Armenian Genocide

The Armenian Genocide[lower-alpha 1] was the systematic mass murder and ethnic cleansing of ethnic Armenians from Anatolia and adjoining regions by the Ottoman government during World War I.

| Armenian Genocide | |

|---|---|

| Part of World War I | |

Bodil Biørn's caption: "The Armenian leader Papasian considers the last remnants of the horrific murders at Deir ez-Zor in 1915–1916." | |

| Location | Ottoman Empire |

| Date | 1915–Disputed |

| Target | Ottoman Armenians |

Attack type | Genocide, ethnic cleansing, expulsion, death march |

| Deaths | Estimated around 1 million |

| Perpetrators | Young Turks Movement, Committee of Union and Progress |

| Trials | Ottoman Special Military Tribunal |

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Armenia |

Coat of Arms of Armenia |

| Timeline |

During its invasion of Russian and Persian territory, Ottoman paramilitaries massacred local Armenians; massacres turned into genocide following the catastrophic defeat in the Battle of Sarikamish (January 1915), which was blamed on Armenian treachery. In the minds of the Ottoman leaders, isolated indications of Armenian resistance were taken as evidence of a general insurrection. Armenian soldiers in the Ottoman Army were disarmed pursuant to a February order and later killed.

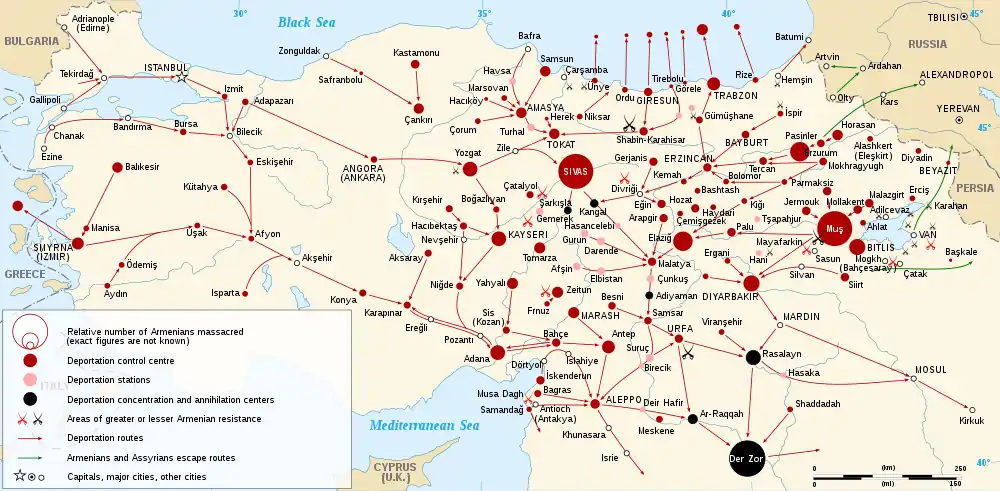

The start of the genocide is conventionally held to be 24 April 1915, the day that Ottoman authorities rounded up, arrested, and deported hundreds of Armenian intellectuals and community leaders from Constantinople (now Istanbul). According to the Tehcir Law, an estimated 800,000 to 1.2 million women, children, elderly, and infirm Armenians were deported on death marches leading to the Syrian Desert in 1915 and 1916. Driven forward by paramilitary escorts, the deportees were deprived of food and water and subjected to periodic robbery, rape, and massacre. Only around 200,000 deportees were still alive by the end of 1916; another 100,000 to 200,000 Armenian women and children were forcibly integrated into Muslim households. According to some definitions the genocide includes the Republic of Turkey's massacres of tens of thousands of Armenian civilians during the 1920 Turkish–Armenian War. During this time period, Assyrians and Greeks were also targeted for extermination.

In contrast to the vast majority of historians, Turkey denies that any crime was committed against the Armenian people. As of 2019, 32 countries, including the United States, Russia, and Germany, have recognized the events as a genocide.

Terminology

English-language words and phrases used by contemporary accounts to characterize the event include "massacres", "atrocities", "annihilation", "holocaust", "the murder of a nation", "race extermination" and "a crime against humanity".[1] In German, the word Völkermord (lit. 'the murder of a people')—directly equivalent to the later English word genocide—was frequently used for killing of Armenians, beginning with the Hamidian massacres in the 1890s.[2] Polish-Jewish lawyer Raphael Lemkin coined the word genocide in 1943, with the fate of the Armenians in mind; he later explained that: "it happened so many times ... first to the Armenians, then after the Armenians, Hitler took action."[3] Although most legal experts agree that the 1948 Genocide Convention does not have retroactive application,[4] the Armenian Genocide otherwise meets the legal definition.[5][6][7]

The survivors of the genocide used a number of Armenian terms to name the event, most commonly Medz Yeghern (Great Crime), but encompassing a variety of terms including chart ("massacre") and Aghed or Aghet (Աղետ), usually translated as "Catastrophe".[8][9][10] The Turkish government uses expressions such as "so-called Armenian genocide", "Armenian Question", or "Armenian Tragedy", often characterizing the charge of genocide as "Armenian allegations"[11] or "Armenian lies".[12]

Background

Armenians under Ottoman rule

The presence of Armenians in Anatolia is documented since the sixth century BCE, almost a millennium prior to the Turkic migrations.[13][14] The western portion of historical Armenia had come under Ottoman jurisdiction by the Peace of Amasya (1555) and was permanently divided from Eastern Armenia by the Treaty of Zuhab (1639).[15][16] The vast majority of Armenians were grouped together into a semi-autonomous community, the Armenian millet, which was led by one of the spiritual heads of the Armenian Apostolic Church, the Armenian Patriarch of Constantinople. Under the millet system, the Armenian community was allowed to rule itself under its own system of governance with fairly little interference from the Ottoman government. Most Armenians—approximately 70%—lived in poor and dangerous conditions in the rural countryside. The wealthy, Constantinople-based Amira class comprised a social elite whose members included the Duzians (Directors of the Imperial Mint), the Balyans (Chief Imperial Architects) and the Dadians (Superintendent of the Gunpowder Mills and manager of industrial factories).[17][18]

In the eastern provinces, the Armenians were subject to the whims of their Turkish and Kurdish neighbors, who would regularly overtax them, subject them to brigandage and kidnapping, force them to convert to Islam, and otherwise exploit them without interference from central or local authorities.[18] In accordance with the Islamic dhimmi system, non-Muslims' rights to property, livelihood and freedom of worship were protected, but they were in essence treated as second-class citizens in the empire and referred to in Turkish as gavours, a pejorative word meaning "infidel" or "unbeliever". The clause of the Pact of Umar which prohibited non-Muslims from building new places of worship was historically imposed on some communities of the Ottoman Empire and ignored in other cases, at the discretion of local authorities. Although there were no laws mandating religious ghettos, this led to non-Muslim communities being clustered around existing houses of worship.[19][20] Testimony against Muslims by Christians and Jews was inadmissible in courts of law wherein a Muslim could be punished; this meant that their testimony could only be considered in commercial cases. They were forbidden to carry weapons or ride atop horses and camels.[19][21]

Reform, 1840s–1880s

In the mid-19th century, the three major European powers—the United Kingdom, France and Russia—began to criticize the Ottoman Empire's treatment of its Christian minorities and pressure it to grant equal rights to all its subjects. From 1839 to the declaration of a constitution in 1876, the Ottoman government instituted the Tanzimat, a series of reforms designed to improve the status of minorities. Nevertheless, most of the reforms were never implemented because the empire's Muslim population rejected the principle of equality for Christians. By the late 1870s, the European Greeks, along with several other Christian nations in the Balkans, frustrated with their conditions, had, often with the help of the Entente powers, broken free of Ottoman rule.[22]:192[23] The Armenians remained, by and large, passive during these years, earning them the title of "loyal millet".[24]

In the mid-1860s and early 1870s this passivity gave way to new currents of thinking in Armenian society. Led by intellectuals educated at European universities or American missionary schools, Armenians began to question their second-class status and press for better treatment from their government.[21]:36 Following the violent suppression of Christians during the Great Eastern Crisis, particularly in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria and Serbia, the United Kingdom and France invoked the 1856 Treaty of Paris by claiming that it gave them the right to intervene and protect the Ottoman Empire's Christian minorities.[21]:35ff Under growing pressure, the government of Sultan Abdul Hamid II declared itself a constitutional monarchy with a parliament (which was almost immediately prorogued) and entered into negotiations with the powers. At the same time, the Armenian patriarch of Constantinople, Nerses II, forwarded Armenian complaints of widespread "forced land seizure ... forced conversion of women and children, arson, protection extortion, rape, and murder" to the Powers.[21]:37

The Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878 ended with Russia's decisive victory and its army in occupation of large parts of eastern Turkey, but not before entire Armenian districts had been devastated by massacres carried out with the connivance of Ottoman authorities. In the wake of these events, Patriarch Nerses and his emissaries made repeated approaches to Russian leaders to urge the inclusion of a clause granting local self-government to the Armenians in the forthcoming Treaty of San Stefano, which was signed on 3 March 1878. The Russians were receptive and drew up the clause, but the Ottomans flatly rejected it during negotiations. In its place, the two sides agreed on a clause making the Sublime Porte's implementation of reforms in the Armenian provinces a condition of Russia's withdrawal, thus designating Russia the guarantor of the reforms.

Upon receiving a copy of the treaty, Britain promptly objected to it and particularly Article 16, which it saw as ceding too much influence to Russia. It immediately pushed for a congress of the great powers to be convened to discuss and revise the treaty, leading to the Congress of Berlin in June–July 1878.[lower-alpha 2] Britain and Russia, having already reached an understanding a month before the congress, entered with the other great powers into the drafting of a final treaty. The old clause was replaced with one in which the Sublime Porte agreed "to carry out, without further delay, the improvements and reforms demanded by local requirements in the provinces inhabited by Armenians", and to "guarantee their security against the Circassians and the Kurds."[21]:38–39 The clause was adopted as Article 61 of the Treaty of Berlin on the last day of the Congress, 13 July 1878, to the deep disappointment of the Armenian delegation.[21]:38–39

Armenian national liberation movement

Prospects for reforms faded rapidly following the signing of the Berlin treaty, as security conditions in the Armenian provinces went from bad to worse and abuses proliferated. Upset with this turn of events, a number of disillusioned Armenian intellectuals living in Europe and Russia decided to form political parties and societies dedicated to the betterment of their compatriots in the Ottoman Empire. In the last quarter of the 19th century, this movement came to be dominated by three parties: the Armenakan, whose influence was limited to Van; the Social Democrat Hunchakian Party; and the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (Dashnaktsutiun). Ideological differences aside, all the parties had the common goal of achieving better social conditions for the Armenians of the Ottoman Empire through self-defense[26][27] and advocating increased European pressure on the Ottoman government to implement the promised reforms.

Hamidian massacres, 1894–1896

Soon after the Treaty of Berlin was signed, Sultan Abdul Hamid II (1876–1909) attempted to forestall the implementation of its reform provisions by asserting that Armenians did not make up a majority in the provinces and that their reports of abuses were largely exaggerated or false. In 1890, Abdul Hamid created a paramilitary outfit known as the Hamidiye, which was mostly made up of Kurdish irregulars tasked to "deal with the Armenians as they wished".[20]:40 As Ottoman officials intentionally provoked rebellions (often as a result of over-taxation) in Armenian populated towns, such as in Sasun in 1894 and Zeitun in 1895–1896, those regiments were increasingly used to deal with the Armenians by way of oppression and massacre. In some instances, Armenians successfully fought off the regiments and in 1895 brought the excesses to the attention of the Great Powers, who subsequently condemned the Porte.[21]:40–42

In May 1895, the Powers forced Abdul Hamid to sign a new reform package designed to curtail the powers of the Hamidiye, but, like the Berlin Treaty, it was never implemented. On 1 October 1895, 2,000 Armenians assembled in Constantinople to petition for the implementation of the reforms, but Ottoman police units violently broke the rally up.[20]:57–58 Soon, massacres of Armenians broke out in Constantinople and then engulfed the rest of the Armenian-populated provinces of Bitlis, Diyarbekir, Erzurum, Harput, Sivas, Trebizond (Trabzon), and Van. Estimates differ on how many Armenians were killed, but European documentation of the pogroms, which became known as the Hamidian massacres, placed the figures at between 100,000 and 300,000.[29]

Although Hamid was never directly implicated, it is believed that the massacres had his tacit approval.[21]:42 Frustrated with European indifference to the massacres, a group of members of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation seized the European-managed Ottoman Bank on 26 August 1896. This incident brought further sympathy for Armenians in Europe and was lauded by the European and American press, which vilified Hamid and painted him as the "great assassin", "bloody Sultan", and "Abdul the Damned".[20]:35, 115 The Great Powers vowed to take action and enforce new reforms, which never came to fruition due to conflicting political and economic interests.

Young Turk Revolution of 1908

On 24 July 1908, Armenians' hopes for equality in the Ottoman Empire brightened when a coup d'état staged by officers in the Ottoman Third Army based in Salonika removed Abdul Hamid II from power and restored the country to a constitutional monarchy. The officers were part of the Young Turk movement that wanted to reform administration of the perceived decadent state of the Ottoman Empire and modernize it to European standards.[30] The movement was an anti-Hamidian coalition made up of two distinct groups, the liberal constitutionalists and the nationalists. The former were more democratic and accepting of Armenians, whereas the latter were less tolerant of Armenians and their frequent requests for European assistance.[20]:140–41

One of the numerous factions within the Young Turk movement was a secret revolutionary organization called the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP). It drew its membership from disaffected army officers based in Salonika and was behind a wave of mutinies against the central government. In 1908, elements of the Third Army and the Second Army Corps declared their opposition to the Sultan and threatened to march on the capital to depose him. Abdulhamid, shaken by the wave of resentment, stepped down from power as Armenians, Greeks, Assyrians, Arabs, Bulgarians and Turks alike rejoiced in his dethronement.[20]:143–44

Adana massacre of 1909

Abdulhamid attempted a countercoup in early 1909, ultimately resulting in the 31 March Incident on 13 April 1909. Some reactionary Ottoman military elements, joined by Islamic theological students, aimed to return control of the country to the Sultan and the rule of Islamic law. Riots and fighting broke out between the reactionary forces and CUP forces, until the CUP was able to put down the uprising and court-martial the opposition leaders. While the movement initially targeted the Young Turk government, it spilled over into pogroms against Armenians who were perceived as having supported the restoration of the constitution.[21]:68–69 About 4,000 Turkish civilians and soldiers participated in the rampage.[31] Estimates of the number of Armenians killed in the course of the Adana massacre range between 15,000 and 30,000 people.[21]:69[32]

Conflict in the Balkans and Russia

In 1912, the First Balkan War broke out and ended with the defeat of the Ottoman Empire as well as the loss of 85% of its European territory.[21]:84 The Turkish nationalist movement in the country gradually came to view Anatolia as their last refuge. An important consequence of the Balkan Wars was also the mass expulsion of Muslims (known as muhacirs) from the Balkans. Beginning in the mid-19th century, hundreds of thousands of Muslims, including Turks, Circassians, and Chechens, were forcibly expelled and others voluntarily migrated from the Caucasus and the Balkans (Rumelia) as a result of the Russo-Turkish wars, the Russo-Circassian War and the conflicts in the Balkans. Muslim society in the empire was incensed by this flood of refugees. A journal published in Constantinople expressed the mood of the times: "Let this be a warning ... O Muslims, don't get comfortable! Do not let your blood cool before taking revenge".[21]:86 As many as 850,000 of these refugees were settled in areas where the Armenians resided. The muhacirs resented the status of their relatively well-off neighbors and, as historian Taner Akçam and others have noted, some of them came to play a pivotal role in the killings of the Armenians and the confiscation of their properties during the genocide.[21]:86–87

Decision and early actions

Entry into World War I

By 1914, Ottoman authorities had already begun a propaganda drive to present Armenians living in the Ottoman Empire as a threat to the empire's security who planned to launch uprisings against the government.[22]:220 In July 1914, the Ottoman government had sent representatives to the Armenian congress at Erzurum, demanding that Ottoman Armenians incite an insurrection of Russian Armenians against the Russian army in the event a Caucasus front was opened.[21]:136[33] Sporadic massacres of Armenians were ongoing from the late summer.[34]

On 2 November 1914, the Ottoman Empire opened the Middle Eastern theater of World War I by entering hostilities on the side of the Central Powers and against the Allies. The battles of the Caucasus Campaign, the Persian Campaign and the Gallipoli Campaign affected several populous Armenian centers.[21]:136[33] On 24 December 1914, Minister of War Enver Pasha implemented a plan to encircle and destroy the Russian Caucasus Army at Sarikamish in order to regain territories lost to Russia after the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878. Enver Pasha's forces were routed in the battle, and almost completely destroyed. Returning to Constantinople, Enver Pasha publicly blamed his defeat on Armenians in the region having actively sided with the Russians.[20]:200

In November 1914, the Shaykh ul-Islam, Ürgüplü Mustafa Hayri Efendi, proclaimed Jihad (Holy War) against the Christians: this was later used as a factor to provoke radical masses in the implementation of the Armenian Genocide.[35] The war was intended to lead to the Ottoman state becoming greater and more powerful than it had ever been; in the world envisioned by the Unionist leaders, Ottoman society was to become exclusively Turkish and Muslim; there was no place for the Christian Armenians in this society.[36]

Decision to commit genocide

Letter sent by Bahaeddin Şakir, 3 March 1915[38]

Talaat Pasha to a German diplomat, June 1915[39]

A few historians such as Vahakn Dadrian have argued that the genocide was planned in advance and that the war only provided an opportunity for it, but this viewpoint is a minority one.[40] Due to the lack of documentation, it is debated when and how the decision to murder the Armenians came about, although most historians date the final decision to the end of March or early April 1915. Based on the letter from Bahaeddin Şakir quoted at right, Akçam concludes that the decision was made between 15 February and 3 March 1915.[38]

According to Gerard Libaridian, the decision to enter the war and the decision to begin the genocide were part and parcel of the same process. The war held out the promise of national greatness once the Allies were defeated, while the Armenians were seen as an inner enemy holding the Turks back from the national glory that was the dream of the Unionist Central Committee.[41] Furthermore, the war-time radicalising atmosphere of emergency and national crisis made it possible to pursue policies that would be seen as unacceptable in peace-time.[41]

"Special Organization"

In 1913, the Committee of Union and Progress founded the "Special Organization" (Turkish: Teşkilât-ı Mahsusa).[42][20]:182, 185 Later in 1914, the Ottoman government influenced the direction the Special Organization was to take by releasing criminals from central prisons to be the central elements of this newly formed Special Organization.[43] According to the Mazhar commissions attached to the tribunal as soon as November 1914, 124 criminals were released from Bünyan prison.[44] Little by little from the end of 1914 to the beginning of 1915, hundreds, then thousands of prisoners were freed to form the members of this organization. Later, they were charged with escorting the convoys of Armenian deportees.[45]

Labour battalions

On 25 February 1915, the Ottoman General Staff released the War Minister Enver Pasha's Directive 8682 on "Increased security and precautions" to all military units calling for the removal of all ethnic Armenians serving in the Ottoman forces from their posts and for their demobilization. They were assigned to the unarmed Labour battalions (Turkish: amele taburları). The directive accused the Armenian Patriarchate of releasing State secrets to the Russians. Enver Pasha explained this decision as "out of fear that they would collaborate with the Russians".[46] Traditionally, the Ottoman Army only drafted non-Muslim males between the ages of 20 and 45 into the regular army. The younger (15–20) and older (45–60) non-Muslim soldiers had always been used as logistical support through the labour battalions. Before February, some of the Armenian recruits were utilized as labourers (hamals), though they would ultimately be executed.[47] Transferring Armenian conscripts from active combat to passive, unarmed logistic sections was an important precursor to the subsequent genocide. As reported in The Memoirs of Naim Bey, the execution of the Armenians in these battalions was part of a premeditated strategy of the CUP. Many of these Armenian recruits were executed by local Turkish gangs.[20]:178

Van, April 1915

The province of Van descended into lawlessness by the end of 1914.[48] Dashnak leaders attempted to keep the situation calm, urging Armenians to tolerate localized massacres because even justifiable self-defense could lead to a generalized massacre.[49] On 19 April 1915, Jevdet Bey demanded that the city of Van immediately furnish him 4,000 soldiers under the pretext of conscription. However, it was clear to the Armenian population that his goal was to massacre the able-bodied men of Van so that there would be no defenders, as had occurred in nearby villages.[20]:202 The Armenians offered five hundred soldiers and exemption money for the rest in order to buy time, but Jevdet Bey accused the Armenians of "rebellion" and asserted his determination to "crush" it at any cost.[50]:205

The next day, 20 April 1915, Ottoman soldiers attacked the Armenian defenses.[51] The Armenian defenders protected the 30,000 residents and 15,000 refugees living in an area of roughly one square kilometer of the Armenian Quarter and suburb of Aigestan. Russian forces liberated Van on 18 May, finding 55,000 corpses in the province, about half its prewar Armenian population.[52][53]

Beginning of deportations

On the night of 23–24 April 1915, known as Red Sunday, the Ottoman government rounded up and imprisoned an estimated 250 Armenian intellectuals and community leaders of the Ottoman capital, Constantinople, and later those in other centers, who were moved to two holding centers near Angora (Ankara).[20]:211–12 This date coincided with Allied troop landings at Gallipoli after unsuccessful Allied naval attempts to break through the Dardanelles to Constantinople in February and March 1915. Following the passage of Tehcir Law on 29 May 1915, the Armenian leaders, except for the few who were able to return to Constantinople, were gradually deported and murdered.[55][56][57] The date 24 April is conventionally held to be the beginning of the genocide.[58] Also on 24 April, Talat ordered that Armenians who had previously been removed from Iskenderun, Dörtyol, Adana, Hadjin, Zeytun, and Sis to be taken to the Syrian Desert rather than central Anatolia, where they would likely have survived.[59] During the next few months deportation was sporadic. After it became clear that other countries would not object strongly, the deportations were speeded in June 1915.[60]

Systematic deportations

On 23 May, Talaat Pasha ordered the deportation of the entire Armenian millet to Deir ez-Zor in the Syrian desert, beginning with the northeastern provinces. The Allies issued a condemnation of Ottoman crimes against Armenians on 24 May, leading the CUP to hastily attempt to disguise the nature of their actions.[61] On 29 May, the CUP Central Committee passed the Temporary Law of Deportation ("Tehcir Law"), giving the Ottoman government and military authorization to deport anyone it "sensed" as a threat to national security.[20]:186–88 Historian Hans-Lukas Kieser states that, from the statements of Talaat Pasha[62] it is clear that the officials were aware that the deportation order was genocidal.[63]

Ottoman records show that the government's goal was to reduce the population of Armenians to no more than 5 to 10 percent in any part of the empire, both in the places from which Armenians were deported and the destination areas. This goal could not be accomplished without mass murder.[64] Deportation was only carried out behind the front lines, where no active rebellion existed. Armenians who lived in the war zone were instead killed in massacres.[65]

Opposition

Talaat ordered the Fourth Army to court-martial any Muslim who collaborated with Christians and Mahmud Kâmil Pasha, commander of the Third Army, ordered that "any Muslim who protected an Armenian [should be] hanged in front of his house".[61] Some politicians tried to prevent the deportations and subsequent massacres. One such politician, Mehmet Celal Bey, was known for saving thousands of lives.[67] When defying the orders of deportation, Celal Bey was removed from his post as governor of Aleppo and transferred to Konya.[21] Nevertheless, as the deportations continued, he repeatedly demanded that the central authorities provide shelter for the deportees.[68] In addition to these demands, he sent the Sublime Porte many telegrams and letters of protest stating that the "measures taken against the Armenians were, from every point of view, contrary to the higher interests of the fatherland."[68] His demands, however, were ignored.[68]

Hasan Mazhar Bey, who was appointed Vali of Ankara on 18 June 1914, also refused to proceed with the order of deportations.[69] Due to his refusal to deport the Armenians, Mazhar Bey was removed from his post as governor in August 1915 and replaced with Atif Bey, a prominent member of the Special Organization.[70] He recalled: "Then one day Atif Bey came to me and orally conveyed the interior minister's orders that the Armenians were to be murdered during the deportation. 'No, Atif Bey,' I said, 'I am a governor, not a bandit, I cannot do this, I will leave this post and you can come and do it.'"[21] Süleyman Nazif, the Vali of Baghdad, who later resigned in protest of the Ottoman government's policy towards the Armenians, wrote in a 28 November 1918 issue of the Hadisat newspaper: "Under the guise of deportations, mass murder was perpetrated. Given the fact that the crime is all too evident, the perpetrators should have been hanged already."[71]

Death marches

The Armenians were marched out to the Syrian town of Deir ez-Zor and the surrounding desert. The Ottoman government deliberately withheld the facilities and supplies that would have been necessary to sustain the life of hundreds of thousands of Armenian deportees during and after their forced march to the Syrian desert.[73][74][75] By August 1915, The New York Times repeated an unattributed report that "the roads and the Euphrates are strewn with corpses of exiles, and those who survive are doomed to certain death. It is a plan to exterminate the whole Armenian people".[76] So many deaths occurred during the marches that the dead bodies of Armenians were left strewn beside the roads. In order to prevent photographs of such atrocities, the Ottoman government ordered that the corpses be cleared as soon as possible.[77]

Rape was an integral part of the genocide;[78] military commanders told their men to "do to [the women] whatever you wish", resulting in widespread sexual abuse. Deportees were displayed naked in Damascus and sold as sex slaves in some areas, including Mosul according to the report of the German consul there, constituting an important source of income for accompanying soldiers.[79] Dr. Walter Rössler, the German consul in Aleppo during the genocide, heard from an "objective" Armenian that around a quarter of young women, whose appearance was "more or less pleasing", were regularly raped by the gendarmes, and that "even more beautiful ones" were violated by 10–15 men. This resulted in girls and women being left behind dying.[80]

It is estimated that less than a quarter of deportees survived the death marches and arrived at their destination.[81]

Concentration camps

A network of 25 concentration camps was set up by the Ottoman government to dispose of the Armenians who had survived the deportations to their ultimate point.[82] This network, situated in the region of Turkey's present-day borders with Iraq and Syria, was directed by Şükrü Kaya, one of Talaat Pasha's right-hand men. Some of the camps were only temporary transit points. Others, such as Radjo, Katma, and Azaz, were briefly used as mass graves and then vacated by autumn 1915. Camps such as Lale, Tefridje, Dipsi, Del-El, and Ra's al-'Ayn were built specifically for those whose life expectancy was just a few days.[83] According to genocide scholar Hilmar Kaiser, the Ottoman authorities refused to provide food and water to the victims, increasing the mortality rate. According to The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies, "Muslims were eager to obtain Armenian women. Authorities registered such marriages but did not record the deaths of the former Armenian husbands."[84]

Bernau, an American citizen of German descent, traveled to the areas where Armenians were incarcerated and wrote a report that was deemed factual by Rössler, the German Consul at Aleppo. He reports mass graves containing over 60,000 people in Meskene and large numbers of mounds of corpses, as the Armenians died due to hunger and disease. He reported seeing 450 orphans, who received at most 150 grams (5.3 oz) of bread per day, in a tent of 5 square metres (54 sq ft) to 6 square metres (65 sq ft). Dysentery swept through the camp and days passed between the instances of distribution of bread to some. In "Abu Herrera", near Meskene, he described how the guards let 240 Armenians starve, and wrote that they searched "horse droppings" for grains.[85]

Massacres

Large parts of the local population willingly participated in massacres.[86]

Mass burnings

Eitan Belkind was a Nili member who infiltrated the Ottoman army as an official. He was assigned to the headquarters of Kemal Pasha. He witnessed the burning of 5,000 Armenians.[87]:181, 183

Lt. Hasan Maruf of the Ottoman army describes how a population of a village were taken all together and then burned.[88] The Commander of the Third Army Vehib's 12-page affidavit, which was dated 5 December 1918, was presented in the Trebizond (Trabzon) trial series (29 March 1919) included in the Key Indictment,[89] reporting such a mass burning of the population of an entire village near Muş: "The shortest method for disposing of the women and children concentrated in the various camps was to burn them".[90] Further, it was reported that "Turkish prisoners who had apparently witnessed some of these scenes were horrified and maddened at remembering the sight. They told the Russians that the stench of the burning human flesh permeated the air for many days after".[91] Genocide scholar Vahakn Dadrian wrote that 80,000 Armenians in 90 villages across the Muş plain were burned in "stables and haylofts".[92]

Drowning

Trebizond (now Trabzon) was the main city in Trebizond Vilayet; Oscar S. Heizer, the American consul at Trebizond, reported: "This plan did not suit Nail Bey ... Many of the children were loaded into boats and taken out to sea and thrown overboard".[93] Hafiz Mehmet, a Turkish deputy serving Trebizond, testified during a 21 December 1918 parliamentary session of the Chamber of Deputies that "the district's governor loaded the Armenians into barges and had them thrown overboard."[94] The Italian consul of Trebizond in 1915, Giacomo Gorrini, writes: "I saw thousands of innocent women and children placed on boats which were capsized in the Black Sea".[95][96] Dadrian places the number of Armenians killed in the Trebizond Vilayet by drowning at 50,000.[92] The Trebizond trials reported Armenians having been drowned in the Black Sea;[97] according to a testimony, women and children were loaded on boats in "Değirmendere" to be drowned in the sea.[98]

Hoffman Philip, the American chargé d'affaires at Constantinople, wrote: "Boat loads sent from Zor down the river arrived at Ana, one thirty miles [50 km] away, with three fifths of passengers missing".[22]:246–47 According to Robert Fisk, 900 Armenian women were drowned in Bitlis, while in Erzincan, the corpses in the Euphrates resulted in a change of course of the river for a few hundred meters.[99] Dadrian also wrote that "countless" Armenians were drowned in the Euphrates and its tributaries.[92]

Killings by physicians

Ottoman physicians contributed to the planning and execution of the genocide. The physicians Behaeddin Shakir and Nazım Bey were leading figures in the leadership committee of the Committee of Union and Progress and both held leadership roles in the Special Organization. Other physicians used their medical expertise to facilitate the killings, including designing methods for poisoning victims and using Armenians as subjects for lethal human experimentation.[100] Morphine overdose,[101] toxic gas,[100] and typhoid inoculation were all reported as methods of killing Armenians.[100] Jeremy Hugh Baron writes: "Individual doctors were directly involved in the massacres, having poisoned infants, killed children and issued false certificates of death from natural causes. Nazim's brother-in-law Dr. Tevfik Rushdu, Inspector-General of Health Services, organized the disposal of Armenian corpses with thousands of kilos of lime over six months; he became foreign secretary from 1925 to 1938".[102]

Confiscation of property

The Tehcir Law brought some measures regarding the property of the deportees, and on 13 September 1915, the Ottoman parliament passed the "Temporary Law of Expropriation and Confiscation," stating that all property, including land, livestock, and homes belonging to Armenians, was to be confiscated by the authorities.[22]:224 Armenians lost their wealth and property without compensation.[104] Businesses and farms were lost, and all schools, churches, hospitals, orphanages, monasteries, and graveyards became Turkish state property.[104] In January 1916, the Ottoman Minister of Commerce and Agriculture issued a decree ordering all financial institutions operating within the empire's borders to turn over Armenian assets to the government.[105] It is recorded that as much as six million Turkish gold pounds were seized along with real property, cash, bank deposits, and jewelry. The assets were then funneled to European banks, including Deutsche and Dresdner banks.[105] After the end of World War I, Genocide survivors tried to return and reclaim their former homes and assets, but were driven out by the Ankara Government.[104]

During the Paris Peace Conference, the Armenian delegation presented an assessment of $3.7 billion (about $55 billion today) worth of material losses owned solely by the Armenian church.[106] The Armenian community then presented an additional demand for the restitution of property and assets seized by the Ottoman government. The joint declaration, which was submitted to the Supreme Council by the Armenian delegation and prepared by the religious leaders of the Armenian community, claimed that the Ottoman government had destroyed 2,000 churches and 200 monasteries and had provided the legal system for giving these properties to other parties.[107] The declaration also provided a financial assessment of the total losses of personal property and assets of both Turkish and Russian Armenia with 14,598,510,000 and 4,532,472,000 francs respectively; totaling to an estimated $354 billion today.[108][109] Furthermore, the Armenian community asked for the restitution of church owned property and reimbursement of its generated income. The Ottoman government never responded to this declaration and so restitution did not occur.[110]

By the early 1930s, all properties belonging to Armenians who were subject to deportation had been confiscated.[111] Since then, no restitution of property confiscated during the Armenian Genocide has taken place.[112] Historians argue that the mass confiscation of Armenian properties was an important factor in forming the economic basis of the Turkish Republic while endowing Turkey's economy with capital. The mass confiscation of properties provided the opportunity for ordinary lower class Turks (i.e. peasantry, soldiers, and laborers) to rise to the ranks of the middle class.[113] Contemporary Turkish historian Uğur Ümit Üngör asserts that "the elimination of the Armenian population left the state an infrastructure of Armenian property, which was used for the progress of Turkish (settler) communities. In other words: the construction of an étatist Turkish "national economy" was unthinkable without the destruction and expropriation of Armenians."[114]

The premeditated destruction of objects of Armenian cultural, religious, historical and communal heritage was yet another key purpose of both the genocide itself and the post-genocidal campaign of denial. Armenian churches and monasteries were destroyed or changed into mosques, Armenian cemeteries flattened, and, in several cities (e.g., Van), Armenian quarters were demolished.[116] In 1914, the Armenian Patriarch in Constantinople presented a list of the Armenian holy sites under his supervision. The list contained 2,549 religious places of which 200 were monasteries while 1,600 were churches. In 1974 UNESCO stated that after 1923, out of 913 Armenian historical monuments left in Eastern Turkey, 464 have vanished completely, 252 are in ruins, and 197 are in need of repair (in stable conditions).[117]

Trials

Turkish courts-martial

On the night of 2–3 November 1918 and with the aid of Ahmed Izzet Pasha, the Three Pashas (which include Mehmed Talaat Pasha and Ismail Enver Pasha, the main perpetrators of the Genocide) fled the Ottoman Empire. In 1919, after the Mudros Armistice, Sultan Mehmed VI was ordered to organise courts-martial by the Allied administration in charge of Constantinople to try members of the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) (Turkish: "Ittihat ve Terakki") for taking the Ottoman Empire into World War I. By January 1919, a report to Sultan Mehmed VI accused over 130 suspects, most of whom were high officials.[119]

Sultan Mehmet VI and Grand Vizier Damat Ferid Pasha, as representatives of government of the Ottoman Empire during the Second Constitutional Era, were summoned to the Paris Peace Conference by US Secretary of State Robert Lansing. On 11 July 1919, Damat Ferid Pasha officially confessed to massacres against the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire and was a key figure and initiator of the war crime trials held directly after World War I to condemn to death the chief perpetrators of the Genocide.[120] The military court found that it was the will of the CUP to eliminate the Armenians physically, via its Special Organization.[121]

The Three Pashas were convicted and sentenced to death in absentia at the trials in Constantinople. The courts-martial officially disbanded the CUP and confiscated its assets and the assets of those found guilty. The courts-martial were dismissed in August 1920 for their lack of transparency, according to then High Commissioner and Admiral Sir John de Robeck,[122] and some of the accused were transported to Malta for further interrogation, only to be released afterwards in an exchange of POWs. Two of the three Pashas were later assassinated by Armenian vigilantes during Operation Nemesis.

Detainees in Malta

Ottoman military members and high-ranking politicians convicted by the Turkish courts-martial were transferred from Constantinople prisons to the Crown Colony of Malta on board the SS Princess Ena and HMS Benbow by the British forces, starting in 1919. Admiral Sir Somerset Gough-Calthorpe, British Commissioner in the Ottoman Empire, was in charge of the operation, together with Lord Curzon; they did so owing to the lack of transparency of the Turkish courts-martial. They were held there for three years, while searches were made of archives in Constantinople, London, Paris and Washington to find a way to put them in trial.[123] However, the war criminals were eventually released without trial and returned to Constantinople in 1921, in exchange for twenty-two British prisoners of war held by the government in Ankara, including a relative of Lord Curzon.[124]

Abandonment of prosecution

The Treaty of Sèvres had planned a trial in August 1920 to determine those responsible for the "barbarous and illegitimate methods of warfare ... [including] offenses against the laws and customs of war and the principles of humanity".[125] Article 230 of the Treaty of Sèvres required the Ottoman Empire to hand over to the Allied Powers the persons responsible for the massacres committed during the war on 1 August 1914.[126] However, the treaty was rejected by the Turkish nationalist movement and replaced by the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923. Annex VIII to that treaty granted immunity to the perpetrators of crimes committed between August 1914 and November 1922.[127][128][129][130][131] On 15 March 1921, former Grand Vizier Talaat Pasha was assassinated in the Charlottenburg District of Berlin, Germany, in broad daylight and in the presence of many witnesses. Talaat's death was part of Operation Nemesis, the Armenian Revolutionary Federation's codename for their covert operation in the 1920s to kill the planners of the Armenian Genocide. In the end, hardly anyone was held accountable for the systematic murder of hundreds of thousands of Armenians.[132]

Demographic losses

The exact number of Armenians who were killed in the genocide is not known and impossible to determine, but most estimates are between 800,000 and over 1 million.[134] Historians estimate that 1.5 to 2 million Armenians lived in the Ottoman Empire in 1915, of which 800,000 to 1.2 million were deported during the genocide.[135] Talat Pasha's estimates, published in 2007, gave an incomplete total of 924,158, which officials' notes suggested to increase by 30 percent. The following estimate of 1.2 million deported is in line with estimates by Johannes Lepsius and Arnold J. Toynbee.[136] Based on contemporary estimates, Akçam estimated that by late 1916, only 200,000 deported Armenians were still alive.[135]

Many of the half million refugees who escaped to the Caucuses, especially the First Republic of Armenia, perished in the famine of 1918–1919 or of disease during that winter.[137] During the 1920 Turkish–Armenian War, 60,000 to 98,000 Armenian civilians were estimated to have been killed by the Turkish army.[138] Some estimates put the total number of Armenians massacred in the hundreds of thousands.[21]:327 Dadrian characterized the massacres in the Caucasus as a "miniature genocide".[22]:360

International reaction

Many foreign officials offered to intervene on behalf of the Armenians, including Pope Benedict XV, only to be turned away by Ottoman government officials who claimed they were retaliating against a pro-Russian insurrection.[139] On 24 May 1915, the Triple Entente warned the Ottoman Empire that "In view of these new crimes of Turkey against humanity and civilization, the Allied Governments announce publicly to the Sublime Porte that they will hold personally responsible for these crimes all members of the Ottoman Government, as well as those of their agents who are implicated in such massacres".[140]

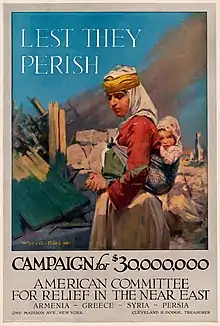

American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief

The American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief (ACASR, later called American Committee for Relief in the Near East (ACRNE) and also known as "Near East Relief"), established in September 1915, was a charitable organization established to relieve the suffering of the peoples of the Near East.[141] The organization was championed by American ambassador Henry Morgenthau, Sr. Morgenthau's dispatches on the mass slaughter of Armenians galvanized much support for the organization.[142]

In its first year, the ACRNE cared for 132,000 Armenian orphans from Tiflis, Yerevan, Constantinople, Sivas, Beirut, Damascus, and Jerusalem. A relief organization for refugees in the Middle East helped donate over $102 million (budget $117,000,000) [1930 value of dollar] to Armenians both during and after the war.[143]:336 Between 1915 and 1930, ACRNE distributed humanitarian relief to locations across a wide geographical range, eventually spending over ten times its original estimate and helping around 2,000,000 refugees.[144]

Austrian and German joint mission

Imperial Germany was allied with the Ottoman Empire during World War I. Some German diplomats openly supported the Ottoman policy against the Armenians. As Hans Humann, the German naval attaché in Constantinople said to US Ambassador Henry Morgenthau:

I have lived in Turkey the larger part of my life ... and I know the Armenians. I also know that both Armenians and Turks cannot live together in this country. One of these races has got to go. And I don't blame the Turks for what they are doing to the Armenians. I think that they are entirely justified. The weaker nation must succumb. The Armenians desire to dismember Turkey; they are against the Turks and the Germans in this war, and they therefore have no right to exist here.[50]:257

In his reports to Berlin in 1917, General Hans von Seeckt supported the reforming efforts of the Young Turks, writing that "the inner weakness of Turkey in their entirety, call for the history and custom of the new Turkish empire to be written".[145] Seeckt added that "Only a few moments of the destruction are still mentioned. The upper levels of society had become unwarlike, the main reason being the increasing mixing with foreign elements of a long standing unculture".[145] Seeckt blamed all of the problems of the Ottoman Empire on the Jews and the Armenians, whom he portrayed as a fifth column working for the Allies.[145] In July 1918, Seeckt sent a message to Berlin stating that "It is an impossible state of affairs to be allied with the Turks and to stand up for the Armenians. In my view any consideration, Christian, sentimental, and political should be eclipsed by a hard, but clear necessity for war".[145]

German aspiring writer Armin T. Wegner enrolled as a medic during the winter of 1914–1915. He defied censorship by taking hundreds of photographs[146] of Armenians being deported and subsequently starving in northern Syrian camps[99]:326 and in the deserts of Deir-er-Zor. Wegner was part of a German detachment under field marshal von der Goltz stationed near the Baghdad Railway in Mesopotamia. He later stated: "I venture to claim the right of setting before you these pictures of misery and terror which passed before my eyes during nearly two years, and which will never be obliterated from my mind.".[147] He was eventually arrested by the Germans and recalled to Germany.

Russian military

The Russian Empire's response to the bombardment of its Black Sea naval ports was primarily a land campaign through the Caucasus. Early victories against the Ottoman Empire from the winter of 1914 to the spring of 1915 saw significant gains of territory, including relieving the Armenian bastion resisting in the city of Van in May 1915. The Russians also reported encountering the bodies of unarmed civilian Armenians as they advanced.[148] In March 1916, the scenes they saw in the city of Erzurum led the Russians to retaliate against the Ottoman III Army whom they held responsible for the massacres, destroying it in its entirety.[149]

Scandinavian missionaries and diplomats

Danish missionary Maria Jacobsen wrote her experiences in a diary entitled Diaries of a Danish Missionary: Harpoot, 1907–1919, which according to genocide scholar Ara Sarafian, is a "documentation of the utmost significance" for research of the Armenian Genocide.[150] Jacobsen would later be known for having saved thousands of Armenians through various relief efforts in the aftermath of the Armenian Genocide .[150][151] She wrote: "It is quite obvious that the purpose of their departure is the extermination of the Armenian people."[151][152] Another missionary who helped save orphans was Anna Hedvig Büll. Another Danish missionary, Aage Meyer Benedictsen, wrote in regards to the massacres that it was a "shattering crime, probably the largest in the history of the world: The attempt, planned and executed in cold blood, to murder a whole people, the Armenian, during the World War."[153]

Persia

Turks and Kurds invaded the town of Salmas in northwestern Persia and massacred the Armenian inhabitants after the withdrawal of Russian troops from the region. Prior to the Russian withdrawal, a larger number of Christians fled across the Arax river into Russia, while a small number remained hidden in the homes of local Muslims.[154]

Studies on the genocide

Polish jurist Raphael Lemkin, who coined the term genocide in 1943, cited the Turkish extermination of the Armenians and the Nazi extermination of the Jews as defining examples of what he meant by genocide. Outraged that there was no legal framework under which to try the perpetrators of such crimes, Lemkin spearheaded the adoption of the 1948 Genocide Convention.[155][156][157] The International Association of Genocide Scholars (IAGS) unanimously passed a formal resolution affirming the factuality of the Armenian Genocide and condemning denial of it.[158] Leading texts in the international law of genocide such as William Schabas's Genocide in International Law cite the Armenian Genocide as precursor to the Holocaust and as a precedent for the law on crimes against humanity.[159] The Armenian Genocide is the second-most studied genocide in history, after the Holocaust.[125][160]

Commemoration and denial

Turkish Government position

No Turkish government has acknowledged that a crime was committed against the Armenian people.[162][163] From the founding of the Republic of Turkey, the genocide has been viewed as a necessity and raison d'état.[164][165] Hans-Lukas Kieser and other historians argue that "the single most important reason for this inability to accept culpability is the centrality of the Armenian massacres for the formation of the Turkish nation-state".[166]

Many leading members of the Turkish nationalist movement had been perpetrators of the genocide, or enriched themselves from it, creating an incentive for silence.[167] Historian Erik-Jan Zürcher argues that "a serious attempt to distance the republic from the genocide could have destabilized the ruling coalition on which the state depended for its stability".[168] Many of the main perpetrators of genocide, including Talat Pasha, were hailed as national heroes of Turkey. Those convicted and executed for war crimes, such as Mehmet Kemal and Behramzade Nusret, were proclaimed "national" and "glorious" martyrs, and schools and neighborhoods were named after them.[169][170] The word "Armenian" became one of the worst insults in the Turkish language.[171]

Talat Pasha had decreed that "everything must be done to abolish even the word 'Armenia' in Turkey".[172] In the postwar Turkish republic, Armenian cultural heritage has been subject to systematic destruction as an attempt to eradicate any traces of the Armenian presence.[173][172][174] On 5 January 1916, Enver Pasha ordered all place names of Greek, Armenian, or Bulgarian origin to be changed, a policy which was fully implemented in the later republic, continuing into the 1980s.[175] For decades, Turkish school textbooks omitted any mention of Armenians as part of Ottoman history.[176] More recently Armenians have been presented as enemies who committed genocide against Turks.[177]

Turkey's century-long effort to deny the Armenian Genocide is an important aspect of its foreign policy.[178] According to Colin Tatz, "No other nation in history has so aggressively sought the suppression of a slice of its history".[179][180] Its efforts to prevent any recognition or mention of the genocide in foreign countries have included millions of dollars in lobbying,[181] withdrawal of ambassadors,[182] intimidation and threats,[183] and suggesting that Turkish Jews would not be safe if the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum covered the Armenian Genocide.[184] Historian Donald Bloxham recognizes that since "denial has always been accompanied by rhetoric of Armenian treachery, aggression, criminality, and territorial ambition, it actually enunciates an ongoing if latent threat of Turkish 'revenge'".[185] Akçam states: "If a society, if a state, doesn’t acknowledge its wrongdoing in the past, this means there is a potential there, always, that it can do it again."[186]

Armenian position

In 1965, the 50th anniversary of the genocide, a 24-hour mass protest was initiated in Yerevan demanding recognition of the Armenian Genocide by Soviet authorities.[187]:88–108 A memorial was completed two years later, at Tsitsernakaberd above the Hrazdan gorge in Yerevan. The memorial contains a 44 metres (144 ft) stele which symbolizes the national rebirth of Armenians. Twelve slabs are positioned in a circle, representing 12 lost provinces in present-day Turkey. At the center of the circle there is an eternal flame. Each 24 April, hundreds of thousands of people walk to the monument, which is the official memorial of the genocide, and lay flowers around the eternal flame.[188]

Visits to the museum are a part of the protocol of the Republic of Armenia. Many foreign dignitaries have already visited the Museum, including Pope John Paul II, Pope Francis, President of the Russian Federation Vladimir Putin, Presidents of France Jacques Chirac, François Hollande and other well-known public and political figures. The museum is open to the public for guided tours in Armenian, Russian, English, French, and German.[189] The worldwide recognition of the Genocide is a core aspect of Armenia's foreign policy.[190]

Armenia has been involved in a protracted ethnic-territorial conflict with Azerbaijan, a Turkic state, since Azerbaijan became independent from the Soviet Union in 1991. The conflict has featured massacres and ethnic cleansing by both sides. Some foreign policy observers and historians have suggested that Armenia and the Armenian diaspora have sought to portray the modern conflict as a continuation of the Armenian Genocide, in order to influence modern policy-making in the region.[191][192]:232–3 According to Thomas Ambrosio, the Armenian Genocide furnishes "a reserve of public sympathy and moral legitimacy that translates into significant political influence ... to elicit congressional support for anti-Azerbaijan policies".[192] The rhetoric leading up to the onset of the conflict, which unfolded in the context of several pogroms against Armenians, was dominated by references to the Armenian Genocide, including fears that it would be, or was in the course of being, repeated.[193] During the conflict, the Azeri and Armenian governments regularly accused each other of genocidal intent, although these claims have been treated skeptically by outside observers.[191]:232–33

International recognition

As a response to continuing denial by the Turkish state, many activists from Armenian Diaspora communities have pushed for formal recognition of the Armenian Genocide from various governments around the world. On 4 March 2010, a U.S. congressional panel narrowly voted that the incident was indeed genocide; within minutes the Turkish government issued a statement critical of "this resolution which accuses the Turkish nation of a crime it has not committed". The Armenian Assembly of America (AAA) and the Armenian National Committee of America (ANCA) have as their main lobbying agenda to press Congress and the President for an increase of economic aid for Armenia and the reduction of economic and military assistance for Turkey. The efforts also include reaffirmation of a genocide by Ottoman Turkey in 1915.[194] Over 135 memorials, spread across 25 countries, commemorate the Armenian Genocide.[195]

Twenty-nine countries and forty-nine U.S. states have adopted resolutions acknowledging the Armenian Genocide as a bona fide historical event.[196] In October 2019, the United States House of Representatives voted 405–11 to officially recognize the mass killing of Armenians by Turkish nationalists during World War I as "genocide" (H.Res. 296).[197][198] The United States Senate also passed a unanimous resolution in recognition of the Armenian Genocide despite President Donald Trump's objections.[199]

Pope Francis described the Armenian Genocide as the "first genocide of the 20th century", causing a diplomatic row with Turkey. He also called on all heads of state and international organizations to recognize "the truth of what transpired and oppose such crimes without ceding to ambiguity or compromise."[200] In a resolution, the European Parliament commended the statement pronounced by the Pope and encouraged Turkey to recognise the genocide and so pave the way for a "genuine reconciliation between the Turkish and Armenian peoples".[201]

Media portrayal

The first artwork known to have been influenced by the Armenian Genocide was a medal struck in St. Petersburg while the massacres and deportations of 1915 were at their height. It was issued as a token of Russian sympathy for Armenian suffering. Since then, dozens of similar medals have been commissioned in various countries.[202]

Numerous eyewitness accounts of the atrocities were published, notably those of Swedish missionary Alma Johansson and U.S. Ambassador Henry Morgenthau, Sr. German medic Armin Wegner wrote several books about the atrocities he witnessed while stationed in the Ottoman Empire. Years later, having returned to Germany, Wegner was imprisoned for opposing Nazism,[203] and his books were burnt by the Nazis.[204] Probably the best known literary work on the Armenian Genocide is Franz Werfel's 1933 The Forty Days of Musa Dagh. This book was a bestseller that became particularly popular among the youth in the Jewish ghettos during the Nazi era.[87]:302–04

Kurt Vonnegut's 1988 novel Bluebeard features the Armenian Genocide as an underlying theme.[205] Other novels incorporating the Armenian Genocide include Louis de Berniéres' Birds without Wings, Edgar Hilsenrath's German-language The Story of the Last Thought, and Polish Stefan Żeromski's 1925 The Spring to Come. A story in Edward Saint-Ivan's 2006 anthology "The Black Knight's God" includes a fictional survivor of the Armenian Genocide.

The first feature film about the Armenian Genocide, a Hollywood production titled Ravished Armenia, was released in 1919. It was produced by the American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief and based on the account of survivor Aurora Mardiganian, who played herself. It resonated with acclaimed director Atom Egoyan, influencing his 2002 Ararat. Several movies are based on the Armenian Genocide including the 2014 drama film The Cut,[206] 1915 The Movie,[207] and The Promise.[208] There are also references to the Genocide in Elia Kazan's America, America and Henri Verneuil's Mayrig. At the Berlin International Film Festival of 2007 Italian directors Paolo and Vittorio Taviani presented another film about the atrocities, based on Antonia Arslan's book, La Masseria Delle Allodole (The Farm of the Larks).[209]

The paintings of Armenian-American Arshile Gorky, a seminal figure of Abstract Expressionism, are considered to have been influenced by the suffering and loss of the period.[210] In 1915, at age 10, Gorky fled his native Van and escaped to Russian-Armenia with his mother and three sisters, only to have his mother die of starvation in Yerevan in 1919. His two The Artist and His Mother paintings are based on a photograph with his mother taken in Van.[211]

Notes

References

- The Armenian genocide : history, politics, ethics. Hovannisian, Richard G. New York: St. Martin's Press. 1992. p. xvi. ISBN 0312048475. OCLC 23768090.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Ihrig, Stefan (2016). Justifying Genocide: Germany and the Armenians from Bismarck to Hitler. Harvard University Press. pp. 9, 55. ISBN 978-0-674-50479-0.

- Stanley, Alessandra (17 April 2006). "A PBS Documentary Makes Its Case for the Armenian Genocide, With or Without a Debate". The New York Times.

- de Waal 2015, pp. 257–258.

- Robertson, Geoffrey (2016). "Armenia and the G-word: The Law and the Politics". The Armenian Genocide Legacy. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 69–83. ISBN 978-1-137-56163-3.

Put another way – if these same events occurred today, there can be no doubt that prosecutions before the ICC of Talaat and other CUP officials for genocide, for persecution and for other crimes against humanity would succeed. Turkey would be held responsible for genocide and for persecution by the ICJ and would be required to make reparation.

- Lattanzi, Flavia (2018). "The Armenian Massacres as the Murder of a Nation?". The Armenian Massacres of 1915–1916 a Hundred Years Later: Open Questions and Tentative Answers in International Law. Springer International Publishing. pp. 27–104. ISBN 978-3-319-78169-3.

- Laycock, Jo (2016). "The great catastrophe". Patterns of Prejudice. 50 (3): 311–313. doi:10.1080/0031322X.2016.1195548. S2CID 147933878.

important developments in the historical research on the genocide over the last fifteen years... have left no room for doubt that the treatment of the Ottoman Armenians constituted genocide according to the United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide

- de Waal, Thomas (2015). Great Catastrophe: Armenians and Turks in the Shadow of Genocide. Oxford University Press. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-19-935069-8.

- Mouradian, Khatchig (23 September 2006). "Explaining the Unexplainable: The Terminology Employed by the Armenian Media when Referring to 1915". The Armenian Weekly.

- Matiossian, Vartan (15 May 2013). "The 'Exact Translation': How 'Medz Yeghern' Means Genocide". The Armenian Weekly.

- Simone, Pierluigi. "Is the Denial of the "Armenian Genocide" an Obstacle to Turkey's Accession to the EU?". The Armenian Massacres of 1915–1916 a Hundred Years Later: Open Questions and Tentative Answers in International Law. Springer International Publishing. pp. 275–297 [277]. ISBN 978-3-319-78169-3.

- "Prof. Taner Akçam receives 'Heroes of Justice and Truth' award during Armenian Genocide Centennial commemoration". Clark Now. 28 May 2015. Retrieved 20 November 2020.

The Turkish government persists in its long-standing refusal to call the killings genocide, denying the claims as “Armenian lies.”

- Suny 1993, pp. 3, 30.

- Suny 2015, p. xiv.

- Herzig, Edmund; Kurkchiyan, Marina (2004). The Armenians: Past and Present in the Making of National Identity. Routledge. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-135-79837-6.

- Khachaturian, Lisa (2011). Cultivating Nationhood in Imperial Russia: The Periodical Press and the Formation of a Modern Armenian Identity. Transaction Publishers. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-4128-1372-3.

- Barsoumian, Hagop (1982), "The Dual Role of the Armenian Amira Class within the Ottoman Government and the Armenian Millet (1750–1850)", in Braude, Benjamin; Lewis, Bernard (eds.), Christians and Jews in the Ottoman Empire: The Functioning of a Plural Society, I, New York: Holmes & Meier

- Barsoumian, Hagop (1997), "The Eastern Question and the Tanzimat Era", in Hovannisian, Richard G (ed.), The Armenian People From Ancient to Modern Times, II: Foreign Dominion to Statehood: The Fifteenth Century to the Twentieth Century, New York: St. Martin's, pp. 175–201, ISBN 0-312-10168-6

- Gábor Ágoston; Bruce Alan Masters (2010). Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. Infobase Publishing. p. 185. ISBN 978-1-4381-1025-7.

- Balakian, Peter (2003). The Burning Tigris: The Armenian Genocide and America's Response. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-019840-0.

- Akçam, Taner (2006). A Shameful Act: The Armenian Genocide and the Question of Turkish Responsibility. New York: Metropolitan Books. pp. 1–93. ISBN 0-8050-7932-7.

“Right to intervene”.

- Dadrian, Vahakn N. (1995). The History of the Armenian Genocide: Ethnic Conflict from the Balkans to Anatolia to the Caucasus. Oxford: Berghahn Books. ISBN 1-57181-666-6.

- Suny 1993, p. 101.

- Suny 2015, p. 48.

- Elik, Suleyman (2013). Iran-Turkey Relations, 1979–2011: Conceptualising the Dynamics of Politics, Religion and Security in Middle-Power States. Routledge. p. 12. ISBN 978-1136630880.

- Nalbandian, Louise (1963), The Armenian Revolutionary Movement: The Development of Armenian Political Parties through the Nineteenth Century, Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 0520009142

- Libaridian, Gerard (2011). "What was Revolutionary about Armenian Revolutionary Parties in the Ottoman Empire?". In Suny, Ronald; et al. (eds.). A Question of Genocide: Armenians and Turks at the End of the Ottoman Empire. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 82–112. ISBN 978-0195393743.

- "The Graphic". 7 December 1895. p. 35. Retrieved 5 February 2018 – via The British Newspaper Archive.

- "Armenian Genocide". history.com. History.

The German Foreign Ministry operative, Ernst Jackh, estimated that 200,000 Armenians were killed and a further 50,000 expelled from the provinces during the Hamidian unrest. French diplomats placed the figures at 250,000 killed. The German pastor Johannes Lepsius was more meticulous in his calculations, counting the deaths of 88,000 Armenians and the destruction of 2,500 villages, 645 churches and monasteries, and the plundering of hundreds of churches, of which 328 were converted into mosques. - "Young Turk Revolution". matrix.msu.edu. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 13 December 2015.

- "Details of Slaughter Received". The New York Times. 5 May 1909. Retrieved 17 February 2018.

Cited in Shirinian, George N. (2017). Genocide in the Ottoman Empire: Armenians, Assyrians, and Greeks, 1913–1923. Berghahn Books. p. 121. ISBN 978-1785334337. - "30,000 Killed in massacres; Conservative estimate of victims of Turkish fanaticism in Adana Vilayet". The New York Times. 25 April 1909.

- Walker, Christopher J. "World War I and the Armenian Genocide". The Armenian People from Ancient to Modern Times. II. p. 244.

- Chorbajian, Levon (2016). "'They Brought It on Themselves and It Never Happened': Denial to 1939". The Armenian Genocide Legacy. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 167–182. ISBN 978-1-137-56163-3.

- "La Turchia in guerra " in "Pro Familia", Milanօ, 17 Geniano, 1915 pp. 38–42

"Berliner Morgenpost", " Der Heilige Krieg der Muselmanen", 14 November 1914

Ludke T., Jihad made in Germany, Ottoman and German Propaganda and Intelligence Operations in the First World War, Transaction Publishers, 2005, pp. 12–13

Vahakn Dadrian, The History of the Armenian Genocide. Ethnic Conflict from the Balkans to Anatolia to eh Caucasus, Berghahn Books, Oxford, 1995, pp. 3–6 - Libaridian, Gerard J (2000). "The Ultimate Repression: The Genocide of the Armenians, 1915-1917". In Walliman, Isidor; Dobkowski, Michael N (eds.). Genocide and the Modern Age. Syracuse, New York. p. 224. ISBN 0-8156-2828-5.

- Zayas, Alfred M. De (2005). The Genocide Against the Armenians 1915-1923 and the Relevance of the 1948 Genocide Convention. European Armenian Federation for Justice and Democracy. p. 6.

- Akçam, Taner (2019). "When Was the Decision to Annihilate the Armenians Taken?". Journal of Genocide Research. 21 (4): 457–480. doi:10.1080/14623528.2019.1630893. S2CID 199042672.

- "Armenia". Holocaust and Genocide Studies | College of Liberal Arts. University of Minnesota. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- Melson, Robert (2013). "Recent Developments in the Study of the Armenian Genocide". Holocaust and Genocide Studies. 27 (2): 313–321 [315]. doi:10.1093/hgs/dct036. S2CID 143535027.

There is widespread agreement among scholars that the Young Turks did not have a policy of genocide in place before the war. Death and destruction were the byproducts of the deportations, not the results of a prewar conspiracy.

- Libaridian, Gerard J (2000). "The Ultimate Repression: The Genocide of the Armenians, 1915-1917". In Walliman, Isidor; Dobkowski, Michael N (eds.). Genocide and the Modern Age. Syracuse, New York. p. 223. ISBN 0-8156-2828-5.

- Forsythe, David P. (11 August 2009). Encyclopedia of human rights. 1. Oxford University Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-19-533402-9 – via Google Books.

- Dadrian, Vahakn (November 1991). "The Documentation of the World War I Armenian Massacres in the Proceedings of the Turkish Military Tribunal". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 23 (4): 549–76 [560]. doi:10.1017/S0020743800023412. JSTOR 163884.

- Kevorkian, Raymond (2011). The Armenian Genocide: A Complete History. I.B.Tauris. p. 432. ISBN 978-0857730206.

- Rummel, Rudolf J. (2005). Genocide never again (book 5) (PDF). Llumina Press. ISBN 1-59526-075-7. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- Suny 2015, p. 244.

- Toynbee, Arnold Joseph; Bryce, James Bryce (1915). Armenian atrocities, the murder of a nation. University of California Libraries. London, New York [etc.] : Hodder & Stoughton. pp. 81–82.

- Suny 2015, p. 253.

- Suny 2015, p. 255.

- Morgenthau, Henry (2010) [First published 1918]. Ambassador Morgenthau's Story: A Personal Account of the Armenian Genocide. Cosimo, Inc. ISBN 978-1-61640-396-6. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- Suny 2015, p. 257.

- Hinterhoff, Eugene. Persia: The Stepping Stone To India. Marshall Cavendish Illustrated Encyclopedia of World War I. iv. pp. 153–57.

- Suny 2015, pp. 259–260.

- "Ottoman military forces march Armenian men from Kharput to an execution site outside outside the city. Kharput, Ottoman Empire, March 1915-June 1915". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- Ugur Ungor; Mehmet Polatel (2011). Confiscation and Destruction: The Young Turk Seizure of Armenian Property. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-4411-1020-6.

...were rounded up and deported to the interior where most were murdered.

- Heather Rae (2002). State Identities and the Homogenisation of Peoples. Cambridge University Press. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-521-79708-5.

on the night of 23–24 April 1915 with the arrest of hundreds of intellectuals and leaders of the Armenian community in [...] They were deported to Anatolia where they were put to death.

- Alan Whitehorn (2015). The Armenian Genocide: The Essential Reference Guide. ABC-CLIO. p. 139. ISBN 978-1-61069-688-3.

That particular date was chosen because on April 24, 1915, the Ottoman Young Turk government began deporting hundreds of Armenian leaders and intellectuals from Constantinople (Istanbul); most were later murdered en masse.

- Adalian, Rouben Paul (2013). "The Armenian Genocide". In Totten, Samuel; Parsons, William Spencer (eds.). Centuries of Genocide: Essays and Eyewitness Accounts. Routledge. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-415-87191-4.

- Suny 2015, pp. 274–275.

- Dadrian, Vahakn (1998). "The Historical and Legal Interconnections Between the Armenian Genocide and the Jewish Holocaust: From Impunity to Retributive Justice". Yale Journal of International Law. 23 (2): 509. ISSN 0889-7743.

- Üngör, Uğur Ümit (2008). "Seeing like a nation-state: Young Turk social engineering in Eastern Turkey, 1913–50". Journal of Genocide Research. 10 (1): 15–39 [24]. doi:10.1080/14623520701850278. S2CID 71551858.

- Kabacali, Alpay (1994). Talat Paşa'nın hatıraları [Talaat Pasha's memoirs] (in Turkish). İletişim Yayınları. ISBN 978-9754700459.

- "Ermeni Meselesi" (PDF) (in Turkish). Hist.net. 11 March 2001. p. 12. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 16 December 2018.

- Akçam 2012, p. 242.

- Kaiser, Hilmar (15 April 2010). "Genocide at the Twilight of the Ottoman Empire". In Bloxham, Donald; Moses, A. Dirk (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-923211-6.

- Derived from map 224 in Hewsen, Robert H.; Salvatico, Christopher C. (2001). Armenia : a historical atlas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 224. ISBN 0-226-33228-4. OCLC 995496723.

- "Türk Schindler'i: Vali Celal Bey". NTVMSNBC (in Turkish). 4 August 2010.

- Derogy, Jacques (1990). Resistance and Revenge: The Armenian Assassination of the Turkish Leaders Responsible for the 1915 Massacres and Deportations. Transaction Publishers. p. 32. ISBN 1-4128-3316-7.

- Bedrosyan, Raffi (29 July 2013). "The Real Turkish Heroes of 1915". The Armenian Weekly.

- Hull, Isabel V. (2013). Absolute Destruction: Military Culture and the Practices of War in Imperial Germany. Cornell University Press. p. 273. ISBN 978-0-8014-6708-0.

- Dadrian, Vahakn N.; Akçam, Taner (2011). Judgment at Istanbul the Armenian genocide trials (English ed.). New York: Berghahn Books. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-85745-286-3.

- US Library of Congress, George Grantham Bain Collection Photo ID LC-USZ62-48100 "Syria – Aleppo – Armenian woman kneeling beside dead child in field "within sight of help and safety at Aleppo"

- "Exiled Armenians starve in the desert; Turks drive them like slaves, American committee hears ;- Treatment raises death rate". The New York Times. 8 August 1916. Archived from the original on 2 February 2012. (cited by McCarthy, Justin (2010). The Turk in America: The Creation of an Enduring Prejudice. University of Utah Press. p. 177. ISBN 978-1607810131.)

- Danieli, Yael (1998). International Handbook of Multigenerational Legacies of Trauma. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 23. ISBN 978-0306457388.

[Victims] were often held without food for days so they would be too weak to escape

- Bartrop, Paul R.; Jacobs, Steven Leonard (17 December 2014). Modern Genocide: The Definitive Resource and Document Collection. ABC-CLIO. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-61069-364-6.

- Horvitz, Leslie Alan; Catherwood, Christopher (2014). Encyclopedia of War Crimes and Genocide. Infobase Publishing. p. 26. ISBN 978-1438110295.

Primary source: "Armenians are sent to perish in desert; Turks accused of plan to exterminate whole population; people of Karahissar massacred". The New York Times. 18 August 1915. - Akçam, Taner (2018). Killing Orders: Talat Pasha's Telegrams and the Armenian Genocide. Springer. p. 158. ISBN 978-3-319-69787-1.

- Von Joeden-Forgey, Elisa (2010). "Gender and Genocide". In Donald Bloxham, A. Dirk Moses (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies. Oxford University Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-19-923211-6.

- Akçam, Taner (2012). The Young Turks' Crime against Humanity: The Armenian Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing in the Ottoman Empire. Princeton University Press. pp. 312–315. ISBN 978-0-691-15333-9.

- Gust, Wolfgang (2013). The Armenian Genocide: Evidence from the German Foreign Office Archives, 1915–1916. Berghahn Books. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-1-78238-143-3.

- Bjørnlund, Matthias (2009). "'A Fate Worse Than Dying': Sexual Violence during the Armenian Genocide". Brutality and Desire: War and Sexuality in Europe's Twentieth Century. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 16–58. ISBN 978-0-230-23429-1.

- "L'extermination des déportés Arméniens ottomans dans les camps de concentration de Syrie-Mésopotamie (1915–1916)". imprescriptible.fr (in French). Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- Kotek, Joël; Rigoulot, Pierre (2000). Le siècle des camps (in French). JC Lattès. ISBN 2-7096-4155-0.

- Kaiser, Hilmar (2010). "18. Genocide at the Twilight of the Ottoman Empire". In Donald Bloxham (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies. A. Dirk Moses. OUP Oxford. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-19-161361-6. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- Gust, Wolfgang (2013). The Armenian Genocide: Evidence from the German Foreign Office Archives, 1915–191. Berghahn Books. pp. 653–54. ISBN 978-1-78238-143-3.

- Dadrian, Vahakn N. (2004). "Patterns of twentieth century genocides: the Armenian, Jewish, and Rwandan cases". Journal of Genocide Research. 6 (4): 487–522 [490]. doi:10.1080/1462352042000320583. S2CID 72220367.

By Turkish admissions, large segments of the provincial population in particular willingly participated in regional and local massacres.

- Auron, Yair (2000). "The Banality of Indifference: Zionism and the Armenian Genocide". New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - British Foreign Office 371/2781/264888, Appendices B., p. 6.

- Takvimi Vekayi, No. 3540, 5 May 1919.

- McClure, Samuel S. Obstacles to Peace. Boston, New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1917, pp. 400–01.

- Viscount Bryce (1916). "The Treatment of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire 1915–16: Documents presented to Viscount Grey of Falloden, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs". New York and London: GP Putnam's Sons, for His Majesty's Stationery Office. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)

"Death toll of the Armenian Massacres". Encyclopædia Britannica. - Charny, Israel W.; Tutu, Desmond; Wiesenthal, Simon (2000). Encyclopedia of genocide (Repr ed.). Oxford: ABC-Clio. p. 95. ISBN 0-87436-928-2.

- Kiernan, Ben (2007). Blood and Soil: A World History of Genocide and Extermination from Sparta to Darfur. Yale University Press. pp. 411–12. ISBN 978-0300100983.

- Winter, Jay (2004). America and the Armenian Genocide of 1915. Cambridge University Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-139-45018-8.

- "Turks Slay 14,000 In One Massacre". Toronto Globe. 26 August 1915. p. 1.