Baroness Mary Vetsera

Marie Alexandrine Freiin von Vetsera (19 March 1871 – 30 January 1889) was a member of Austrian "second society" (new nobility) and one of Crown Prince Rudolf of Austria's mistresses. Vetsera and Rudolf were found dead by apparent suicide, at his hunting lodge, Mayerling in January 1889, an event known as the Mayerling incident.

Mary Freiin von Vetsera | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Marie Alexandrine Freiin von Vetsera 19 March 1871 |

| Died | 30 January 1889 (aged 17) Mayerling, Lower Austria, Austria-Hungary |

| Title | Freiin von Vetsera |

| Partner(s) | Rudolf, Crown Prince of Austria |

| Parent(s) | Albin Freiherr von Vetsera Hélène Baltazzi |

_%E2%80%93_Gerd_Hru%C5%A1ka.png.webp)

Early life

Known by the English form of her name, Mary (her maternal grandfather's second wife was English), she was the youngest child of Albin von Vetsera, a diplomat in foreign service at the Austrian court,[1] and his much younger wife, Hélène (also known as Eleni) Baltazzi, a member of a wealthy Greek noble family from the island of Chios, then part of the Ottoman Empire.[2][3] Albin, who was made a baron in 1870 by the Emperor Franz Joseph, was 22 years older than his young and socially ambitious wife.[4][5] Mary had three siblings: Johanna (known as Hannah), Ladislaus, and Franz Albin. Both of Hélène's sisters had married counts and Mary and her sister were expected to raise the family's social status by continuing the tradition of marrying into families of importance.[6]

Mary von Vetsera attended a finishing school for nobility. These exclusive boarding schools, for girls of noble birth between the ages of 12 and 17, were geared to a moral education, not an academic one, which was thought to give a young woman "intellectual pretensions". Those institutes emphasized social graces: French, music, drawing, dancing, and handicrafts, preparing young women for their roles in society as aristocratic wives and mothers.

"Smart Society", made up of parvenu elements, who were considered to lack pedigree but wealthy, now began to command more attention from the leaders in more aristocratic circles of the beau monde.[7] The Vetsera family occupied this niche, and Hélène von Vetsera held lavish parties in attempts to socialize with the upper echelons of the Austrian court, all in order to introduce her daughter to the most eligible men. Famous for "her elegance and taste in dress",[8] she acquired the nickname "The Turf Angel" for her love of horserace meets at the Freudenau course.[9] It was very apparent to the Imperial family, that Vetsera was being blatantly groomed by her mother for an advantageous marriage; Empress Elisabeth noted in 1877: "Madame Vetsera wants to come to Court and gain recognition for her family."[1] Countess Larisch von Moennich, a niece of the Empress and one of Vetsera's closest friends, claimed she had confided: "Mamma has no love for me.... Ever since I was a little girl she has treated me like something she means to dispose of to the best advantage."[10]

Relationship with Crown Prince Rudolf of Austria

Mary von Vetsera met Crown Prince Rudolf in November 1888 and they began a three-month-long affair. Other accounts, however, describe their relationship as one of three years' duration, which would have made Vetsera about 15 when they met.

[At Ambassador Reuss's reception in late January 1889] Rudolph noticed me and leaving Stéphanie came straight up to me. "She is there," he said without any preamble, "ah, if somebody would only deliver me from her!" "She" was Mary Vetsera, his mistress of the ardent face. I, too, glanced at the seductress. Two brilliant eyes met mine. One word will describe her. Mary was an imperial sultana, one who feared no other favourite, so sure was she of the power of her full and triumphant beauty, her deep black eyes, her cameo-like profile, her throat of a goddess, and her arresting sensual grace. She had altogether taken possession of Rudolph, and she longed for him to be able to marry her. Their liaison had lasted for three years...At the soirée I was struck by my brother-in-law's state of nervous exhaustion but I thought it well to try and calm him by saying a word or two about Mary which would please him, so I remarked quite simply: "She is very beautiful"...Rudolph left me without replying. An instant later he returned and murmured: "I simply cannot tear myself away from her."

— Louise of Coburg, My Own Affairs, 1921, p.120

Given her mother's ambitions for her and the fact that Rudolf was married to Princess Stephanie of Belgium, her family and friends found this liaison foolish and potentially socially compromising for the family as well. When Hélène discovered that Vetsera had sent Rudolf a personally engraved cigarette case, she said: "She is compromising herself when she is scarcely 17 years old and so is ruining not only her life but also that of her brothers and sisters and mother..."[11]

Maureen Allen, an American friend of Vetsera, recalled that she did not take this affair or any of her earlier ones frivolously, that she "was very serious...people gave her credit for not taking love lightly, but rather quite seriously."[11] While Rudolf had not only a wife and child, but other lovers as well, Vetsera did not pursue any other eligible men, but instead focused all her attention on the crown prince. She appears to have thought she could be a credible threat to Princess Stephanie, perhaps even usurping her position and title,[12] but seems to have been unaware that Rudolf was simultaneously having a serious affair with the actress Mizzi Kaspar.[13]

Rudolf is reported to have proposed a similar suicide pact to the 24-year-old Kaspar a month before his death at Mayerling, which she rejected, presuming it to be a joke.[14] Vetsera may have been Rudolf's second choice in his search for a partner in death, but it appears she did not interpret his proposal as a notion of a desperate man not wanting to die alone. Her family and friends took pains to emphasize that the emperor and the Vatican would never countenance the dissolution of Rudolf's marriage, and Vetsera no doubt realized that at some point she would have to fulfill her obligation to her family and marry someone who was Rudolf's inferior. She wrote: "If I could give him my life I should be glad to do it, for what does life mean for me?”[15]

One of his secretaries is quite emphatic that while Vetsera, whom he saw as a "somewhat superficial and emotional maid"[16] who, while displaying "a vivacity and sparkle that would have done justice to a very bright Frenchwoman",[8] was "a woman without serious thought"[16] and was not the type of woman who usually appealed to the intellectually inclined Rudolf, although he acknowledged that Rudolf was interested in the political opinions of his other lovers to the extent that they were known to be reflections of what their male relatives thought.[17] Rudolf's close friend, Professor Udel, further explained his master's "strange choice". He said that Vetsera shared a certain "mystic temperament" with the archduke, who could be "the most mystical of men" in that he displayed a "strong vein of superstition".[8]

Death

Vetsera and Crown Prince Rudolf of Austria were found dead in an apparent murder suicide at his hunting lodge.

A common statement ... has it that the Prince was shot through the heart and from behind, a view which would coincide with the first statement – namely, that the body had been found lying on the right side. The same tradition holds that Mademoiselle Vetsera was shot through the left temple – a view entirely coinciding with the assumption that the window to the left of the couch had been opened, and the sleepers murdered. Dr. Widerhofer was admitted at once to the chamber of the Archduke, where the body was already laid out, that of Mademoiselle Vetsera having been removed to an adjoining room, where it was disposed on a couch and completely hidden with a plain white coverlet, pending the arrival of relatives, who had at once been summoned. ... Although I entered the girl's death-chamber, I was prevented, from the position of the table, which ran lengthwise with the couch, from closely observing the body."[18]

Aftermath

.jpg.webp)

Without a judicial inquiry, Vetsera's uncles were summoned to remove their niece's body from Mayerling as secretly as possible and to bury it just as discreetly. Her mother was forbidden to attend. One account posits that this was accomplished that night, with the body of their niece sitting in the carriage between them, propped up by a broomstick pushed up the back of her dress. Vetsera's body was taken to a cemetery at the Cistercian monastery a few miles away in Heiligenkreuz, but because her death was thought to be a suicide, her uncles had to persuade the abbot to give his permission for a Christian burial on the grounds that she had committed suicide because of a temporary loss of her senses. It was only later that the official version of the story surfaced, affirming that Rudolf had shot Vetsera and then himself.

On 16 May 1889, Vetsera's mother had her daughter's grave opened and her remains reburied a few yards away in a more permanent site. The wooden coffin was replaced by a copper one, and a simple monument was erected by the family.

The official story of murder-suicide was unchallenged until just after the Second World War. In 1946, occupying Soviet troops, perhaps hoping to loot the jewels and other valuable items they presumed were interred within, dislodged the granite plate covering the grave and broke into Vetsera's coffin. This was not discovered until 1955, when the Red Army withdrew from Austria. When the fathers of the monastery repaired the grave, they saw a small skeleton inside the damaged copper coffin. They observed the skull, which seemed to have no bullet holes in it.

In 1959, a young physician named Gerd Holler, who was stationed in the area, accompanied by a member of the Vetsera family as well as specialists in funereal preservation, inspected her remains. The bones were in total disarray, but Vetsera's shoes and a quantity of long black hair were found in the coffin. Holler carefully examined the skull and other bones for traces of a bullet hole, but stated that he found no such wound. The skull cavity did show an area of trauma, which could have been inflicted by grave robbers, but also potentially indicated that Vetsera had died from a blow to her skull. This would support the theory that she was not murdered by the Crown Prince.

Holler claimed he petitioned the Holy See to inspect their 1889 archives of the incident, including records of the investigation of the affair by the Papal Nuncio, Archbishop Luigi Galimberti, who had found that only one bullet was fired. Lacking forensic evidence of a second bullet, Holler advanced the theory that Vetsera died accidentally, probably as the result of an abortion, and that Rudolf then shot himself.[19] Holler witnessed the body's re-interment in a new coffin in 1959.

In 1991, Vetsera's remains were disturbed again, this time by Helmut Flatzelsteiner, a Linz furniture dealer who was obsessed with the Mayerling affair. It was initially reported that her bones were strewn round the churchyard for the authorities to retrieve, but Flatzelsteiner actually removed them at night for a private forensic examination at his expense, which finally took place in February 1993.[20] Flatzelsteiner told the examiners that the remains were those of a relative killed some one hundred years earlier who may have been shot in the head or stabbed. One expert thought that this might be possible, but since the skull was in a state of advanced decomposition, it could not be confirmed.

When Flatzelsteiner approached a journalist at the Kronen Zeitung to sell both the story and Vetsera's skeleton, the police became involved. Flatzelsteiner confessed and surrendered Vetsera's remains, which were sent to the Legal Medical Institute in Vienna for further examination. Forensic experts found the bones were indeed a hundred years old and those of a young woman around twenty, but since part of the skull was missing, it could not be determined if there had ever been a bullet hole present or not.[21] Vetsera's bones were re-interred on the morning of 28 October 1993, under the supervision of Abbot Gerhard Hradil.[21] After a court case, Flatzelsteiner paid the abbey some €2,000 by way of restitution for damages to the grave.[22]

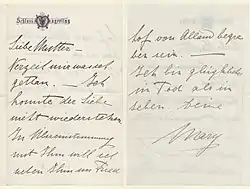

In his book Crime at Mayerling, The Life and Death of Mary Vetsera, Georg Markus claims that what happened at Mayerling was never seriously investigated, and the few investigations that were made were manipulated by the Imperial monarchy. However, on 31 July 2015 the Austrian National Library issued copies of Vetsera's letters of farewell to her mother and other family members. These letters, previously believed lost or destroyed, were found in a safe deposit box in an Austrian bank, where they had been deposited in 1926. The letters, written in Mayerling shortly before the deaths, state clearly and unambiguously that Vetsera was preparing to die alongside Rudolf, out of love for him. They were made available to scholars and exhibited to the public in 2016.[23]

References

- Markus, George, Crime at Mayerling: The Life and Death of Mary Vetsera, Ariadne Press, 1995, p. 23.

- Constantinople, Philip Mansel, Penguin Books Ltd, 1997, ISBN 978-0140262469

- A woman of Vienna, Joachim von Kürenberg, Cassell, 1955, ASIN B001882BM8

- The Androom Archives: Baltazzi, Alexander, Christopher Aidan Long

- Baron Albin Vetsera

- Tosoni, Peter, The Mayerling Tragedy: How and Why did Prince Rudolf and Mary Vetsera Die?, The Durham University Journal 84, no. 2, 1992, p. 204.

- Grant, Hamil, ed., The Last Days of Archduke Rudolph, Dodd, Mead & Co, 1916, p. 114

- Grant, Hamil, ed., The Last Days of Archduke Rudolph, Dodd, Mead & Co, 1916, p. 111

- Morton, Frederick, A Nervous Splendor, Penguin Press, 1980

- Larisch, Marie, My Past, p. 241.

- Markus, George, Crime at Mayerling: The Life and Death of Mary Vetsera: With New Expert Opinions Following the Desecration of Her Grave, Ariadne Press, 1995, p. 30.

- Larisch, Marie, My Past, p. 237: "[T]hat stupid Crown Princess knows I am her rival."

- Serge Schmemann "Mayerling Journal; Lurid Truth and Lurid Legend: A Hapsburg Tale" in New York Times dated 10 March 1989 online at nytimes.com, Retrieved 10 April 2009: "According to Mrs Hamann's research, Prince Rudolf had in fact contemplated suicide for at least a half year before his death. He initially asked the first love of his life, one Mitzi Kaspar, to share his fate, but the 24-year-old woman declined. By contrast, 17-year-old Mary Vetsera, the dark and pudgy daughter of an Hungarian-Armenian baron (Vecsera), was madly in love and willing to do anything for Rudolf. So on Jan. 29, 1889, he took her to his favorite hunting lodge, and the next morning shot her and himself in their bedroom"

- Morton, Frederick, A Nervous Splendour, Penguin Press, 1980, p. 219

- Markus, Georg, Crime at Mayerling: The Life and Death of Mary Vetsera: With New Expert Opinions Following the Desecration of Her Grave, Ariadne Press, 1995, p. 28

- Grant, Hamil, ed., The Last Days of Archduke Rudolph, Dodd, Mead & Co, 1916, p. 110

- Grant, Hamil, ed., The Last Days of Archduke Rudolph, Dodd, Mead & Co, 1916, p. 112

- Grant, Hamil, ed., The Last Days of Archduke Rudolph, Dodd, Mead & Co, 1916, p. 280

- Holler, Gerd, Mayerling: Die Loesung des Ratsels [Mayerling: The Solution to the Riddle], Molden, 1983

- Pannell, Robert, Murder at Mayerling?, in History Today, Volume 58, No. 11, November 2008, p. 67.

- Markus, Georg, Crime at Mayerling: The Life and Death of Mary Vetsera: With New Expert Opinions Following the Desecration of Her Grave, Ariadne Press, 1995

- "Leichnam von Mary Vetsera gestohlen – oesterreich.ORF.at". ktnv1.orf.at. Retrieved 19 May 2018.

- Press release Archived 31 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine from the Austrian National Library, 31 July 2015 (German)

- Additional sources

- Ridley, Chelsea (15 May 2011). "Mayerling Revisited: The Short Life and Death of Mary Vetsera" (pdf). Constructing the Past. Illinois Wesleyan University. 12 (1). Article 6.

External links

Media related to Baroness Mary Vetsera at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Baroness Mary Vetsera at Wikimedia Commons- The Vetsera Collection

- Eulogy on Crown Prince Rudolf of Austria-Hungary