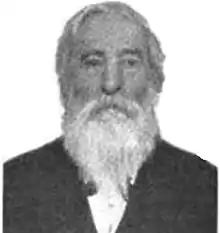

Austin Cornelius Dunham

Austin Cornelius Dunham (June 10, 1833 – March 17, 1918) was an American businessman, executive, merchandiser, inventor and philanthropist. He was the manager, director, or trustee in several firms and organizations. He was involved with the textile industry and manufactured yarns and clothing.

Austin Cornelius Dunham | |

|---|---|

circa 1898 | |

| Born | 10 June 1833 |

| Died | 17 March 1918 (aged 84) |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Yale University |

| Occupation | businessman |

| Known for | electrical |

| Parent(s) | Austin Dunham Marttha Matilda Root |

| Notes | |

1 sister and 4 brothers | |

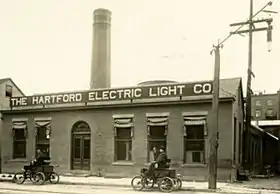

Dunham was a promoter of state-of-the-art technology in the electrical industry. In one way or another he was involved with methods of transmission of electrical energy, arc lighting systems, rotary converters, electrical current regulators, and central distribution equipment. As chief executive officer of Hartford Electric Light Company for over thirty years he managed the distribution of electricity throughout the state of Connecticut.

Early life

Dunham was born in the town of Coventry, Connecticut, on June 10, 1833.[1] His parents were Austin Dunham and Martha (Née Root) Dunham. He was given the nickname Cornelius. He moved with his family to Hartford, Connecticut in 1835. Dunham's father was a merchant and businessman in Hartford. He was in the business of manufacturing cotton as well as a banking and insurance executive, which enterprises Dunham took over later after his father's death. Dunham's maternal grandfather was Judge Jesse Root.[2]

Dunham attended primary school in Hartford, and North Coventry. He went to high school in Ellington, Connecticut. He graduated from there in 1850 when seventeen and immediately entered Yale University, graduating in 1854 at the age of twenty-one.[3] His first job after that was as a teacher in Elmira, New York, for a year. In 1856 he returned to the city of Hartford and was involved with manufacturing and merchandising.[1]

Career

Dunham was also an organizer of the Austin Organ Company and the Automatic Refrigeration Company.[2] He was an administrator of the Aetna Fire Insurance Company, Travelers Life Insurance Company, Connecticut National Exchange Bank, and the Cedar Hill Cemetery. Dunham was also an agent of the Watkinson Juvenile Asylum and Farm School, the Watkinson Public Library, and the Hartford Grammar level school. He was president of Rock Manufacturing Company, Dunham Hosiery Cooperative and Hartford Electric Company.[1] Dunham was a member of Austin Dunham and Company and E. N. Kellogg and Company. He was also a business affiliate of the enterprise Austin Dunham's Sons, maker of worsted yarns and chief executive officer of Dunham Hosiery Company maker of all-wool hosiery.[4]

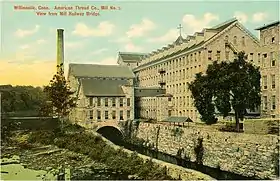

Dunham was a partner of the Willimantic Linen textile business when it was created in 1854.[5] He eventually became vice-president of the company in 1877 when his father, company founder, died.[6] The main building for the Willimantic Linen textile business in the nineteenth century was the company store and top floor called the Dunham Hall was a classroom where the workers learned English and also served as Willimantic's first public library. A new mill was constructed in 1880 to replace the old multi-story mill.[7]

Dunham was an acquaintance of Thomas Edison and because of this the Willimantic Linen textile business in 1880 became the first such concern to be illuminated by electricity. It used arc lights at first and later was replaced with a safer incandescent light bulb system.[8] The electrical power came from the Willimantic River ("fast-flowing water") which dam for a power plant was at Mohegan, Connecticut. The factory was the only one floor mill constructed and at the time the largest textile mill worldide. Dunham experimented at this mill with a storage battery and pondered the idea of producing hydroelectric power 24 hours a day and storing the electricity in batteries during the slow use times for using during high production times. With his company general manager and vice president William Elliot Barrows they did electrical experimentation at this mill. One item they built was a 300-ton lead-acid battery bank that produced 400-kilowatt of power that was equipped to store surplus electricity to use during peak production times.[6][9]

Hartford Electric Light Company

Dunham acquired Hartford Electric Light Company (HELCO) in 1883 as a concern that was going out of business and developed it into a large power utility enterprise.[2] He was chief executive officer of the electric firm for over thirty years.[10] Dunham was a pioneer in electrical application developments through his company from knowledge he acquired from electrical experimentation he had done in the previous four years with Barrows at Willimantic textile business.[7][10] Under his direction HELCO was the first utility cooperative in the nation to transmit a three-phase electric current for a distance of several miles.[11][12] Dunham was a leader to successfully connect commercial electric alternators in parallel, the first to use a storage battery in connection with a hydroelectric power plant to regulate power and the first to use aluminum commercially in a transmission conductor.[11]

HELCO under the direction of Dunham was a leader in introducing modern methods of transmission of energy from water power, the first to use enclosed arc lamps, the 60-cycle rotary converters, and the constant-current alternating arc-light system. He led the way to the adoption of the steam turbo-generator as a part of regular central-station equipment. Dunham also launched the Nernst lamp into commercial use.[10] He had HELCO make and market by 1908 the Dunham electric range he invented that was a broiler, cooker, and roaster.[9]

Later life and retirement

Dunham became interested in farming using trucks and promoted that in his retirement. He bought the Corbin farm in Newington, Connecticut, and established some five-acre tracts. There he built houses and barns using concrete as the main construction material.[2] He divided the land into five acre plots to be given to eligible families that would promise to work the farm at least an hour before sunrise and at least an hour after sunset a day and devote to productive farming. Each farmhouse was equipped with all modern conveniences of the time including running water. The barn was stocked with the necessary tools and seeds to run the farm. The farm included forty hens in each chicken-coop. Each farming family got a pig and a cow to start. They were to work at a normal city job during the daytime.[13] When the United States entered into World War I he gave control of the farm land management to the Storrs Agricultural School.[2]

Dunham became interested in many charities in his retirement. His main one was the Hartford Hospital. Another was the Sheffield Scientific School at Yale College and their Electrical Engineering Laboratory. He was a director of the Cedar Hill Cemetery and president of the Hartford Hospital.[2] Dunham made several trips to Florida and Cuba during his retirement.[2] He died at St. Petersburg, Florida, on March 17, 1918.[2]

Works

"Reminiscences of Austin C Dunham" – autobiographical papers published as a serial in the Hartford Courant newspaper 1912–1913.[2]

Family

Dunham married Lucy J. Root on September 16, 1858.[2] Lucy died in September 1864 when she was 23.[14] Lucy was Dunham's cousin, since she was the granddaughter of Jesse Root's oldest son, Ephraim.[14] Dunham and his wife had two children; an elder son named George, who died in 1873 when he was 13 years old, and a younger daughter named Laura. She was a student at the Yale School of Art during 1876–77 and married Danford Newton Barney on March 22, 1890.[2]

References

- Charles H. Leeds (1896). "Austin Cornelius Dunham". Record and Statistics: 43–44. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

- "Austin Cornelius Dunham". Obituary records of Yale University graduates. 20 (8): 549–551. 1919. Retrieved September 13, 2015.

- "Electrical Engineering at Yale". Yale Sheffield monthly. 20 (8): 367. 1914. Retrieved September 13, 2015.

- Herndon 1898, p. 311.

- Peter Metzke (2013). "Willimantic Cotton Mills, Co". Gary N. Mock. Archived from the original on September 27, 2015. Retrieved September 13, 2015.

- Tom Beardsley (2021). "The Bright Lights of Willimantic". Connecticut Explored. Retrieved January 30, 2021.

- "Mill museum saves Willimantic's hard history". The Boston Globe. Boston, Massachusetts. April 13, 2008. p. 148 – via Newspapers.com

.

. - Danilov 2005, p. 134.

- "Austin Cornelius Dunham". We Relate. 2021. Retrieved January 30, 2021.

- John McGhie (1896). "Long Distance Transmission of Power Electricity in the United States". Electrical World. 71: 639. Retrieved January 13, 2021.

- Kane 1997, p. 219.

- "25 Things You Might Not Know About Hartford". Hartford Courant newspaper. Oct 26, 2014. Archived from the original on 2015-09-25. Retrieved September 13, 2015.

- "5-Acre Farms for Nothing". The Brooklyn Citizen. Brooklyn, New York. May 10, 1913. p. 8 – via Newspapers.com

.

. - Messier 1987, p. 164.

Bibliography

- Danilov, Victor J. (2005). Women and Museums. AltaMira Press. ISBN 9780759108554.

- Herndon, Richard (1898). Men of Progress. New England Magazine. OCLC 14572908.

- Kane, Joseph Nathan (1997). Famous First Facts, Fifth Edition. The H. W. Wilson Company. ISBN 0-8242-0930-3.

- Messier, Betty Brook (1987). The Roots of Coventry, Connecticut. 275th Anniversary Committee. OCLC 747334198.