Arbeitslager

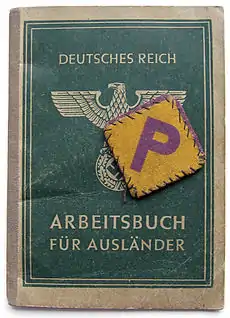

Arbeitslager (German pronunciation: [ˈʔaʁbaɪtsˌlaːɡɐ]) is a German language word which means labor camp. Under Nazism, the German government (and its private-sector, Axis, and collaborator partners) used forced labor extensively, starting in the 1930s but most especially during World War II. Another term was Zwangsarbeitslager ("forced labor camp").

The Nazis operated several categories of Arbeitslager for different categories of inmates. The largest number of them held civilians forcibly abducted in the occupied countries (see Łapanka for Polish context) to provide labour in the German war industry, repair bombed railroads and bridges, or work on farms and in stone quarries.[1]

The Nazis also operated concentration camps, some of which provided free forced labor for industrial and other jobs while others existed purely for the extermination of their inmates. A notable example is Mittelbau-Dora labor camp complex that serviced the production of the V-2 rocket. See List of German concentration camps for more. The large chemical works at Monowitz and owned by IG Farben was near Auschwitz and was designed to produce synthetic rubber and fuel oil. The labour needed for its construction was supplied by several labour camps around the works. Some of the prisoners were Auschwitz inmates, who were selected for their technical skills, such as Primo Levi for example.

Arbeitskommandos

Arbeitskommandos, officially called Kriegsgefangenenarbeitskommando were sub-camps under Prisoner-of-war camps for holding prisoners of war of lower ranks (below sergeant), who were working in industries and on farms. This was permitted under the Third Geneva Convention provided they were accorded proper treatment. They were not allowed to work in industries manufacturing war materials, but this restriction was frequently ignored by the Germans. They were always under the administration of the parent prisoner-of-war camp, which maintained records, distributed International Red Cross packages and provided at least minimal medical care in the event of the prisoner's sickness or injury. The number of prisoners in an Arbeitskommando was usually between 100 and 300.

One should differentiate these from sub-camps of Nazi concentration camps operated by the SS, which were also called Arbeitskommando. Because of the two different types there is some confusion in the literature, with the result of occasional reports of prisoners-of-war being held in concentration camps. In some cases the two types were physically adjacent, when both POWs and KL-inmates were working at a large facility such as a coal mine or chemical plant.[2] They were always kept apart from each other.

See also

References

- "Świadkowie: Jacek Kisielewski". Zapomniane obozy nazistowskie. Dom Spotkań z Historią DSH. Archived from the original on 5 December 2013. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- British POW and Auschwitz prisoners working at IG Farben plant