August Endell

August Endell (1871–1925) was a designer, writer, teacher, and German architect. He was one of the founders of the Jugendstil movement, the German counterpart of Art Nouveau. His first marriage was with Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven.

Life

August Endell was born on April 12, 1871, in Berlin. In 1892 Endell moved to Munich, where he gave up his dream of being a teacher and instead became a scholar. He studied aesthetics, psychology and philosophy, German literature, and art at the University of Munich. He had the intention to pursue a doctorate degree in academics, but changed direction when he met Hermann Obrist, who became a close friend,[1] and whose work was characterized by expressive ornamentation of observed submarine flora and fauna. Although influenced and encouraged by Obrist, Endell was primarily concerned with translating his idea of mobile space into architecture and decorations. Endell expressed important ideas on the stylistic intention underlying the work of Jugendstil artists at the time.[2] In 1898 Endell joined the Initiative of Artistic Münchner Vereinigten Werkstätten für Kunst, and established himself as one of the innovators and leaders of the Kunstgewerbler movement.[3]

In the spring of 1900, Endell met Else Plötz (later the Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven), then an actress and aspiring artist who took private art lessons from him.[4] The couple was married in a civil service on 22 August 1901 in Berlin.[4] They had an open relationship, and in 1902 Else Endell became romantically involved with a friend of Endell’s, the poet and translator Felix Paul Greve (later the Canadian author Frederick Philip Grove). After the trio travelled together to Palermo, Italy, the Endells’ marriage disintegrated[5] and the pair divorced in 1906.[6] Although their separation was acrimonious, and Freytag-Loringhoven dedicated several satirical poems to August Endell,[7] the relationship was influential for both artists. Endell later married sculptor Anna Meyn (1882–1967), with whom he had a child. In 1918 Endell was appointed director of the Breslau Academy of Art, in which function he served until he fell ill and died on 13 April 1925 at the age of 54.

Career

Endell is noted for many designs. In 1897 he received his first commission, an important one that made him practically famous overnight: to design the façade of the Atelier Elvira Photographic Studio in (Munich), which belonged to Hermann Obrist.[2] HIs design included an abstract depiction of a dragon coming out of a wave like element. His use of curve lines implied a sense of calmness to the intricate and massive piece. Organic elements further enforced with the decoration of coral. The building incorporated elements of styles by Antoni Gaudí and Hector Guimard. Unfortunately the Atelier Elvira was burned to the ground during World War II.

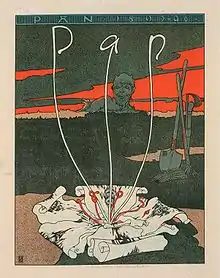

In 1899, August Endell became co editor of the magazine Pan, a literary magazine that was published from 1895 to 1900 in Berlin, Germany.[2] The magazine played a key role in the development of the Art Nouveau movement as a whole, printing illustrations by both well-known and young upcoming artists. . Endell published one of his own essays titled, " Um die Schönheit,” in which Endell comments on how exhibitions of art, stressed from nature is not a set of design ideal for art. Then writing that, “ … we are on the threshold of not only the new style, but also the development of a completely new art. The art of applying forms of nothing insignificant, not representing anything, and not resembling anything… running deep into our souls, so deeply and so strongly as only music can do.[8]” Endell believed that art and style should be the power of direct impact in form on viewer’s personal feelings. His opinions of art and style were highly valued by other artists of the time such as, Franz Stuck, Lovis Corinth, and Ernst Kirchner; being favored highly by futurist artist and expressionists.[8] In his essays, Endell paved the way for abstract art in Germany. Endell’s personal art theory was based on a psychological aesthetic of perception. He believed formal art should be separate from nature. He felt very strongly about art evoking strong feelings through freely invented forms, just as music does through sounds. Endell also contributed illustrations and decorative designs for wall reliefs, carpets, textiles, coverings, window glass and lamps to the publication Pan[2]

Not long after, in 1901, he contributed to the design of the Theater Bunte, in Berlin Germany, which has since been destroyed. Designing all the decorative elements, carpets, fabrics, and even the nails used in the building of the theater. Each area of the theater was painted a different diverse color, thus the name Theatre Bunte, Bunte meaning “colored.[8]”

Endell was also responsible for the design of the Hackesche Höfe, a notable courtyard complex in the centre of Berlin,[9] as well as the design for a sanatorium in Wyk auf Föhr built in 1902. August Endell then went on to design several private homes and villas in the towns of Berlin and Potsdam in Germany.

All while working as a self-taught architect, Endell was continuously publishing articles, essays, and books on his thought of design. In 1908 he published the book The Beauty in the Big City. Within the book the vision of a modern city is developed through Endell’s artistic perspective. He describes the city as taking place at the beginning of the 20th century. He describes the city as a place were work, culture, and art can all be exchanged. A few additional architectural designs August Endell worked on were; 1912 design of the Racecourse Gallop of Mariendorf, 1912 the Trabrennbahn in Berlin Germany, and in 1914 the temporary location of the exhibition of Deutscher Werkbund.

August Endell was a designer and an architect. From there he moved on to the idea of a new visual art and began creating fine art works that were architecturally structured while still expressing the qualities of other forms of art. He began creating and building things such as gates, arches, stairway rails, and other decorative wall elements.

References

- "MOMA". Oxford University Press. Retrieved February 17, 2012.

- Buddensieg 1983 1–389"

- Gammel, Irene. Baroness Elsa: Gender, Dada, and Everyday Modernity. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002, 108.

- Gammel, Baroness Elsa, 109.

- Gammel, Baroness Elsa, 129.

- Gammel, Baroness Elsa, 144.

- Freytag-Loringhoven, Elsa von. Mein Mund ist lüstern / I Got Lusting Palate: Dada Verse. Trans. and Ed. Irene Gammel. Berlin: Ebersback, 2005, 112–118.

- Mahler, Astrid, "A World of Forms from Nature: New Impulses for the Aesthetic of the Jugendstil", Visual Resources: An International Journal of Documentation

- "Hackesche Höfe". Land Berlin. Archived from the original on April 29, 2011. Retrieved May 5, 2011.

Bibliography

- Gammel, Irene. “Munich’s Dionysian Avant-Garde in 1900.” Baroness Elsa: Gender, Dada, and Everyday Modernity. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002. 89–121