Bilinski dodecahedron

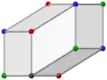

In geometry, the Bilinski dodecahedron is a 12-sided convex polyhedron with congruent rhombic faces. It has the same topology but different geometry from the face-transitive rhombic dodecahedron. It is a zonohedron.

.png.webp) (Animation) | |||

(Dimensioning) | |||

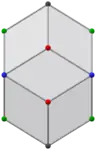

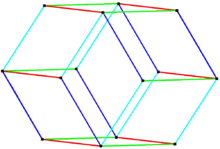

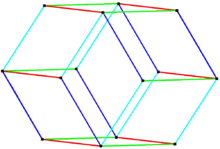

Orthogonal projections that look like golden rhombohedra | |||

Other orthogonal projections | |||

.png.webp) .png.webp) Pairs of golden rhombohedra (Animations) |

History

This shape appears in a 1752 book by John Lodge Cowley, labeled as the dodecarhombus.[1][2] It is named after Stanko Bilinski, who rediscovered it in 1960.[3] Bilinski himself called it the rhombic dodecahedron of the second kind.[4] Bilinski's discovery corrected a 75-year-old omission in Evgraf Fedorov's classification of convex polyhedra with congruent rhombic faces.[5]

Properties

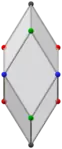

| degree | color | coordinates | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | red | (0, ±1, ±1) | .png.webp) |

| green | (±φ, 0, ±φ) | ||

| 4 | blue | (±φ, ±1, 0) | |

| black | (0, 0, ±φ2) | ||

Like its Catalan twin, the Bilinski dodecahedron has eight vertices of degree 3 and six of degree 4. But due to its different symmetry, it has four different kinds of vertices: the two on the vertical axis, and four in each axial plane.

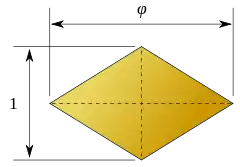

Its faces are 12 golden rhombi of three different kinds: 2 with alternating blue and red vertices (front and back), 2 with alternating blue and green vertices (left and right), and 8 with all four kinds of vertices.

The symmetry group of this solid is the same as that of a rectangular cuboid: D2h. It has eight elements, and is a subgroup of octahedral symmetry. The three axial planes are also the symmetry planes of this solid.

Relation to rhombic dodecahedron

In a 1962 paper,[6] H. S. M. Coxeter claimed that the Bilinski dodecahedron could be obtained by an affine transformation from the rhombic dodecahedron, but this is false. For, in the Bilinski dodecahedron, the long body diagonal is parallel to the short diagonals of two faces, and to the long diagonals of two other faces. In the rhombic dodecahedron, the corresponding body diagonal is parallel to four short face diagonals, and in any affine transformation of the rhombic dodecahedron this body diagonal would remain parallel to four equal-length face diagonals. Another difference between the two dodecahedra is that, in the rhombic dodecahedron, all the body diagonals connecting opposite degree-4 vertices are parallel to face diagonals, while in the Bilinski dodecahedron the shorter body diagonals of this type have no parallel face diagonals.[5]

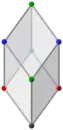

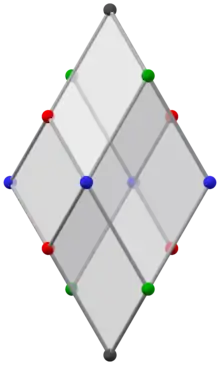

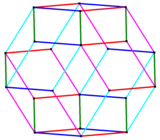

Related zonohedra

The Bilinski dodecahedron can be formed from the rhombic triacontahedron (another zonohedron with thirty golden rhombic faces) by removing or collapsing two zones or belts of ten and eight golden rhombic faces with parallel edges. Removing only one zone of ten faces produces the rhombic icosahedron. Removing three zones of ten, eight, and six faces produces the golden rhombohedra.[4][5] The Bilinski dodecahedron can be dissected into four golden rhombohedra, two of each type.[7]

The vertices of these zonohedra can be computed by linear combinations of 3 to 6 vectors. A belt mn means a belt representing n directional vectors, and containing (at most) m coparallel congruent edges. The Bilinski dodecahedron has 4 belts of 6 coparallel edges.

These zonohedra are projection envelopes of the hypercubes, with n-dimensional projection basis, with golden ratio, φ. The specific basis for n=6 is:

- x = (1, φ, 0, -1, φ, 0)

- y = (φ, 0, 1, φ, 0, -1)

- z = (0, 1, φ, 0, -1, φ)

For n=5 the basis is the same with the 6th column removed. For n=4 the 5th and 6th columns are removed.

| Solid name | Triacontahedron | Icosahedron | Dodecahedron | Hexahedron | Rhombus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full symmetry |

Ih Order 120 |

D5d Order 20 |

D2h Order 8 |

D3d Order 12 |

Dih2 Order 4 |

| (2(n-1))n Belts | 106 | 85 | 64 | 43 | 22 |

| n(n-1) Faces | 30 | 20 (−10) |

12 (−8) |

6 (−6) |

2 (−4) |

| 2n(n-1) Edges | 60 | 40 (−20) |

24 (−16) |

12 (−12) |

4 (−8) |

| n(n-1)+2 Vertices | 32 | 22 (−10) |

14 (−8) |

8 (−6) |

4 (−4) |

| Solid image |  |

|

|

| |

| Parallel edges image |  |

|

|||

| Dissection | 10 |

5 |

2 |

||

| Projective polytope | 6-cube | 5-cube | 4-cube | 3-cube | 2-cube |

| Projective n-cube image |

|

|

|

References

- Hart, George W. (2000), "A color-matching dissection of the rhombic enneacontahedron", Symmetry: Culture and Science, 11 (1–4): 183–199, MR 2001417.

- Cowley, John Lodge (1752), Geometry Made Easy; Or, a New and Methodical Explanation of the Elements of Geometry, London, Plate 5, Fig. 16. As cited by Hart (2000).

- Bilinski, S. (1960), "Über die Rhombenisoeder", Glasnik Mat. Fiz. Astr., 15: 251–263, Zbl 0099.15506.

- Cromwell, Peter R. (1997), Polyhedra: One of the most charming chapters of geometry, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 156, ISBN 0-521-55432-2, MR 1458063.

- Grünbaum, Branko (2010), "The Bilinski dodecahedron and assorted parallelohedra, zonohedra, monohedra, isozonohedra, and otherhedra", The Mathematical Intelligencer, 32 (4): 5–15, doi:10.1007/s00283-010-9138-7, hdl:1773/15593, MR 2747698.

- Coxeter, H. S. M. (1962), "The classification of zonohedra by means of projective diagrams", Journal de Mathématiques Pures et Appliquées, 41: 137–156, MR 0141004. Reprinted in Coxeter, H. S. M. (1968), Twelve geometric essays, Carbondale, Ill.: Southern Illinois University Press, MR 0310745 (The Beauty of Geometry. Twelve Essays, Dover, 1999, MR1717154).

- "Golden Rhombohedra", CutOutFoldUp, retrieved 2016-05-26

External links

- VRML model, George W. Hart: www

.georgehart .com /virtual-polyhedra /vrml /rhombic _dodecahedron _of _second _kind .wrl - animation and coordinates, David I. McCooey: dmccooey

.com /polyhedra /BilinskiDodecahedron .html - A new Rhombic Dodecahedron from Croatia!, YouTube video by Matt Parker