Aquademics

Aquademics was a Michigan nonprofit organization established in 1990 to increase the number and presence of African American children in competitive water sports. In addition to sponsoring a competitive swimming team, Aquademics operated an academic support program. Based in Ann Arbor, Aquademics programs were open to all youth of color children, ages seven to sixteen, living in Washtenaw County.[1] In operation throughout the 1990s, Aquademics formally disbanded at the turn of the 21st century.

| |

| Motto | Swimmers Make Better Learners |

|---|---|

| Founded | 1990 |

| Type | Non-profit |

| Focus | Increasing the number of African American children in competitive water sports and encouraging their academic achievement |

The Aquademics model resembled other athletics programs created in the late 1980s and 1990s, whose goal was to increase youth of color participation in sports lacking in diversity and with a history of racial exclusion.[2] The Aquademics program was also guided by the precedent that sporting excellence is a means to teach children other forms of excellence, most importantly, academic excellence.[3]

The Aquademics model's impact can be measured by the number of former members currently in professions where credentials and opportunities require associate and college degrees. Aquademics alums are represented in the following professions: business, communications, nonprofit administration, computer science, law, and the military, including the U.S. Marine Corps and the U.S. Navy.[4]

Moreover, a few Aquademics alums and former staff have volunteered or are working in water sport professions.[5] Two head coaches, who started their water sport coaching with Aquademics, continued with their coaching careers. Aquademics' original coach, Vicki Hames-Frazier was a water sports instructor of children with special needs for the Washtenaw Intermediate School District. After Aquademics, Hames-Frazier became head coach of the co-ed swimming team at Ann Arbor Greenhills School. She is one of the first African American women to coach a high school competitive swimming team in Michigan.

Kelton Graham was Aquademics' longest-serving coach. Graham was a student athlete on the men's swimming team at Eastern Michigan University. After Aquademics, Graham took head coaching positions at both the club and high school levels. In 2006, he was appointed head coach of the Huron High School (Ann Arbor, Michigan) boys' swimming team.[6] In 2008, Graham led the boys' swimming team to its first Class A championship in 19 years. That same year, Graham was named the Michigan Interscholastic Swim Coaches Association Coach of the Year, becoming the first African American to receive this award.[7]

Beginnings

In 1990, Jeanine DeLay, faculty member and first coach of the Ann Arbor Greenhills School co-ed swimming team, met with former colleague, Wilma Allen, then Assistant Director, Research Services at CPHA, a national health information services firm. DeLay was interested in starting a swimming program for underserved kids whose access to swimming had been impeded by discrimination, inadequate resources and lack of coaching mentors.[8] Cognizant and supportive of appeals for educational reform in athletics voiced at the time by tennis champion, humanitarian and activist Arthur Ashe, Allen and DeLay, also committed the endeavor to a strong academic program.[9] They were joined in forming Aquademics by three other educators and health care professionals to comprise the founding board: Carmel Borders, adjunct faculty member in health education at Eastern Michigan University, Melvin Rhoden, Admissions Director of Ann Arbor Greenhills School and health company executive, Gloria Jackson.

Aquademics' name merged its two vital goals: Aqua(tics) and (aca)Demics. The motto served its mission: Swimmers Make Better Learners. The logo featured its goal: a Black swimmer smoothly churning through large waves.

The Southeastern Michigan Competitive Swimming Culture and Community

Southeastern Michigan is a long-established training site for competitive swimmers and well- recognized in the competitive swimming world. It boasts top-ranked, championship and highly respected college teams, among them the University of Michigan, Oakland University and Eastern Michigan University.[10]

Likewise, club programs, such as the Ann Arbor Swim Club and Club Wolverine include on their annual rosters several regionally and nationally ranked swimmers. School programs, such as the Ann Arbor Pioneer High School boys' and girls' swimming and diving teams, have won over thirty state championships since 1977.

Several southeastern Michigan water sport coaches are highly regarded, and swimmers come from across the nation and around the world to train and compete on the region's college teams.[11]

Aquademics depended on the good will and generous support of this talent and resource-rich, experienced and close-knit swimming culture and community.

Learning from History

Equally important, Aquademics learned from the enterprise of pioneers in African American swimming history who had established swimming programs in Detroit.

Knowledge about African Americans and their place in swimming history has been burdened by racism and obstructed by persistent and inaccurate stereotypes.[12] Water sports in America and the architecture of both private and public swimming pools represented a landscape set up for racial inequality and segregation. During the New Deal in the 1930s, the construction of public pools expanded reasons and some opportunities for all ethnic and racial groups to learn how to swim. Nevertheless, Blacks were prohibited from "Whites only" facilities.[13]

As a result, several communities with large numbers of African American citizens supported their own water sport recreation centers. One of the most visible in southeastern Michigan was the Lucy Thurman YWCA. The accomplishments of those who participated in the Lucy Thurman YWCA swimming programs in the first half of the 20th century are especially noteworthy.[14]

By the 1990s, when Aquademics swimmers jumped into the pool, the most pernicious structures of discrimination faced by Blacks in water sports had been dismantled. Evidence of these changes was affirmed by the fast times clocked by an upcoming generation of accomplished African American swimmers, trained under the farsighted leadership of Jim Ellis, head coach of the Philadelphia Department of Recreation, known in swimming circles as PDR.[15] Further, a number of metropolitan swim teams with a majority of African American swimmers were expanding their reach into urban communities and sending their record-breaking and qualifying time swimmers to state, national and international events. Among them were teams from Atlanta, Detroit, Baltimore, St. Louis, Washington, DC.[16]

Aquademics in the Water

The Ann Arbor YMCA was Aquademics' first pool. The founding team included four girls and two boys ranging in age from nine to fourteen. When the Aquademics team became too big for one lane instruction, the team obtained practice time at the Eastern Michigan University (EMU) pool, through the good offices of the EMU women's swimming coach. This was a temporary solution however, given the demands and expenses of training at a university facility. By 1993, Aquademics moved into its "home" pool at Clague Middle School.

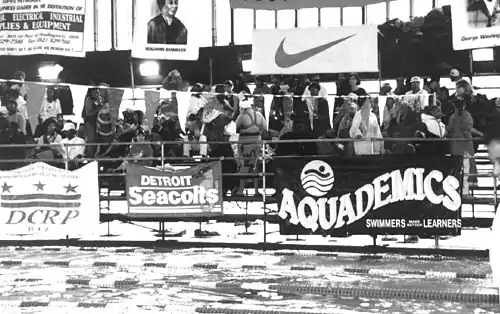

The Aquademics team decided on team colors of black and gold. After the group purchased its first practice fins, swimming lessons, training and competitions with other local clubs followed. By 1993, the 'Aquademicsmobile,' a donated van, took Aquademics swimmers all over southeastern Michigan, accompanied by a caravan of family and friend supporters. Rival teams included: University Liggett School, Ypsilanti Otters, Detroit Northside Seacolts and the Detroit Recreational Center. Aquademics was honored with the 1994 Award for its service to community youth by the Friends of the C.O.P.E. O'Brien Center for Youth Development, a group offering a wide range of treatment and counselling services to young people in Washtenaw County.[17]

A few months before receiving this award, in February 1994, the Aquademics team and families travelled to and competed in the Black History Invitational, then in its eighth year. The BHI, hosted by the Washington DC Department of Parks and Recreation, is the premier gathering of competitive African American swimmers in the nation.[18] The Aquademics team participated in five Black History Invitationals.[19] In 1999, inspired by the success of the BHI, Aquademics hosted a smaller competition, the Kwanzaa Invitational. It was held from December 17–19, 1999 at the University of Michigan Canham Natatorium, and included teams from around the region.[20]

Swimmers Make Better Learners

Scholastic achievement was central to Aquademics. To fulfill its mission, three initiatives were supported:

- The program established an annual camp. The Aquademics Camp was at once a water sport clinic, a cultural experience and a summer school. In addition to the swimming practices and training common to all sport camps, the fundamental skills of other water sports, such as water polo, water skiing and scuba diving were introduced. Campers took field trips to several African American history and cultural institutions: the Charles Wright Museum of African American History, the Black Madonna Bookstore, and the African art collections at the Detroit Institute of Art. In 1993, campers met with several Lucy Thurman YWCA alumna, who provided a cultural history lesson about their experiences as synchronized swimmers in the 1930s and 1940s. Finally, the camp incorporated study skill and time management instruction, learning style discussions and offered tutorials in specific subjects.

- A college scholarship fund was launched to provide financial assistance to Aquademics members with stellar academic records during high school. Funded by former health care researcher Linda Sprankle, an advocate of programs committed to youth of color, the Sprankle Scholarship became synonymous with high academic achievement, and for Aquademics members, an honor as competitive and prestigious as getting medals in swimming.

- The group engaged Betty Springfield, a volunteer program director, to sustain an effective academic program. She joined the founding board to lend expertise for two ends: to strengthen the academic support and counselling programs; and to shift the program toward family-centered leadership.

In 1995, Springfield increased and expanded the academic counselling staff, instituted after-practice tutorials and secured a flexible partnership with another academic group associated with the Ann Arbor Public Schools, The African American Academy.[21]

Then in 1996, the founding Board approved a plan to transfer governing authority to parents and families of Aquademics members. To the 'Swimmers Make Better Learners' motto, another watchword was embraced: "Always Remember that the Children Are in the Water."

This expression called to mind the power of water and charged everyone affiliated with Aquademics to advance the promise and well-being of children and to promote life skills that keep children out of harm's way.

Family-Centered Leadership

The transfer to a family-centered board in 1997 meant that the founders and nurturers of the organization turned governance over to the sustainers and legacy-builders of Aquademics. The shift had the immediate effect of increasing the number of children belonging to the program. Over the next two years, the group concentrated on educating area youth groups and on increasing awareness of Aquademics' mission to community leaders. In 1999, Aquademics was given a Community Recognition Award for 'Outstanding Service by an Organization' by the Trustees of Washtenaw Community College.[22]

Challenges

Aquademics was a grass-roots nonprofit organization. As a result, the group obtained resources through several approaches and maintained its programs by relying on a combination of grants, business sponsorships, fund-raisers, annual giving and in-kind donations. Critical seed grants were awarded by the Ann Arbor Area Community Foundation and the Southeastern Michigan Community Foundation.[23] Original corporate sponsors included two local banks. In-kind donations came from a range of sources, from swimming kickboards to donated coaching expertise. The programs, however, were not free. Each family contributed to the funding of camp and was assessed a participation fee every season.

Fund-raising was all-consuming and required major time commitments by families and volunteers who worked with Aquademics. Scaling up the program, to provide financial security and a stable source of income, proved increasingly difficult. With no endowment, the organization had to survive from season to season. Likewise, the advantage of being in an area with abundant swimming resources, also meant that Aquademics as a development or bridge program encountered some turnover to other clubs, whose goals did not require academics and cultural components.

Because of all of these challenges, the board of Aquademics determined to end operations at the beginning of the 21st century.

Legacy

The history of Aquademics is emblematic of the success and obstacles that confront individuals and groups whose purposes are to diversify the face of an exclusive sport and to transform a sport establishment that has been neither welcoming nor accessible to large numbers of people because of discrimination. Swimming may have more to answer for. Swimming pools and beaches for water sport recreation were symbols of segregation. They became contested sites during the civil rights movement in the 1960s. But at the same time, the wade-ins, and brave calls to "come on in and swim" encouraged and strengthened the African American swimming movement.[24]

Today, it is no longer as uncommon to see African Americans at the elite levels of swimming and other water sports. Over the last two decades, several elite African American swimmers have not only broken American records, but have displayed their willingness to be mentors to a new generation of Black swimmers.[25] Soon after Cullen Jones, an African American freestyler became the first African American to hold or share a world record in swimming at the Beijing Olympics in 2008, he described his hopes that he would work to increase the number of African American children in swimming.[26]

As a result of these promising changes, it might be said that programs like Aquademics are no longer important. Or that it is not surprising a program like Aquademics has disbanded, because it is no longer necessary. But lost and ignored knowledge about the heritage of African Americans in swimming and its importance as a life skill have taken a toll and create a perilous cultural undercurrent that continues to have fatal consequences. Alarmingly, over half of African Americans do not know how to swim today.[27] Their encounters with water are therefore more likely to be life-threatening. The tragic statistics reveal that they are: African American children, ages 10 to 14 drown at five times the rate of other ethnic and racial groups in the United States.

Fortunately, today, other organizations are advancing the legacy of Aquademics and programs similar to it. And simultaneously, they are rediscovering and reclaiming lost knowledge and heritage as well as documenting the reality that Black children always were, have been and always will be in the water.

References

- Schutte, Pat, "Kids mix swimming, social enrichment,"Ann Arbor News 1990

- Tennis Across America, National Junior Tennis League

- Arthur Ashe comments

- Communications with former Aquademics participants or family members

- Communications with former Aquademics family members

- "Club Wolverine".

- McCabe, Mick, "Standing Alone," Detroit Free Press, February 29, 2008, 10C

- Inadequate resources

- Top-ranked teams

- For the Ann Arbor Pioneer Boys' Swimming & Diving Championship Results: http://www.mhsaa.com/Sports/BoysSwimmingandDiving/TeamChampions.aspx For the Ann Arbor Pioneer Girls' Swimming & Diving Championship Results: http://www.mhsaa.com/Sports/GirlsSwimmingDiving/TeamChampions.aspx

- Hoose, Phillip M., Necessities: Racial Barriers in American Sports, Chapter 4, Random House, Inc., 1989.

- Wiltse, Jeff, Contested Waters: A Social History of Swimming Pools in America, The University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

- Thurman Alums

- Hoose, Phillip M., "A New Pool of Talent," New York Times Magazine, April 29, 1990, p.49

- Mullen, P.H., "The New Wave," Swimming World and Junior Swimmer, April, 1993, pp.30-35.

- Romaker, Robert L., "Wonder in the Water," Ann Arbor News June 1994

- http://dpr.dc.gov/dpr/cwp/view,a,1239,q,638886.asp

- BHI participation

- Kwanzaa Invitational, Ann Arbor News

- Ann Arbor Academy

- Washtenaw County Award

- Treml, William B., "Aquademics immerses students in learning," Ann Arbor News

- Pitts, Lee, "Black Splash: The History of African-American Swimmers,"

- Cullen Jones

- Zinser, Lynn (2006-06-19). "Everyone into the Water". The New York Times.

- "CDC - National Center for Injury Prevention and Control Redirect Page".

- minority swimming.com