Bible translations into Japanese

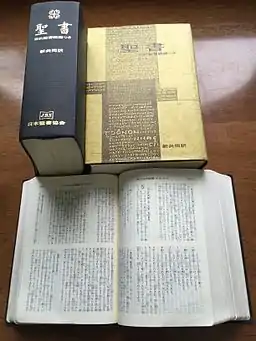

There are two main translations of the Bible into Japanese widely in use today—the New Interconfessional Version (新共同訳聖書) and the New Japanese Bible (新改訳聖書). New Interconfessional Translation Version is published by the Japan Bible Society and the New Japanese Bible is published by Inochinokotoba-sha(いのちのことば社). There are with different translation goals. The New Japanese Version aims to be used as a literal translation using modern Japanese while the New Interconfessional Version aims to be ecumenically used by all Christian denominations and must therefore conform to various theologies. Protestant Evangelicals most often use the New Japanese Version, but the New Interconfessional Version is the most widely distributed and the one used by the Catholic Church, the United Church of Christ, Lutheran Church factions and many Anglicans in Japan.[1][2][3][4][5]

Jesuit missions

Japanese Bible translation began when Catholic missionaries (Kirishitan) entered Japan in 1549, and Jesuits published portions of the New Testament in Kyoto, in 1613, though no copy survives. Exactly how much was translated by the Jesuit Mission is not confirmed. It would seem that at least Gospels for the Sundays of the year and other Bible pericopes were translated.[6][7] Shortly afterwards, however, Christianity was banned and all the missionaries were exiled. That translation of the Bible is now lost.[8][9]

Protestant missionaries

Work on translation started outside Japan in the 19th century by Protestant missionaries interested in Japan. Karl Gutzlaff of the London Missionary Society translated the Gospel of John in Macau in 1837, referring to the Chinese version of Robert Morrison (Chinese Shentian Shengshu 神天聖書). Bernard Jean Bettelheim, who had been a missionary in the Ryūkyū Kingdom (Okinawa) and who had been exiled, translated the Bible to Ryūkyūan and published the Gospel of Luke and John, Acts of the Apostles and the Epistle to the Romans in Hong Kong in 1855.[10] Japan re-opened in 1858, and many missionaries came into the country. They found that intellectuals could read Chinese texts easily, so they used Chinese Bibles at first. However, the proportion of intellectuals was only in the region of 2% and in order to spread their religion across the country more effectively, a Japanese Bible became necessary. Incidentally, a second reversion of Bettelheim's Luke was published in 1858, intercolumnated with the Chinese Delegates' version, and designed for missionary use in Japan. This version, with its heavy Ryūkyūan flavor, proved just as unsuitable as Chinese-only Bibles. After leaving Asia and immigrating to the United States, Bettelheim continued work on his translations, and newly revised editions of Luke, John, and the Acts, now closer to Japanese than Ryūkyūan, were published posthumously in Vienna in 1873-1874 with the assistance of August Pfizmaier.

Meiji Version, 1887

A translation was done by James Curtis Hepburn, of the Presbyterian Mission, and Samuel Robbins Brown, of the Reformed Church of America. It is presumed that Japanese intellectual assistants helped translate Bridgman and Culbertson's Chinese Bible (1861) into Japanese, and Hepburn and Brown adjusted the phrases. The Gospels of Mark, Matthew and John were published in 1872.[11] Hepburn's project was taken over by a Missionary Committee, sponsored by the American Bible Society, British and Foreign Bible Society and the Scottish Bible Society in Tokyo. Their New Testament and Old Testament, called the Meiji Version (明治元訳 meiji genyaku, "Meiji era Original Translation"), was published in 1880 and 1887 respectively. They translated from a Greek text as well as the King James version.[12][13][14]

Taisho Revised Version, 1917

A revision of the New Testament, the Taisho Revised Version (大正改訳聖書 taisho kaiyaku seisho, "Taisho era Revised Translation of Scripture") appeared in 1917 during the Taishō period. This version was widely read even outside of Christian society. Its phrases are pre-modern style, but became popular in Japan. This was based on the Nestle-Aland Greek Text and the English Revised Version (RV).[15][16][17]

Bible, Japanese Colloquial, 1954, 1955, 1975, 1984, 2002

After World War II, the Japan Bible Society (日本聖書協会, nihon seisho kyōkai) translated the "Bible, Japanese Colloquial (口語訳聖書, kōgoyaku seisho)". The New Testament being ready in 1954 and the Old Testament in 1955.[18] It was adopted by certain Protestant churches but never became really popular, perhaps because of its poor literary style. This translation was based on the Revised Standard Version (RSV).[19][20]

Japanese Living Bible, 1977, 1993, 2016

Based on the New Living Translation this translation has an informal literary style which attempts to capture the meaning of the original texts in modern Japanese. Revised version released in 2016 by Word of Life press.

1977 version available online in PDF form from Biblica and at bible.com

New Japanese Bible, 1965, 1970, 1978, 2003, 2017

In 1970 the NSK (日本聖書刊行会, nihon seisho kankōkai) - different from the Japan Bible Society (日本聖書協会, nihon seisho kyōkai) - released the first edition of the New Japanese Bible (新改訳聖書, shin kaiyaku seisho, "New Revised Version of the Bible") which was translated from Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek (Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia and Nestle-Aland Novum Testamentum Graece).[21] The Shin Kaiyaku endeavors to translate theologically difficult passages in a way that is linguistically accurate to the source texts, to strike a balance between word-for-word and thought-for-thought but erring toward a literal translation.

The latest edition was released in 2017.

New Interconfessional Translation, 1987, 1988, 2018

The Second Vatican Council decided to promote ecumenism and emphasized respect for the Bible. Consortia between the Catholic and the Protestant churches were organized and translation projects started in many countries, including Japan. The collaboration committee published the Interconfessional Translation Bible (共同訳聖書, kyōdō yaku seisho) of the New Testament in 1978, but it was not widely supported by both congregations, Catholic and Protestant.[22][23] The committee then published a revised version in 1987, the New Interconfessional Translation Bible (新共同訳聖書, shin kyōdō yaku seisho), which included the Old Testament.[24][25] It has been distributed well by various organisations such as Gideons International, the next edition was planned to be released in 2016.

Translation spent eight years from 2010 to 2017. In terms of translation theory, while the Joint Bible followed Eugene Naida's theory of dynamic correspondence (with formal and dynamic view thorough within bible), and criticism of it, the New Joint Bible changed its direction to formal correspondence , The Bible Society's Joint Translation Bible, referring to the Scopos theory proposed by Lawrence de Vries in the Netherlands, adopted the scopos "to aim for a dignified Japanese suitable for reading in worship."[26]

The Bible Society Joint Translation Bible is a Japanese translation of the Bible. This is the Japanese translation of the Bible by the Bible Society of Japan, and has been published as a new translation for the first time in 31 years since the New Joint Translation Bible. The first edition was published on December 3, 2018.[27] The official English name is Japan Bible Society Interconfessional Version.[28]

Other translators

There are many other Japanese translations of the Bible by various organizations and individuals.

Catholic versions

In the Catholic Church, Emile Raguet of the MEP translated the New Testament from the Vulgate Latin version and published it in 1910. It was treated as the standard text by Japanese Catholics.[29] Federico Barbaro colloquialized it (published in 1957). He went on to translate the Old Testament in 1964.[30]

The Franciscans completed a translation of the whole Bible, based on the Greek and Hebrew text, in 1978. This project was inspired by the Jerusalem Bible.[31]

Orthodox versions

In the Orthodox Church, Nicholas and Tsugumaro Nakai translated the New Testament as an official text in 1901,[32] but the 1954 Colloquial Translation is often used.

The Japanese Orthodox Bible, of course, describes the Orthodox Yasuyuki Takahashi as "the most credible Bible that can be used regardless of the religion", but even Protestant missionaries in the Meiji era have apostles. Some have described the Gospels of the Book and John as "much better than any translation currently in existence".

Some people don't appreciate the style very much like the Protestant Fujihara Fujio, but in the modern Bible, etc., it is described as an accurate translation. On the other hand, it is true that this translation is difficult, and in the 1930s, orthodox people called for revision. However, Nikolai himself should raise the understanding of the believers toward the translation by having the Orthodox teachings understood correctly, and on the contrary, he was opposed to damaging the accuracy of the translation by asking the public.

There were Even in the 1930s debate, Nakai Kuma Maro was not only able to break down some of Nikolai's elaborate translations, but also had to maintain its magnificent style, so he understood the need for translation. However, expressed opposition to easy translation. As a result, some observers have said that the Japanese Orthodox Church translation has been preserved to date, and that the long-standing inheritance itself can be appreciated.[33]

Jehovah's Witnesses, 1973, 1985, 2019

Japanese was among the first 8 languages into which the New World Translation was translated.[34] Jehovah's Witnesses first released the Japanese New World Translation as 「クリスチャン・ギリシャ語聖書 新世界訳」 (New World Translation of the Christian Greek Scriptures) in 1973.[35] This Bible, however, contains Christian Greek Scriptures only. By 1982, the first complete Bible was finally released in Japanese and it is called as 新世界訳聖書 (New World Translation of the Holy Scriptures).[36][37] By the same year, tens of thousands of copies had been printed in Japan printery.[38] Not long after, in 1985, another edition of the Japanese New World translation was released, this release also includes the new Reference Bible.[39] Both the Standard and Reference edition of this Bible is based from the English 1984 edition of the New World Translation of the Holy Scriptures which was released on 1984 in United States.[40]

After several years since the released in 1985, on April 13, 2019, a member of the Governing Body of Jehovah's Witnesses, Stephen Lett, released the revised edition of the New World Translation of the Holy Scriptures with a same name—新世界訳聖書 in Japanese.[41] This new Bible is based from the English 2013 revision of the New World Translation of the Holy Scriptures which was released at the 129th annual meeting of the Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society of Pennsylvania.[42][43] This revised edition in Japanese includes the use of more modern and understandable language (look at the chart below), clarified Biblical expression, appendixes, and many more.[44][37]

Comparison

| Translation | John 3:16 |

|---|---|

| Japanese Interconfessional Translation (1987)(ja:新共同訳聖書) | 神は、その独り子をお与えになったほどに、世を愛された。独り子を信じる者が一人も滅びないで、永遠の命を得るためである。 |

| New Japanese Bible (1965)(ja:新改訳聖書) | 神は、実に、そのひとり子をお与えになったほどに、世を愛された。それは御子を信じる者が、ひとりとして滅びることなく、永遠のいのちを持つためである。 |

| Japanese Colloquial Bible (1954)(ja:口語訳聖書) | 神はそのひとり子を賜わったほどに、この世を愛して下さった。それは御子を信じる者がひとりも滅びないで、永遠の命を得るためである。 |

| Translation | John 1 (verses vary) |

|---|---|

| Gutzlaff (1837) | John 1:1-2 ハジマリニ カシコイモノゴザル、コノカシコイモノ ゴクラクトトモニゴザル、コノカシコイモノワゴクラク。ハジマリニ コノカシコイモノ ゴクラクトトモニゴザル。 |

| Bettelheim "Loochooan" version (Hong Kong, 1855) | John 1:1-2 ハジマリニ カシコイモノ ヲテ, コノカシコイモノヤ シヤウテイトトモニヲタン。 コノ カシコイモノ ハジマリニ シヤウテイト トモニ ヲタン。[45] |

| Hepburn (1872) | John 1:1-4 元始(はじめ)に言霊(ことだま)あり 言霊は神とともにあり 言霊ハ神なり。この言霊ハはじめに神とともにあり。よろづのものこれにてなれり なりしものハこれにあらでひとつとしてなりしものハなし。これに生(いのち)ありし いのちは人のひかりなりし。 |

| Bettelheim revised (hiragana) version (Vienna, 1873) | John 1:1-2 はじめに かしこいものあり かしこいものハ 神と ともにいます かしこいものハすなわち神 |

| Meiji version (1880) | John 1:3 万物(よろづのもの)これに由(より)て造(つく)らる造(つくら)れたる者に一つとして之に由(よ)らで造られしは無(なし) |

| Orthodox church Translation(1902) | John 1:1-3

太初(はじめ)に言(ことば)有り、言は神(かみ)と共に在り、言は即(すなはち)神なり。 是(こ)の言は太初に神と共に在り。万物(ばんぶつ)は彼に由(より)て造(つく)られたり、凡(およそ)造(つく)られたる者には、一(いつ)も彼に由(よ)らずして造られしは無し。 |

| Taisho Revised Version (1917) | John 1:1-3 太初(はじめ)に言(ことば)あり、言(ことば)は神と偕(とも)にあり、言(ことば)は神なりき。この言(ことば)は太初(はじめ)に神とともに在(あ)り、萬(よろづ)の物これに由(よ)りて成り、成りたる物に一つとして之によらで成りたるはなし。 |

| Shinkeiyaku(Nagai)version (1928) | John 1:1-4 初に言(ことば)ありき、また言は神と偕(とも)にありき、また言は神なりき。 此の者は初に神と偕にありき。 すべての物、彼によりて刱(はじ)まれり、また刱まりたる物に、一つとして彼を離れて刱まりしはなし。 彼に生(いのち)ありき、また此の生は人の光なりき。 |

| Colloquial version (1954) | John 1:1-3 初めに言(ことば)があった。言(ことば)は神と共にあった。言(ことば)は神であった。この言(ことば)は初めに神と共にあった。すべてのものは、これによってできた。できたもののうち、一つとしてこれによらないものはなかった。 |

| Barbaro (1957) | John 1:1-3 はじめにみことばがあった。みことばは神とともにあった。みことばは神であった。かれは、はじめに神とともにあり、万物はかれによってつくられた。つくられた物のうち、一つとしてかれによらずつくられたものはない。 |

| Shinkaiyaku Seisho (1973) | John 1:1-3 初めに、ことばがあった。ことばは神とともにあった。ことばは神であった。この方は、初めに神とともにおられた。すべてのものは、この方によって造られた。造られたもので、この方によらずにできたものは一つもない。 |

| Franciscan (1978) | John 1:1-3 初めにみ言葉があった。/み言葉は神と共にあった。/み言葉は神であった。/み言葉は初めに神と共にあった。/すべてのものは、み言葉によってできた。/できたもので、み言葉によらずに/できたものは、何一つなかった。 |

| The New Interconfessional Translation (1987) | John 1:1-3 初めに言(ことば)があった。言(ことば)は神と共にあった。言(ことば)は神であった。この言(ことば)は、初めに神と共にあった。万物は言(ことば)によって成った、成ったもので、言(ことば)によらず成ったものは何一つなかった。 |

| Japanese Living Bible (2016) | John 1:1-4 まだこの世界に何もない時から、キリストは神と共におられました。キリストは、いつの時代にも生きておられます。キリストは神だからです。 このキリストが、すべてのものをお造りになりました。そうでないものは一つもありません。 キリストには永遠のいのちがあります。全人類に光を与えるいのちです。 |

| New World Translation (2019) | John 1:1-4 初めに,言葉と呼ばれる方がいた。言葉は神と共にいて,言葉は神のようだった。 この方は初めに神と共にいた。 全てのものはこの方を通して存在するようになり,彼を通さずに存在するようになったものは一つもない。 |

References

- 日本福音同盟 - Japan Evangelical Association

- 日本福音同盟『日本の福音派』Japan Evangelical Association

- 新改訳聖書刊行会『聖書翻訳を考える』

- 中村敏『日本における福音派の歴史』ISBN 4264018269

- 尾山令仁『聖書翻訳の歴史と現代訳』

- Handbook of Christianity in Japan: Mark Mullins - 2003 Among these writings were the Gospels for the Sundays of the year and other Bible pericopes, such as Passion ... Captain John Saris, an English adventurer who spent about two years in Japan, made the following entry in his diary while in Kyoto on 9 October 1613: In this cittie of Meaco, the Portingall Jesuitts haue a verie statelie Colledge

- The Bible translator 18 United Bible Societies - 1967 "In his diary for October 9th, when he visited Miako (Kyoto), we find the entry : In this cittie of Meaco, the Portingall Iesuitts ... which identifies one volume as 'A Japanese New Testament printed in Miako by the Jesuits in 1613'."

- Arimichi Ebizawa, "Bible in Japan --A History of Japanese Bible Translation,"(In Japanese) Kodansha, 1989, ISBN 4-06-158906-7, Section 1

- Norihisa Suzuki, Japanese in the Bible: A History of Translation (In Japanese). Iwanamishoten, 2006, ISBN 4-00-023664-4, Section 1

- Arimichi Ebizawa, "Bible in Japan --A History of Japanese Bible Translation,"(In Japanese) Kodansha, 1989, ISBN 4-06-158906-7, Section 3

- Arimichi Ebizawa, "Bible in Japan --A History of Japanese Bible Translation,"(In Japanese) Kodansha, 1989, ISBN 4-06-158906-7, Section 4

- Arimichi Ebizawa, "Bible in Japan --A History of Japanese Bible Translation,"(In Japanese) Kodansha, 1989, ISBN 4-06-158906-7, Section 6,7

- Norihisa Suzuki, Japanese in the Bible: A History of Translation, (In Japanese) Iwanamishoten, 2006, ISBN 4-00-023664-4, Section 4

- Kenzo Tagawa, "New Tastement as a Text," (In Japanese) Keisoshobou, 1997, ISBN 4-326-10113-X,pp.620-621

- Arimichi Ebizawa, "Bible in Japan --A History of Japanese Bible Translation,"(In Japanese) Kodansha, 1989, ISBN 4-06-158906-7, Section 12

- Norihisa Suzuki, Japanese in the Bible: A History of Translation, (In Japanese) Iwanamishoten, 2006, ISBN 4-00-023664-4, Section 5

- Kenzo Tagawa, "New Tastement as a Text," (In Japanese) Keisoshobou, 1997, ISBN 4-326-10113-X,p.622

- http://www.bible.or.jp/e/history.html

- Norihisa Suzuki, Japanese in the Bible: A History of Translation, (In Japanese) Iwanamishoten, 2006, ISBN 4-00-023664-4, Section 6

- Kenzo Tagawa, "New Testament as a Text," (In Japanese) Keisoshobou, 1997, ISBN 4-326-10113-X,p.623-633

-

新約はネストレの校訂本二四版、旧約はキッテルの三版以後のものに基づき、訳業を進めたが、

— The New Japanese Bible Postscript - Norihisa Suzuki, Japanese in the Bible: A History of Translation, (In Japanese) Iwanamishoten, 2006, ISBN 4-00-023664-4, pp.148-168

- Kenzo Tagawa, "New Tastement as a Text," (In Japanese) Keisoshobou, 1997, ISBN 4-326-10113-X,pp.651-661

- Norihisa Suzuki, Japanese in the Bible: A History of Translation, (In Japanese) Iwanamishoten, 2006, ISBN 4-00-023664-4, pp.168-177

- Kenzo Tagawa, "New Testament as a Text," (In Japanese) Keisoshobou, 1997, ISBN 4-326-10113-X,pp.661-692

- 聖書 聖書協会共同訳について (PDF), 日本聖書協会, 2018

- "『聖書 聖書協会共同訳』が銀座・教文館などで発売開始". クリスチャンプレス (in Japanese). 3 December 2018. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- "プレスリリース 新翻訳聖書の書名が決定―『聖書聖書協会共同訳』" (PDF). 日本聖書協会. 1 October 2017. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- Arimichi Ebizawa, "Bible in Japan --A History of Japanese Bible Translation,"(In Japanese) Kodansha, 1989, ISBN 4-06-158906-7, Section 10

- Kenzo Tagawa, "New Testament as a Text," (In Japanese) Keisoshobou, 1997, ISBN 4-326-10113-X,pp.648-649

- Kenzo Tagawa, "New Tastement as a Text," (In Japanese) Keisoshobou, 1997, ISBN 4-326-10113-X,pp.649-650

- Arimichi Ebizawa, "Bible in Japan --A History of Japanese Bible Translation,"(In Japanese) Kodansha, 1989, ISBN 4-06-158906-7, Section 11

- アレクセイ・ポタポフ 2011, p. 116

- "Do You Seek Hidden Treasures?", The Watchtower, 1 December 1989, page 17

- "日本語の「新世界訳聖書」改訂版が発表される". JW.ORG (FOOTNOTE 1 | 脚注 1) (in Japanese). 15 April 2019.

- Handbook of Christianity in Japan, Part 5 by Mark Mullins, Brill, 2003, page 216

- "「あらゆる良い活動を行う用意が完全に整い」ました!". JW.ORG (in Japanese). 15 April 2019.

- "‘Lengthening the Tent Cords’ in Japan", The Watchtower, 15 June 1985, page 25

- "A Happy Day for Japan’s Missionaries", The Watchtower, 1 November 1985, page 15

- "Part 1—Modern Stewardship of God's Sacred Word". wol.jw.org. 1 November 1985. p. 28.

- "New World Translation Released in Japanese". JW.ORG. 15 April 2019.

- "Annual Meeting Report 2013 | Jehovah's Witnesses". JW.ORG. 11 November 2013.

- "前書き — ものみの塔 オンライン・ライブラリー". wol.jw.org (in Japanese). 15 April 2019.

- "A2 この改訂版の特色 — ものみの塔 オンライン・ライブラリー". wol.jw.org (in Japanese). 15 April 2019. pp. 2042–2045.

- Quoted in Kazamasa Iha's "Gutslaff and Bettelheim : A Contrastive Study of Translations of St. John : Material I (Chapters I-V)"

External links

Downloadable

- Japanese Bible Download 日本のバイブル, at Downloadbibles/Japanese

Online

- Classical 文語訳, at ibibles.net

- Colloquial 口語訳, at ibibles.net

- Colloquial, 1955 edition, at Bible.is

- New Interconfessional Version, at Bible.is

- New World Translation, at JW.ORG

- Orthodox church Translation