Biological Weapons Convention

The Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production and Stockpiling of Bacteriological (Biological) and Toxin Weapons and on their Destruction (usually referred to as the Biological Weapons Convention, abbreviation: BWC, or Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention, abbreviation: BTWC) was the first multilateral disarmament treaty banning the production of an entire category of weapons.[3]

Long name:

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

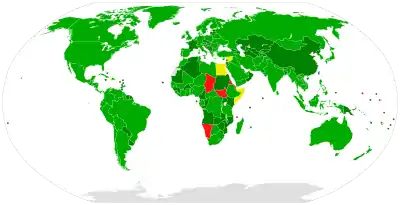

Participation in the Biological Weapons Convention

| |||

| Signed | 10 April 1972 | ||

| Location | London, Moscow, and Washington, D.C. | ||

| Effective | 26 March 1975 | ||

| Condition | Ratification by 22 states | ||

| Signatories | 109 | ||

| Parties | 183 as of December 2020 [1] (complete list) | ||

| Depositary | United States, United Kingdom, Russian Federation | ||

| Languages | Chinese, English, French, Russian and Spanish [2] | ||

The Convention was the result of prolonged efforts by the international community to establish a new instrument that would supplement the 1925 Geneva Protocol. The Geneva Protocol prohibits use but not possession or development of chemical and biological weapons.

A draft of the BWC, submitted by the British[4] was opened for signature on 10 April 1972 and entered into force 26 March 1975 when twenty-two governments had deposited their instruments of ratification.[5] It commits the 183 states which are party to it as of August 2019 to prohibit the development, production, and stockpiling of biological and toxin weapons. However, the absence of any formal verification regime to monitor compliance has limited the effectiveness of the Convention. An additional five states have signed the BWC but have yet to ratify the treaty.

The scope of the BWC's prohibition is defined in Article 1 (the so-called general purpose criterion). This includes all microbial and other biological agents or toxins and their means of delivery (with exceptions for medical and defensive purposes in small quantities). Subsequent Review Conferences have reaffirmed that the general purpose criterion encompasses all future scientific and technological developments relevant to the Convention. It is not the objects themselves (biological agents or toxins), but rather certain purposes for which they may be employed which are prohibited; similar to Art.II, 1 in the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC). Permitted purposes under the BWC are defined as prophylactic, protective and other peaceful purposes. The objects may not be retained in quantities that have no justification or which are inconsistent with the permitted purposes.

As stated in Article 1 of the BWC:

"Each State Party to this Convention undertakes never in any circumstances to develop, produce, stockpile or otherwise acquire or retain:

- (1) Microbial or other biological agents, or toxins whatever their origin or method of production, of types and in quantities that have no justification for prophylactic, protective or other peaceful purposes;

- (2) Weapons, equipment or means of delivery designed to use such agents or toxins for hostile purposes or in armed conflict."

The United States Congress passed the Bioweapons Anti-Terrorism Act in 1989 to implement the Convention. The law applies the Convention's convent to countries and private citizens, and criminalizes violations of the Convention.[6]

Summary

- Article I: Never under any circumstances to acquire or retain biological weapons.

- Article II: To destroy or divert to peaceful purposes biological weapons and associated resources prior to joining.

- Article III: Not to transfer, or in any way assist, encourage or induce anyone else to acquire or retain biological weapons.

- Article IV: To take any national measures necessary to implement the provisions of the BWC domestically.

- Article V: To consult bilaterally and multilaterally to solve any problems with the implementation of the BWC.

- Article VI: To request the UN Security Council to investigate alleged breaches of the BWC and to comply with its subsequent decisions.

- Article VII: To assist States which have been exposed to a danger as a result of a violation of the BWC.

- Article VIII: To do all of the above in a way that encourages the peaceful uses of biological science and technology.

Membership

The BWC has 183 States Parties as of August 2019, with Tanzania the most recent to become a party. The Republic of China (Taiwan) had deposited an instrument of ratification before the changeover of the United Nations seat to the People's Republic of China.

Several countries made reservations when ratifying the agreement declaring that it did not imply their complete satisfaction that the Treaty allows the stockpiling of biological agents and toxins for "prophylactic, protective or other peaceful purposes", nor should it imply recognition of other countries they do not recognise.

Of the UN member states and UN observer which are not a party to the treaty, five have signed but not ratified the BWC while a further 10 have neither signed nor ratified the agreement.

Implementation Support Unit

In 2006, the Sixth Review Conference to the BWC created an Implementation Support Unit (ISU) within the Geneva Branch of the United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs.[7]

The ISU’s mandate was renewed at the Seventh and Eighth Review Conferences.[7] The ISU is funded by the States Parties to the BWC.[8]

Verification and compliance issues

A long process of negotiation to add a verification mechanism began in the 1990s. Previously, at the second Review Conference of State Parties in 1986, member states agreed to strengthen the treaty by reporting annually on Confidence Building Measures (CBMs) to the United Nations. Currently, less than half of the treaty signatories actually submit these voluntary annual reports.[9] The following Review Conference in 1991 established a group of government experts (known as VEREX). Negotiations towards an internationally binding verification protocol to the BWC took place between 1995 and 2001 in a forum known as the Ad Hoc Group. On 25 July 2001, the Bush administration, after conducting a review of policy on biological weapons, decided that the proposed protocol did not suit the national interests of the United States.

Payment issues

Implementation of the BWC, and the review conferences to support further progress, have recently been hobbled by financial considerations. In 2018, the Meeting of States Parties was cut short due to a funding shortfall,[10] and the continued nonpayment or underpayment by states is a continuing issue and topic of conversation in 2019.[11] As of July 31, 2019, the total outstanding debt is $251,382.46, spread among 95 countries with outstanding debts. Some of these debts are minimal, in part due to the sliding scale of dues, with 34 countries' outstanding debts under $100, and a further 43 under $1,000. Brazil had the highest outstanding debt, owing $110,948.23, while Venezuela had the second highest debt, $51,272.91.[12]

Financial shortfalls almost caused a cancellation of state-party meetings in December 2019. However, BWC members agreed at this conference, held in Geneva December 4–7, 2018, to establish a working capital fund, financed by voluntary contributions, to provide short-term financing – including paying the convention's small secretariat—pending receipt of contributions from member countries.[13]

Review conferences

States Parties have formally reviewed the operation of the BWC at quinquennial review conferences held in 1980, 1986, 1991, 1996, 2001/02, 2006, 2011, and 2016. During these review conferences, States Parties have reaffirmed that the scope of the Convention extends to new scientific and technological developments, and have also instituted confidence-building data-exchanges in order to enhance transparency and strengthen the BWC. Review conferences, other than the Fifth, adopted additional understandings or agreements that have interpreted, defined or elaborated the meaning or scope of a BWC provision, or that have provided instructions, guidelines or recommendations on how a provision should be implemented. These additional understandings are contained in the Final Declarations of the Review Conferences. There has been an increase in the percentage of delegates from States Parties who have been women since the first review conference, with just 7 percent in 1980 to 26 percent in 2011.[14]

Fifth Review Conference

The BWC lacks an enforcement mechanism against parties who might seek to develop, produce or stockpile agents of germ warfare. For many years, diplomats negotiated in Geneva to arrive at legally binding mechanisms to enforce compliance. The Fifth Review Conference took place in November/December 2001, at a time of heightened concern about international terrorism in the wake of the September 11 attacks and the 2001 anthrax attacks. However, the United States government decided to pull out of discussions on strengthening the convention by adding an effective legally binding enforcement mechanism. This in effect scuttled talks on the issue, stunning negotiators from other countries. Many analysts, including Matthew Meselson, a biologist at Harvard University who helped draft a treaty banning biological weapons, and biological and chemical weapons specialist Amy Smithson of the Washington-based Stimson Center, criticized the U.S. decision as undermining international efforts against non-proliferation and as contradicting U.S. government rhetoric regarding the alleged biological weapons threat posed by Iraq and other U.S. foes.[15] The Conference was suspended for one year. When it was reconvened in November 2002, the Fifth Review Conference decided to hold annual meetings of States Parties over the inter-sessional period leading up to the Review Conference in 2006 to discuss and promote common understanding and effective action on a range of other topics.[16]

Agreement was reached on convening an intersessional programme, including annual Meetings of States Parties and Meetings of Experts (see section below for details).[17]

Sixth Review Conference

In the final document of the Sixth Review Conference, held in 2006, it simply "notes" that the meetings "functioned as an important forum for exchange of national experiences and in depth deliberations among States Parties" and that they "engendered greater common understanding on steps to be taken to further strengthen the implementation of the Convention". The Conference "endorses the consensus outcome documents" from the Meeting of States Parties.

The Sixth Review Conference agreed to establish a second Inter-Sessional Process. The topics agreed upon were:

i. Ways and means to enhance national implementation, including enforcement of national legislation, strengthening of national institutions and coordination among national law enforcement institutions.

ii. Regional and sub regional cooperation on BWC implementation.

iii. National, regional and international measures to improve biosafety and biosecurity, including laboratory safety and security of pathogens and toxins.

iv. Oversight, education, awareness raising, and adoption and/or development of codes of conduct with the aim to prevent misuse in the context of advances in bio science and bio technology research with the potential of use for purposes prohibited by the Convention.

v. With a view to enhancing international cooperation, assistance and exchange in biological sciences and technology for peaceful purposes, promoting capacity building in the fields of disease surveillance, detection, diagnosis, and containment of infectious diseases: (1) for States Parties in need of assistance, identifying requirements and requests for capacity enhancement, and (2) from States Parties in a position to do so, and international organizations, opportunities for providing assistance related to these fields.

vi. Provision of assistance and coordination with relevant organizations upon request by any State Party in the case of alleged use of biological or toxin weapons, including improving national capabilities for disease surveillance, detection and diagnosis and public health systems.

Topics i and ii were dealt with in 2007, iii and iv in 2008, v in 2009, and vi in 2010. For the second Inter-Sessional Process, the Meetings of Experts for each year was reduced to one week.

Seventh Review Conference

The Seventh Review Conference was held in Geneva from 5 to 22 December 2011. The Final Declaration document affirmed that "under all circumstances the use of bacteriological (biological) and toxin weapons is effectively prohibited by the Convention" and "the determination of States parties to condemn any use of biological agents or toxins other than for peaceful purposes, by anyone at any time."[18]

Eighth Review Conference

The Eighth BWC Review Conference, held in Geneva in November 2016, had minimal achievements, according to Arms Control Today, and passed a final document that echoed the final document of the Seventh Review Conference. While Western countries wanted to pursue ways to address rapidly advancing changes in technology, most of the participating countries, including Iran and some states of the Non-Aligned Movement, viewed the results as a missed opportunity to advance measures to strengthen the legally binding accord that bans development of biological agents, and wanted negotiations to restart effort to pass the BWC Protocol.[19]

Ninth Review Conference

The Ninth BWC Review Conference will be held in Geneva in late 2021. On December 9, 2019, Sri Lanka was elected chairman of the 2020 Meeting of State Parties, an intersessional which has been postponed to April 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic[20] and will discuss the agenda for the Ninth Review Conference.[21]

Intersessional programme

Ever since the Fifth Review Conference in 2001, annual BWC meetings were held between Review Conferences, referred to as the intersessional programme. The intersessional programme includes both week-long annual Meetings of States Parties—aiming to discuss, and promote a common understanding and effective action on the topics identified by the Review Conference—as well as two-week-long annual Meetings of Experts, which serve as preparation for the Meeting of States Parties.[17][22] As agreed during the 2017 Meeting of States Parties, the Meetings of Experts (MXs) of the current intersessional programme will consider the following topics:[23]

- MX1 on Cooperation and Assistance, with a Particular Focus on Strengthening Cooperation and Assistance under Article X

- MX2 on Review of Developments in the Field of Science and Technology Related to the Convention

- MX3 on Strengthening National Implementation

- MX4 on Assistance, Response and Preparedness

- MX5 on Institutional Strengthening of the Convention

See also

References

- "Status of the Biological Weapons Convention". United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- Biological Weapons Convention, Article 15.

- The text of the Convention, as well as the key documents from recent meetings can be found on the BWC Implementation Support Unit website.

- "History – World Wars: Silent Weapon: Smallpox and Biological Warfare". BBC. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- Trakimavicius, Lukas (24 May 2018). "Is Russia Violating the Biological Weapons Convention?". Atlantic Council. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- Coen, Bob (2009). Dead Silence: Fear and Terrorism on the Anthrax Trail. Berkeley, California: CounterPoint. pp. 205. ISBN 978-1-58243-509-1.

- "Biological Weapons Convention | Implementation Support Unit". United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- "Biological Weapons Convention | Role of the Implementation Support Unit". United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- "Electronic Confidence Building Measures Portal for the Biological Weapons Convention".

- https://www.unog.ch/80256EE600585943/(httpPages)/C550A7F7B6D5A9A0C125830E002B2728?OpenDocument

- https://www.unog.ch/80256EE600585943/(httpPages)/E8A05357EECA5490C12583BE00578053?OpenDocument

- https://www.onug.ch/80256EDD006B8954/(httpAssets)/92E86B141A6C795CC125844F00514234/$file/Disarmament+Receivables+For+Website+31+July+2019+Annexes.pdf

- Jenifer Mackby (2019). "BWC Meeting Stumbles Over Money, Politics". Arms Control Today. Retrieved 24 December 2019.

- Danskin, Kathleen (23 June 2014). "Women as Agents of Positive Change in Biosecurity". Science & Diplomacy. 3 (2).

- Washington Post, 19 September 2002, archived at: Peter Slevin, “U.S. Drops Bid to Strengthen Germ Warfare Accord,”

- BWC document BWC/CONF.V/17 (2001 and 2002), available via the BWC Implementation Support Unit website or the UN Official Documents System.

- "Final Document of the Fifth Review Conference to the BWC" (PDF). United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs. 22 February 2002. Article 18. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- "Final Document of the Seventh Review Conference" (PDF). BWC/CONF.VII/7. United Nations. 13 January 2012. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- Jenifer Mackby (2017). "Disputes Mire BWC Review Conference". Arms Control Today. Retrieved 24 December 2019.

- "Meetings under the Biological Weapons Convention – UNODA". Archived from the original on 20 December 2020. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- "Sri Lanka elected Chair of Biological Weapons Convention Meet". ColomboPage. 2019. Retrieved 24 December 2019.

- "Biological Weapons Convention | Meetings and Documents". United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- "2017 Report of the Meeting of States Parties". undocs.org. 19 December 2017. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

External links

- "Official website of the Biological Weapons Convention". United Nations.

- "Full text of the Biological Weapons Convention". United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs Treaty Database.

- Meetings Place of the United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs. A page with details on disarmament meetings, including documents and presentations.

- "Treaties and Regimes: The Biological Weapons Convention". Nuclear Threat Initiative. 27 April 2020.

- "The Biological Weapons Convention (BWC) At A Glance". Arms Control Association. March 2020.

- "The Historical Context of the Origins of the Biological Weapons Convention (BWC)". University College London.

- "Understanding Biological Disarmament: Final Report (.pdf)" (PDF). July 2017.

- Failed establishment of an international Organisation for the Prohibition of Biological Weapons (OPBW) , Boudewijn de Jonge, 2006

- Enforcing non-proliferation: The European Union and the 2006 BTWC Review Conference, Chaillot Paper No. 93, November 2006, European Union Institute for Security Studies