times when in Venice. The orphanage's records show that he was paid for 140 concerti between 1723 and 1733.

Opera impresario

In early 18th-century Venice, opera was the most popular musical entertainment. It proved most profitable for Vivaldi. There were several theaters competing for the public's attention. Vivaldi started his career as an opera composer as a sideline: his first opera, Ottone in villa (RV 729) was performed not in Venice, but at the Garzerie Theater in Vicenza in 1713.[36] The following year, Vivaldi became the impresario of the Teatro San Angelo in Venice, where his opera Orlando finto pazzo (RV 727) was performed. The work was not to the public's taste, and it closed after a couple of weeks, being replaced with a repeat of a different work already given the previous year.[32]

In 1715, he presented Nerone fatto Cesare (RV 724, now lost), with music by seven different composers, of which he was the leader. The opera contained eleven arias, and was a success. In the late season, Vivaldi planned to put on an opera entirely of his own creation, Arsilda, regina di Ponto (RV 700), but the state censor blocked the performance. The main character, Arsilda, falls in love with another woman, Lisea, who is pretending to be a man.[32] Vivaldi got the censor to accept the opera the following year, and it was a resounding success.

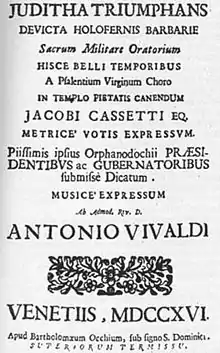

During this period, the Pietà commissioned several liturgical works. The most important were two oratorios. Moyses Deus Pharaonis, (RV 643) is now lost. The second, Juditha triumphans (RV 644), celebrates the victory of the Republic of Venice against the Turks and the recapture of the island of Corfu. Composed in 1716, it is one of his sacred masterpieces. All eleven singing parts were performed by girls of the orphanage, both the female and male roles. Many of the arias include parts for solo instruments—recorders, oboes, violas d'amore, and mandolins—that showcased the range of talents of the girls.[37]

Also in 1716, Vivaldi wrote and produced two more operas, L'incoronazione di Dario (RV 719) and La costanza trionfante degli amori e degli odi (RV 706). The latter was so popular that it performed two years later, re-edited and retitled Artabano re dei Parti (RV 701, now lost). It was also performed in Prague in 1732. In the years that followed, Vivaldi wrote several operas that were performed all over Italy.

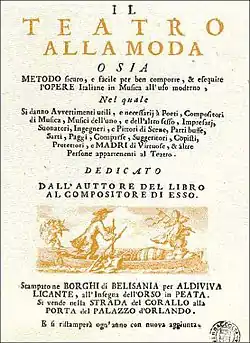

His progressive operatic style caused him some trouble with more conservative musicians such as Benedetto Marcello, a magistrate and amateur musician who wrote a pamphlet denouncing Vivaldi and his operas. The pamphlet, Il teatro alla moda, attacks the composer even as it does not mention him directly. The cover drawing shows a boat (the Sant'Angelo), on the left end of which stands a little angel wearing a priest's hat and playing the violin. The Marcello family claimed ownership of the Teatro Sant'Angelo, and a long legal battle had been fought with the management for its restitution, without success. The obscure text under the engraving mentions non-existent places and names: for example, ALDIVIVA is an anagram of "A. Vivaldi".

In a letter written by Vivaldi to his patron Marchese Bentivoglio in 1737, he makes reference to his "94 operas". Only around 50 operas by Vivaldi have been discovered, and no other documentation of the remaining operas exists. Although Vivaldi may have been exaggerating, it is plausible that, in his dual role of composer and impresario, he may have either written or been responsible for the production of as many as 94 operas—given that his career had by then spanned almost 25 years.[38] While Vivaldi certainly composed many operas in his time, he never attained the prominence of other great composers such as Alessandro Scarlatti, Johann Adolph Hasse, Leonardo Leo, and Baldassare Galuppi, as evidenced by his inability to keep a production running for an extended period of time in any major opera house.[39]

Mantua and the Four Seasons

In 1717 or 1718, Vivaldi was offered a prestigious new position as Maestro di Cappella of the court of prince Philip of Hesse-Darmstadt, governor of Mantua, in the northwest of Italy.[40] He moved there for three years and produced several operas, among them Tito Manlio (RV 738). In 1721, he was in Milan, where he presented the pastoral drama La Silvia (RV 734); nine arias from it survive. He visited Milan again the following year with the oratorio L'adorazione delli tre re magi al bambino Gesù (RV 645, now lost). In 1722 he moved to Rome, where he introduced his operas' new style. The new pope Benedict XIII invited Vivaldi to play for him. In 1725, Vivaldi returned to Venice, where he produced four operas in the same year.

During this period Vivaldi wrote the Four Seasons, four violin concertos that give musical expression to the seasons of the year. Though three of the concerti are wholly original, the first, "Spring", borrows motifs from a Sinfonia in the first act of Vivaldi's contemporaneous opera Il Giustino. The inspiration for the concertos was probably the countryside around Mantua. They were a revolution in musical conception: in them Vivaldi represented flowing creeks, singing birds (of different species, each specifically characterized), barking dogs, buzzing mosquitoes, crying shepherds, storms, drunken dancers, silent nights, hunting parties from both the hunters' and the prey's point of view, frozen landscapes, ice-skating children, and warming winter fires. Each concerto is associated with a sonnet, possibly by Vivaldi, describing the scenes depicted in the music. They were published as the first four concertos in a collection of twelve, Il cimento dell'armonia e dell'inventione, Opus 8, published in Amsterdam by Michel-Charles Le Cène in 1725.

During his time in Mantua, Vivaldi became acquainted with an aspiring young singer Anna Tessieri Girò, who would become his student, protégée, and favorite prima donna.[41] Anna, along with her older half-sister Paolina, moved in with Vivaldi and regularly accompanied him on his many travels. There was speculation as to the nature of Vivaldi's and Girò's relationship, but no evidence exists to indicate anything beyond friendship and professional collaboration. Vivaldi, in fact, adamantly denied any romantic relationship with Girò in a letter to his patron Bentivoglio dated 16 November 1737.[42]

Later life and death

At the height of his career, Vivaldi received commissions from European nobility and royalty. The serenata (cantata) Gloria e Imeneo (RV 687) was commissioned in 1725 by the French ambassador to Venice in celebration of the marriage of Louis XV. The following year, another serenata, La Sena festeggiante (RV 694), was written for and premiered at the French embassy as well, celebrating the birth of the French royal princesses, Henriette and Louise Élisabeth. Vivaldi's Opus 9, La cetra, was dedicated to Emperor Charles VI. In 1728, Vivaldi met the emperor while the emperor was visiting Trieste to oversee the construction of a new port. Charles admired the music of the Red Priest so much that he is said to have spoken more with the composer during their one meeting than he spoke to his ministers in over two years. He gave Vivaldi the title of knight, a gold medal and an invitation to Vienna. Vivaldi gave Charles a manuscript copy of La cetra, a set of concerti almost completely different from the set of the same title published as Opus 9. The printing was probably delayed, forcing Vivaldi to gather an improvised collection for the emperor.

Accompanied by his father, Vivaldi traveled to Vienna and Prague in 1730, where his opera Farnace (RV 711) was presented;[43] it garnered six revivals.[39] Some of his later operas were created in collaboration with two of Italy's major writers of the time. L'Olimpiade and Catone in Utica were written by Pietro Metastasio, the major representative of the Arcadian movement and court poet in Vienna. La Griselda was rewritten by the young Carlo Goldoni from an earlier libretto by Apostolo Zeno.

Like many composers of the time, Vivaldi faced financial difficulties in his later years. His compositions were no longer held in such high esteem as they once had been in Venice; changing musical tastes quickly made them outmoded. In response, Vivaldi chose to sell off sizeable numbers of his manuscripts at paltry prices to finance his migration to Vienna.[44] The reasons for Vivaldi's departure from Venice are unclear, but it seems likely that, after the success of his meeting with Emperor Charles VI, he wished to take up the position of a composer in the imperial court. On his way to Vienna, Vivaldi may have stopped in Graz to see Anna Girò.[45]

It is also likely that Vivaldi went to Vienna to stage operas, especially as he took up residence near the Kärntnertortheater. Shortly after his arrival in Vienna, Charles VI died, which left the composer without any royal protection or a steady source of income. Soon afterwards, Vivaldi became impoverished[47][48] and died during the night of 27/28 July 1741, aged 63,[49] of "internal infection", in a house owned by the widow of a Viennese saddlemaker. On 28 July, Vivaldi was buried in a simple grave in a burial ground that was owned by the public hospital fund. His funeral took place at St. Stephen's Cathedral. Contrary to popular legend, the young Joseph Haydn had nothing to do with his burial, since no music was performed on that occasion.[50] The cost of his funeral with a 'Kleingeläut' was 19 Gulden 45 Kreuzer which was rather expensive for the lowest class of peal of bells.

Vivaldi was buried next to Karlskirche, a baroque church in an area which is now part of the site of the TU Wien. The house where he lived in Vienna has since been destroyed; the Hotel Sacher is built on part of the site. Memorial plaques have been placed at both locations, as well as a Vivaldi "star" in the Viennese Musikmeile and a monument at the Rooseveltplatz.

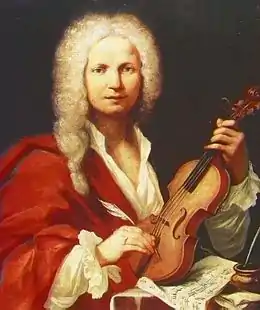

Only two, possibly three original portraits of Vivaldi are known to survive: an engraving, an ink sketch and an oil painting. The engraving, which was the basis of several copies produced later by other artists, was made in 1725 by François Morellon de La Cave for the first edition of Il cimento dell'armonia e dell'inventione, and shows Vivaldi holding a sheet of music.[51] The ink sketch, a caricature, was done by Ghezzi in 1723 and shows Vivaldi's head and shoulders in profile. It exists in two versions: a first jotting kept at the Vatican Library, and a much lesser-known, slightly more detailed copy recently discovered in Moscow.[52] The oil painting, which can be seen in the International Museum and Library of Music of Bologna, is anonymous and is thought to depict Vivaldi due to its strong resemblance to the La Cave engraving.[53]

Style and influence

Vivaldi's music was innovative. He brightened the formal and rhythmic structure of the concerto, in which he looked for harmonic contrasts and innovative melodies and themes. Many of his compositions are flamboyantly exuberant.

Johann Sebastian Bach was deeply influenced by Vivaldi's concertos and arias (recalled in his St John Passion, St Matthew Passion, and cantatas). Bach transcribed six of Vivaldi's concerti for solo keyboard, three for organ, and one for four harpsichords, strings, and basso continuo (BWV 1065) based upon the concerto for four violins, two violas, cello, and basso continuo (RV 580).[7][54]

Posthumous reputation

During his lifetime, Vivaldi was popular in many countries throughout Europe, including France, but after his death his popularity dwindled. After the end of the Baroque period, Vivaldi's published concerti became relatively unknown, and were largely ignored. Even his most famous work, The Four Seasons, was unknown in its original edition during the Classical and Romantic periods.

In the early 20th century, Fritz Kreisler's Concerto in C, in the Style of Vivaldi (which he passed off as an original Vivaldi work) helped revive Vivaldi's reputation. This spurred the French scholar Marc Pincherle to begin an academic study of Vivaldi's oeuvre. Many Vivaldi manuscripts were rediscovered, which were acquired by the Turin National University Library as a result of the generous sponsorship of Turinese businessmen Roberto Foa and Filippo Giordano, in memory of their sons. This led to a renewed interest in Vivaldi by, among others, Mario Rinaldi, Alfredo Casella, Ezra Pound, Olga Rudge, Desmond Chute, Arturo Toscanini, Arnold Schering and Louis Kaufman, all of whom were instrumental in the revival of Vivaldi throughout the 20th century.

In 1926, in a monastery in Piedmont, researchers discovered fourteen folios of Vivaldi's work that were previously thought to have been lost during the Napoleonic Wars. Some missing volumes in the numbered set were discovered in the collections of the descendants of the Grand Duke Durazzo, who had acquired the monastery complex in the 18th century. The volumes contained 300 concertos, 19 operas and over 100 vocal-instrumental works.[55]

The resurrection of Vivaldi's unpublished works in the 20th century is mostly due to the efforts of Alfredo Casella, who in 1939 organized the historic Vivaldi Week, in which the rediscovered Gloria (RV 589) and l'Olimpiade were revived. Since World War II, Vivaldi's compositions have enjoyed wide success. Historically informed performances, often on "original instruments", have increased Vivaldi's fame still further.

Recent rediscoveries of works by Vivaldi include two psalm settings of Nisi Dominus (RV 803, in eight movements) and Dixit Dominus (RV 807, in eleven movements). These were identified in 2003 and 2005 respectively, by the Australian scholar Janice Stockigt. The Vivaldi scholar Michael Talbot described RV 807 as "arguably the best nonoperatic work from Vivaldi's pen to come to light since […] the 1920s".[56] Vivaldi's 1730 opera Argippo (RV 697), which had been considered lost, was rediscovered in 2006 by the harpsichordist and conductor Ondřej Macek, whose Hofmusici orchestra performed the work at Prague Castle on 3 May 2008—its first performance since 1730.

Works

A composition by Vivaldi is identified by RV number, which refers to its place in the "Ryom-Verzeichnis" or "Répertoire des oeuvres d'Antonio Vivaldi", a catalog created in the 20th century by the musicologist Peter Ryom.

Le quattro stagioni (The Four Seasons) of 1723 is his most famous work. Part of Il cimento dell'armonia e dell'inventione ("The Contest between Harmony and Invention"), it depicts moods and scenes from each of the four seasons. This work has been described as an outstanding instance of pre-19th century program music.[57]

Vivaldi wrote more than 500 other concertos. About 350 of these are for solo instrument and strings, of which 230 are for violin, the others being for bassoon, cello, oboe, flute, viola d'amore, recorder, lute, or mandolin. About forty concertos are for two instruments and strings, and about thirty are for three or more instruments and strings.

As well as about 46 operas, Vivaldi composed a large body of sacred choral music, such as the Magnificat RV 610. Other works include sinfonias, about 90 sonatas and chamber music.

Some sonatas for flute, published as Il Pastor Fido, have been erroneously attributed to Vivaldi, but were composed by Nicolas Chédeville.

Catalogues of Vivaldi works

Vivaldi's works attracted cataloging efforts befitting a major composer. Scholarly work intended to increase the accuracy and variety of Vivaldi performances also supported new discoveries which made old catalogs incomplete. Works still in circulation today may be numbered under several different systems (some earlier catalogs are mentioned here).

Because the simply consecutive Complete Edition (CE) numbers did not reflect the individual works (Opus numbers) into which compositions were grouped, numbers assigned by Antonio Fanna were often used in conjunction with CE numbers. Combined Complete Edition (CE)/Fanna numbering was especially common in the work of Italian groups driving the mid-20th century revival of Vivaldi, such as Gli Accademici di Milano under Piero Santi. For example, the Bassoon Concerto in B♭ major, "La Notte" RV 501, became CE 12, F. VIII,1

Despite the awkwardness of having to overlay Fanna numbers onto the Complete Edition number for meaningful grouping of Vivaldi's oeuvre, these numbers displaced the older Pincherle numbers as the (re-)discovery of more manuscripts had rendered older catalogs obsolete.

This cataloging work was led by the Istituto Italiano Antonio Vivaldi, where Gian Francesco Malipiero was both the director and the editor of the published scores (Edizioni G. Ricordi). His work built on that of Antonio Fanna, a Venetian businessman and the Institute's founder, and thus formed a bridge to the scholarly catalog dominant today.

Compositions by Vivaldi are identified today by RV number, the number assigned by Danish musicologist Peter Ryom in works published mostly in the 1970s, such as the "Ryom-Verzeichnis" or "Répertoire des oeuvres d'Antonio Vivaldi". Like the Complete Edition before it, the RV does not typically assign its single, consecutive numbers to "adjacent" works that occupy one of the composer's single opus numbers. Its goal as a modern catalog is to index the manuscripts and sources that establish the existence and nature of all known works.[lower-alpha 1]

In popular culture

The movie Vivaldi, a Prince in Venice was completed in 2005 as an Italian-French co-production under the direction of Jean-Louis Guillermou.[58] In 2005, ABC Radio National commissioned a radio play about Vivaldi, which was written by Sean Riley. Entitled The Angel and the Red Priest, the play was later adapted for the stage and was performed at the Adelaide Festival of the Arts.[59]

References

Notes

- These several numbering systems are cross-referenced at classical.net.

References

- "An anonymous portrait in oils in the Museo Internazionale e Biblioteca della Musica di Bologna is generally believed to be of Vivaldi and may be linked to the Morellon La Cave engraving, which appears to be a modified mirror reflection of it." Michael Talbot, The Vivaldi Compendium (2011), p. 148.

- Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- Roach, Peter (2011). Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-15253-2.

- "Vivaldi, Antonio" (US) and "Vivaldi, Antonio". Oxford Dictionaries UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- "Vivaldi". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- Michael Talbot and the Editors of the Encyclopædia Britannica, Antonio Vivaldi at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Michael Talbot, "Vivaldi, Antonio", Grove Music Online (subscription required)

- Walter Kolneder, Antonio Vivaldi: Documents of his life and works (Amsterdam: Heinrichshofen's Verlag, Wilhelmshaven, Locarno, 1982), 46.

- Michael Talbot, Vivaldi (London: J.M. Dent & Sons, Ltd., 1978), 39.

- Landon, p. 15

- Michael Talbot, Vivaldi (London: J.M. Dent & Sons, Ltd, 1978), 37.

- Heller, p. 41

- Michael Talbot, Vivaldi (London: J.M. Dent & Sons, Ltd., 1978), 36.

- Heller, p. 40

- Landon, p. 16

- Marc Pincherle, Vivaldi: Genius of the Baroque (Paris: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1957), 16

- Karl Heller, Antonio Vivaldi: The Red Priest of Venice, translated by David Marinelli (AMADEUS PRESS, 1991)

- Kolneder 1970, 29.

- Landon, p. 49

- Heller, p. 51

- Marc Pincherle, Vivaldi: Genius of the Baroque (Paris: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1957), 18.

- Heller, p. 77

- Heller, p. 78

- Landon, p. 26

- Marc Pincherle, Vivaldi: Genius of the Baroque (Paris: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1957), 24.

- Michael Talbot, Vivaldi (London: J.M. Dent & Sons, Ltd, 1978), 48.

- Heller, p. 54.

- Michael Talbot, Vivaldi (London: J.M. Dent & Sons, Ltd, 1978), 59.

- Marc Pincherle, Vivaldi: Genius of the Baroque (Paris: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1957), 38.

- Landon, p. 31

- Landon, p. 42

- Michael Talbot, Vivaldi (London: J.M. Dent & Sons, Ltd, 1978), 54.

- Michael Talbot, Vivaldi (London: J.M. Dent & Sons, Ltd, 1978), 58.

- Michael Talbot, Vivaldi (London: J.M. Dent & Sons, Ltd, 1978), 71.

- "Vivaldi's Venice", baroquemusic.org. "As far as his theatrical activities were concerned, the end of 1716 was a high point for Vivaldi. In November, he managed to have the Ospedale della Pietà perform his first great oratorio, Juditha Triumphans devicta Holofernis barbaric. [sic] This work was an allegorical description of the victory of the Venetians over the Turks in August 1716."

- Heller, p. 98

- Landon, p. 52

- Heller, p. 97

- Heller, p. 114

- Michael Talbot, Vivaldi (London: J.M. Dent & Sons, Ltd, 1978), 64.

- Michael Talbot, Vivaldi (London: J. M. Dent & Sons, Ltd, 1978), 66.

- Michael Talbot, Vivaldi (London: J.M. Dent & Sons, Ltd, 1978), 67.

- Vivaldi's connections with musical life in Prague and his association with Antonio Denzio, the impresario of the Sporck theater in Prague are detailed in Daniel E. Freeman, The Opera Theater of Count Franz Anton von Sporck in Prague (Stuyvesant, N.Y.: Pendragon Press, 1992).

- Walter Kolneder, Antonio Vivaldi: Documents of his life and works (Amsterdam: Heinrichshofen's Verlag, Wilhelmshaven, Locarno, 1982), 179.

- Walter Kolneder, Antonio Vivaldi: Documents of his life and works (Amsterdam: Heinrichshofen's Verlag, Wilhelmshaven, Locarno, 1982), 180.

- There are only three known surviving depictions of Vivaldi made in his lifetime: this caricature, a woodcut by la Cave, and an anonymous oil portrait of the composer and his violin. Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians has disputed the authenticity of the last portrait.

- Landon supplies this assertion and furthermore quotes the report of Vivaldi's death which reached Venice in the Commemorali Gradenigo: "Abbe Lord Antonio Vivaldi, incomparable virtuoso of the violin, known as the Red Priest, much esteemed for his compositions and concertos, who earned more than 50,000 ducats in his life, but his disorderly prodigality caused him to die a pauper in Vienna." Landon, p. 166

- Marc Pincherle, Vivaldi: Genius of the Baroque (Paris: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1957), 53.

- Talbot (p. 69) gives the 27th as the day of death. Formichetti (p. 194) reports that he died during the night and his death was the first registered on the next day. Heller (p. 263) states: "The composer's death is noted in the official coroner's report and in the burial account book of St. Stephen's Cathedral Parish as having occurred on 28 July 1741". But the so-called Totenbeschauprotokoll is not a reliable source, since the date can refer to when the entry was made, not to the actual time of death.

- Michael Lorenz, "Haydn Singing at Vivaldi's Exequies: An Ineradicable Myth" (Vienna 2014)

- Michael Talbot, The Vivaldi Compendium (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2011), 147–48.

- Michael Talbot, The Vivaldi Compendium (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2011), 87.

- Michael Talbot, The Vivaldi Compendium (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2011), 148.

- Wolff and Emery.

- Antonio Vivaldi biography by Alexander Kuznetsov and Louise Thomas, a booklet attached to the CD "The best of Vivaldi", published and recorded by Madacy Entertainment Group Inc, St. Laurent Quebec Canada

- Michael Talbot, liner notes to the CD Vivaldi: Dixit Dominus, Körnerscher Sing-Verein Dresden (Dresdner Instrumental-Concert), Peter Kopp, Deutsche Grammophon 2006, catalogue number 4776145

- Gerard Schwarz, Musically Speaking – The Great Works Collection: Vivaldi (CVP, Inc., 1995), 13.

- Antonio Vivaldi, un prince à Venise at IMDb

- "Angel and the Red Priest by Sean Riley". Airplay. Australian Broadcasting Corporation Radio National. 15 June 2011. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

Sources and further reading

- Brizi, Bruno, "Maria Grazia Pensa" in Music & Letters, Vol. 65, No. 1 (January 1984), pp. 62–64

- Bukofzer, Manfred (1947). Music in the Baroque Era. New York, W. W. Norton & Co. ISBN 0-393-09745-5.

- Cross, Eric (1984). Review of I libretti vivaldiani: recensione e collazione dei testimoni a stampa by Anna Laura Bellina;

- Formichetti, Gianfranco Venezia e il prete col violino. Vita di Antonio Vivaldi, Bompiani (2006), ISBN 88-452-5640-5.

- Heller, Karl Antonio Vivaldi: The Red Priest of Venice, Amadeus Press (1997), ISBN 1-57467-015-8

- Kolneder, Walter Antonio Vivaldi: Documents of His Life and Works, C F Peters Corp (1983), ISBN 3-7959-0338-6

- Robbins Landon, H. C., Vivaldi: Voice of the Baroque, University of Chicago Press, 1996 ISBN 0-226-46842-9

- Romijn, André. Hidden Harmonies: The Secret Life of Antonio Vivaldi, 2007 ISBN 978-0-9554100-1-7

- Selfridge-Field, Eleanor (1994). Venetian Instrumental Music, from Gabrieli to Vivaldi. New York, Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-28151-5.

- Talbot, Michael (1992). Vivaldi, second edition. London: J. M. Dent. American reprint, New York: Schirmer Books: Maxwell Macmillan International, 1993.

- Talbot, Michael, Antonio Vivaldi, Insel Verlag (1998), ISBN 3-458-33917-5 (in German)

- Talbot, Michael: "Antonio Vivaldi", Grove Music Online, ed. L. Macy (Accessed 26 August 2006) (subscription required)

- Wolff, Christoph, and Walter Emery. "Bach, Johann Sebastian". The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell. London: Macmillan Publishers, 2001.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Antonio Vivaldi |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Antonio Vivaldi. |

Works written by or about Antonio Vivaldi at Wikisource

Works written by or about Antonio Vivaldi at Wikisource- Antonio Vivaldi at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Catalog of instrumental works

- Complete works catalog

- Free scores by Antonio Vivaldi at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Free scores by Antonio Vivaldi in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- "Discovering Vivaldi". BBC Radio 3.

- The Mutopia Project has compositions by Antonio Vivaldi

- Project Anima Veneziana, Free English eBooks: 1. Talbot, M. Vivaldi. 1993; 2. Heller, K. Antonio Vivaldi: The Red Priest of Venice. 1997; 3. Pincherle, Marc. Vivaldi: Genius of the Baroque, 1957; 4. Ryom, Peter. Vivaldi Werkverzeichnis. 1st edition, 2007

- Works by or about Antonio Vivaldi at Internet Archive

- Works by Antonio Vivaldi at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Antonio Vivaldi at IMDb