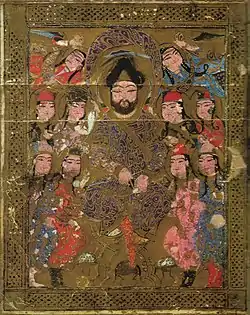

Badr al-Din Lu'lu'

Badr al-Din Lu'lu' (Arabic: بدر الدين لؤلؤ) (died 1259) (the name Lu'Lu' means 'The Pearl', indicative of his servile origins) was successor to the Zengid emirs of Mosul, where he governed in variety of capacities from 1234-1259 following the death of Nasir ad-Din Mahmud. He was the first mamluk to transcend servitude and become an emir in his own right, anticipating the rise of the Bahri Mamluks to the sultanate of Egypt by twenty years. He preserved control of al-Jazira through a series of tactical submissions to larger neighboring powers, at various times recognizing Ayyubid, Seljuqs of Rûm, and the Mongol overlords. His surrender to the Mongols spared Mosul the destruction experienced by other settlements in Mesopotamia.

Rise to power

Lu'lu' was an Armenian convert to Islam,[1] and a freed slave in the household of the Zangid ruler Nur al-Din Arslan Shah I. Recognized for his abilities as an administrator, he rose to the rank of atabeg and, after 1211, was appointed as atabeg for the successive child-rulers of Mosul, Nur al-Din Arslan Shah II and his younger brother, Nasir al-Din Mahmud. Both rulers were grandsons of Gökböri, Emir of Erbil, and this probably accounts for the animosity between him and Lu'lu'. In 1226 Gökböri, in alliance with al-Muazzam of Damascus, attacked Mosul. As a result of this military pressure, Lu'lu' was forced to make a submission to al-Muazzam. Nasir al-Din Mahmud was the last Zengid ruler of Mosul, he disappears from the records soon after Gökböri's death. He was killed by Lu'lu', by strangulation or starvation, and his killer then formally began to rule in Mosul in his own right.[2][3]

Ruler of Mosul

In 1234 Lu'lu' minted the first coins in his own name. Following his usurpation his new position as ruler of Mosul was recognised by the Abbasid Khalif, Al-Mustansir, who bestowed upon him the praise name al-Malik al-Rahim (The Merciful King). During his reign he sided with successive Ayyubid rulers in his disputes with other local princes. In 1237 Lu'Lu' was defeated in battle by the army of the Khwarazmshah and his camp was thoroughly looted. Lu'lu' was in conflict with Yezidi Kurds in his territories, he ordered the execution of one Yezidi leader, Hasan ibn Adi, and 200 of his followers in 1254. He died shortly after the definitive invasion of Mesopotamia by the Mongols.[4][5]

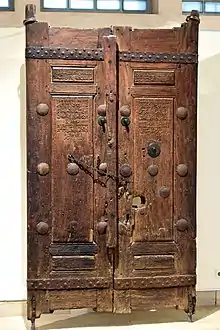

Lu'lu' built extensively in his domain, improving the fortifications of Mosul, the Sinjar Gate bearing his device survived into the 20th century, and constructing religious structures and caravanserais. He built the shrines of Imam Yahya (1239) and Awn al-Din (1248). The ruins of his palace complex, known as the Qara Saray (1233-1259), were visible until the 1980s.[6]

Family

- Isma'il ibn Lu'lu', the son of Badr al-Din Lu'lu, ruled Mosul for only three years (1259 - 1262) before his city was lost to the Mongols.[7]

- A daughter of Lu'lu' was set to marry Aybak, as his second wife after Shajar al-Durr. However, Aybak was killed before the marriage could take place.

References

- Islamic art and architecture 650-1250 By Richard Ettinghausen, Oleg Grabar, Marilyn Jenkins , pg, 134

- Gibb, pp. 700-701

- Patton, pp.152-155

- Kreyenbreoek and Rashow, p. 4

- Bloom and Blair (eds.), pp. 249, 499

- Bloom and Blair (eds.), p. 249

- Spengler and Sayles, p. 140

Bibliography

- Bloom, J.M. and Blair, S.S. (eds.) (2009) The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture, Volume I: Abarquh to Dawlat Qatar, Oxford University Press, Oxford

- Gibb, H.A.R. (1962) "The Aiyubids", in History of the Crusades, Volume 2: The Later Crusades, 1189-1311, Wolff, R.L. and Hazzard, H.W. (eds.), Ch. XX, pp. 693–714, University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia PA.

- Kreyenbroek, P.G. and Rashow, K.J. (2005) God and Sheik Adi are Perfect, Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden

- Patton, D. (1988) Ibn al-Sāʿi's Account of the Last of the Zangids, Zeitschrift der Deutschen, Morgenländischen Gesellschaft, Vol. 138, No. 1, pp. 148-158, Harrassowitz Verlag Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43377738

- Spengler, W.F. and Sayles, W.G. (1992) Turkoman Figural Bronze Coins and Their Iconography: The Artuquids, Clio's Cabinet, Lodi

External links

- Imam Awn al-Din Mashhad (Mosul)

- Imam Yahya ibn al-Qasim Mashhad (Mosul)

- Sittna Zaynab Mausoleum (Sinjar)