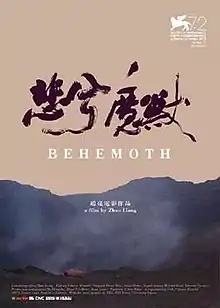

Behemoth (2015 film)

Behemoth (Chinese: 悲兮魔兽; pinyin: bēixī móshòu) is a Chinese documentary film directed by Zhao Liang about the environmental, sociological, and public health effects of coal-mining in China and Inner Mongolia. Loosely based on Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy, Liang’s documentary has been lauded for its surreal cinematography and poignant imagery. The film was released in competition on September 11, 2015 at the 72nd Venice International Film Festival.[2] Regarding the ban in China, the director explained that "even though environmental protection is a national policy, but the regional government quite disliked this type of film (虽然环保是国家政策,但是地方政府对这种电影很反感)".[3] This was not Liang’s first banned film, as his 2009 documentary Petition was also subjected to government censorship.

| Behemoth | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Zhao Liang |

| Produced by | Sylvie Blum |

| Screenplay by | Zhao Liang, Sylvie Blum |

| Music by | Huzi, Alain Mahé |

| Cinematography | Zhao Liang |

| Edited by | Fabrice Rouaud |

| Distributed by | Upside Distribution, Grasshopper Film |

Release date |

|

Running time | 91 minutes[1] |

| Country | China |

| Language | Mandarin |

Plot

Starting with an explosion on the desolate field in Inner Mongolia, Behemoth depicts a hellish large-scale landscape as a result from mining industry. Accompanied by the traditional Tuvan throat singing, the naked back lies in the scene of smoky mountain under the control of “Behemoth”. The man carrying a mirror reflecting the past looks at the desolate mining field, which used to be their beautiful home.

Trucks run all the time in the field transporting raw coal to coke-making factories. Workers, soaked in black smoke and struck by wind, continuously take turns to mine. Their skin, due to long-term exposure to ore and sand, is pocked with red spots and black dust particles.

Shifting from natural mining to industrial smelting, the camera moves to where the pollution is even more severe. But workers continue to endure the extreme working conditions and work day and night. As pointed out in the film, wealth accumulates elsewhere, but all living creatures who once inhabited the space have dispersed and the workers now living there are trapped in poverty. What’s left are the continuous explosions, smelting, atmosphere pollution, smog, and wasted water.

Living in the long-term pollution, the workers’ health is threatened. Besides the smoke-lined eyes and covered skin on the surface, lung cancers developed within them. They cough, have difficulty breathing, and are on the verge of death. Immigrant workers seek help from the government, but their passive hard-working lives are destined to end in nearby graveyards.

Sheep no longer roam there, replaced by statues in memory of the past herding lifestyle. All mining and smelting activities produce steel, which seems to be the building block of desire of a kind of paradise – the modern city.

But the “paradise” is more like a castle in the air with few people actually living inside. Those who dedicated themselves to the production of steel, and the building of the massive uninhabited ghost cities, end up themselves only with death.

The film concludes by inferring that workers and their activities are like the underlings of Behemoth, which itself is created by human beings for the desire for an illusory modern life that escapes the very people working to make it possible. The consequences of such pollution are vast, which leaves many considerations for the viewers.

Production

Created with a limited cast and crew, Behemoth is an example of the burgeoning wave of independent documentaries and films made with limited support and funding.[4] Without the restrictions of a larger production company, these film-makers are able to express more politically scathing ideas without having to cater to the general box-office audience.

Zhao Liang’s documentary only loosely follows the idea of what a movie should be, and instead expresses itself as a form of visual poetry. Limited dialogue, backing score, and an abandonment of conventional cinematic techniques underscores the larger political message of Behemoth.

The cinematography is strongly symbolic and contains myriad allusions to Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy, adopting both its character archetypes and general plot structure. The narrator, a representation of Dante, follows a stand-in for Virgil, who carries a mirror on his back – reflecting the eye of the viewer back on themselves.

The documentary is composed of three chapters, demarcated by a color transition and a general tonal shift. The film starts in the strip mine, Liang’s stand-in for the Inferno or Hell, which is identified with the color red. As the film progresses, the countryside surrounding the pit mines and the lives of its inhabitants is portrayed through a blue transition as Purgatory. The film ends in a satirically mordant Paradise, the culmination of the coal-miner’s labor which supposedly validates their suffering, an uninhabited ghost city represented with the color grey.

Reception

The documentary has been banned in China for its critique of the coal-mining industry and Chinese government, but did receive critical approval in countries across the world.[5]

Selections

- 72nd Mostra Internazionale d’Arte Cinematografica della Biennale di Venezia (in competition), Italy

- Tetrio Millennio Film Fest – Roma Italy

- Viennale - Austria

- CPH: DOX - Denmark

- IDFA Amsterdam - Netherlands

- Traces de Vies – Festival du film documentaire Clermont Ferrand / Vic Le Comte - France

- Stockholm International Film Festival - Sweden

- Tokyo Filmex - Japan

- Porto/Post/Doc Film et Media Festival - Portugal

- WATCH DOCS Human Rights in Film IFF Warsaw - Poland

- Dubai International Film Festival - United Arab Emirates

Awards

- Mostra Internazionale d’Arte Cinematografica Venezia Italie, Green Drop Award, Prix Signis

- Stockholm International Film Festival Suède, Best Documentary

- TOKYO FILMeX Japon, Special Jury Prize

- Porto/Post/Doc Film et Media Festival Portugal, Great Prize Porto/Post/Doc, Teenage Prize

- WATCH DOCS Human Rights in Film IFF Varsaw Pologne, Watch Docs Award for the best film in competition (ex aequo)

- The 40th Hong Kong International Film Festival, Firebird Award of Documentary Competition

Public health relevance

Coal-mining industries involve pollution, but what really matters are the scale and methods of exploitation. In order to rationally utilize natural resources, the scale of exploitation should be determined according to actual adequate needs from the market. (In the film, overproduction is the case.) Thus, there should be a well-considered balance between nature preservation and resource exploitation in the beginning. Methods include the employment of both machines and workers. In terms of machine mining, a better covering and transporting techniques should have been adopted to minimize the effect of smoke and air pollution. In terms of workers’ working conditions, their protections are far less than what is needed.[6]

When it comes to smelting, better waste processing is required. Due to the long-term exposure to dust, smoke, and harmful gases, the probability for workers to get lung cancers rises rapidly.[7]

Atmospheric pollution affects everyone living under the sky, especially those living in the neighborhood, so its sources should be monitored and regulated.[8] In the film, there is a petition for the government to provide help for the suffering workers. However, the effectiveness of execution remains doubtful as depicted later in the film, in that the man carrying the mirror continues to step towards the predictable end of the whole-cycle mining activities.

References

- "'Behemoth' ('Beixi moshuo'): Venice Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- "72nd Venice International Film Festival".

- "中國禁片《悲兮魔獸》蒙城上映 導演詳解被禁原因". Archived from the original on 8 August 2017.

- Brody, Richard. "Independent Filmmaking in China: The Age of Dissent".

- Zhao, Liang. "Behemoth". Zhao Liang Studio.

- Hatton, Celia. "Under the Dome: The smog film taking China by storm".

- Jones, J. "In Zhao Liang's ecological documentary Behemoth, we're the monster".

- "专访柴静". Sohu Website. Renmin Website.

External links

- Frames of Representation: Behemoth (Bei xi mo shou) Q&A on YouTube

- 'Behemoth' Q&A – Zhao Liang – New Directors/New Films 2016 on YouTube

- Behemoth at IMDb

- Film Review: 'Behemoth' on Variety

- As China Hungers for Coal, ‘Behemoth’ Studies the Ravages at the Source, The New York Times

- Short Take: Behemoth, Film Comment