Benzoyl peroxide

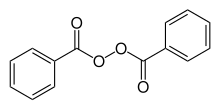

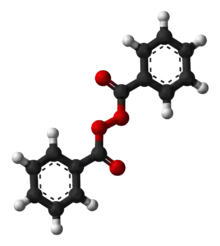

Benzoyl peroxide is a chemical compound (specifically, an organic peroxide) with structural formula (C

6H

5−C(=O)O−)

2, often abbreviated as (BzO)2. In terms of its structure, the molecule can be described as two benzoyl (C

6H

5−C(=O)−, Bz) groups connected by a peroxide (−O−O−). It is a white granular solid with a faint odour of benzaldehyde, poorly soluble in water but soluble in acetone, ethanol, and many other organic solvents. Benzoyl peroxide is an oxidizer, which is principally used as in the production of polymers.[2]

| |

Skeletal formula (top) Ball-and-stick model (bottom) | |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Benzac, Clearasil, PanOxyl, others |

| Other names | benzoperoxide, dibenzoyl peroxide (DBPO) |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Professional Drug Facts |

| MedlinePlus | a601026 |

| License data | |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| E number | E928 (glazing agents, ...) |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.002.116 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C14H10O4 |

| Molar mass | 242.230 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Density | 1.334 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 103 to 105 °C (217 to 221 °F) decomposes |

| Solubility in water | poor mg/mL (20 °C) |

| |

| |

| Data page | |

| Benzoyl peroxide (data page) | |

As a bleach, it has been used as a medication and a water disinfectant.[3][4] In specialized contexts, the name may be abbreviated as BPO.

As a medication, benzoyl peroxide is mostly used to treat acne, either alone or in combination with other treatments.[5] Some versions are sold mixed with antibiotics such as clindamycin.[6][7] It is on the WHO List of Essential Medicines,[8] and, in the US, it is available as an over-the-counter and generic medication.[9][6] It is also used in dentistry for teeth whitening.

Benzoyl peroxide is also used for bleaching flour, hair, and textiles[10][4] It is also used in the plastics industry.[3]

History

Benzoyl peroxide was first prepared and described by Liebig in 1858.[11] It was the first organic peroxide prepared intentionally.

In 1901, J. H. Kastle and his graduate student A. S. Loevenhart observed that the compound made the tincture of guaiacum tincture turn blue, a sign of oxygen being released.[12] Around 1905, Loevenhart reported on the successful use of BPO to treat various skin conditions, including burns, chronic varicose leg tumors, and tinea sycosis. He also reported animal experiments that showed the relatively low toxicity of the compound.[13][10][14]

Treatment with benzoyl peroxide was proposed for wounds by Lyon and Reynolds in 1929, and for sycosis vulgaris and acne varioliformis by Peck and Chagrin in 1934.[14] However, preparations were often of questionable quality.[10] It was officially approved for the treatment of acne in the US in 1960.[10]

Medical uses

Acne treatment

Benzoyl peroxide is effective for treating acne lesions. It does not induce antibiotic resistance.[15][16] It may be combined with salicylic acid, sulfur, erythromycin or clindamycin (antibiotics), or adapalene (a synthetic retinoid). Two common combination drugs include benzoyl peroxide/clindamycin and adapalene/benzoyl peroxide, an unusual formulation considering most retinoids are deactivated by peroxides. Combination products such as benzoyl peroxide/clindamycin and benzoyl peroxide/salicylic acid appear to be slightly more effective than benzoyl peroxide alone for the treatment of acne lesions.[16]

Benzoyl peroxide for acne treatment is typically applied to the affected areas in gel, cream, or liquid, in concentrations of 2.5% increasing through 5.0%, and up to 10%.[15] No strong evidence supports the idea that higher concentrations of benzoyl peroxide are more effective than lower concentrations.[15]

Mechanism of action

Classically, benzoyl peroxide is thought to have a three-fold activity in treating acne. It is sebostatic, comedolytic, and inhibits growth of Cutibacterium acnes, the main bacterium associated with acne.[15][17] In general, acne vulgaris is a hormone-mediated inflammation of sebaceous glands and hair follicles. Hormone changes cause an increase in keratin and sebum production, leading to blocked drainage. C. acnes has many lytic enzymes that break down the proteins and lipids in the sebum, leading to an inflammatory response. The free-radical reaction of benzoyl peroxide can break down the keratin, therefore unblocking the drainage of sebum (comedolytic). It can cause nonspecific peroxidation of C. acnes, making it bactericidal,[10] and it was thought to decrease sebum production, but disagreement exists within the literature on this.[17][18]

Some evidence suggests that benzoyl peroxide has an anti-inflammatory effect as well. In micromolar concentrations it prevents neutrophils from releasing reactive oxygen species, part of the inflammatory response in acne.[18]

Side effects

Application of benzoyl peroxide to the skin may result in redness, burning, and irritation. This side effect is dose-dependent.[5][9]

Because of these possible side effects, it is recommended to start with a low concentration and build up as appropriate, as the skin gradually develops tolerance to the medication. Skin sensitivity typically resolves after a few weeks of continuous use.[18][19] Irritation can also be reduced by avoiding harsh facial cleansers and wearing sunscreen prior to sun exposure.[19]

One in 500 people experience hypersensitivity to BPO and are liable to suffer burning, itching, crusting, and possibly swelling.[20][21] About one-third of people experience phototoxicity under exposure to ultraviolet (UVB) light.[22]

Dosage

In the U.S., the typical concentration for benzoyl peroxide is 2.5% to 10% for both prescription and over-the-counter drug preparations that are used in treatment for acne.

Other medical uses

Benzoyl peroxide is used in dentistry as a tooth whitening product.

Non-medical uses

Benzoyl peroxide is one of the most important organic peroxides in terms of applications and the scale of its production. It is often used as a convenient oxidant in organic chemistry.

Bleaching

Like most peroxides, it is a powerful bleaching agent. It has been used for the bleaching of flour, fats, oils, waxes, and cheeses, as well as a stain remover.[23]

Polymerization

Benzoyl peroxide is also used as a radical initiator to induce chain-growth polymerization reactions,[2] such as for polyester and poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) resins and dental cements and restoratives.[24] It is the most important among the various organic peroxides used for this purpose, a relatively safe alternative to the much more hazardous methyl ethyl ketone peroxide.[25][26] It is also used in rubber curing and as a finishing agent for some acetate yarns.[24]

Safety

Explosion hazard

Concentrated benzoyl peroxide is potentially explosive[27] like other organic peroxides, and can cause fires without external ignition. The hazard is acute for the pure material, so the compound is generally used as a solution or a paste. For example, cosmetics contain only a small percentage of benzoyl peroxide and pose no explosion risk.

Toxicity

Benzoyl peroxide breaks down in contact with skin, producing benzoic acid and oxygen, neither of which is very toxic.[28]

The carcinogenic potential of benzoyl peroxide has been investigated. A 1981 study published in the journal Science found that although benzoyl peroxide is not a carcinogen, it does promote cell growth when applied to an initiated tumor. The study concluded, "caution should be recommended in the use of this and other free radical-generating compounds".[29]

A 1999 IARC review of carcinogenicity studies found no convincing evidence linking BPO acne medication to skin cancers in humans. However, some animal studied found that the compound could act as a carcinogen and enhance the effect of known carcinogens.[24]

Skin irritation

In a 1977 study using a human maximization test, 76% of subjects acquired a contact sensitization to benzoyl peroxide. Formulations of 5% and 10% were used.[30]

The U.S. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health has developed criteria for a recommended standard for occupational exposure to benzoyl peroxide.[31]

Cloth staining

Contact with fabrics or hair, such as from still-moist acne medication, can cause permanent color dampening almost immediately. Even secondary contact can cause bleaching; for example, contact with a towel that has been used to wash off benzoyl peroxide-containing hygiene products.[32]

Reactivity

The original 1858 synthesis by Liebig reacted benzoyl chloride with barium peroxide,[11] a reaction that probably follows this equation:

- 2 C6H5C(O)Cl + BaO2 → (C6H5CO)2O2 + BaCl2

Benzoyl peroxide is usually prepared by treating hydrogen peroxide with benzoyl chloride under alkaline conditions.

- 2 C6H5COCl + H2O2 + 2 NaOH → (C6H5CO)2O2 + 2 NaCl + 2 H2O

The oxygen–oxygen bond in peroxides is weak. Thus, benzoyl peroxide readily undergoes homolysis (symmetrical fission), forming free radicals:

- (C6H5CO)2O2 → 2 C

6H

5CO•

2

The symbol • indicates that the products are radicals; i.e., they contain at least one unpaired electron. Such species are highly reactive. The homolysis is usually induced by heating. The half-life of benzoyl peroxide is one hour at 92 °C. At 131 °C, the half-life is one minute.[33]

References

- IUPAC Chemical Nomenclature and Structure Representation Division (2013). "P-65.7.5". In Favre HA, Powell WH (eds.). Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry: IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013. IUPAC–RSC. ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4.

- Klenk H, Götz PH, Siegmeier R, Mayr W. "Peroxy Compounds, Organic". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a19_199.

- Stellman JM (1998). Encyclopaedia of Occupational Health and Safety: Guides, indexes, directory. International Labour Organization. p. 104. ISBN 9789221098171. Archived from the original on 2017-09-18.

- Pommerville JC (2012). Alcamo's Fundamentals of Microbiology: Body Systems. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 214. ISBN 9781449605957. Archived from the original on 2017-09-18.

- World Health Organization (2009). Stuart MC, Kouimtzi M, Hill SR (eds.). WHO Model Formulary 2008. World Health Organization. pp. 307–308. hdl:10665/44053. ISBN 9789241547659.

- British national formulary : BNF 69 (69 ed.). British Medical Association. 2015. p. 820. ISBN 9780857111562.

- Braun-Falco O, Plewig G, Wolff HH, Burgdorf W (2012). Dermatology (2 ed.). Springer Science & Business Media. p. 1039. ISBN 9783642979316. Archived from the original on 2017-09-18.

- World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Hamilton R (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 173. ISBN 9781284057560.

- Plewig G, Kligman AM (2012). ACNE and ROSACEA (3 ed.). Springer Science & Business Media. p. 613. ISBN 9783642597152. Archived from the original on 2017-09-18.

- Brodie BC (1858). "Ueber die Bildung der Hyperoxyde organischer Säureradicale" [On the Formation of the Peroxides of Organic Acid Radicals]. Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 108: 79–83. doi:10.1002/jlac.18581080117.

- Kastle JH, Loevenhart AS (1901). "On the Nature of Certain Oxidizing Ferments". American Chemical Journal. 2: 539–566.

- Loevenhart AS (1905). "Benzoylsuperoxyds, ein neues therapeutisches Agens". Therap Monatscheftel (in German). 12: 426–428.

- Merker PC (March 2002). "Benzoyl peroxide: a history of early research and researchers". International Journal of Dermatology. 41 (3): 185–8. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.2002.01371.x. PMID 12010349. S2CID 24091844.

- Simonart T (December 2012). "Newer approaches to the treatment of acne vulgaris". American Journal of Clinical Dermatology. 13 (6): 357–64. doi:10.2165/11632500-000000000-00000. PMID 22920095. S2CID 12200694.

- Seidler EM, Kimball AB (July 2010). "Meta-analysis comparing efficacy of benzoyl peroxide, clindamycin, benzoyl peroxide with salicylic acid, and combination benzoyl peroxide/clindamycin in acne". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 63 (1): 52–62. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.07.052. PMID 20488582.

- Cotterill JA (1980-01-01). "Benzoyl peroxide". Acta Dermato-Venereologica. Supplementum. Suppl 89: 57–63. PMID 6162349.

- Worret, W.-I.; Fluhr, J. W. (April 2006). "Topische therapie mit benzoylperoxid, antibiotika und azelainsäure" [Acne therapy with topical benzoyl peroxide, antibiotics and azelaic acid]. Journal der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft (in German). 4 (4): 293–300. doi:10.1111/j.1610-0387.2006.05931.x. PMID 16638058. S2CID 6924764.

- Alldredge BK, ed. (2013). Applied Therapeutics: The Clinical Use of Drugs (10th ed.). Baltimore: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 949. ISBN 978-1609137137.

- Cunliffe WJ, Burke B (1982-01-01). "Benzoyl peroxide: lack of sensitization". Acta Dermato-Venereologica. 62 (5): 458–9. doi:10.2340/00015555462458459 (inactive 2021-01-14). PMID 6183909.CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2021 (link)

- "Benzoyl peroxide". Mayo Clinic. January 1, 2016. Archived from the original on July 18, 2016.

- Jeanmougin M, Pedreiro J, Bouchet J, Civatte J (1983-01-01). "[Phototoxic activity of 5% benzoyl peroxide in man. Use of a new methodology]". Dermatologica. 167 (1): 19–23. doi:10.1159/000249739. PMID 6628794.

- Stevens C. "Oxy10 for vinyl stains. Benzoyl peroxide removes stain from vinyl. Restore Dolls". Prilly Charmin Dolls. Archived from the original on 31 August 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- International Agency for Research on Cancer (1999): "Benzoyl peroxide". in Re-evaluation of Some Organic Chemicals, Hydrazine and Hydrogen Peroxide. Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, number 71, pages 345–358. ISBN 92-832-1271-1

- "Initiation By Diacyl Peroxides". Polymer Properties Database. Retrieved October 19, 2018.

- "Error - Evonik Industries AG" (PDF).

- Cartwright H (17 March 2005). "Chemical Safety Data: Benzoyl peroxide". Oxford University. Archived from the original on 12 October 2010. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- Benzoyl peroxide (PDF), SIDS Initial Assessment Report, Geneva: United Nations Environment Programme, April 2004

- Slaga TJ, Klein-Szanto AJ, Triplett LL, Yotti LP, Trosko KE (August 1981). "Skin tumor-promoting activity of benzoyl peroxide, a widely used free radical-generating compound". Science. 213 (4511): 1023–5. Bibcode:1981Sci...213.1023S. doi:10.1126/science.6791284. PMID 6791284.

- Leyden JJ, Kligman AM (October 1977). "Contact sensitization to benzoyl peroxide". Contact Dermatitis. 3 (5): 273–5. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1977.tb03674.x. PMID 145346. S2CID 33553359.

- "Criteria for a Recommended Standard: Occupational Exposure to Benzoyl Peroxide (77-166)". CDC - NIOSH Publications and Products. June 6, 2014. doi:10.26616/NIOSHPUB76128. Archived from the original on August 9, 2016. Retrieved 2016-07-15.

- Bojar RA, Cunliffe WJ, Holland KT (February 1995). "The short-term treatment of acne vulgaris with benzoyl peroxide: effects on the surface and follicular cutaneous microflora". The British Journal of Dermatology. 132 (2): 204–8. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1995.tb05014.x. PMID 7888356. S2CID 22468429.

- Li III H (1998). "Chapter 2" (PDF). Synthesis, Characterization and Properties of Vinyl Ester Matrix Resins (Ph.D.). University of Vermont. hdl:10919/30521. Archived from the original on 2006-09-20. Retrieved 2007-02-17.

External links

- "Benzoyl Peroxide". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- International Chemical Safety Card 0225

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0052". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- SIDS Initial Assessment Report from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)