Baths of Titus

The Baths of Titus or Thermae Titi were public baths (Thermae) built in 81 AD at Rome, by Roman emperor Titus.[1] The baths sat at the base of the Esquiline Hill, an area of parkland and luxury estates which had been taken over by Nero (AD 54–68) for his Golden House or Domus Aurea. Titus' baths were built in haste, possibly by converting an existing or partly built bathing complex belonging to the reviled Domus Aurea.[2] They were not particularly extensive, and the much larger Baths of Trajan were built immediately adjacent to them at the start of the next century.[3]

.jpg.webp)

Description

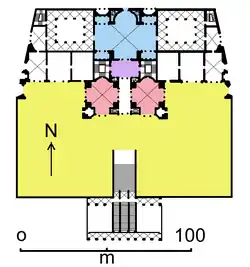

The Baths of Titus were the first of the "imperial" baths to use what would become a standard design for public bathing complexes in Rome in the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD.[4] The entire building was strictly symmetrical, and featured along its center axis from north to south the main bath chambers in a sequence: frigidarium, tepidarium, and caldarium.[5] As in the other thermae, the caldarium was south facing and projected forward from the main block to absorb the warmth of the sun to best effect.[6] Preceding the building on the south side was a terrace supporting a large open area, presumably featuring gardens, which was another typical feature of the later Roman imperial baths.[7] The only major feature not present in the Baths of Titus is a natatio, or open air swimming pool, which in the later baths of Trajan, Caracalla, and Diocletian preceded the frigidarium on the north side.[8]

The frigidarium was the largest room, consisting of three bays with groin vaulted ceilings and enclosures in each corner supporting barrel vaults. These enclosures were screened by columns and contained cold plunge baths.[9] Flanking the frigidarium on the east and west sides was a palaestra for exercise and apodyteria, or changing rooms.[10] The small intermediate room, the tepidarium, was flanked by staircases on either side leading to an upper story; from the south ran a corridor separating a pair of large caldaria. According to the floorplans of Andrea Palladio, each caldarium had a small laconicum (dry sweating room) attached to it.[7] Smaller suites of hot rooms ran along the south façade on either side of the tepidarium staircases.

A broad staircase descended 18 meters (59 feet) from the terrace in front of the Baths of Titus down the south side of the Oppian to the plaza of the Colosseum, where it joined with a portico.[11] The ruins of this portico were excavated in 1895; the brick-faced concrete piers can still be seen on the north side of the Piazza del Colosseo.[12][13]

Later history

The Baths of Titus were restored during the reign of Hadrian as well as in AD 238 but no further repairs are known.[14][15] It is thus likely that the entire complex underwent a process of early abandonment. Rodolfo Lanciani determined that the front part of the baths had collapsed by the late 4th century, and offices for the urban prefect were built on the site.[16] Large parts of the building were still standing in the 16th century when Andrea Palladio described the floor plan. The ruins were demolished shortly afterwards, their marble and building materials being reused for the building of palaces and churches such as the side chapels of the Church of the Gesù or the fountain of the Cortile del Belvedere in the Vatican.

One of the features of the baths was mural designs by the artist Famulus (or Fabullus), both al fresco and al stucco. Before the designs fell into disrepair from exposure to the elements, Nicholas Ponce copied and reproduced them as engravings in his volume "Description des bains de Titus" (Paris, 1786). The designs are now recognized as a source of the style known as "grotesque" (meaning "like a small cave, a hollow, a grotto") because the ruins of the Baths of Titus were in a hollow in the ground when they were discovered.[17]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Baths of Titus. |

- Suet. Titus 7 http://latin.packhum.org/loc/1348/1/0#229

- Frank Sear (1983). Roman Architecture. Cornell University Press. pp. 145–. ISBN 0-8014-9245-9.

- American Architect and Architecture. J. R. Osgood & Company. 1900. pp. 27–.

- Sear, 1983; p. 40

- J.B. Ward-Perkins (1994). Roman Imperial Architecture. Yale University Press. p. 73.

- Sear, 1983; p. 40

- L. Richardson (1992). A New Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 396.

- Sear, 1983; p. 145

- Ward-Perkins, 1994; p. 73

- Sear, 1983; p. 145

- Samuel Ball Platner & Thomas Ashby (1929). A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome. Oxford University Press. p. 533-534.

- Ward-Perkins, 1994; p. 73

- "Thermae Titi". exhibits.stanford.edu. Retrieved 2020-11-25.

- Hist. Aug. Max. et Balb. I

- CIL 6.9797

- Rodolfo Lanciani (1897). The Ruins and Excavations of Ancient Rome. Houghton Mifflin. p. 364.

- Lecture 12 - The Creation of an Icon: The Colosseum and Contemporary Architecture in Rome as author at YALE HSAR 252 - Roman Architecture with Professor Diana E. E. Kleiner.