Barnacle goose myth

A myth about barnacle ( Branta "anas" leucopsis) and brant (Branta bernicla) geese is that these geese emerge fully-formed from goose barnacles] (Cirripedia).[1] There are doubts as to the origin of the myth, which can be connected to the medieval Bestiary or to an earlier pre-Christian period.[2] The myth owes its popularity to an ignorance of the migration patterns of geese and of birds in general. Early medieval discussions of the nature of living organisms were often based on myths or a genuine ignorance of what is now known about phenomena such as bird migration. It was not until the late 19th century that research showed that such geese migrate northwards to nest and breed in Greenland or northern Scandinavia.[3][4]

One of the earliest references to the myth of the barnacle goose is in The Exeter Book of Riddles.[5] The riddle is asked as follows:

“ …..My beak was close fettered, the currents of ocean, running cold beneath me.

There I grew in the sea, my body close to the moving wood.

I was all alive when I came from the water clad all in black, but a part of me white.

When living the air lifted me up, the wind from the wave bore me afar - up over the seal’s bath…..

Tell me my name...."

To which the anticipated answer was: The Barnacle Goose. [6]

13th century – Gerald of Wales

Gerald of Wales[7] provided the basis for the dissemination of the myth before being referenced by medieval bestiaries. He may have been the first to record in Latin folk tales or myths about spontaneous generation or transformation of young barnacle geese from rotten wood via the goose-necked barnacle (Cirripedia) to fledgling geese. In 1177 the future English king John (the younger brother of Richard the Lionheart) was appointed Lord of Ireland and the English rule was set in these territories. As a royal clerk and chaplain to King Henry II of England, Gerald of Wales accompanied Prince John between 1183 and 1186 on an expedition to Ireland. After his return, in 1187 or 1188, he had published a manuscript with the description of the new Irish lands called Topographia Hibernica.

His views on Ireland in Topographia Hibernica [8] include the following passage:

“ … there are many birds called barnacles (bernacae) … nature produces them in a marvellous way for they are born at first in gum-like form from fir-wood adrift in the sea. Then they cling by their beaks like sea-wood, sticking to wood, enclosed in a shell-fish shells for freer development…. thus in the process of time dressed in a firm clothing of feathers, they either fall into the waters or fly off into freedom of the air. They receive food and increase from a woody and watery juice…… on many occasions I have seen them with my own eyes, more than a thousand of these tiny little bodies, hanging from a piece of wood on the sea-shore when enclosed in their shells and fully formed. Eggs are not produced from the copulation of these birds as is usual, no bird ever incubates an egg for their production … in no corner of the earth have they been seen to give themselves up (to) lust or build a nest ….”[9]

The Middle Ages – England

In the 12th and 13th centuries, scholars such as Gervase of Tilbury and Alexander Neckam frequently referred to myths or folklore about the natural world. Both Gervase and Neckam repeated earlier stories about the origin of the goose. Neckam wrote of a bird called the "bernekke".[10][11]

The Middle Ages – Scotland and Pope Pius II

In 1435, Aeneas Silvius Bartholomeus (later Pope Pius II)[12] travelled to Scotland to encourage James I of Scotland to assist the French in the Hundred Years War. He spent several months travelling around Britain, and recorded these travels in his book entitled "de Europa". A short section of the book is devoted to Scotland and Ireland. He described James as “… a sickly man weighed down by a fat paunch ...”. He noted the cold inhospitable climate of Scotland and “ .. semi-naked paupers who were begging outside churches (and) went away happily after receiving stones as alms…”. [13]

Continuing in this vein, he records the following story:

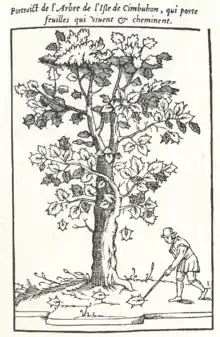

" …I / We… heard that in Scotland there was once a tree growing on the bank of a river which produced fruits shaped like ducks.[14] [15] "When these were nearly ripe, they dropped down of their own accord, some onto the earth, and some into the water. Those that landed on the earth rotted away, but those that sank into the water instantly came to life, swam out from below the water, and immediately flew into the air, equipped with feathers and wings. When I eagerly investigated this matter, I learned that miracles always recede further into the distance and that the famous tree was to be found not in Scotland but in the Orkney islands…"

It is believed that this story from Pope Pius II is the first recorded account of the Barnacle Geese myth in Scotland. [16]

The 16th century and Hector Boece

Some 75 years after Pope Pius II, Hector Boece in his "Scotorum Historiae a Prima Gentis Origine"[17] gave further credence to this story with an account of a discussion he had with his friend and colleague Canon Alexander Galloway[18] on an island called Thule.[19] The event, if it occurred, would have to have been sometime between c.1506-1520. Boece allows Galloway in the narrative to give two contrasting accounts of the geese story. Boece records:[20]

" …. It remains for me (Boece) to discuss those geese commonly called clacks, (claiks) [21] which are commonly but wrongly imagined to be born on trees in these islands, on the basis of what I have learned from my diligent investigation of this thing. ….. I will not hesitate to describe something I myself witnessed seven years ago… Alexander Galloway, parson of Kinkell, who, besides being a man of outstanding probity, is possessed of an unmatched zeal for studying wonders… When he was pulling up some driftwood and saw that seashells were clinging to it from one end to the other, he was surprised by the unusual nature of the thing, and, out of a zeal to understand it, opened them up, whereupon he was more amazed than ever, for within them he discovered, not sea creatures, but rather birds, of a size similar to the shells that contained them …. small shells contained birds of a proportionately small size….. So, he quickly ran to me, whom he knew to be gripped with a great curiosity for investigating suchlike matters and revealed the entire thing to me…..”

The Claik or Clack Geese, sometimes clag-geese,[22] as they were known to Boece, survived scrutiny during the Scottish Enlightenment. The age of the myth and the lack of empirical evidence on bird migration led to other erroneous accounts of the origins of barnacle geese being common until the 20th century. [23]

20th century

As noted, many of the accounts of the myth can be traced back to Hector Boece and from there back to The Exeter Book of Riddles. In the 20th century the most detailed account of the nature of this myth and its interpretation can be found in a paper by Alistair Stewart (1988)[24] As noted above, there are a variety of accounts from Boece: some perpetuated by Thomas Dempster (1829)[25] In this 20th century telling, Stewart quotes John Bellenden's Scots vernacular speech.[26] In this Bellenden had Boece write:

“…. because the 'rude' and 'ignorant' people saw oft-times the fruits hat fell off the trees which stood near the sea converted within (a) short time in(to) geese, they believed that these geese grew upon the trees hanging by their 'nebs', just as apples and other fruits hang by their stalks. But their opinion is not to be sustained for, as soon as these apples and fruits fall from the tree in(to) the sea-flood they grow first worm-eaten, and 'by short process of time', are altered in(to) geese....”.

So allowing Stewart to conclude:

“…. Bellenden's Boece (gave) a fresh lease of life to the tale; …(recently)… naturalists ha(ve) located the barnacle geese nurseries in Greenland and ha(ve) a rough idea of the migration routes….But parallel to scientific advances the old versions continued to have a folklife existence....”

The myth in Jewish thought

Almost all of the references in published literature follow a tradition exemplified by Stewart[27] and Müller[28] with regard to where the myth may have emerged. In The Jewish Encyclopaedia, the entry for “Barnacle-Goose” suggests a strong Jewish connection in addition to a largely western Christian tradition. The source is referred to in a volume of manuscripts collected by Solomon Joachim Halberstam in c. 1890, the Ḳehillat Shelomoh. [29] The question of slaughtering Barnacle Geese is referenced to Isaac ben Abba Mari of Marseilles (יצחק בן אבא מרי ) (c.1120–c.1190) in around c.1170. Such a date is a century before Gerald of Wales. Further, the Jewish Encyclopaedia extends the non-Western source to c. 1000 in a work by Al-Biruni, that is Abu Rayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni (CE 973–1048).

See Also

References

- Minogue, Kristen (29 January 2013). "Science, Superstition and the Goose Barnacle". Smithsonian Environmental Research Center. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- Sprouse, S. J. (2015). The Associative Branches of the Irish Barnacle: Gerald of Wales and the Natural World. Hortulus, 11, 2.

- Kenicer, G. J. (2020). Plant Magic, Edinburgh, Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh; pp 150-151.

- Mayntz, M. (2020). Migration: Exploring the Remarkable Journeys of Birds. London: Quadrille; pp 110-111; the following article provides a comprehensive historical account of the Barnacle Goose Myth, Lappo, E. G., Popovkina, A B & Mooij, J H. (2019). About geese growing on trees The Medieval interpretation of the Barnacle and Brent goose origin. Goose Bulletin, 24(July), 8-21; retrieved from https://cms.geese.org/sites/default/files/Goose%20Bulletin24.pdf (25th January 2021). Not all the sources referenced are available in English.

- Details from the following: Tupper, F. (1910). The Riddles of the Exeter book. Boston Mass. ; London,; Tupper, F. (1906). Solutions of the Exeter Book of Riddles. Modern Languages Notes, 21(4), 97-105.; Tupper, F. (1903). The comparatives Study of Riddles. Modern Language Notes, XVIII(1), 1-8.

- SOPER, H. (2017): Reading the Exeter Book Riddles as Life-Writing. The Review of English Studies, New Series, Vol. 68 (287): 841-865. Doi: 10.1093/res/hgx009; BAUM, P.F. (1963): Anglo-Saxon Riddles of the Exeter Book. – Duke Univ. Press, Durham, North Carolina, USA. In addition see, Anglo-Saxon Riddles of the Exeter Book Cathedral Library MS 3501. See, https://www.exeter-cathedral.org.uk/history-heritage/cathedral-treasures/exeter-book/

- Also known in Latin as Girandus Cambrensis, and Gerald de Barri or Gerald of Wales, c. 1146–1223)

- in Topographia Hibernica - See below for sources.

- There are many versions of Gerald of Wales' account of Ireland Topographia Hibernica. For an authoritative account of the versions see, Sargent, A. L. B. (2011). Visions and Revisions:Gerald of Wales, Authorship and the construction…in 12th & 13th Century Britain. (PhD). University of California, Berkeley. A popular account of the variety of sources can be found in, Bartlett, R. (1979). Gerald of Wales (1146-1223): University of Oxford., pp 114-117 and p 222. An older source, Giraldus, C., & Wright, T. (1913). The historical works of Giraldus Cambrensis. London: G. Bell and Sons Ltd. is also valuable. The Associative Branches of the Irish Barnacle: Gerald of Wales and the Natural World. Hortulus, 11, 2. (https://hortulus-journal.com/sprouse/#f1) In total there are more than thirty relevant 12th century MSS. A recent article by Stewart, Stewart, A. M. (1988). Hector Boece and ‘claik’ geese. Northern Scotland, 8 (First Series)(1), 1723. doi:10.3366/nor.1988.0003 can be relied on within the context of Hector Boece and the “claik” geese or barnacle geese myth; also, Bartlett, R. (1979). Gerald of Wales (1146-1223): University of Oxford, provides a comprehensive biography of Gerald along with textual details of the Barnacle Goose myth.

- Oman, C. C. (1944). The English Folklore of Gervase of Tilbury. Folklore, 55(1), 2-15. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1257623 (31 January 2021)

- Neckam, A. (1863). Alexandri Neckam de Naturis Rerum libri duo, with a poem of the same author, De Laudibus Divinae Sapientiae, Longman, Green, Longman, Ch XLVIII, p. 99 "Ex lignis abiegnis salo diuturno tempore madefactis originem sumit avis quae vulgo dicitur bernekke" ("From fir wood soaked for a long time there arises the origin of the bird commonly called the bernekke.)

- Enea Silvio Bartolomeo Piccolomini (1405-1464). He wrote two books, “Florence A. Gragg, and Leona C. Gabel. 1988. Secret memoirs of a Renaissance Pope : the commentaries of Aeneas Sylvius Piccolomini, Pius II : an abridgement (Folio Society: London) and, “Piccolomini, Aeneas Silvius, Robert Brown, Nancy Bisaha, and ProQuest (Firm). "Europe (c. 1400-1458)”

- Pope Pius probably saw the gift of coal to beggars and Bedesmen. Bedesmen were often given coal or peat to heat the rooms in their Hospital accommodation.

- There are differences in the original sources for this story. In some the Latin "aves" - "bird" is used; in others it is "Anetarum" derived from "anatum" - "duck"', coming from "anas/anatis"; in others, "anserum" - "goose"

- see also, http://mdz-nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb10159158-6 - fol.55v, line 5

- See the following sources for details of the story told by Pope Pius II in "de Europa" and "Commentaries". Pius, Florence A. Gragg, and Leona C. Gabel. 1988. Secret memoirs of a Renaissance Pope : the commentaries of Aeneas Sylvius Piccolomini, Pius II : an abridgement (Folio Society: London); Piccolomini, Aeneas Silvius, Robert Brown, Nancy Bisaha, and ProQuest (Firm). "Europe (c. 1400-1458)." - at - http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/abdn/detail.action?docID=3135080; and, "Cosmographia, 1509, (Paris)". The book by Nancy Bisaha and Robert Brown " Europe (c. 1400-1458) contains an extensive bibliography.? The biography of Pope Pius II, Ady, Cecilia M. 1913. Pius II (Aeneas Silvius Piccolomini) : the Humanist Pope (Methuen: London). contains a Bibliography and an account of the Barnacle Geese story - p. 44.

- Boece, H. and G. Ferrerio (1574). Scotorum historiae a prima gentis origine ... libri XIX. Parisiis, Du Puys. The earliest version of this work about the history of Scotland dates from 1527.

- Galloway was an eminent scholar and canon priest in St Machar's Cathedral in Old Aberdeen. He is best remembered as a liturgist, master of works and academic to Bishops of Aberdeen from Elphinstone to Gordon.

- Thule appears to be imaginary. Different views on its location place it north of Scotland and beyond the Orkney isles. Olaus Magnus on his Carta Marina identifies the location, calling it Tile.

- There are a number of editions of Boece's History of Scotland. John Bellenden and Raphael Holinshead provide the basis many editions. The 1575 edition by John Ferrier is used for reference in this entry. A modern translation from the Latin is provided by Dana Sutton http://www.philological.bham.ac.uk/boece/ is also used. Two sources are recommended for the "Claik Geese" story: Alasdair M. Stewart, 'Hector Boece and "Claik" Geese', Northern Scotland, 8 (First Series) (1988); and, Edward Heron Allen, Barnacles in Nature and in Myth (London,1928). NB: The Mar Lodge edition of Historia does not contain the story of the geese. This volume is now in the Morgan Library and Museum, New York. A recent edition of Boece's story about the Barnacle Geese can be found in, Dana F. Sutton, Hector Boethius, - Scotorum Historia (1575 version) http://www.philological.bham.ac.uk/boece/, 2010), Ch. 33 & 34. The text above is a translation from Alasdair M. Stewart (1988), pp. 17-23.

- The term “clackis” is sometimes used in the north of Ireland . See, Payne-Gallowey, Ralph Sir. The Fowler in Ireland, or, Notes on the Haunts and Habits of Wildfowl and Seafowl : Including Instructions in the Art of Shooting and Capturing Them. Southampton: Ashford, 1985, p 23; also barnacle may be called “bernicle” in Ireland, pp. 158-159.

- Barnacle geese are known in Scots language as "claik geese". "Claik" is the Scots word for a barnacle. See "Claik goose n. comb.". Dictionary of the Scots Language. 2004. Scottish Language Dictionaries Ltd. <http://www.dsl.ac.uk/entry/snd/claik_goose>, [Accessed 1 Nov 2017]; The OED gives a wider variety of explanation including the sound made by Barnacle Geese (Anas leucopsis) "claik, n." OED Online, Oxford University Press, June 2017

- A 20th century antiquarian and librarian , P J Anderson, referring to Boece and Galloway, comments on the credulity of the conversation reported by Boece, as follows “… (Galloway )…. is said to have studied the antiquities of the Hebrides, and to have written upon the subject of the clag-geese, those mythical birds whom mediaeval credulity believed to grow on trees. …. The goose inquiry may be condoned as an inspiration of juvenile credulity!...”. From, Anderson, P. J. (1906). Studies in the history and development of the University of Aberdeen : a quatercentenary tribute paid by certain of her professors and of her devoted sons. Aberdeen, Aberdeen University Press. p.103.

- Stewart, Alasdair M. "Hector Boece and ‘Claik’ Geese." Northern Scotland 8 (First Series), no. 1 (1988): 17-23. https://doi.org/10.3366/nor.1988.0003.; http://www.euppublishing.com/doi/abs/10.3366/nor.1988.0003.

- Dempster, Thomas, David Irving, and Bannatyne Club (Edinburgh Scotland). Thomae Dempsteri Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Scotorum : Sive, De Scriptoribus Scotis. Bannatyne Club Publications. Editio altera ed. 2 vols. Edinburgi: Excudebat Andreas Balfour cum sociis, 1829. http://digital.nls.uk/101200539.

- Boece, Hector, and John Bellenden. The Hystory and Croniklis of Scotland. Edinburgh: Davidson, 1536.

- Stewart, Alasdair M. "Hector Boece and ‘Claik’ Geese." Northern Scotland 8 (First Series), no. 1 (1988):

- Müller, F. Max. Lectures on the Science of Language, London, 1880.

- in, The Jewish Encyclopaedia, v7, 166-167.