Audley End House

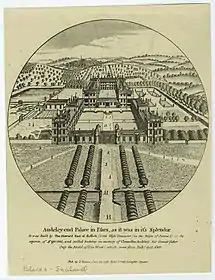

Audley End House (grid reference TL524381) is a largely early 17th-century country house outside Saffron Walden, Essex, England. It is a prodigy house, a palace in all but name and renowned as one of the finest Jacobean houses in England.

| Audley End House | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | Country house |

| Location | Saffron Walden |

| Coordinates | 52°01′15″N 00°13′14″E |

| Area | Essex |

| Built | 17th Century |

| Architectural style(s) | Jacobean |

| Owner | English Heritage |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Official name | Audley End House |

| Designated | 1 November 1972 |

| Reference no. | 1196114 |

| Official name | Audley End |

| Designated | 1 July 1987 |

| Reference no. | 1000312 |

Location of Audley End House in Essex | |

Audley End is now one-third of its original size, but is still large, with much to enjoy in its architectural features and varied collections. The house shares some similarities with Hatfield House, except that it is stone-clad as opposed to brick.[1] It is currently in the stewardship of English Heritage and long remained the family seat of the Barons Braybrooke.[2] Audley End railway station is named after the house.

History

Audley End was the site of Walden Abbey, a Benedictine monastery that was dissolved and granted to the Lord Chancellor Sir Thomas Audley in 1538 by Henry VIII. The abbey was converted to a domestic house for him and was known as Audley Inn.

The house was a key stop during Elizabeth I's Summer Progress of 1578. The progress was to be, like her progresses to Cambridge and Oxford in 1564 and 1566, filled with scholarship, learned debates, and theatrical diversions. Writers and scholars from nearby Cambridge University used the occasion to write papers and speeches. One of these was Gabriel Harvey who by 1578 had been appointed professor of rhetoric at Cambridge. For the Audley End presentations, Harvey had prepared a series of lectures to be delivered to prominent members of the court in attendance with the Queen. Among them was the Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, to whom Harvey wrote:

"For a long time past Phoebus Apollo has cultivated thy mind in the arts. English poetical measures have been sung by thee long enough. Let that courtly epistle—more polished than even the writings of Castiglione himself— witness how greatly thou dost excel in letters. I have seen many Latin verses of thine; yea, even more English verses are extant. Thou hast drunk deep drafts not only of the muses of France and Italy but hast learned the manners of many men, and the arts of foreign countries. It was not for nothing that Sturmius himself was visited by thee. Neither in France, Italy, nor Germany are any such cultivated and polished men.

O thou hero worthy of renown, throw away the insignificant pen, throw away bloodless books and writings that serve no useful purpose. Now must the sword be brought into play. Now is the time for thee to sharpen the spear and to handle the great engines of war. What if suddenly a most powerful enemy [Spain] should invade our borders? If the Turk should be arming his savage hosts against us? What though the terrible war trumpet is even now sounding its blast? Thou wilt see it all. Even at this very moment thou art fiercely longing for the fray. I feel it. Our whole country knows it. In thy breast is noble blood. Courage animates thy brow, Mars lives in thy tongue, Minerva strengthens thy right hand, Bellona reigns in thy body, within thee burns the fire of Mars. Thine eyes flash fire, thy will shakes spears. Who would not swear that Achilles had come to life again?"

The reference to the Earl’s many Latin verses and even more English verses, and that "thy will shakes spears", has been put forward as a piece of evidence in the theory that the Earl was the author of the Shakespeare poetry and plays.

The House was demolished by Thomas Howard, 1st Earl of Suffolk (Lord Howard de Walden[1] and Lord Treasurer), and a much grander mansion was built, primarily for entertaining James I. The layout reflects the processional route of the king and queen, each having their own suite of rooms. It is reputed that Thomas Howard told King James he had spent some £200,000 creating this grand house, and it may be that the king had unwittingly contributed. In 1619, Suffolk and his wife were found guilty of embezzlement and sent to the Tower of London but a huge fine secured their release. Suffolk died in disgrace at Audley End in 1626.

Noted English naval office bureaucrat and diarist Samuel Pepys visited Audley End and described it his diary entry for October 8, 1667. [3] At this time, the house was on the scale of a great royal palace, and became one when Charles II bought it in 1668 for £50,000[2] for use as a home when attending the races at Newmarket. It was returned to the Suffolks in 1701.

Over the next century Sir John Vanbrugh was commissioned to work on the site and parts of the house were gradually demolished[1] until it was reduced to its current size. The main structure has remained little altered since the main front court was demolished in 1708 and the east wing came down in 1753.

Sir John Griffin, fourth Baron Howard de Walden and first Baron Braybrooke, introduced sweeping changes before he died in 1797. In 1762, he commissioned Capability Brown to landscape the parkland, and Robert Adam to design new reception rooms on the house's ground floor in the neoclassical style of the 18th century with a formal grandeur.

Richard Griffin, 3rd Baron Braybrooke, who inherited the house and title in 1825, installed most of the house's huge picture collection, filled the rooms with furnishings, and reinstated something of the original Jacobean feel to the state rooms.

Audley End was offered to the government during the Dunkirk evacuation but the offer was declined due to its lack of facilities.[4] It was requisitioned in March 1941[4] and used as a camp by a small number of units before being turned over to the Special Operations Executive. The SOE used the house as a general holding camp[5] before using it for its Polish branch. Designated Special Training School 43 (STS 43), it was a base for the Cichociemni. A war memorial to the 108 Poles who died in the service stands in the main drive; the Polish SOE War Memorial, unveiled on 20 June 1983, was Grade II listed in 2018.[6]

After the war, the ninth Lord Braybrooke resumed possession, and in 1948 the house was sold to the Ministry of Works, the predecessor of English Heritage.

Gardens and grounds

The Capability Brown parkland includes many of the neo-classical monuments, although some are not in the care of English Heritage. The grounds are divided by the River Granta, which is crossed by several ornate bridges one of which features on the back cover of the BBC Gardeners' World Through the Years book,[7] and a main road which follows the route of a Roman road.

With help from an 1877 garden plan and William Cresswell's journal from 1874,[7] the walled kitchen garden was restored by Garden Organic in 1999 from an overgrown, semi-derelict state. Completed in 2000, it was opened by Prince Charles and features in a book presented to him on his wedding to Camilla Parker Bowles.[8][9] It now looks as it would have done in late Victorian times; full of vegetables, fruits, herbs and flowers which have been supplied to the Dorchester Hotel.[7] It now boasts 120 apple, 60 pear and 40 tomato varieties.[10]

Audley End in 1880

Audley End in 1880 The garden front

The garden front

Paintings

The house contains a number of paintings, many still the property of the Braybrooke family.[11]

Media appearances

The house and grounds have been used in popular television and radio shows, including Flog It!, Antiques Roadshow and Gardeners' Question Time.[12][13][14]

During 2017, scenes were filmed at Audley End for Trust produced by Danny Boyle and based on the life of John Paul Getty III.[15] On 7 September 2018, scenes were shot for The Crown.[16] Previously, interior shots of the Library and Great Hall had been used to portray rooms in Balmoral, Windsor Castle and Eton.[17][18]

Audley End appears in a popular series of videos on English Heritage's YouTube channel featuring the character of Mrs Crocombe, head cook at the house during the 1880s.[19]

References

- Hadfield, J. (1970). The Shell Guide to England. London: Michael Joseph.

- "History of Audley End House and Gardens". English Heritage. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

- https://www.pepysdiary.com/diary/1667/10/08/

- Valentine 2004, pp. 55-56.

- Valentine 2004, p. 66.

- Historic England. "Polish SOE War Memorial (1451516)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 23 December 2018.

- Search, Gay (2003). BBC Gardeners' World Through the years. London: Carlton Books Limited. ISBN 1-84442-416-2.

- "Featured organic vegetable garden". www.gardenadvice.co.uk. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- "Garden book present for Charles". 9 April 2005. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- "Blue Peter - Audley End House and Gardens". Retrieved 12 September 2018.

- {https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/audley-end-house-and-gardens/history-and-stories/collection/ "Collection Highlights"], English Heritage.

- "BBC One - Flog It!, Series 11, Duxford". BBC. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- "BBC One - Antiques Roadshow, Series 39, Audley End 1". BBC. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- "BBC Radio 4 - Gardeners' Question Time, Audley End". BBC. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- "BBC - Trust - Media Centre". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 12 September 2018.

- "TVs Crown at Audley End". Walden Local. 12 September 2018.

- Shahid, S (17 October 2017). "The Crown: We spent the day at filming location Audley End House". Hello Magazine. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- Robinson, Anne (1 December 2017). "THE CROWN: HISTORY'S ROLE IN BRINGING THE MODERN MONARCHY TO LIFE". English Heritage. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=Audley+End+House+and+Gardens&sp=EiG4AQHCARtDaElKeVI4SnBTQ0kyRWNSSFVNWmlGdUIwTXc%253D

- Anon (2006). Oil paintings in public ownership in Essex. London: the Public Catalogue Foundation. ISBN 1-904931-14-6.

- Roger, Turner (1999). Capability Brown and the Eighteenth-century English Landscape (2nd ed.). Chichester: Phillimore. pp. 92–93. ISBN 978-1-86077-114-9.

- Valentine, Ian (2004). Station 43 Audley End House and SOE's Polish Section. Sutton Publishing Ltd. ISBN 0-7509-3708-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Audley End House. |

- Audley End Information at English Heritage

- Friends of Audley End Volunteer group supporting the house

- 'Four centuries of change in a historic country house' on Google Arts & Culture