Bessie Potter Vonnoh

Bessie Potter Vonnoh (August 17, 1872 – March 8, 1955) was an American sculptor best known for her small bronzes, mostly of domestic scenes, and for her garden fountains. Her stated artistic objective, as she told an interviewer in 1925, was to “look for beauty in the every-day world, to catch the joy and swing of modern American life.”[1]

Bessie Potter Vonnoh | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Robert Vonnoh, 1907 | |

| Born | Bessie Onahotema Potter August 17, 1872 |

| Died | March 8, 1955 (aged 82) |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Sculpture |

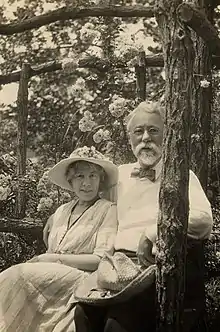

| Spouse(s) | Robert Vonnoh (1899–1933, until his death) Edward L. Keyes (1948–1949, until his death) |

| Elected | National Academy of Design (1921) American Academy of Arts and Letters (1931) |

Early years

Bessie Onahotema Potter was born in St Louis, Missouri,[2] the only child of Ohio natives Alexander and Mary McKenney Potter. Her father died in 1874, in an accident, at age 38.[3]:p. 7 By 1877, she and her mother had joined members of her mother's family in Chicago.[3]:p. 9

In school she enjoyed clay-modeling class and decided at an early age that she wanted to be a sculptor.[4] In 1886, at age 14, she enrolled in classes at the Art Institute of Chicago.[5] She was able to afford the tuition only because a local sculptor, Lorado Taft, hired her to work as a studio assistant, on Saturdays. From 1890 to 1891 she studied with Taft at the Art Institute, as she completed its sculptor courses.[3]:p. 11, 15

Early works

Vonnoh became one of the so-called "White Rabbits", women artists including Helen Farnsworth Mears and Janet Scudder who assisted Taft on the sculpture program for the Horticultural Building at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago.[6] She also produced an independent commission, the Personification of Art, for the Illinois State Building of the exposition.[2]

In 1895, she traveled to Europe, and met Auguste Rodin. Her best-known statuette, Young Mother (1896), used fellow "White Rabbit" Margaret Daisy Gerow (Mody) Proctor, wife of sculptor Alexander Phimister Proctor, and their infant son as models. In 1898, she received the commission for a bust of General Samuel W. Crawford for the Smith Memorial Arch in Philadelphia.[7][8]

In 1899 she married impressionist painter Robert Vonnoh, at his home in Rockland Lake, New York,[9] and honeymooned in Paris. At the 1900 Exposition Universelle, she was awarded a Bronze Medal for A Young Mother and exhibited another statuette, Girl Dancing.[10]

She exhibited at both the 1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York, receiving an honorable mention for A Young Mother,[10] and at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St Louis, Missouri, where she was awarded a Gold Medal for a group of ten works.[11]

Middle years

In March 1903, the New York Times noted that the Vonnohs were two of a dozen painters and sculptors who got together to create a building specifically for their studios, at 27 West Sixty-Seventh Street in Manhattan.[12] In mid-1903, the Vonnohs began summering in Old Lyme, Connecticut, and became long-time members of its Old Lyme Art Colony.[13]

Vonnoh's small-scale works were suited to the size and style of the average American home, and had broad appeal. Many of her works, such as Water lilies, were portraits. Vonnoh's statue Water lilies (1913) was based on the daughter of fellow artists Helen Savier and Frank DuMond at Lyme.[13] Vonnoh stated that she was "determined to prove that as perfect a likeness and as much beauty could be produced in statuettes twelve inches in height, and in busts of six inches, as could be had in the life-size and colossal productions suitable for so few houses."[3][14]

In December 1912, the New York Times, writing about her works at the New York Academy of Art, called her figurines "lovely", of a "charming style", and said "we must applaud once more her skillful harmonizing of detail in the contemporary costume, her selection of the most distinguished line for emphasis."[15] In 1915, Vonnoh exhibited in the Armory Show. In 1921, she was elected an academician of the National Academy of Design. She was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1931.[16]

In 1933, her husband died at age 75.[17] In 1937, Vonnoh completed her best-known large-scale work, the Burnett Memorial Fountain in Central Park.[18]

Later years

After her first husband's death, Vonnoh produced relatively little. She married again in 1948, to Dr. Edward L. Keyes, Jr., a widower, who died only nine months later.[19][20] Vonnoh herself died in New York City in 1955, at age 82.[21] She is buried alongside her first husband, Robert Vonnoh (1858 – 1933), in the Duck River Cemetery in Old Lyme, Connecticut.

Gallery

Enthroned, c. 1897

Enthroned, c. 1897 Girl Dancing, 1897

Girl Dancing, 1897 In Grecian Draperies, 1913

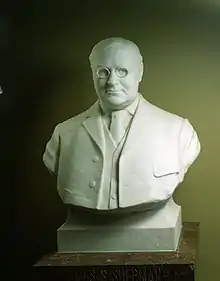

In Grecian Draperies, 1913 Bust of U.S. Vice President James S. Sherman, 1911

Bust of U.S. Vice President James S. Sherman, 1911 Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Bird Fountain, Oyster Bay, New York, 1927[22]

Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Bird Fountain, Oyster Bay, New York, 1927[22]

Exhibition History

References

- Thayer Tolles (April 2012). "Bessie Potter Vonnoh (1872-1955)". The Met. Retrieved 2019-03-02.

- Blumberg, Naomi. "Bessie Potter Vonnoh American sculptor". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Aronson, Julie (2008). Bessie Potter Vonnoh: Sculptor of Women. Ohio University Press. ISBN 978-0-8214-1800-0.

- "Bessie Potter Vonnoh papers, circa 1860-1991, bulk 1890-1955". Archives of American Art. Retrieved July 29, 2011.

- Benjamin Genocchio (November 21, 2008). "In Her Hands, Naturalism Won Out". New York Times.

- "Bessie Potter Vonnoh | National Museum of Women in the Arts". nmwa.org. Retrieved 2019-03-02.

- Tolles, Thayer (April 2012). "Bessie Potter Vonnoh (1872–1955)". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- Crawford bust

- "A Marriage of Artists; Miss Bessie Potter Quietly Wedded to R.W. Vonnoh". New York Times. September 21, 1899.

- Tolles, Thayer, ed. (1999). American sculpture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 559–561. ISBN 9780870999147. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- Ellis, Delancey M. (1907). NEW YORK AT THE LOUISIANA PURCHASE EXPOSITION ST. LOUIS, 1904 REPORT OF THE NEW YORK STATE COMMISSION. Albany: J. B. Lyon. p. 281. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- "A New Hive of Artists; Studios Built by a Dozen Painters to Suit Themselves -- Practical Side of the Sixty-seventh St. Building". New York Times. March 27, 1903.

- Cooley, Jeffrey W. (1993). Fine American Paintings. Old Lyme, CT: The Cooley Gallery. pp. 58–59.

- Kim, Linda (June 2014). "Separate Spheres: Potterines, Gender, and Domestic Sculpture in Turn-of-the-Century America". American Art. 28 (2): 2–25. doi:10.1086/677963. S2CID 192987832.

- "Art at Home and Abroad; From the Academic to the Modern Is the Range Shown in Exhibition of Sculpture at the Academy". New York Times. December 22, 1912.

- "Deceased Members". American Academy of Arts and Letters. Archived from the original on July 26, 2011. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- "Robert Vonnoh, Noted Hartford Artist, Dies". The Hartford Courant. December 29, 1933.

- Burnett Memorial

- "Mrs. Bessie P. Vonnoh a Bride". New York Times. June 27, 1948.

- "Edward Loughborough Keyes, Jr., Papers: Part 2 (special collections)". Georgetown University. Archived from the original on 2012-03-22. Retrieved 2011-07-30.

- "Bessie P. Yonnoh, Sculptor, was 82; Widow of Dr. Edward Keyes Is Dead--Her Works Won Many Medals in Shows". New York Times. March 9, 1955.

- Lane, Laura. "Major renovations of TR Sanctuary to begin soon". LI Herald Oyster Bay. Long Island Herald. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- "Bessie Potter Vonnoh | National Museum of Women in the Arts". nmwa.org. Retrieved 2019-03-02.

Further reading

- Aronson, Julie. Bessie Potter Vonnoh: Sculptor of Women. Athens: Ohio University Press, 2008;

- Baigell, Matthew (1979) "Vonnoh, Bessie Potter" Dictionary of American Art Harper & Row, Publishers, New York;

- Bowman, John S. (ed.) (1995) "Vonnoh, Bessie (Onahotema) Potter" The Cambridge Dictionary of American Biography Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England;

- Falk, Peter Hastings (1985) "Vonnoh, Bessie Potter" Who Was Who in American Art: 1898-1947 Sound View Press, Madison, CT;

- Garraty, John A. and Carnes, Mark C. (eds.) (1999) "Vonnoh, Bessie Onahotema Potter" American National Biography Oxford University Press, New York;

- Heller, Jules and Heller, Nancy G. (1995) "Vonnoh, Bessie Potter" North American Women Artists of the Twentieth Century: A biographical dictionary Garland Publishing, New York

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bessie Potter Vonnoh. |