Aukh

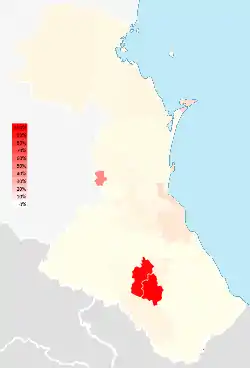

Aukh (Chechen: Ӏовх, Ӏовха, 'Ovkha, Ӏовхойн мохк; Russian: Ау́х) is a historical Chechen region in the current republic of Dagestan. Aukh encompasses parts of the Novolak, Khasavyurtovsky Babayurtovsky and Kazbekovsky districts.[2] The Chechens of Dagestan call themselves Aukhovites, and speak a sub dialect of the Galanchozh dialect.[3]

Historical Inhabitants of Aukh

Aukh was always inhabited by Chechen tribes and were mentioned by several sources of the time as Okoki, Kachkalyki, Gueni, Michkizi and others. The Kumyk General and writer Devlet-Mirza Shikhaliev wrote in 1848 that one of the most ancient inhabitants of Endirey(one of the oldest and biggest settlements in Aukh) were the Gueni who he considered to be Chechen(from the teip Gunoy).[4] Aukh was very mixed with a lot of different Chechen Teips from all areas of Chechnya and Ingushetia, due to this the tribes living there had several different names in Russian sources. All of them recognized themselves as Nakhchoy (Chechens) as can be attested by the letter to the inhabitants of Endirey in 1756 by the Sala-Uzden prince Adzhi who in his letter calls all of the inhabitants "Nation of Nakhshai".[5]

History

Okotsk Lands

(Russian: Окоцкая земля) is an Old Russian term used by the Russian Tsardom to denote a Chechen feudal state, which they encountered in the 16th century.[6] Okotsk was one of the biggest and most influential states in the North Caucasus, and had a rivalry with the other polities of Dagestan, particularly the Kumyk controlled Shamkalate of Tarki.[7] It distinguished itself by being in opposition to Persian, Ottoman and Crimean hegemony over the North Caucasus, allying itself with the Russian Tsardom instead.[8] The Knyaz Shikh Okotsky commanded at some point a host of 500 Cossacks and 500 Chechens (Aukhovites), although the 500 Aukhovites were part of a larger immobilized Chechen force of 1000 infantry and 100 mounted cavalry.[8] In the year 1583 Shikh Murza's joint Chechen-Cossack force would attack an Ottoman force traveling from Derbent to the Sea of Azov to the aid of the Crimean Khanate, the Ottoman force took significant damage which hampered their transit from Derbent to the Sea of Azov.[8]

Aukh Naibstvo

In the 19th century, Aukh was incorporated into the Caucasian Imamate as one of many Chechen Naibstvo's (Administrive unit of the Caucasian Imamate).[9] In 1843 the Aukh Naib district was one of the most important Naibstva, it had up to 1500 families and could equally supply 1500 soldiers to the Caucasian Imamate. In another report from 1857 Aukh under Naib Hatu had in total 530 warriors or which 200 were cavalry and 330 infantry. [10][11] Another famous Naib of Aukh was Bashir-Sheikh from Endirey who belonged to the famous Endirey nobility called Sala-Uzden. Bashir Sheikh was in 1834 considered as a candidate for the leadership of the Imamate but declined due to his injury that made one of his legs lame.[12]

Administrative Dispute

In 1921, Aukh was included in the Dagestan ASSR, despite the desire of Aukhovites to join the Chechen-Ingush Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. According to another explanation, the reason was the entering Aukhovites fear of losing their winter pastures in the territory of the Khasavyurtovsky District. In 1943, the territory was incorporated into the Aukh district, which only lasted til February 1944, when Aukhovite Chechens were ethnically cleansed from their homeland along with the rest of the Chechen nation. Part of Aukh was incorporated into the new Novolaksy district and the property and houses of the ethnically cleansed Chechens, were given to Laks free of charge. The villages Shircha-Aukh (Kalininaul) and Aukh-Aktash (Leninaul) were transferred to the Kazbekovski District and the property there was given to Avars. In 1956, Chechens began to return to their historical homeland, widespread ethnic conflict ensued.

Ethnic cleansing

With the permission of the authorities of the Soviet Dagestan, on October 5, 1943, the Aukhovites formed their national Aukhov district (the territory of the modern Novolaksky and part of the Kazbekovsky regions) with the center in Yaryksu-Aukh (modern Novokuli). But at the end of February 1944, the Aukhovites, sharing a similar fate with other Vainakhs, were ethnically cleansed from their homeland. The authorities disbanded the Aukh district, giving the land of Aukhovites to other ethnic groups of Dagestan.[13]

In the period from 1957 to 1960, the majority of Aukhovites returned to the Soviet Dagestan, however, the leadership of the republic forbade them to resettle the land of their ancestors, especially in the Novolaksky and Kazbekovsky districts (only a few successfully repatriated). Due to restrictions, Aukhovites began to settle in other settlements of the republic, which the authorities indicated to them (legislatively, this ban was enacted by a resolution of the Council of Ministers of the DASSR on July 16, 1958). Until 1961, Aukhovites fought for their return to their native places of residence after which under the threat of a new ethnic cleansing, they had to temporarily abandon their claims.[14]

Aukhovites never abandoned attempts to return their former dwellings occupied by Avars and Laks. The resulting interethnic tension led to clashes, sometimes with tragic consequences. In 1964, Aukhovites made another attempt to return to their native homeland, acting in an organized manner and emphasizing the peaceful nature of their action. The leadership of the Soviet Dagestan was confused and declared these actions “riots”, although no repressive measures were taken against the participants in the events then. Once again, Aukhovites tried to return to their homes in 1976 and 1985 in the village of Chapaevo (Chech. Keshen-Evla), and in 1989 in many native Aukh villages. In response to these actions, the local party leadership began to turn the Avars and Laks against the Aukhovites. On July 3, 1989, a rally was organized demanding the renewed cleansing of Aukhovites from Dagestan.[15]

Chechen villages in Aukh

- Kalininaul (Chech. Ширча-Ӏовх)

- Leninaul (Chech. Акташ-Аух or Пхьарчхошка)

- Endirey (Chech. Ӏаьндари)

- Altimirza-yurt (Chech. Алтимирзи-Юрт)

- Barchkhoy (Chech. Барчха, Barҫxa)

- Bursun (Chech. Буьрсана, Bursana)

- Boni-Aul (Chech. Бони-Эвла)

- Boni-yurt (Chech. Бони-Юрт)

- Bilt-Aul (Chech. Билтой-Эвла, Biltoy-evl)

- Gachalki (Chech. ГӀачалкхие, Ġaҫalkxie)

- Keshen Aukh (Chech. Кешен Аух)

- Mazhgara (Chech. МажгӀара, Maƶġara)

- Minai-Atagi (Chech. Минай-АтагӀа, Minay-ataġa)

- Pkharchkhoski (Chech. Пхьарчхошка, Pharҫxoşka)

- Sala-yurt (Chech. Салой-Юрт, Saloy-yurt)

- Yamansu (Chech. ЙамантӀи, Yamant'i)

- Aukh (village) (Chech. Ӏовхьа)

- Zori-kuotor (Chech. Зори-КӀуотор)

Notable Chechens from Aukh

- Baybulatov, Irbaykhan — senior lieutenant and battalion commander of the Soviet Union during WW2, awarded the title Hero of the Soviet Union posthumously

- Beterbiev, Artur — current unified light-heavyweight boxing champion.

- Nuradilov, Khanpasha — Soviet machine gunner, Hero of the Soviet Union recipient

- Otarsultanov, Dzhamal — Olympic wrestler, won the gold medal in men's freestyle 55 kg at the 2012 London Olympics

- Saitiev, Adam — freestyle wrestler, multiple World and European champion and winner for gold at the 2000 Summer Olympics at 85 kg cat.

- Saitiev, Buvaisar — widely considered the greatest freestyle wrestler of all time,[16] currently a deputy in the State Duma representing Dagestan.

- Saritov, Albert — Olympic wrestler, 2016 Olympics bronze medalist

- Şahin, Ramazan — Olympic wrestler, 2008 Olympics gold medalist

Teips living in Aukh

Aukh is home to many teips, with some of them being native to the area, while others settled there later on. The following is a list of teips that live in Aukh today:[17]

- Akkoy (Chech. Iаккой, 'Akkoy)

- Akxshoy (Chech. Акхшой, Aqşoy)

- Alleroy (Chech. Iаларой, 'Alaroy)

- Barchkhoy (Chech. Барчхой, Barҫxoy)

- Benoy (Chech. Беной)

- Biltoy (Chech. Билтой)

- Bonoy (Chech. Боной)

- Chentiy (Chech. Чӏентий, Ҫ̇entiy)

- Chkharoy (Chech. Чхарой, Ҫxaroy)

- Chontoy (Chech. Чонтой, Ҫontoy)

- Gendargnoy (Chech. Гендаргной)

- Ghordaloy (Chech. ГӀордалой, Ġordaloy)

- Ghuloy (Chech. Гӏулой, Ghuloy)

- Kevoy (Chech. Кевой)

- Khindakhoy (Chech. Хӏиндахой, Hindaxoy)

- Kurchaloy (Chech. Курчалой, Kurҫaloy)

- Merkxoy (Chech. Меркхой)

- Merzhoy (Chech. Мержой)

- Nokqoy (Chech. Ноккхой)

- Ovrshoy (Chech. Овршой, Ovrşoy)

- Pharchakhoy (Chech. Пхьарчахой, Pẋarchaxoy)

- Qovstoy (Chech. Къовстой, Q̇ovstoy)

- Kxarkhoy (Chech. Кхархой, Qarxoy)

- Sherbaloy (Chech. Шербалой, Şerbaloy)

- Shinroy (Chech. Шинрой, Şinroy)

- Shirdiy (Chech. Ширдий, Şirdiy)

- Tarqoy (Chech. Таркхой, Tarqoy)

- Tsechoy (Chech. Цӏечой, Ċeҫoy)

- Tsontaroy (Chech. Цӏоьнтарой, Ċöntaroy)

- Vyappiy (Chech. Ваьппий, Väppiy)

- Zandkhoy (Chech. Зандкъой, Zandq̇oy)

- Zhevoy (Chech. Жевой, Ƶevoy)

- Zogoy (Chech. Зӏогой, Z'ogoy)

Gallery

References

- "АККИ́НЦЫ". bigenc.ru.

- Сигаури, Илесс (1997). Очерки истории и государственного устройства чеченцев с древнейших времён. Русская жизнь. p. 223. ISBN 5-7715-0061-5.

- "Обоснованно ли включение чеченского языка в Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger?". Современная Наука.

- https://e-libra.su/read/532280-rasskaz-kumyka-o-kumykah.html

- Баширов, Саламбек (2018). Этническая история Терско-Сулакского междуречья (на примере семьи Башир-шейха Аксайского). Chechnya, Russian Federation: АО «ИПК «Грозненский рабочий». p. 22. ISBN 978-5-4314-0294-4.

- KUSHEVA, Ekaterina Nikolaevna. (1963). Народы Северного Кавказа и их связи с Россией, вторая половина XVI-30-е годы XVII века. pp. 60, 61. OCLC 561113214.

- Кушева, Екатерина Николаевна (1899-199.). (1997). Русско-чеченские отношения : вторая половина XVI-XVII в : сборник документов. Vostočnaâ literatura. ISBN 5-02-017955-8. OCLC 496144184.

- Айнудинович Адилсултанов, Асрудин (1992). Акки и аккинцы в XVI—XVIII веках. Kniga. ISBN 5766605404.

- Ėnt︠s︡iklopedii︠a︡ kulʹtur narodov I︠U︡ga Rossii. Zhdanov, I︠U︡. A. (I︠U︡riĭ Andreevich), Жданов, Ю. А. (Юрий Андреевич), Severo-Kavkazskiĭ nauchnyĭ t︠s︡entr vyssheĭ shkoly. Rostov-na-Donu: Izd-vo SKNT︠S︡ VSh. 2005. pp. 48–49. ISBN 5-87872-089-2. OCLC 67110999.CS1 maint: others (link)

- http://www.vostlit.info/Texts/Dokumenty/Kavkaz/XIX/1800-1820/Dvizenie/201-220/219.htm

- http://www.vostlit.info/Texts/Dokumenty/Kavkaz/XIX/1840-1860/Karta_Shamil_1273/text.htm

- Баширов, Саламбек (2018). Этническая история Терско-Сулакского междуречья (на примере семьи Башир-шейха Аксайского). Chechnya, Russian Federation: АО «ИПК «Грозненский рабочий». pp. 5–6. ISBN 978-5-4314-0294-4.

- Shnirelʹman, V. A. (Viktor Aleksandrovich); Шнирельман, В. А. (Виктор Александрович) (2006). Bytʹ alanami : intellektualy i politika na Severnom Kavkaze v XX veke. Moskva: Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie. p. 403. ISBN 5-86793-406-3. OCLC 69903474.

- Shnirelʹman, V. A. (Viktor Aleksandrovich); Шнирельман, В. А. (Виктор Александрович) (2006). Bytʹ alanami : intellektualy i politika na Severnom Kavkaze v XX veke. Moskva: Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie. p. 403. ISBN 5-86793-406-3. OCLC 69903474.

- Shnirelʹman, V. A. (Viktor Aleksandrovich); Шнирельман, В. А. (Виктор Александрович) (2006). Bytʹ alanami : intellektualy i politika na Severnom Kavkaze v XX veke. Moskva: Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie. pp. 403, 404. ISBN 5-86793-406-3. OCLC 69903474.

- "Olympics-Russian wrestler Saitiev abandons comeback attempt". Reuters.

- Шнайдер, Алексис. "ЧЕЧЕНСКИЕ ТЕЙПЫ И ТУКХУМЫ".