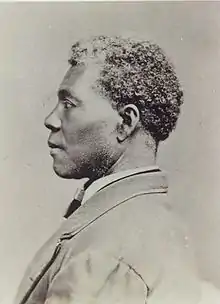

Archer Alexander

Archer Alexander (c. 1810 or 1815 – December 8, 1879)[2] was a formerly enslaved person who served as the model for the emancipated slave in the Emancipation Memorial (1876) located in Lincoln Park in Washington, D.C.[3] He was the subject of an 1885 biography, The Story of Archer Alexander, written by William Greenleaf Eliot.[3]

| Archer Alexander | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | circa 1810 Richmond |

| Died | December 8, 1879 St. Louis |

| Occupation | Model |

| Relatives | Muhammad Ali (great-great-great grandson)[1] Rahman Ali (great-great-great grandson) Laila Ali (great-great-great-great granddaughter) |

Early years

Alexander was born near Richmond, Virginia, about 1810, as slave.[3] According to Eliot, he was born in approximately 1815 on the plantation of the Ferrell family in Fincastle, Virginia.[4] Archer's father was sold by Ferrell to pay off debts while Archer was still a child, but shortly thereafter, Delaney died and left Archer Alexander to his son, Tom Ferrell, who moved to Missouri, in 1831,[3] taking his slave with him.[4] Alexander's mother, left behind in Virginia, died only a few months later. Alexander himself was hired out by Ferrell to local brickyards in St. Louis, until he needed even more money, when he sold Alexander to a farmer named Richard H. Pitman who lived on the border of St. Charles County and Warren County.

Archer Alexander had married an enslaved woman named Louisa, who was owned by James Naylor, and she accompanied him. Alexander was purchased in 1844 and worked for Hickman for more than twenty years. He was sufficiently respected by Naylor that he was given the responsibility of functioning in an overseer capacity on the farm. During this time, Archer and Louisa Alexander became the parents of several children, some of whom Naylor sent away because of their behavior.

American Civil War

Before the onset of the American Civil War, Alexander listened to the political discussion and determined that he would flee from his life in slavery if the opportunity arose. In 1861, Alexander covertly notified a group of Union troops that a bridge they intended to use had been sabotaged by Confederate sympathizers.[3] He was shortly thereafter suspected of being the source of this information and had to flee the farm. He was captured by slave catchers, but he broke free and returned to St. Louis, where he obtained employment under protection of the Federal provost-marshal.[3]

He went downtown to look for work in one of the public markets. Eliot's wife was there as well, having come to hire a servant. She hired Alexander, and brought him home. Alexander proved to be reticent about his recent history, leading Eliot himself to suspect that Alexander was an escaped slave, which left him in an uncomfortable situation. He had some years earlier stated that he personally would never return a fugitive slave to his former master, and he now faced that very situation. He obtained a certificate to keep Alexander for thirty days, and quickly wrote Hickman, offering to buy Alexander from him. Hickman turned down the offer, vowing he would have the slave back.

Two days before the expiration of his certificate, Alexander was found by some slave catchers Hickman had evidently hired. Eliot managed to find Alexander and keep him safe until the Emancipation Proclamation was issued. Alexander and his wife were reunited, if only for a short time. In 1866, Louisa decided to return to Naylor's house for some things she had left there. Alexander would later find out that Louisa had died, two days after her arrival, of an unidentified disease.

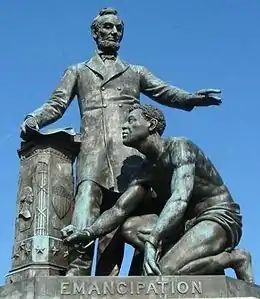

Emancipation Memorial

In 1869, Eliot was working with a group to build a statue of Lincoln. The funding for an Emancipation Memorial, featuring a statue of Lincoln, had begun with a $5 donation from a former slave, Charlotte Scott, from Virginia. All of the initial funds raised were from donations from former slaves, later matched by donations from The Western Sanitary Commission, a St. Louis-based volunteer war-relief agency.[5] Thomas Ball had an acceptable model made, but Eliot's group wanted to have a real freedman pose for it. Eliot gave Ball a photo of Alexander, and he was chosen as the model.

In 1876, the statue was unveiled, with a number of notable people in attendance, including President Ulysses S. Grant, members of his cabinet, Supreme Court justices, other government figures, and Frederick Douglass, another former slave. However, neither Alexander nor Eliot was present.

Death

He died in St. Louis, Missouri, on December 8, 1879.[3] Eliot and his son, Christopher, were with his friend Alexander, and Archer gave Christopher a gold watch for teaching him how to read. Eliot noted that Alexander died thanking God that he had died in freedom.

According to DNA research, Muhammad Ali's paternal grandmother was Alexander's great-granddaughter.[6]

Farther reading

- Alexander, Errol D. "Rattling of the Chains", a descendant and researcher-biographer of Archer Alexander.

- Christensen, Lawrence O. Dictionary of Missouri Biography. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8262-1222-0

References

Citations

- Strauss 2018

- Griffith 2011

- Johnson 1906, p. 74

- Eliot 1885, pp. 17–27

- nps.gov, doc. 87

- Strauss 2018

Sources

- Eliot, William Greenleaf (1885). The Story of Archer Alexander: From Slavery to Freedom, March 30, 1863. Boston, Mass.: Cupples, Upham and Company: Old Corner Bookstore. Retrieved November 15, 2020 – via Documenting the American South (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill).

- Griffith, Susan J. (2011). "Alexander, Archer (ca. 1810–1879)". The Online Encyclopedia of Significant People and Places in African American History. Retrieved October 5, 2013 – via BlackPast.org.

- Johnson, Rossiter, ed. (1906). "Alexander, Archer". The Biographical Dictionary of America. 1. Boston, Mass.: American Biographical Society. p. 74. Retrieved November 15, 2020 – via en.wikisource.org.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Strauss, Ben (October 2, 2018). "DNA evidence links Muhammad Ali to heroic slave, family says". Washington Post.