Ben Wilson (basketball)

Benjamin Wilson Jr. (March 18, 1967 – November 21, 1984) was an American high school basketball player from Chicago, Illinois.[1] Wilson, a Neal F. Simeon Vocational High School basketball player was regarded as the top high school player in the U.S. by scouts and coaches attending the 1984 Athletes For Better Education basketball camp. Wilson is noted as the first Chicago athlete to receive this honor. On November 21, 1984, Wilson died due to injuries he sustained in a shooting the day before.[2][3][4][5][6]

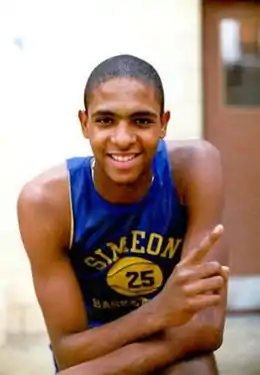

Wilson, 1984. | |

| Personal information | |

|---|---|

| Born | March 18, 1967 Chicago, Illinois |

| Died | November 21, 1984 (aged 17) Chicago, Illinois |

| Nationality | American |

| Listed height | 6 ft 8 in (2.03 m) |

| Listed weight | 190 lb (86 kg) |

| Career information | |

| High school | Simeon (Chicago, Illinois) |

| Position | Guard / Forward |

| Number | 25 |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

Early life

Born in 1967 to Ben Wilson Sr. and Mary Wilson (née Gunter), Wilson was raised in the Chatham neighborhood on Chicago's South Side.[7] Mary Wilson had two sons from a previous marriage, including Curtis Glenn, and would have sons Anthony and Jeffrey with the elder Wilson before the couple divorced.[8] Wilson began playing basketball in elementary school. He started at St. Dorothy School and transferred to Ruggles Elementary School, graduating in 1981. Wilson practiced at Cole Park[9] in Chatham and participated in summer league games in Chicago.[10] As his game developed, friends and family surrounding Wilson began to notice that his talent could make him one of the best players in the sport. They made it a point to protect Wilson from trouble as he got older; as he was entering high school, the nationwide crack epidemic was in full swing and some of the people closest to Wilson, including his older brother Curtis, became addicted. Chicago's violent crime rate was very high during this time as well, especially on the South Side.

High school career

In the fall of 1981, Wilson began his freshman year at Simeon.[11] During the 1982–83 season, he was the only sophomore on the varsity basketball team. For the 1983–84 season, Simeon advanced to the Illinois AA State Championship, which was held at Assembly Hall on the campus of the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. Behind Wilson, Simeon defeated West Aurora High School by nine points in the semifinals and beat top-ranked Evanston Township High School to win their first ever state title.[12] ESPN HS regarded Wilson as the best junior in the country for the 1983–84 season.[13][14] He would play basketball with R. Kelly[15] and Nick Anderson.[16] Wilson was described as "Magic Johnson with a jump shot" by his Simeon coach, Bob Hambric.[17]

Athletes For Better Education (AFBE)

In July 1984, Wilson attended the invitation-only Athletes For Better Education camp in Princeton, New Jersey.[15] The camp allowed scouts and coaches to watch top high school students in a single location. After the week-long event, Wilson was ranked the number-one high school player in America.[15] As his senior season approached, it was believed that Wilson was considering scholarship offers from the University of Illinois, DePaul University and Indiana University.[17]

Death

Background

On November 20, 1984, Wilson decided against lunching with teammates as he wanted to talk to his girlfriend, Jetun Rush, with whom he had been having significant issues. The couple had conceived a child early in 1984, a son named Brandon, and Rush would neither speak to Wilson nor let him see his child. Meanwhile, Calumet High School student Billy Moore was outside Simeon's campus with a pistol looking to avenge his cousin, who had been allegedly robbed of $10 by a Simeon student. After finding out the conflict had been resolved, Moore and his friend Omar Dixon decided to stay nearby and eventually the two followed Moore's friend Erica Murphy to a nearby luncheonette located on South Vincennes Avenue, just up the street from Simeon.

The shooting

Billy Moore, in the ESPN documentary about Ben Wilson, described what happened next.[18] He and Omar Dixon were outside the luncheonette when Wilson and Rush came up the street behind them. Rush was trying to break away from Wilson, who in his desperation to speak to her failed to pay attention to where he was going and bumped into Moore. Moore called to Wilson to watch where he was going, which only served to make the already upset basketball star even more angry as he turned back and approached Moore. The two exchanged words and expletives and Moore revealed the pistol he had been carrying, a .22 caliber revolver.

Seeing Moore's pistol, Wilson taunted him and dared him to shoot. Moore later said he felt that the much larger Wilson was just "punking" him and drew his weapon. Wilson then lunged at Moore, who responded by firing two shots at him. The first struck Wilson in his groin while the second struck him in his abdomen and caused significant internal bleeding.[19] Moore and Dixon then fled. Within minutes, word of the shooting reached Simeon's campus, and a crowd gathered near Wilson. Emergency services were called at 12:37 PM local time, while Simeon basketball coach Bob Hambric made a call to WMAQ-TV newsman Warner Saunders and informed him of what happened.

Paramedics were slow in reaching the scene and at approximately 1:20 PM, Hambric decided to take it upon himself to get his star player to the hospital. Just as he was getting into his car, an ambulance arrived to the scene on South Vincennes. According to Chicago's then emergency protocol, Wilson was taken to the nearest available hospital, which was St. Bernard Hospital in Englewood. St. Bernard was a small community hospital that was not equipped to handle emergencies or trauma cases like shootings, so a call was put out for any available trauma surgeon to report immediately to St. Bernard.

Aftermath

At Simeon, the basketball team remained sequestered in the teachers' lounge for the rest of the day. Wilson's teammate Teri Sampson recalls that throughout the night, the reports progressively worsened, going from Wilson possibly recovering in time for the state playoffs, to perhaps missing a year of play, to possibly never playing again, to fighting for his life.

Wilson's brother Curtis Glenn recounted in the ESPN documentary seeing his brother being wheeled by him in the hospital and noticing his feet were unnaturally pale. Upon examination it was discovered that Wilson's aorta was damaged by the second shot and there was no blood reaching his lower extremities. Despite doctors repeatedly telling her they could save her son, Mary Wilson's professional experience as a nurse told her that even if they were able to repair the damage, Ben would likely be in a persistent vegetative state afterward due to the massive blood he had already lost. Early the next morning, Mary Wilson asked that her son be taken off of life support, and Ben Wilson died shortly thereafter.[12][20]

Soon after the shooting, Erica Murphy returned to her home to find Billy Moore sitting in her living room watching television. It was through this that he discovered who he had shot. Moore remained there until the police began pounding on Murphy's door looking for him later that evening. Dixon's arrest followed, with the charges upgraded to murder once word of Wilson's death reached the police. Police presented both suspects with a case theory that after Moore's conflict with Wilson, Dixon tried to pick Wilson's pockets, and then urged Moore to shoot Wilson. Both young men signed confessions to that effect that were later recanted. Despite being underage at the time, the Cook County District Attorney's office elected to try both men as adults.

At their trial, the prosecutors presented the same case theory to the jury when the trial began the following year. Jetun Rush was the prosecution's lead witness and testified to the same effect. Moore and Dixon's attorneys chose to present Wilson's celebrity as the primary reason for the charges against the two teenagers. Both Moore and Dixon were convicted on charges of murder and attempted armed robbery. Per the recommendations of the prosecuting attorneys, they both were given significant prison sentences. Moore received a forty-year sentence while Dixon received a thirty-year sentence. Dixon was given the lesser sentence because even though he was involved in the crime, Moore had been the one to fire the fatal shots.[21]

The Wilson family's lawsuit against the hospital for inappropriate delay of medical care[22] was settled in 1992 for an undisclosed amount.[23] Dixon was released on parole in 2000, and Moore in 2005. Dixon later began an unrelated sentence for armed robbery, although Moore, interviewed in Benji, claims that his own confession was coerced, and that Dixon was not involved in Wilson's shooting. Wilson died on the same day that Simeon was to open its season. The team chose to play the game, a rematch with Evanston, and won.

Personal life

He had one son, Brandon Wilson (b. September 1984),[24] with his high school girlfriend Jetun Rush. Brandon, who was 10 weeks old when his father died, went on to play basketball at the University of Maryland-Eastern Shore, wearing Wilson's number 25.[25][26]

Legacy

Wilson's friend and Simeon teammate, former NBA and University of Illinois basketball player Nick Anderson, wore jersey number 25 during his career in Wilson's honor.[27] Juwan Howard wore 25 at the University of Michigan as a tribute to Wilson.[27] Former Chicago Bulls guard Derrick Rose, who graduated from Simeon in 2007, wore number 25, and the team won the state championship in 2006 and 2007.[27] He also wore number 25 with the New York Knicks, after being traded. Simeon basketball player Jabari Parker had the number 25 stitched into the team sneakers during his time at Simeon.[28] Following Nick Anderson's tribute to Wilson in wearing number 25 at Illinois, many others who graduated from Simeon and moved on to play for the Illini have carried on the tradition of wearing the jersey number 25. In the years since his murder in 1984, Deon Thomas, Bryant Notree, Calvin Brock, and Kendrick Nunn have all worn 25 during their basketball career at Illinois to honor Wilson.[29] ESPN premiered a documentary on Wilson titled Benji on October 23, 2012.

References

- Hale, Mike (October 22, 2012). "A Rising Star, Extinguished, in 1980s Chicago". The New York Times. Retrieved December 26, 2012.

- Jackson, Scoop (November 21, 2009). "Original Old School: Nuthin' But Love". Slam. Retrieved October 26, 2012.

- Jackson, Scoop (October 23, 2012). "Benji Wilson's ongoing journey". ESPN. Retrieved December 26, 2012.

- Chicken Soup for the Soul: Inside Basketball: 101 Great Hoop Stories from ..., By Jack Canfield, Mark Victor Hansen, Pat Williams.Retrieved December 27, 2019.

- The Great Book of Chicago Sports Lists, By Dan McNeil, Ed Sherman.Retrieved December 27, 2019.

- Derrick Rose, By Adam Woog.Retrieved December 27, 2019.

- Crawford, Bryan (October 24, 2012). "Life of "Benji" Comes Full Circle in Chicago". NBC Chicago. Retrieved December 26, 2012.

- Weingarten, Paul (September 8, 1985). "For love of Ben". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 9, 2016.

- "Nat King Cole Park". Nat King Cole Park. Chicago Park District. Archived from the original on October 10, 2017. Retrieved October 9, 2017.

- "Ben Wilson: A Dream Unfulfilled". ChicagoNow. October 13, 2012. Retrieved December 26, 2012.

- H. A. Bell, Taylor (October 1, 2004). Sweet Charlie, Dike, Cazzie, and Bobby Joe : high school basketball in Illinois (Paper back ed.). Champaign, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-252-07199-7. Retrieved October 8, 2017.

- "Ben Wilson: A Life Cut Short but the Memories Remain". The History Rat. August 19, 2012. Retrieved October 26, 2012.

- Fields, Ronnie (May 18, 2011). "Previous underclass POYs". ESPN HS. Archived from the original on May 22, 2011. Retrieved September 5, 2013.

- Temkin, Barry (April 12, 2002). "An unknown legacy". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved October 26, 2012.

- Fuchs, Cynthia (October 24, 2012). "'Benji' Revisits the Story of Chicago Basketball Star Ben Wilson". PopMatters. Retrieved December 26, 2012.

- Schmitz, Brian (December 21, 2012). "Anderson still mourns late teammate". Orlando Sentinel.

- Wischnowsky, Dave (October 25, 2012). "What if Ben Wilson had Lived – And Become a Flyin' Illini?". Chicago Local. CBS. Retrieved October 28, 2012.

- "Ben Wilson's killer: 'I don't consider myself a criminal' ", CSN Chicago, 21 Nov 2012.

- Myers, Linnet (October 9, 1985). "Basketball Star's Slaying Described By Girlfriend". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved October 25, 2012.

- Berkow, Ira (February 14, 1993). "PRO BASKETBALL; A Dead Friend, a Living Memory". The New York Times. Retrieved October 25, 2012.

- Linnet, Myers (November 23, 1985). "Teen who killed Ben Wilson gets 40 years in prison". Chicago Tribune.

- Mount, Charles (May 8, 1985). "Ben Wilson's Family Sues Hospital, Medics". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved October 26, 2012.

- "Suit Settled In Death Of Basketball Star". Chicago Tribune. March 26, 1992.

- Chicago Tribune - An Unknown Legacy - April 12, 2002

- Bleacher Report - 8 Things To Know Before You Watch ESPN'S Documentary "Benji"

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on April 5, 2004. Retrieved April 5, 2004.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Benji, dir. Coodie and Chike, 2012.

- O'Neill, Lucas (April 25, 2012). "With an assist from Parker, 'Benji' debuts". ESPN HS. Retrieved October 26, 2012.

- Schurilla, Lexi (March 12, 2014). "Nunn Carries On 'Benji' Legacy". Illinois Athletics. Archived from the original on March 14, 2014. Retrieved March 14, 2014.

External links

- 20 Year Tragedy (Chicago Sports Review, December 2004)

- The Well-Guarded Guard (Sports Illustrated, November 20. 2006)

- Ben Wilson's death resonates 25 years later (Chicago Tribune, November 2009)

- Court opinion in People v. Moore (at Legal.com, May 1, 1992)

- 1997 Benji Wilson Nike Ad (Nike, 1997)