Astley Hall, Chorley

Astley Hall is a country house in Chorley, Lancashire, England. The hall is now owned by the town and is known as Astley Hall Museum and Art Gallery. The extensive landscaped grounds are now Chorley's Astley Park.

| Astley Hall | |

|---|---|

| |

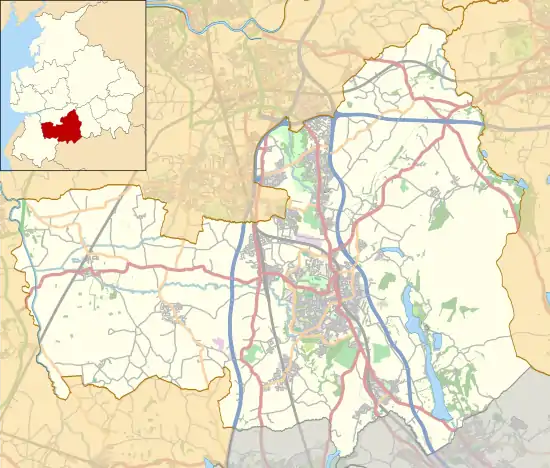

Location in the Borough of Chorley | |

| Alternative names | Astley Hall Museum and Art Gallery |

| General information | |

| Type | Country house |

| Architectural style | Renaissance |

| Town or city | Chorley, Lancashire |

| Country | England |

| Coordinates | 53.6595°N 2.6453°W |

| Construction started | c. 1570 |

| Completed | 1630, 1653 or 1666[1] |

| Renovated | 1949 |

| Owner | Chorley Borough Council |

| Technical details | |

| Material | Stone |

| Website | |

| www | |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Designated | 21 December 1966 |

| Reference no. | 1362068 |

History

The site was acquired in the 15th century by the Charnock family from the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem. The Charnocks built the original timber-framed house, around a small courtyard, about 1575-1600. In 1665, Margaret Charnock married Richard Brooke of Mere in Cheshire (son of Sir Peter Brooke), and they built the present grand but asymmetrical front range of brick with a pair of vast mullion and transomed bay windows. This front has a doorway with distinctly rustic Ionic columns, remarkable at such a late date.

The interior is notable for the staggering mid-17th century plasterwork in the ceilings of the Great Hall and drawing room, which have heavy wreaths and disporting cherubs.[2] The ceilings are barbaric in their excesses, and the figures are relatively poorly modelled, although the undercutting is breathtaking. Not all the moulding is of stucco: there are elements of lead and leather too. The staircase is of the same period with a coarse but vigorously carved acanthus scroll balustrade and square newels with vases of flowers on top.

The lower parts of the hall are panelled with inset paintings of a curious selection of modern worthies, including Protestants such as Elizabeth I and William the Silent; Catholics such as Philip II and Ambrogio Spinola; the explorers Christopher Columbus and Ferdinand Magellan, and Muhammadans such as Bajazet and Mohammed II, Sultans of Turkey; it is thought this scheme might be rather earlier than the other work and date from the time of MP Thomas Charnock, who died in 1648. The entire width of the house on the top floor is occupied by a long gallery which contains the finest shovelboard table in existence, 23.5 feet (7.2 m) long.

The house contains a bird's-eye view by an unknown artist showing the house c. 1710, which depicts small tower-gazebos at the angles of its forecourt. In due course, the Brookes failed in the male line and the house descended to Robert Townley Parker of Cuerden, who added the south wing in 1825 and stuccoed the exterior, probably to the design of Lewis Wyatt, who worked for Parker at Cuerden Hall. The dining room in the early 19th-century wing has inlaid 16th-century panelling brought in from elsewhere.

In 1864, the will of alkali manufacturer John Hutchinson of Widnes named one of his executors as "Thomas Part of Astley Hall in Chorley", although Thomas Part may well not have been the owner at the time.

In 1922 the house and its contents were given to Chorley Corporation by Reginald Tatton, as a memorial to the local men killed in World War I. It has since been maintained as a museum. The house contains fine oak furniture, Flemish tapestries and wooden panelling. It is rumoured that Oliver Cromwell stayed at the Hall during the Battle of Preston in the 17th century and reportedly left his boots behind. However, recent research shows that these may not be his own boots, although this does not rule out him visiting the Hall. A wide range of temporary exhibitions are displayed in the art gallery throughout the season and events are organised throughout the year.

The plain classical brick stable block with pedimented centre is of c. 1800.

The grounds with a small lake were landscaped by John Webb and feature a picturesque meandering stream running through a wooded ravine.

The Park, Coach House and Walled Garden have recently been renovated with help from the Heritage Lottery Fund and Chorley Council. An extensive project has seen the restoration of the 17th century ha-ha, de-silting of the lake, felling of trees, moving pets corner and extensive renovation of the coach house and walled garden. The Coach House now houses a new art gallery and conference room on the first floor, with a cafe and education space on the ground floor.

Previous owners

- Robert Charnock (d. 1616);

- Richard Charnock MP (d.1648/1653), 1616-48/53;

- Margaret Charnock, wife of Richard Brooke (1640–1715), 1648/53-1715;

- Peter Brooke, son (1673–1721), 1715–21;

- Thomas Brooke, brother (1684–1734), 1721–34;

- Richard Brooke, son (1717–48), 1734–48;

- Peter Brooke, brother (d.1786), 1748–86;

- Peter Brooke, son (1764–87), 1786–87;

- Susannah Brooke, sister (1762–1852), wife of Thomas Townley Parker (1760–94), 1787-?;

- Robert Townley Parker, son (1793–1879), ?-1879;

- Thomas Townley Parker, son (1822–1906), 1879–1906;

- Reginald Arthur Tatton, nephew (1857–1926), 1906–22;

- Chorley Borough Council in association with Russ Astley, 1922–present.

Present

The Hall is owned and managed by Chorley Council. It is used as a museum but can also be rented for functions and is open to the public at weekends. There is no charge for public entrance.[2]

Opened in 2013, The Chorley Remembers Experience is a 500-square feet exhibition and display space, divided into three "zones" – remembrance, conflicts and activity, which focusses on Chorley's involvement and military history over the years.[3] The experience is run by the Trustees of the Chorley Pals Memorial.[2]

The permanent exhibition which is located within the coach house at Astley Hall was built and installed by Heckford.[4]

Additional funding for the project was awarded by the Heritage Lottery Fund.[2]

Gallery

The Stucco Room

The Stucco Room The Cromwell Room

The Cromwell Room The Oak Bedroom

The Oak Bedroom The Long Gallery

The Long Gallery The Ante Room

The Ante Room The Inlaid Room

The Inlaid Room The Dining Room

The Dining Room The Courtyard

The Courtyard The Kitchen

The Kitchen The Morning Room

The Morning Room The Great Hall

The Great Hall The Drawing Room

The Drawing Room The exterior of Astley Hall

The exterior of Astley Hall

See also

References

- Historic England. "Astley Hall (1362068)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- "Astley Hall". Borough of Chorley. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- "Interactive exhibition in Chorley brings to life untold stories of war". Newsquest. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- "Heckford Exhibitions commemorates Chorley war heroes". Haymarket. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- Sir H. Colvin, A biographical dictionary of British architects, 1600–1840, p. 1043

- Country Life, 1922, vol. 51, p. 284; vol. 52, pp. 14, 50, 127; Country Life, 1924, vol. 56, pp. 339, 491; Country Life, 1955, vol. 118, p. 1214

- N. Cooper, Houses of the Gentry, 1480–1680, 1999, p. 321

- J. Harris, The artist and the country house, 1985, pp. 97, 143

- Timothy Mowl & Brian Earnshaw Architecture without kings, 1995, p. 174

- J.M. Robinson, The country houses of the north-west, 1991, pp. 154–155

External links

- Astley Hall Museum and Art Gallery - official site

- Manchester Region History Review, Volume 12 1998, Astley Hall Museum and Art Gallery, Nigel Wright

- Astley Park

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Astley Hall. |