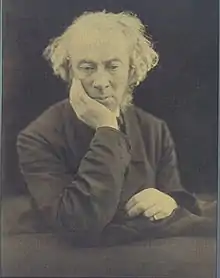

Aubrey Thomas de Vere

Aubrey Thomas de Vere (10 January 1814 – 20 January 1902) was an Irish poet and critic.[1]

Life

Aubrey Thomas Hunt de Vere was born at Curraghchase House (now in ruins) at Curraghchase, Kilcornan, County Limerick,[2] the third son of Sir Aubrey de Vere, 2nd Baronet (1788–1846) and his wife Mary Spring Rice, daughter of Stephen Edward Rice (d.1831) and Catherine Spring,[3] of Mount Trenchard, Co. Limerick. He was a nephew of Lord Monteagle, a younger brother of Sir Stephen de Vere, 4th Baronet and a cousin of Lucy Knox. His sister Ellen married Robert O'Brien, the brother of William Smith O'Brien.[4] In 1832, his father dropped the original surname 'Hunt' by royal licence, assuming the surname 'de Vere'.

He was strongly influenced by his friendship with the astronomer, Sir William Rowan Hamilton, through whom he came to a knowledge and reverent admiration for Wordsworth and Coleridge. He was educated privately at home and in 1832 entered Trinity College, Dublin, where he read Kant and Coleridge. Later he visited Oxford, Cambridge, and Rome, and came under the potent influence of John Henry Newman. He was also a close friend of Henry Taylor.[5]

The characteristics of Aubrey de Vere's poetry are high seriousness and a fine religious enthusiasm. His research in questions of faith led him to the Roman Catholic Church where in 1851 he was received into the Church by Cardinal Manning in Avignon.[6] In many of his poems, notably in the volume of sonnets called St Peters Chains (1888), he made rich additions to devotional verse. For a few years he held a professorship, under Newman, in the Catholic University in Dublin.[5]

In "A Book of Irish Verse," W. B. Yeats described de Vere's poetry as having "less architecture than the poetry of Ferguson and Allingham, and more meditation. Indeed, his few but ever memorable successes are enchanted islands in gray seas of stately impersonal reverie and description, which drift by and leave no definite recollection. One needs, perhaps, to perfectly enjoy him, a Dominican habit, a cloister, and a breviary."

He also visited the Lake Country of England, and stayed under Wordsworth's roof, which he called the greatest honour of his life. His veneration for Wordsworth was singularly shown in later life, when he never omitted a yearly pilgrimage to the grave of that poet until advanced age made the journey impossible.[7]

He was of tall and slender physique, thoughtful and grave in character, of exceeding dignity and grace of manner, and retained his vigorous mental powers to a great age. According to Helen Grace Smith, he was one of the most profoundly intellectual poets of his time.[7] His census return for 1901 lists his profession as 'Author.'[8]

He died at Curraghchase in 1902, at the age of eighty-eight. As he never married, the name of de Vere at his death became extinct for the second time, and was assumed by his nephew.[7]

Works

His best-known works are: in verse, The Sisters (1861); The Infant Bridal (1864); Irish Odes (1869); Legends of St Patrick (1872); and Legends of the Saxon Saints (1879); and in prose, Essays Chiefly on Poetry (1887); and Essays Chiefly Literary and Ethical (1889). He also wrote a picturesque volume of travel-sketches, and two dramas in verse, Alexander the Great (1874); and St Thomas of Canterbury (1876). According to the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, both of these dramas, "though they contain fine passages, suffer from diffuseness and a lack of dramatic spirit."[9] One of his best remembered poem is Inisfail while two of his historical poems used to be on the Junior Cycle English syllabus,[10] The March to Kinsale[11] and The Ballad of Athlone.[12]

Influences

In his Recollections he says that Byron was his first admiration, but was instantly displaced when Sir Aubrey put Wordsworth's "Laodamia" into his hands. He became a disciple of Wordsworth, whose calm meditative serenity he often echoed with great felicity; and his affection for Greek poetry, truly felt and understood, gave dignity and weight to his own versions of mythological idylls. A critic in the Quarterly Review of 1896 said of his poetry, that next to Browning's it showed the fullest vitality, the largest sphere of ideas, covered the broadest intellectual field since Wordsworth.[7]

- "May Carols and Legends of Saxon Saints" (1857)

- "Legends and Records of the Church and Empire" (1887)

- "Mediæval Records and Sonnets" (1898)

But perhaps he will be chiefly remembered for the impulse which he gave to the study of Celtic legend and Celtic literature. In this direction he has had many followers, who have sometimes assumed the appearance of pioneers; but after Matthew Arnold's fine lecture on Celtic Literature, nothing perhaps did more to help the Celtic revival than Aubrey de Vere's tender insight into the Irish character, and his stirring reproductions of the early Irish epic poetry.[9]

A volume of Selections from his poems was edited in 1894 (New York and London) by G. E. Woodberry.[9]

References

- Gosse, Edmund (1913). "Aubrey de Vere." In: Portraits and Sketches. London: William Heinemann, pp. 117–125.

- Ward, Wilfrid (1904). Aubrey de Vere: A Memoir. London: Longmans, Green and Co., p. 1.

- Ward (1904), p. 4.

- "The De Vere Family by Patrick J. Cronin" (PDF). www.limerickcity.ie.

- "Aubrey Thomas de Vere (1814–1902)", The English Poets, (Thomas Humphry Ward, ed.), Vol. V

- "Aubrey Thomas De Vere" (PDF).

- Smith, Helen Grace. "Aubrey Thomas Hunt de Vere." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 4. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908. 18 March 2016

- "Census of Ireland 1901, De Vere". National Archives of Ireland.

-

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "De Vere, Aubrey Thomas". Encyclopædia Britannica. 8 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 121.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "De Vere, Aubrey Thomas". Encyclopædia Britannica. 8 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 121. - "Intermediate Poetry: a New Anthology Specially Compiled for the Intermediate Certificate Course in Accordance with the Programme of the Department of Education".

- "The March to Kinsale".

- "The Ballad of Athlone".

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Aubrey Thomas Hunt de Vere". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Aubrey Thomas Hunt de Vere". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Aubrey Thomas de Vere. |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Aubrey Thomas de Vere |