Bolivia

Bolivia[lower-alpha 1] /bəˈlɪviə/ (![]() listen), officially the Plurinational State of Bolivia,[lower-alpha 2][9][10] is a landlocked country located in western-central South America. The constitutional capital is Sucre, while the seat of government and executive capital is La Paz. The largest city and principal industrial center is Santa Cruz de la Sierra, located on the Llanos Orientales (tropical lowlands), a mostly flat region in the east of the country.

listen), officially the Plurinational State of Bolivia,[lower-alpha 2][9][10] is a landlocked country located in western-central South America. The constitutional capital is Sucre, while the seat of government and executive capital is La Paz. The largest city and principal industrial center is Santa Cruz de la Sierra, located on the Llanos Orientales (tropical lowlands), a mostly flat region in the east of the country.

Plurinational State of Bolivia | |

|---|---|

| |

_-_BOL_-_UNOCHA.svg.png.webp) | |

| Capital | Sucre (constitutional and judicial) La Paz (executive and legislative) |

| Largest city | Santa Cruz 17°48′S 63°10′W |

| Official languages[2] | |

| Ethnic groups (2009[3]) |

|

| Religion (2018)[4] | 88.9% Christianity —70.0% Roman Catholic —17.2% Protestant —1.7% Other Christian 9.3% No religion 1.2% Other religions 0.6% No answer |

| Demonym(s) | Bolivian |

| Government | Unitary presidential constitutional republic |

| Luis Arce | |

| David Choquehuanca | |

| Legislature | Plurinational Legislative Assembly |

| Chamber of Senators | |

| Chamber of Deputies | |

| Independence from Spain | |

• Declared | 6 August 1825 |

• Recognized | 21 July 1847 |

| 14 November 1945 | |

• Current constitution | 7 February 2009 |

| Area | |

• Total | 1,098,581 km2 (424,164 sq mi) (27th) |

• Water (%) | 1.29 |

| Population | |

• 2019[5] estimate | 11,428,245 (83rd) |

• Density | 10.4/km2 (26.9/sq mi) (224th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2019 estimate |

• Total | $89.018 billion[6] (88th) |

• Per capita | $7,790[6] (123rd) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2019 estimate |

• Total | $40.687 billion[6] (90th) |

• Per capita | $3,823[6] (117th) |

| Gini (2018) | medium |

| HDI (2019) | high · 107th |

| Currency | Boliviano (BOB) |

| Time zone | UTC−4 (BOT) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +591 |

| ISO 3166 code | BO |

| Internet TLD | .bo |

The sovereign state of Bolivia is a constitutionally unitary state, divided into nine departments. Its geography varies from the peaks of the Andes in the West, to the Eastern Lowlands, situated within the Amazon basin. It is bordered to the north and east by Brazil, to the southeast by Paraguay, to the south by Argentina, to the southwest by Chile, and to the northwest by Peru. One-third of the country is within the Andean mountain range. With 1,098,581 km2 (424,164 sq mi) of area, Bolivia is the fifth largest country in South America, after Brazil, Argentina, Peru, and Colombia (and alongside Paraguay, one of the only two landlocked countries in the Americas), the 27th largest in the world, the largest landlocked country in the Southern Hemisphere and the world's seventh largest landlocked country, after Kazakhstan, Mongolia, Chad, Niger, Mali and Ethiopia.

The country's population, estimated at 11 million,[11] is multiethnic, including Amerindians, Mestizos, Europeans, Asians and Africans. Spanish is the official and predominant language, although 36 indigenous languages also have official status, of which the most commonly spoken are Guarani, Aymara and Quechua languages.

Before Spanish colonization, the Andean region of Bolivia was part of the Inca Empire, while the northern and eastern lowlands were inhabited by independent tribes. Spanish conquistadors arriving from Cusco and Asunción took control of the region in the 16th century. During the Spanish colonial period Bolivia was administered by the Real Audiencia of Charcas. Spain built its empire in large part upon the silver that was extracted from Bolivia's mines. After the first call for independence in 1809, 16 years of war followed before the establishment of the Republic, named for Simón Bolívar.[12] Over the course of the 19th and early 20th century Bolivia lost control of several peripheral territories to neighboring countries including the seizure of its coastline by Chile in 1879. Bolivia remained relatively politically stable until 1971, when Hugo Banzer led a CIA-supported coup d'état which replaced the socialist government of Juan José Torres with a military dictatorship headed by Banzer; Torres was murdered in Buenos Aires, Argentina by a right-wing death squad in 1976. Banzer's regime cracked down on leftist and socialist opposition and other forms of dissent, resulting in the torture and deaths of a number of Bolivian citizens. Banzer was ousted in 1978 and later returned as the democratically elected president of Bolivia from 1997 to 2001.

Modern Bolivia is a charter member of the UN, IMF, NAM, OAS, ACTO, Bank of the South, ALBA, and USAN. Bolivia remains the second poorest country in South America, though they have slashed poverty rates and are the fastest growing economy in South America (GDP wise). It is a developing country, with a high ranking in the Human Development Index. Its main economic activities include agriculture, forestry, fishing, mining, and manufacturing goods such as textiles, clothing, refined metals, and refined petroleum. Bolivia is very rich in minerals, including tin, silver, lithium, and copper.

Etymology

Bolivia is named after Simón Bolívar, a Venezuelan leader in the Spanish American wars of independence.[13] The leader of Venezuela, Antonio José de Sucre, had been given the option by Bolívar to either unite Charcas (present-day Bolivia) with the newly formed Republic of Peru, to unite with the United Provinces of Rio de la Plata, or to formally declare its independence from Spain as a wholly independent state. Sucre opted to create a brand new state and on 6 August 1825, with local support, named it in honor of Simón Bolívar.[14]

The original name was Republic of Bolívar. Some days later, congressman Manuel Martín Cruz proposed: "If from Romulus, Rome, then from Bolívar, Bolivia" (Spanish: Si de Rómulo, Roma; de Bolívar, Bolivia). The name was approved by the Republic on 3 October 1825. In 2009, a new constitution changed the country's official name to "Plurinational State of Bolivia" in recognition of the multi-ethnic nature of the country and the enhanced position of Bolivia's indigenous peoples under the new constitution.

History

Pre-colonial

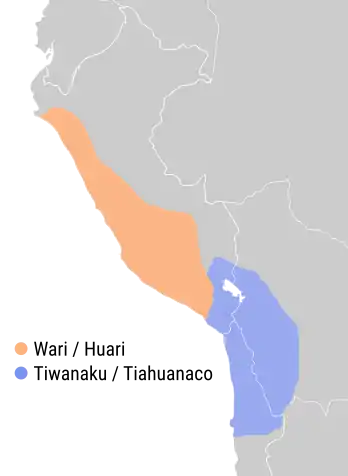

The region now known as Bolivia had been occupied for over 2,500 years when the Aymara arrived. However, present-day Aymara associate themselves with the ancient civilization of the Tiwanaku Empire which had its capital at Tiwanaku, in Western Bolivia. The capital city of Tiwanaku dates from as early as 1500 BC when it was a small, agriculturally based village.[15]

The community grew to urban proportions between AD 600 and AD 800, becoming an important regional power in the southern Andes. According to early estimates, the city covered approximately 6.5 square kilometers (2.5 square miles) at its maximum extent and had between 15,000 and 30,000 inhabitants.[16] In 1996 satellite imaging was used to map the extent of fossilized suka kollus (flooded raised fields) across the three primary valleys of Tiwanaku, arriving at population-carrying capacity estimates of anywhere between 285,000 and 1,482,000 people.[17]

Around AD 400, Tiwanaku went from being a locally dominant force to a predatory state. Tiwanaku expanded its reaches into the Yungas and brought its culture and way of life to many other cultures in Peru, Bolivia, and Chile. Tiwanaku was not a violent culture in many respects. In order to expand its reach, Tiwanaku exercised great political astuteness, creating colonies, fostering trade agreements (which made the other cultures rather dependent), and instituting state cults.[18]

The empire continued to grow with no end in sight. William H. Isbell states "Tiahuanaco underwent a dramatic transformation between AD 600 and 700 that established new monumental standards for civic architecture and greatly increased the resident population."[19] Tiwanaku continued to absorb cultures rather than eradicate them. Archaeologists note a dramatic adoption of Tiwanaku ceramics into the cultures which became part of the Tiwanaku empire. Tiwanaku's power was further solidified through the trade it implemented among the cities within its empire.[18]

Tiwanaku's elites gained their status through the surplus food they controlled, collected from outlying regions and then redistributed to the general populace. Further, this elite's control of llama herds became a powerful control mechanism as llamas were essential for carrying goods between the civic centre and the periphery. These herds also came to symbolize class distinctions between the commoners and the elites. Through this control and manipulation of surplus resources, the elite's power continued to grow until about AD 950. At this time a dramatic shift in climate occurred,[20] causing a significant drop in precipitation in the Titicaca Basin, believed by archaeologists to have been on the scale of a major drought.

As the rainfall decreased, many of the cities farther away from Lake Titicaca began to tender fewer foodstuffs to the elites. As the surplus of food decreased, and thus the amount available to underpin their power, the control of the elites began to falter. The capital city became the last place viable for food production due to the resiliency of the raised field method of agriculture. Tiwanaku disappeared around AD 1000 because food production, the main source of the elites' power, dried up. The area remained uninhabited for centuries thereafter.[20]

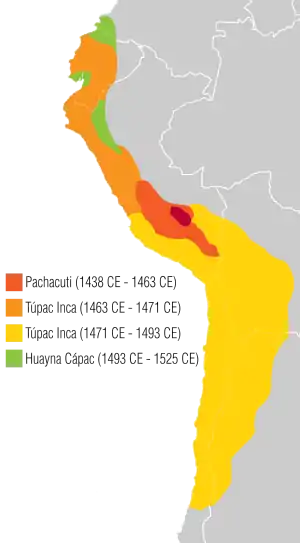

Between 1438 and 1527, the Inca empire expanded from its capital at Cusco, Peru. It gained control over much of what is now Andean Bolivia and extended its control into the fringes of the Amazon basin.

Colonial period

The Spanish conquest of the Inca empire began in 1524, and was mostly completed by 1533. The territory now called Bolivia was known as Charcas, and was under the authority of the Viceroy of Lima. Local government came from the Audiencia de Charcas located in Chuquisaca (La Plata—modern Sucre). Founded in 1545 as a mining town, Potosí soon produced fabulous wealth, becoming the largest city in the New World with a population exceeding 150,000 people.[21]

By the late 16th century, Bolivian silver was an important source of revenue for the Spanish Empire.[22] A steady stream of natives served as labor force under the brutal, slave conditions of the Spanish version of the pre-Columbian draft system called the mita.[23] Charcas was transferred to the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata in 1776 and the people from Buenos Aires, the capital of the Viceroyalty, coined the term "Upper Peru" (Spanish: Alto Perú) as a popular reference to the Royal Audiencia of Charcas. Túpac Katari led the indigenous rebellion that laid siege to La Paz in March 1781,[24] during which 20,000 people died.[25] As Spanish royal authority weakened during the Napoleonic wars, sentiment against colonial rule grew.

Independence and subsequent wars

The struggle for independence started in the city of Sucre on 25 May 1809 and the Chuquisaca Revolution (Chuquisaca was then the name of the city) is known as the first cry of Freedom in Latin America. That revolution was followed by the La Paz revolution on 16 July 1809. The La Paz revolution marked a complete split with the Spanish government, while the Chuquisaca Revolution established a local independent junta in the name of the Spanish King deposed by Napoleon Bonaparte. Both revolutions were short-lived and defeated by the Spanish authorities in the Viceroyalty of the Rio de La Plata, but the following year the Spanish American wars of independence raged across the continent.

Bolivia was captured and recaptured many times during the war by the royalists and patriots. Buenos Aires sent three military campaigns, all of which were defeated, and eventually limited itself to protecting the national borders at Salta. Bolivia was finally freed of Royalist dominion by Marshal Antonio José de Sucre, with a military campaign coming from the North in support of the campaign of Simón Bolívar. After 16 years of war the Republic was proclaimed on 6 August 1825.

.svg.png.webp)

In 1836, Bolivia, under the rule of Marshal Andrés de Santa Cruz, invaded Peru to reinstall the deposed president, General Luis José de Orbegoso. Peru and Bolivia formed the Peru-Bolivian Confederation, with de Santa Cruz as the Supreme Protector. Following tension between the Confederation and Chile, Chile declared war on 28 December 1836. Argentina separately declared war on the Confederation on 9 May 1837. The Peruvian-Bolivian forces achieved several major victories during the War of the Confederation: the defeat of the Argentine expedition and the defeat of the first Chilean expedition on the fields of Paucarpata near the city of Arequipa. The Chilean army and its Peruvian rebel allies surrendered unconditionally and signed the Paucarpata Treaty. The treaty stipulated that Chile would withdraw from Peru-Bolivia, Chile would return captured Confederate ships, economic relations would be normalized, and the Confederation would pay Peruvian debt to Chile. However, the Chilean government and public rejected the peace treaty. Chile organized a second attack on the Confederation and defeated it in the Battle of Yungay. After this defeat, Santa Cruz resigned and went to exile in Ecuador and then Paris, and the Peruvian-Bolivian Confederation was dissolved.

Following the renewed independence of Peru, Peruvian president General Agustín Gamarra invaded Bolivia. On 18 November 1841, the battle de Ingavi took place, in which the Bolivian Army defeated the Peruvian troops of Gamarra (killed in the battle). After the victory, Bolivia invaded Perú on several fronts. The eviction of the Bolivian troops from the south of Peru would be achieved by the greater availability of material and human resources of Peru; the Bolivian Army did not have enough troops to maintain an occupation. In the district of Locumba – Tacna, a column of Peruvian soldiers and peasants defeated a Bolivian regiment in the so-called Battle of Los Altos de Chipe (Locumba). In the district of Sama and in Arica, the Peruvian colonel José María Lavayén organized a troop that managed to defeat the Bolivian forces of Colonel Rodríguez Magariños and threaten the port of Arica. In the battle of Tarapacá on 7 January 1842, Peruvian militias formed by the commander Juan Buendía defeated a detachment led by Bolivian colonel José María García, who died in the confrontation. Bolivian troops left Tacna, Arica and Tarapacá in February 1842, retreating towards Moquegua and Puno.[26] The battles of Motoni and Orurillo forced the withdrawal of Bolivian forces occupying Peruvian territory and exposed Bolivia to the threat of counter-invasion. The Treaty of Puno was signed on 7 June 1842, ending the war. However, the climate of tension between Lima and La Paz would continue until 1847, when the signing of a Peace and Trade Treaty became effective.

The estimated population of the main three cities in 1843 was La Paz 300,000, Cochabamba 250,000 and Potosi 200,000.[27]

A period of political and economic instability in the early-to-mid-19th century weakened Bolivia. In addition, during the War of the Pacific (1879–83), Chile occupied vast territories rich in natural resources south west of Bolivia, including the Bolivian coast. Chile took control of today's Chuquicamata area, the adjoining rich salitre (saltpeter) fields, and the port of Antofagasta among other Bolivian territories.

Since independence, Bolivia has lost over half of its territory to neighboring countries.[28] Through diplomatic channels in 1909, it lost the basin of the Madre de Dios River and the territory of the Purus in the Amazon, yielding 250,000 km2 to Peru.[29] It also lost the state of Acre, in the Acre War, important because this region was known for its production of rubber. Peasants and the Bolivian army fought briefly but after a few victories, and facing the prospect of a total war against Brazil, it was forced to sign the Treaty of Petrópolis in 1903, in which Bolivia lost this rich territory. Popular myth has it that Bolivian president Mariano Melgarejo (1864–71) traded the land for what he called "a magnificent white horse" and Acre was subsequently flooded by Brazilians, which ultimately led to confrontation and fear of war with Brazil.

In the late 19th century, an increase in the world price of silver brought Bolivia relative prosperity and political stability.

Early 20th century

During the early 20th century, tin replaced silver as the country's most important source of wealth. A succession of governments controlled by the economic and social elite followed laissez-faire capitalist policies through the first 30 years of the 20th century.[30]

Living conditions of the native people, who constitute most of the population, remained deplorable. With work opportunities limited to primitive conditions in the mines and in large estates having nearly feudal status, they had no access to education, economic opportunity, and political participation. Bolivia's defeat by Paraguay in the Chaco War (1932–35), where Bolivia lost a great part of the Gran Chaco region in dispute, marked a turning-point.[31][32][33]

The Revolutionary Nationalist Movement (MNR), the most historic political party, emerged as a broad-based party. Denied its victory in the 1951 presidential elections, the MNR led a successful revolution in 1952. Under President Víctor Paz Estenssoro, the MNR, having strong popular pressure, introduced universal suffrage into his political platform and carried out a sweeping land-reform promoting rural education and nationalization of the country's largest tin mines.

Late 20th century

Twelve years of tumultuous rule left the MNR divided. In 1964, a military junta overthrew President Estenssoro at the outset of his third term. The 1969 death of President René Barrientos Ortuño, a former member of the junta who was elected president in 1966, led to a succession of weak governments. Alarmed by the rising Popular Assembly and the increase in the popularity of President Juan José Torres, the military, the MNR, and others installed Colonel (later General) Hugo Banzer Suárez as president in 1971. He returned to the presidency in 1997 through 2001. Juan José Torres, who had fled Bolivia, was kidnapped and assassinated in 1976 as part of Operation Condor, the U.S.-supported campaign of political repression by South American right-wing dictators.[34]

The United States' Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) financed and trained the Bolivian military dictatorship in the 1960s. The revolutionary leader Che Guevara was killed by a team of CIA officers and members of the Bolivian Army on 9 October 1967, in Bolivia. Félix Rodríguez was a CIA officer on the team with the Bolivian Army that captured and shot Guevara.[35] Rodriguez said that after he received a Bolivian presidential execution order, he told "the soldier who pulled the trigger to aim carefully, to remain consistent with the Bolivian government's story that Che had been killed in action during a clash with the Bolivian army." Rodriguez said the US government had wanted Che in Panama, and "I could have tried to falsify the command to the troops, and got Che to Panama as the US government said they had wanted", but that he had chosen to "let history run its course" as desired by Bolivia.[36]

Elections in 1979 and 1981 were inconclusive and marked by fraud. There were coups d'état, counter-coups, and caretaker governments. In 1980, General Luis García Meza Tejada carried out a ruthless and violent coup d'état that did not have popular support. He pacified the people by promising to remain in power only for one year. At the end of the year, he staged a televised rally to claim popular support and announced, "Bueno, me quedo", or, "All right; I'll stay [in office]."[37] After a military rebellion forced out Meza in 1981, three other military governments in 14 months struggled with Bolivia's growing problems. Unrest forced the military to convoke the Congress, elected in 1980, and allow it to choose a new chief executive. In October 1982, Hernán Siles Zuazo again became president, 22 years after the end of his first term of office (1956–60).

Democratic transition

In 1993, Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada was elected president in alliance with the Tupac Katari Revolutionary Liberation Movement, which inspired indigenous-sensitive and multicultural-aware policies.[38] Sánchez de Lozada pursued an aggressive economic and social reform agenda. The most dramatic reform was privatization under the "capitalization" program, under which investors, typically foreign, acquired 50% ownership and management control of public enterprises in return for agreed upon capital investments.[39][40] In 1993, Sanchez de Lozada introduced the Plan de Todos, which led to the decentralization of government, introduction of intercultural bilingual education, implementation of agrarian legislation, and privatization of state owned businesses. The plan explicitly stated that Bolivian citizens would own a minimum of 51% of enterprises; under the plan, most state-owned enterprises (SOEs), though not mines, were sold.[41] This privatization of SOEs led to a neoliberal structuring.[42]

The reforms and economic restructuring were strongly opposed by certain segments of society, which instigated frequent and sometimes violent protests, particularly in La Paz and the Chapare coca-growing region, from 1994 through 1996. The indigenous population of the Andean region was not able to benefit from government reforms.[43] During this time, the umbrella labor-organization of Bolivia, the Central Obrera Boliviana (COB), became increasingly unable to effectively challenge government policy. A teachers' strike in 1995 was defeated because the COB could not marshal the support of many of its members, including construction and factory workers.

1997–2002 General Banzer Presidency

In the 1997 elections, General Hugo Banzer, leader of the Nationalist Democratic Action party (ADN) and former dictator (1971–78), won 22% of the vote, while the MNR candidate won 18%. At the outset of his government, President Banzer launched a policy of using special police-units to eradicate physically the illegal coca of the Chapare region. The MIR of Jaime Paz Zamora remained a coalition-partner throughout the Banzer government, supporting this policy (called the Dignity Plan).[44] The Banzer government basically continued the free-market and privatization-policies of its predecessor. The relatively robust economic growth of the mid-1990s continued until about the third year of its term in office. After that, regional, global and domestic factors contributed to a decline in economic growth. Financial crises in Argentina and Brazil, lower world prices for export commodities, and reduced employment in the coca sector depressed the Bolivian economy. The public also perceived a significant amount of public sector corruption. These factors contributed to increasing social protests during the second half of Banzer's term.

Between January 1999 and April 2000, large-scale protests erupted in Cochabamba, Bolivia's third largest city, in response to the privatisation of water resources by foreign companies and a subsequent doubling of water prices. On 6 August 2001, Banzer resigned from office after being diagnosed with cancer. He died less than a year later. Vice President Jorge Fernando Quiroga Ramírez completed the final year of his term.

2002–2005 Sánchez de Lozada / Mesa Presidency

In the June 2002 national elections, former President Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada (MNR) placed first with 22.5% of the vote, followed by coca-advocate and native peasant-leader Evo Morales (Movement Toward Socialism, MAS) with 20.9%. A July agreement between the MNR and the fourth-place MIR, which had again been led in the election by former President Jaime Paz Zamora, virtually ensured the election of Sánchez de Lozada in the congressional run-off, and on 6 August he was sworn in for the second time. The MNR platform featured three overarching objectives: economic reactivation (and job creation), anti-corruption, and social inclusion.

In 2003 the Bolivian gas conflict broke out. On 12 October 2003 the government imposed martial law in El Alto after 16 people were shot by the police and several dozen wounded in violent clashes. Faced with the option of resigning or more bloodshed, Sánchez de Lozada offered his resignation in a letter to an emergency session of Congress. After his resignation was accepted and his vice president, Carlos Mesa, invested, he left on a commercially scheduled flight for the United States.

The country's internal situation became unfavorable for such political action on the international stage. After a resurgence of gas protests in 2005, Carlos Mesa attempted to resign in January 2005, but his offer was refused by Congress. On 22 March 2005, after weeks of new street protests from organizations accusing Mesa of bowing to U.S. corporate interests, Mesa again offered his resignation to Congress, which was accepted on 10 June. The chief justice of the Supreme Court, Eduardo Rodríguez, was sworn as interim president to succeed the outgoing Carlos Mesa.

2005–2019 Morales Presidency

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

Evo Morales won the 2005 presidential election with 53.7% of the votes in Bolivian elections.[45] On 1 May 2006, Morales announced his intent to re-nationalize Bolivian hydrocarbon assets following protests which demanded this action.[46] Fulfilling a campaign promise, on 6 August 2006, Morales opened the Bolivian Constituent Assembly to begin writing a new constitution aimed at giving more power to the indigenous majority.[47]

In August 2007, a conflict which came to be known as The Calancha Case arose in Sucre. Local citizens demanded that an official discussion of the seat of government be included in the agenda of the full body of the Bolivian Constituent Assembly. The people of Sucre wanted to make Sucre the full capital of the country, including returning the executive and legislative branches to the city, but the government rejected the demand as impractical. Three people died in the conflict and as many as 500 were wounded.[48] The result of the conflict was to include text in the constitution stating that the capital of Bolivia is officially Sucre, while leaving the executive and legislative branches in La Paz. In May 2008, Evo Morales was a signatory to the UNASUR Constitutive Treaty of the Union of South American Nations.

2009 marked the creation of a new constitution and the renaming of the country to the Plurinational State of Bolivia. The previous constitution did not allow a consecutive reelection of a president, but the new constitution allowed just for one reelection, starting the dispute if Evo Morales was enabled to run for a second term arguing he was elected under the last constitution. This also triggered a new general election in which Evo Morales was re-elected with 61.36% of the vote. His party, Movement for Socialism, also won a two-thirds majority in both houses of the National Congress.[49] By the year 2013 after being reelected under the new constitution, Evo Morales and his party attempt for a third term as President of Bolivia. The opposition argued that a third term would be unconstitutional but the Bolivian Constitutional Court ruled that Morales' first term under the previous constitution, did not count towards his term limit.[50] This allowed Evo Morales to run for a third term in 2014, and he was re-elected with 64.22% of the vote.[51] On 17 October 2015, Morales surpassed Andrés de Santa Cruz's nine years, eight months, and twenty-four days in office and became Bolivia's longest serving president.[52] During his third term, Evo Morales began to plan for a fourth, and the 2016 Bolivian constitutional referendum asked voters to override the constitution and allow Evo Morales to run for an additional term in office. Morales narrowly lost the referendum,[53] however in 2017 his party then petitioned the Bolivian Constitutional Court to override the constitution on the basis that the American Convention on Human Rights made term limits a human rights violation.[54] The Inter-American Court of Human Rights determined that term limits are not a human rights violation in 2018,[55][56] however, once again the Bolivian Constitutional Court ruled that Morales has the permission to run for a fourth term in the 2019 elections, and the permission was not retracted. "[...] the country’s highest court overruled the constitution, scrapping term limits altogether for every office. Morales can now run for a fourth term in 2019 – and for every election thereafter." described an article in The Guardian in 2017.[57]

Interim government 2019–2020

During the 2019 elections, the transmission of the unofficial quick counting process was interrupted; at the time, Morales had a lead of 46.86 percent to Mesa’s 36.72, after 95.63 percent of tally sheets were counted.[58] The Transmisión de Resultados Electorales Preliminares (TREP) is a quick count process used in Latin America as a transparency measure in electoral processes that is meant to provide a preliminary results on election day, and its shutdown without further explanation raised consternation among opposition politicians and certain election monitors.[59][60] Two days after the interruption, the official count showed Morales fractionally clearing the 10-point margin he needed to avoid a runoff election, with the final official tally counted as 47.08 percent to Mesa’s 36.51 percent.

Amidst allegations that Morales rigged the 2019 Bolivian general election, after three weeks of widespread protests organized to dispute the election, and after the head of the country's military called for his resignation,[61][62] Morales resigned on 10 November 2019.[63] The interim government was heavily protested by Morales' supporters, whose protest against Anez was met with lethal force and accusations of a massacre on indigenous pro-Morales protesters.[64] The heated divide and chain of events started after the official results were announced when the Organization of American States (OAS) as well as some local investigators and analysts had claimed irregularities and fraud,[65][66][67] but these findings were quickly heavily disputed.[68] The Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) concluded that "it is very likely that Morales won the required 10 percentage point margin to win in the first round of the election on 20 October 2019."[69] David Rosnick, an economist for CEPR, showed that "a basic coding error" was discovered in the OAS's data, and that explained OAS irreproducible findings as OAS had misused its own data when it ordered the time stamps on the tally sheets alphabetically rather than chronologically.[70] However, OAS stood by its findings arguing that "[...] researchers’ work did not address many of the allegations mentioned in the OAS report, including the accusation that Bolivian officials maintained hidden servers that could have permitted the alteration of results",[71][72] Additionally, observers from the European Union released a report with similar findings and conclusions as the OAS.[73][74] But Ethical Hacking, the audit company that was featured predominantly in OAS Report, had investigated the hidden servers and reported that no data had been altered or manipulated but those findings were omitted in OAS final report.[75][76] The tech security company hired by the TSE (under Morales) to audit the elections, also stated that there were multiple irregularities and violations of procedure and that "our function as an auditor security company is to declare everything that was found, and much of what was found supports the conclusion that the electoral process be declared null and void".[77] The New York Times reported on 7 June 2020, that the OAS analysis immediately after the 20 October election, was flawed yet fuelled “a chain of events that changed the South American nation’s history”.[78][79][80]

Morales flew to Mexico and was granted asylum there, along with his vice president and several other members of his government.[81][82] Jeanine Áñez was declared acting president of Bolivia following the constitutional line of succession after the President, Vice President and Head of the Senate. She was confirmed Interim President by the Constitutional court who declared her succession to be constitutional and automatic.[83][84] Morales, his supporters, the Governments of Mexico and Nicaragua, and other personalities argue the event as a coup d'état. International politicians, scholars and journalists are divided between describing the event as a coup or a spontaneous social uprising against an unconstitutional fourth-term.[85][86][87][88][89][90][91] Protests to reinstate Morales as President continued, and was met with violence by security forces against the indigenous supporters of Morales, after Áñez had exempted police and military from criminal responsibility in operations for "the restoration of order and public stability".[64][92]

Because the election was declared invalid, previously elected members of the House of Deputies and Senate retained their seats. This resulted in Morales' MAS party still holding a majority in both chambers.[93] New elections were scheduled for 3 May 2020.[94] In response to the Coronavirus pandemic, the Bolivian electoral body, the TSE, made an announcement postponing the election. Morales's party MAS reluctantly agreed with the first delay only. A date for the new election was delayed twice more, in the face of massive protests and violence[95][96][97] The final proposed date for the elections was the 18th of October.[98]

Official observers of the 2020 election the OAS, UNIORE and the UN all reported that they did not find any fraudulent actions in the 2020 elections.[99]

The 18 October 2020 election had a record voter turnout of 88.4% and ended in a landslide win for Morales' party taking 55.1% of the votes with a 26.3% margin over centrist former President Carlos Mesa who had 28.8% of the vote. Both Carlos Mesa and Anez conceded defeat. “I congratulate the winners and I ask them to govern thinking in Bolivia and in our democracy,” Áñez said on Twitter.[100][101]

Geography

Bolivia is located in the central zone of South America, between 57°26'–69°38'W and 9°38'–22°53'S. With an area of 1,098,581 square kilometres (424,164 sq mi), Bolivia is the world's 28th-largest country, and the fifth largest country in South America,[102] extending from the Central Andes through part of the Gran Chaco, Pantanal and as far as the Amazon. The geographic center of the country is the so-called Puerto Estrella ("Star Port") on the Río Grande, in Ñuflo de Chávez Province, Santa Cruz Department.

The geography of the country exhibits a great variety of terrain and climates. Bolivia has a high level of biodiversity, considered one of the greatest in the world, as well as several ecoregions with ecological sub-units such as the Altiplano, tropical rainforests (including Amazon rainforest), dry valleys, and the Chiquitania, which is a tropical savanna. These areas feature enormous variations in altitude, from an elevation of 6,542 metres (21,463 ft) above sea level in Nevado Sajama to nearly 70 metres (230 ft) along the Paraguay River. Although a country of great geographic diversity, Bolivia has remained a landlocked country since the War of the Pacific. Puerto Suárez, San Matías and Puerto Quijarro are located in the Bolivian Pantanal.

Bolivia can be divided into three physiographic regions:

- The Andean region in the southwest spans 28% of the national territory, extending over 307,603 square kilometres (118,766 sq mi). This area is located above 3,000 metres (9,800 ft) altitude and is located between two big Andean chains, the Cordillera Occidental ("Western Range") and the Cordillera Central ("Central Range"), with some of the highest spots in the Americas such as the Nevado Sajama, with an altitude of 6,542 metres (21,463 ft), and the Illimani, at 6,462 metres (21,201 ft). Also located in the Cordillera Central is Lake Titicaca, the highest commercially navigable lake in the world and the largest lake in South America;[103] the lake is shared with Peru. Also in this region are the Altiplano and the Salar de Uyuni, which is the largest salt flat in the world and an important source of lithium.

- The Sub-Andean region in the center and south of the country is an intermediate region between the Altiplano and the eastern llanos (plain); this region comprises 13% of the territory of Bolivia, extending over 142,815 km2 (55,141 sq mi), and encompassing the Bolivian valleys and the Yungas region. It is distinguished by its farming activities and its temperate climate.

- The Llanos region in the northeast comprises 59% of the territory, with 648,163 km2 (250,257 sq mi). It is located to the north of the Cordillera Central and extends from the Andean foothills to the Paraguay River. It is a region of flat land and small plateaus, all covered by extensive rain forests containing enormous biodiversity. The region is below 400 metres (1,300 ft) above sea level.

Bolivia has three drainage basins:

- The first is the Amazon Basin, also called the North Basin (724,000 km2 (280,000 sq mi)/66% of the territory). The rivers of this basin generally have big meanders which form lakes such as Murillo Lake in Pando Department. The main Bolivian tributary to the Amazon basin is the Mamoré River, with a length of 2,000 km (1,200 mi) running north to the confluence with the Beni River, 1,113 km (692 mi) in length and the second most important river of the country. The Beni River, along with the Madeira River, forms the main tributary of the Amazon River. From east to west, the basin is formed by other important rivers, such as the Madre de Dios River, the Orthon River, the Abuna River, the Yata River, and the Guaporé River. The most important lakes are Rogaguado Lake, Rogagua Lake, and Jara Lake.

- The second is the Río de la Plata Basin, also called the South Basin (229,500 km2 (88,600 sq mi)/21% of the territory). The tributaries in this basin are in general less abundant than the ones forming the Amazon Basin. The Rio de la Plata Basin is mainly formed by the Paraguay River, Pilcomayo River, and Bermejo River. The most important lakes are Uberaba Lake and Mandioré Lake, both located in the Bolivian marshland.

- The third basin is the Central Basin, which is an endorheic basin (145,081 square kilometres (56,016 sq mi)/13% of the territory). The Altiplano has large numbers of lakes and rivers that do not run into any ocean because they are enclosed by the Andean mountains. The most important river is the Desaguadero River, with a length of 436 km (271 mi), the longest river of the Altiplano; it begins in Lake Titicaca and then runs in a southeast direction to Poopó Lake. The basin is then formed by Lake Titicaca, Lake Poopó, the Desaguadero River, and great salt flats, including the Salar de Uyuni and Coipasa Lake.

Geology

The geology of Bolivia comprises a variety of different lithologies as well as tectonic and sedimentary environments. On a synoptic scale, geological units coincide with topographical units. Most elementally, the country is divided into a mountainous western area affected by the subduction processes in the Pacific and an eastern lowlands of stable platforms and shields.

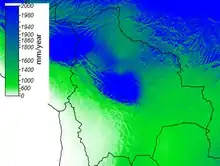

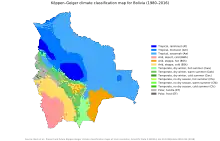

Climate

The climate of Bolivia varies drastically from one eco-region to the other, from the tropics in the eastern llanos to a polar climate in the western Andes. The summers are warm, humid in the east and dry in the west, with rains that often modify temperatures, humidity, winds, atmospheric pressure and evaporation, yielding very different climates in different areas. When the climatological phenomenon known as El Niño[106][107] takes place, it causes great alterations in the weather. Winters are very cold in the west, and it snows in the mountain ranges, while in the western regions, windy days are more common. The autumn is dry in the non-tropical regions.

- Llanos. A humid tropical climate with an average temperature of 25 °C (77 °F). The wind coming from the Amazon rainforest causes significant rainfall. In May, there is low precipitation because of dry winds, and most days have clear skies. Even so, winds from the south, called surazos, can bring cooler temperatures lasting several days.

- Altiplano. Desert-Polar climates, with strong and cold winds. The average temperature ranges from 15 to 20 °C. At night, temperatures descend drastically to slightly above 0 °C, while during the day, the weather is dry and solar radiation is high. Ground frosts occur every month, and snow is frequent.

- Valleys and Yungas. Temperate climate. The humid northeastern winds are pushed to the mountains, making this region very humid and rainy. Temperatures are cooler at higher elevations. Snow occurs at altitudes of 2,000 metres (6,600 ft).

- Chaco. Subtropical semi-arid climate. Rainy and humid in January and the rest of the year, with warm days and cold nights.

Issues with climate change

Bolivia is especially vulnerable to the negative consequences of climate change. Twenty percent of the world's tropical glaciers are located within the country,[108] and are more sensitive to change in temperature due to the tropical climate they are located in. Temperatures in the Andes increased by 0.1 °C per decade from 1939 to 1998, and more recently the rate of increase has tripled (to 0.33 °C per decade from 1980 to 2005),[109] causing glaciers to recede at an accelerated pace and create unforeseen water shortages in Andean agricultural towns. Farmers have taken to temporary city jobs when there is poor yield for their crops, while others have started permanently leaving the agricultural sector and are migrating to nearby towns for other forms of work;[110] some view these migrants as the first generation of climate refugees.[111] Cities that neighboring agricultural land, like El Alto, face the challenge of providing services to the influx of new migrants; because there is no alternative water source, the city's water source is now being constricted.

Bolivia's government and other agencies have acknowledged the need to instill new policies battling the effects of climate change. The World Bank has provided funding through the Climate Investment Funds (CIF) and are using the Pilot Program for Climate Resilience (PPCR II) to construct new irrigation systems, protect riverbanks and basins, and work on building water resources with the help of indigenous communities.[112] Bolivia has also implemented the Bolivian Strategy on Climate Change, which is based on taking action in these four areas:

- Promoting clean development in Bolivia by introducing technological changes in the agriculture, forestry, and industrial sectors, aimed to reduce GHG emissions with a positive impact on development.

- Contributing to carbon management in forests, wetlands and other managed natural ecosystems.

- Increasing effectiveness in energy supply and use to mitigate effects of GHG emissions and risk of contingencies.

- Focus on increased and efficient observations, and understanding of environmental changes in Bolivia to develop effective and timely responses.[113]

Biodiversity

Bolivia, with an enormous variety of organisms and ecosystems, is part of the "Like-Minded Megadiverse Countries".[114]

Bolivia's variable altitudes, ranging from 90–6,542 metres (295–21,463 ft) above sea level, allow for a vast biologic diversity. The territory of Bolivia comprises four types of biomes, 32 ecological regions, and 199 ecosystems. Within this geographic area there are several natural parks and reserves such as the Noel Kempff Mercado National Park, the Madidi National Park, the Tunari National Park, the Eduardo Avaroa Andean Fauna National Reserve, and the Kaa-Iya del Gran Chaco National Park and Integrated Management Natural Area, among others.

Bolivia boasts over 17,000 species of seed plants, including over 1,200 species of fern, 1,500 species of marchantiophyta and moss, and at least 800 species of fungus. In addition, there are more than 3,000 species of medicinal plants. Bolivia is considered the place of origin for such species as peppers and chili peppers, peanuts, the common beans, yucca, and several species of palm. Bolivia also naturally produces over 4,000 kinds of potatoes. The country had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 8.47/10, ranking it 21st globally out of 172 countries.[115]

Bolivia has more than 2,900 animal species, including 398 mammals, over 1,400 birds (about 14% of birds known in the world, being the sixth most diverse country in terms of bird species)[116], 204 amphibians, 277 reptiles, and 635 fish, all fresh water fish as Bolivia is a landlocked country. In addition, there are more than 3,000 types of butterfly, and more than 60 domestic animals.

In 2020 a new species of snake, the Mountain Fer-De-Lance Viper, was discovered in Bolivia.[117]

Bolivia has gained global attention for its 'Law of the Rights of Mother Earth', which accords nature the same rights as humans.[118]

Government and politics

Bolivia has been governed by democratically elected governments since 1982; prior to that, it was governed by various dictatorships. Presidents Hernán Siles Zuazo (1982–85) and Víctor Paz Estenssoro (1985–89) began a tradition of ceding power peacefully which has continued, although three presidents have stepped down in the face of popular protests: Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada in 2003, Carlos Mesa in 2005, and Evo Morales in 2019.

Bolivia's multiparty democracy has seen a wide variety of parties in the presidency and parliament, although the Revolutionary Nationalist Movement, Nationalist Democratic Action, and the Revolutionary Left Movement predominated from 1985 to 2005. On 11 November 2019, all senior governmental positions were vacated following the resignation of Evo Morales and his government. On 13 November 2019, Jeanine Áñez, a former senator representing Beni, declared herself acting President of Bolivia. Luis Arce was elected on 23 October 2020; he took office as President on 8 November 2020.

The constitution, drafted in 2006–07 and approved in 2009, provides for balanced executive, legislative, judicial, and electoral powers, as well as several levels of autonomy. The traditionally strong executive branch tends to overshadow the Congress, whose role is generally limited to debating and approving legislation initiated by the executive. The judiciary, consisting of the Supreme Court and departmental and lower courts, has long been riddled with corruption and inefficiency. Through revisions to the constitution in 1994, and subsequent laws, the government has initiated potentially far-reaching reforms in the judicial system as well as increasing decentralizing powers to departments, municipalities, and indigenous territories.

The executive branch is headed by a president and vice president, and consists of a variable number (currently, 20) of government ministries. The president is elected to a five-year term by popular vote, and governs from the Presidential Palace (popularly called the Burnt Palace, Palacio Quemado) in La Paz. In the case that no candidate receives an absolute majority of the popular vote or more than 40% of the vote with an advantage of more than 10% over the second-place finisher, a run-off is to be held among the two candidates most voted.[119]

The Asamblea Legislativa Plurinacional (Plurinational Legislative Assembly or National Congress) has two chambers. The Cámara de Diputados (Chamber of Deputies) has 130 members elected to five-year terms, 63 from single-member districts (circunscripciones), 60 by proportional representation, and seven by the minority indigenous peoples of seven departments. The Cámara de Senadores (Chamber of Senators) has 36 members (four per department). Members of the Assembly are elected to five-year terms. The body has its headquarters on the Plaza Murillo in La Paz, but also holds honorary sessions elsewhere in Bolivia. The Vice President serves as titular head of the combined Assembly.

.jpg.webp)

The judiciary consists of the Supreme Court of Justice, the Plurinational Constitutional Court, the Judiciary Council, Agrarian and Environmental Court, and District (departmental) and lower courts. In October 2011, Bolivia held its first judicial elections to choose members of the national courts by popular vote, a reform brought about by Evo Morales.

The Plurinational Electoral Organ is an independent branch of government which replaced the National Electoral Court in 2010. The branch consists of the Supreme Electoral Court, the nine Departmental Electoral Court, Electoral Judges, the anonymously selected Juries at Election Tables, and Electoral Notaries.[120] Wilfredo Ovando presides over the seven-member Supreme Electoral Court. Its operations are mandated by the Constitution and regulated by the Electoral Regime Law (Law 026, passed 2010). The Organ's first elections were the country's first judicial election in October 2011, and five municipal special elections held in 2011.

Capital

Bolivia has its constitutionally recognized capital in Sucre, while La Paz is the seat of government. La Plata (now Sucre) was proclaimed provisional capital of the newly independent Alto Perú (later, Bolivia) on 1 July 1826.[121] On 12 July 1839, President José Miguel de Velasco proclaimed a law naming the city as the capital of Bolivia, and renaming it in honor of the revolutionary leader Antonio José de Sucre.[121] The Bolivian seat of government moved to La Paz at the start of the twentieth century, as a consequence of Sucre's relative remoteness from economic activity after the decline of Potosí and its silver industry and of the Liberal Party in the War of 1899.

The 2009 Constitution assigns the role of national capital to Sucre, not referring to La Paz in the text.[119] In addition to being the constitutional capital, the Supreme Court of Bolivia is located in Sucre, making it the judicial capital. Nonetheless, the Palacio Quemado (the Presidential Palace and seat of Bolivian executive power) is located in La Paz, as are the National Congress and Plurinational Electoral Organ. La Paz thus continues to be the seat of government.

Law and crime

There are 54 prisons in Bolivia, which incarcerate around 8,700 people as of 2010. The prisons are managed by the Penitentiary Regime Directorate (Spanish: Dirección de Régimen Penintenciario). There are 17 prisons in departmental capital cities and 36 provincial prisons.[122]

Foreign relations

Despite losing its maritime coast, the so-called Litoral Department, after the War of the Pacific, Bolivia has historically maintained, as a state policy, a maritime claim to that part of Chile; the claim asks for sovereign access to the Pacific Ocean and its maritime space. The issue has also been presented before the Organization of American States; in 1979, the OAS passed the 426 Resolution,[123] which declared that the Bolivian problem is a hemispheric problem. On 4 April 1884, a truce was signed with Chile, whereby Chile gave facilities of access to Bolivian products through Antofagasta, and freed the payment of export rights in the port of Arica. In October 1904, the Treaty of Peace and Friendship was signed, and Chile agreed to build a railway between Arica and La Paz, to improve access of Bolivian products to the ports.

The Special Economical Zone for Bolivia in Ilo (ZEEBI) is a special economic area of 5 kilometres (3.1 miles) of maritime coast, and a total extension of 358 hectares (880 acres), called Mar Bolivia ("Sea Bolivia"), where Bolivia may maintain a free port near Ilo, Peru under its administration and operation[124] for a period of 99 years starting in 1992; once that time has passed, all the construction and territory revert to the Peruvian government. Since 1964, Bolivia has had its own port facilities in the Bolivian Free Port in Rosario, Argentina. This port is located on the Paraná River, which is directly connected to the Atlantic Ocean.

The dispute with Chile was taken to the International Court of Justice. The court ruled in support of the Chilean position, and declared that although Chile may have held talks about a Bolivian corridor to the sea, the country was not required to actually negotiate one or to surrender its territory.[125]

Military

The Bolivian military comprises three branches: Ejército (Army), Naval (Navy) and Fuerza Aérea (Air Force). The legal age for voluntary admissions is 18; however, when numbers are small the government in the past has recruited people as young as 14.[3] The tour of duty is generally 12 months.

The Bolivian army has around 31,500 men. There are six military regions (regiones militares—RMs) in the army. The army is organized into ten divisions. Although it is landlocked Bolivia keeps a navy. The Bolivian Naval Force (Fuerza Naval Boliviana in Spanish) is a naval force about 5,000 strong in 2008.[126] The Bolivian Air Force ('Fuerza Aérea Boliviana' or 'FAB') has nine air bases, located at La Paz, Cochabamba, Santa Cruz, Puerto Suárez, Tarija, Villamontes, Cobija, Riberalta, and Roboré.

In 2018, Bolivia signed the UN treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.[127][128]

The Bolivian government annually spends $130 million on defense.[129]

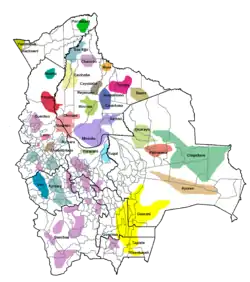

Administrative divisions

Bolivia has nine departments—Pando, La Paz, Beni, Oruro, Cochabamba, Santa Cruz, Potosí, Chuquisaca, Tarija.

According to what is established by the Bolivian Political Constitution, the Law of Autonomies and Decentralization regulates the procedure for the elaboration of Statutes of Autonomy, the transfer and distribution of direct competences between the central government and the autonomous entities.[130]

There are four levels of decentralization: Departmental government, constituted by the Departmental Assembly, with rights over the legislation of the department. The governor is chosen by universal suffrage. Municipal government, constituted by a Municipal Council, with rights over the legislation of the municipality. The mayor is chosen by universal suffrage. Regional government, formed by several provinces or municipalities of geographical continuity within a department. It is constituted by a Regional Assembly. Original indigenous government, self-governance of original indigenous people on the ancient territories where they live.

| No. | Department | Capital | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pando | Cobija |  Territorial division of Bolivia |

| 2 | La Paz | La Paz | |

| 3 | Beni | Trinidad | |

| 4 | Oruro | Oruro | |

| 5 | Cochabamba | Cochabamba | |

| 6 | Santa Cruz | Santa Cruz de la Sierra | |

| 7 | Potosí | Potosí | |

| 8 | Chuquisaca | Sucre | |

| 9 | Tarija | Tarija |

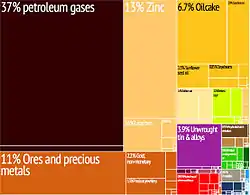

Economy

Bolivia's estimated 2012 gross domestic product (GDP) totaled $27.43 billion at official exchange rate and $56.14 billion at purchasing power parity. Despite a series of mostly political setbacks, between 2006 and 2009 the Morales administration has spurred growth higher than at any point in the preceding 30 years. The growth was accompanied by a moderate decrease in inequality.[131] Under Morales per capital GDP doubled from US$1182 in 2006 to US$2,238 in 2012. GDP growth under Morales averaged 5 percent a year, in 2014 only Panama and the Dominican Republic performed better in all of Latin America.[132] Bolivia's nominal GDP increased from 11.5 billion in 2006 to 41 billion in 2019.[133]

Bolivia in 2016 boasted the highest proportional rate of financial reserves of any nation in the world, with Bolivia’s rainy day fund totaling some US$15 billion or nearly two-thirds of total annual GDP, up from a fifth of GDP in 2005. Even the IMF was impressed by Morales' fiscal prudence.[132]

A major blow to the Bolivian economy came with a drastic fall in the price of tin during the early 1980s, which impacted one of Bolivia's main sources of income and one of its major mining industries.[134] Since 1985, the government of Bolivia has implemented a far-reaching program of macroeconomic stabilization and structural reform aimed at maintaining price stability, creating conditions for sustained growth, and alleviating scarcity. A major reform of the customs service has significantly improved transparency in this area. Parallel legislative reforms have locked into place market-liberal policies, especially in the hydrocarbon and telecommunication sectors, that have encouraged private investment. Foreign investors are accorded national treatment.[135]

.jpg.webp)

In April 2000, Hugo Banzer, the former president of Bolivia, signed a contract with Aguas del Tunari, a private consortium, to operate and improve the water supply in Bolivia's third-largest city, Cochabamba. Shortly thereafter, the company tripled the water rates in that city, an action which resulted in protests and rioting among those who could no longer afford clean water.[136][137] Amidst Bolivia's nationwide economic collapse and growing national unrest over the state of the economy, the Bolivian government was forced to withdraw the water contract.

Bolivia has the second largest natural gas reserves in South America.[138] The government has a long-term sales agreement to sell natural gas to Brazil through 2019. The government held a binding referendum in 2005 on the Hydrocarbon Law.

The US Geological Service estimates that Bolivia has 5.4 million cubic tonnes of lithium, which represent 50%–70% of world reserves. However, to mine for it would involve disturbing the country's salt flats (called Salar de Uyuni), an important natural feature which boosts tourism in the region. The government does not want to destroy this unique natural landscape to meet the rising world demand for lithium.[139] On the other hand, sustainable extraction of lithium is attempted by the government. This project is carried out by the public company "Recursos Evaporíticos" subsidiary of COMIBOL.

It is thought that due to the importance of lithium for batteries for electric vehicles and stabilization of electric grids with large proportions of intermittent renewables in the electricity mix, Bolivia could be strengthened geopolitically. However, this perspective has also been criticized for underestimating the power of economic incentives for expanded production in other parts of the world.[140]

Once Bolivia's government depended heavily on foreign assistance to finance development projects and to pay the public staff. At the end of 2002, the government owed $4.5 billion to its foreign creditors, with $1.6 billion of this amount owed to other governments and most of the balance owed to multilateral development banks. Most payments to other governments have been rescheduled on several occasions since 1987 through the Paris Club mechanism. External creditors have been willing to do this because the Bolivian government has generally achieved the monetary and fiscal targets set by IMF programs since 1987, though economic crises have undercut Bolivia's normally good record. However, by 2013 the foreign assistance is just a fraction of the government budget thanks to tax collection mainly from the profitable exports to Brazil and Argentina of natural gas.

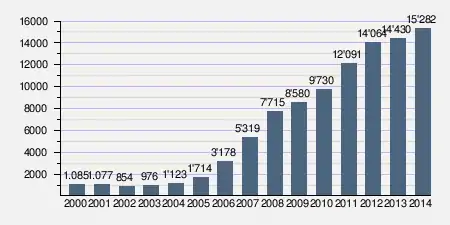

Foreign-exchange reserves

The amount in reserve currencies and gold held by Bolivia's Central Bank advanced from 1.085 billion US dollars in 2000, under Hugo Banzer Suarez's government, to 15.282 billion US dollars in 2014 under Evo Morales' government.

| Foreign-exchange reserves 2000–2014 (MM US$) [141] | |||||

| |||||

| Fuente: Banco Central de Bolivia, Gráfica elaborada por: Wikipedia. | |||||

Tourism

The income from tourism has become increasingly important. Bolivia's tourist industry has placed an emphasis on attracting ethnic diversity.[143] The most visited places include Nevado Sajama, Torotoro National Park, Madidi National Park, Tiwanaku and the city of La Paz.

The best known of the various festivals found in the country is the "Carnaval de Oruro", which was among the first 19 "Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity", as proclaimed by UNESCO in May 2001.[144]

Roads

Bolivia's Yungas Road was called the "world's most dangerous road" by the Inter-American Development Bank, called (El Camino de la Muerte) in Spanish.[145] The northern portion of the road, much of it unpaved and without guardrails, was cut into the Cordillera Oriental Mountain in the 1930s. The fall from the narrow 12 feet (3.7 m) path is as much as 2,000 feet (610 m) in some places and due to the humid weather from the Amazon there are often poor conditions like mudslides and falling rocks.[146] Each year over 25,000 bikers cycle along the 40 miles (64 km) road. In 2018, an Israeli woman was killed by a falling rock while cycling on the road.[147]

The Apolo road goes deep into La Paz. Roads in this area were originally built to allow access to mines located near Charazani. Other noteworthy roads run to Coroico, Sorata, the Zongo Valley (Illimani mountain), and along the Cochabamba highway (carretera).[148] According to researchers with the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), Bolivia's road network was still underdeveloped as of 2014. In lowland areas of Bolivia there is less than 2,000 kilometres (2,000,000 m) of paved road. There have been some recent investments; animal husbandry has expanded in Guayaramerín, which might be due to a new road connecting Guayaramerín with Trinidad.[149]

Air traffic

The General Directorate of Civil Aeronautics (Dirección General de Aeronáutica Civil—DGAC) formerly part of the FAB, administers a civil aeronautics school called the National Institute of Civil Aeronautics (Instituto Nacional de Aeronáutica Civil—INAC), and two commercial air transport services TAM and TAB.

TAM – Transporte Aéreo Militar (the Bolivian Military Airline) was an airline based in La Paz, Bolivia. It was the civilian wing of the 'Fuerza Aérea Boliviana' (the Bolivian Air Force), operating passenger services to remote towns and communities in the North and Northeast of Bolivia. TAM (a.k.a. TAM Group 71) has been a part of the FAB since 1945. The airline company has suspended its operations since 23 September 2019.[150]

Boliviana de Aviación, often referred to as simply BoA, is the flag carrier airline of Bolivia and is wholly owned by the country's government.[151]

A private airline serving regional destinations is Línea Aérea Amaszonas,[152] with services including some international destinations.

Although a civil transport airline, TAB – Transportes Aéreos Bolivianos, was created as a subsidiary company of the FAB in 1977. It is subordinate to the Air Transport Management (Gerencia de Transportes Aéreos) and is headed by an FAB general. TAB, a charter heavy cargo airline, links Bolivia with most countries of the Western Hemisphere; its inventory includes a fleet of Hercules C130 aircraft. TAB is headquartered adjacent to El Alto International Airport. TAB flies to Miami and Houston, with a stop in Panama.

The three largest, and main international airports in Bolivia are El Alto International Airport in La Paz, Viru Viru International Airport in Santa Cruz, and Jorge Wilstermann International Airport in Cochabamba. There are regional airports in other cities that connect to these three hubs.[153]

Railways

━━━ Routes with passenger traffic

━━━ Routes in usable state

·········· Unusable or dismantled routes

Bolivia possesses an extensive but aged rail system, all in 1000 mm gauge, consisting of two disconnected networks.

Technology

Bolivia owns a communications satellite which was offshored/outsourced and launched by China, named Túpac Katari 1.[154] In 2015, it was announced that electrical power advancements include a planned $300 million nuclear reactor developed by the Russian nuclear company Rosatom.[155]

Water supply and sanitation

Bolivia's drinking water and sanitation coverage has greatly improved since 1990 due to a considerable increase in sectoral investment. However, the country has the continent's lowest coverage levels and services are of low quality. Political and institutional instability have contributed to the weakening of the sector's institutions at the national and local levels.

Two concessions to foreign private companies in two of the three largest cities – Cochabamba and La Paz/El Alto – were prematurely ended in 2000 and 2006 respectively. The country's second largest city, Santa Cruz de la Sierra, manages its own water and sanitation system relatively successfully by way of cooperatives. The government of Evo Morales intends to strengthen citizen participation within the sector. Increasing coverage requires a substantial increase of investment financing.

According to the government the main problems in the sector are low access to sanitation throughout the country; low access to water in rural areas; insufficient and ineffective investments; a low visibility of community service providers; a lack of respect of indigenous customs; "technical and institutional difficulties in the design and implementation of projects"; a lack of capacity to operate and maintain infrastructure; an institutional framework that is "not consistent with the political change in the country"; "ambiguities in the social participation schemes"; a reduction in the quantity and quality of water due to climate change; pollution and a lack of integrated water resources management; and the lack of policies and programs for the reuse of wastewater.[156]

Only 27% of the population has access to improved sanitation, 80 to 88% has access to improved water sources. Coverage in urban areas is bigger than in rural ones.[157]

Demographics

| Population[158][159] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Million | ||

| 1950 | 3.1 | ||

| 2000 | 8.3 | ||

| 2018 | 11.4 | ||

According to the last two censuses carried out by the Bolivian National Statistics Institute (Instituto Nacional de Estadística, INE), the population increased from 8,274,325 (from which 4,123,850 were men and 4,150,475 were women) in 2001 to 10,059,856 in 2012.[160]

In the last fifty years the Bolivian population has tripled, reaching a population growth rate of 2.25%. The growth of the population in the inter-census periods (1950–1976 and 1976–1992) was approximately 2.05%, while between the last period, 1992–2001, it reached 2.74% annually.

Some 67.49% of Bolivians live in urban areas, while the remaining 32.51% in rural areas. The most part of the population (70%) is concentrated in the departments of La Paz, Santa Cruz and Cochabamba. In the Andean Altiplano region the departments of La Paz and Oruro hold the largest percentage of population, in the valley region the largest percentage is held by the departments of Cochabamba and Chuquisaca, while in the Llanos region by Santa Cruz and Beni. At national level, the population density is 8.49, with variations marked between 0.8 (Pando Department) and 26.2 (Cochabamba Department).

The largest population center is located in the so-called "central axis" and in the Llanos region. Bolivia has a young population. According to the 2011 census, 59% of the population is between 15 and 59 years old, 39% is less than 15 years old. Almost 60% of the population is younger than 25 years of age.

Genetics

According to a genetic study done on Bolivians, average values of Native American, European and African ancestry are 86%, 12.5%, and 1.5%, in individuals from La Paz and 76.8%, 21.4%, and 1.8% in individuals from Chuquisaca; respectively.[161]

Ethnic and racial classifications

_-_Bolivia-133.jpg.webp)

The vast majority of Bolivians are mestizo (with the indigenous component higher than the European one), although the government has not included the cultural self-identification "mestizo" in the November 2012 census.[162] There are approximately three dozen native groups totaling approximately half of the Bolivian population – the largest proportion of indigenous people in Latin America. Exact numbers vary based on the wording of the ethnicity question and the available response choices. For example, the 2001 census did not provide the racial category "mestizo" as a response choice, resulting in a much higher proportion of respondents identifying themselves as belonging to one of the available indigenous ethnicity choices. Mestizos are distributed throughout the entire country and make up 26% of the Bolivian population, with the predominantly mestizo departments being Beni, Santa Cruz, and Tarija. Most people assume their mestizo identity while at the same time identifying themselves with one or more indigenous cultures. A 2018 estimate of racial classification put mestizo (mixed white and Amerindian) at 68%, indigenous at 20%, white at 5%, cholo at 2%, black at 1%, other at 4%, while 2% were unspecified; 44% attributed themselves to some indigenous group, predominantly the linguistic categories of Quechuas or Aymaras.[3] Whites comprised about 14% of the population in 2006, and are usually concentrated in the largest cities: La Paz, Santa Cruz de la Sierra and Cochabamba, but as well in some minor cities like Tarija and Sucre. The ancestry of Whites and the White ancestry of Mestizos lies within the continents of Europe and Middle East, most notably Spain, Italy, Germany, Croatia, Lebanon and Syria. In the Santa Cruz Department, there are several dozen colonies of German-speaking Mennonites from Russia totaling around 40,000 inhabitants (as of 2012).[163]

Afro-Bolivians, descendants of African slaves who arrived in the time of the Spanish Empire, inhabit the department of La Paz, and are located mainly in the provinces of Nor Yungas and Sud Yungas. Slavery was abolished in Bolivia in 1831.[164] There are also important communities of Japanese (14,000[165]) and Lebanese (12,900[166]).

Indigenous peoples, also called "originarios" ("native" or "original") and less frequently, Amerindians, could be categorized by geographic area, such as Andean, like the Aymaras and Quechuas (who formed the ancient Inca Empire), who are concentrated in the western departments of La Paz, Potosí, Oruro, Cochabamba and Chuquisaca. There also are ethnic populations in the east, composed of the Chiquitano, Chané, Guaraní and Moxos, among others, who inhabit the departments of Santa Cruz, Beni, Tarija and Pando.

There are small numbers of European citizens from Germany, France, Italy and Portugal, as well as from other countries of the Americas, as Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Cuba, Ecuador, the United States, Paraguay, Peru, Mexico and Venezuela, among others. There are important Peruvian colonies in La Paz, El Alto and Santa Cruz de la Sierra.

There are around 140,000 mennonites in Bolivia of Friesian, Flemish and German ethnic origins.[167][168]

Indigenous peoples

The Indigenous peoples of Bolivia can be divided into two categories of ethnic groups: the Andeans, who are located in the Andean Altiplano and the valley region; and the lowland groups, who inhabit the warm regions of central and eastern Bolivia, including the valleys of Cochabamba Department, the Amazon Basin areas of northern La Paz Department, and the lowland departments of Beni, Pando, Santa Cruz, and Tarija (including the Gran Chaco region in the southeast of the country). Large numbers of Andean peoples have also migrated to form Quechua, Aymara, and intercultural communities in the lowlands.

- Andean ethnicities

- Aymara people. They live on the high plateau of the departments of La Paz, Oruro and Potosí, as well as some small regions near the tropical flatlands.

- Quechua people. They mostly inhabit the valleys in Cochabamba and Chuquisaca. They also inhabit some mountain regions in Potosí and Oruro. They divide themselves into different Quechua nations, as the Tarabucos, Ucumaris, Chalchas, Chaquies, Yralipes, Tirinas, among others.

- Uru people

- Ethnicities of the Eastern Lowlands

- Guaraníes: made up of Guarayos, Pausernas, Sirionós, Chiriguanos, Wichí, Chulipis, Taipetes, Tobas, and Yuquis.

- Tacanas: made up of Lecos, Chimanes, Araonas, and Maropas.

- Panos: made up of Chacobos, Caripunas, Sinabos, Capuibos, and Guacanaguas.

- Aruacos: made up of Apolistas, Baures, Moxos, Chané, Movimas, Cayabayas, Carabecas, and Paiconecas (Paucanacas).

- Chapacuras: made up of Itenez (More), Chapacuras, Sansinonianos, Canichanas, Itonamas, Yuracares, Guatoses, and Chiquitanos.

- Botocudos: made up of Bororos and Otuquis.

- Zamucos: made up of Ayoreos.

Language

Bolivia has great linguistic diversity as a result of its multiculturalism. The Constitution of Bolivia recognizes 36 official languages besides Spanish: Aymara, Araona, Baure, Bésiro, Canichana, Cavineño, Cayubaba, Chácobo, Chimán, Ese Ejja, Guaraní, Guarasu'we, Guarayu, Itonama, Leco, Machajuyai-Kallawaya, Machineri, Maropa, Mojeño-Ignaciano, Mojeño-Trinitario, Moré, Mosetén, Movima, Pacawara, Puquina, Quechua, Sirionó, Tacana, Tapieté, Toromona, Uru-Chipaya, Weenhayek, Yaminawa, Yuki, Yuracaré, and Zamuco.[2]

Spanish is the most spoken official language in the country, according to the 2001 census; as it is spoken by two-thirds of the population. All legal and official documents issued by the State, including the Constitution, the main private and public institutions, the media, and commercial activities, are in Spanish.

The main indigenous languages are: Quechua (21.2% of the population in the 2001 census), Aymara (14.6%), Guarani (0.6%) and others (0.4%) including the Moxos in the department of Beni.[3]

Plautdietsch, a German dialect, is spoken by about 70,000 Mennonites in Santa Cruz. Portuguese is spoken mainly in the areas close to Brazil.

Bilingual education was implemented in Bolivia under the leadership of President Evo Morales. His program placed emphasis on the expansion of indigenous languages in the educational systems of the country.[169]

Religion

Bolivia is a constitutionally secular state that guarantees the freedom of religion and the independence of government from religion.[171]

According to the 2001 census conducted by the National Institute of Statistics of Bolivia, 78% of the population is Roman Catholic, followed by 19% that are Protestant, as well as a small number of Bolivians that are Orthodox, and 3% non-religious.[172][173]

The Association of Religion Data Archives (relying on the World Christian Database) records that in 2010, 92.5% of Bolivians identified as Christian (of any denomination), 3.1% identified with indigenous religion, 2.2% identified as Baháʼí, 1.9% identified as agnostic, and all other groups constituted 0.1% or less.[174]

Much of the indigenous population adheres to different traditional beliefs marked by inculturation or syncretisim with Christianity. The cult of Pachamama,[175] or "Mother Earth", is notable. The veneration of the Virgin of Copacabana, Virgin of Urkupiña and Virgin of Socavón, is also an important feature of Christian pilgrimage. There also are important Aymaran communities near Lake Titicaca that have a strong devotion to James the Apostle.[176] Deities worshiped in Bolivia include Ekeko, the Aymaran god of abundance and prosperity, whose day is celebrated every 24 January, and Tupá, a god of the Guaraní people.

Largest cities and towns

Approximately 67% of Bolivians live in urban areas,[177] among the lowest proportion in South America. Nevertheless, the rate of urbanization is growing steadily, at around 2.5% annually. According to the 2012 census, there are total of 3,158,691 households in Bolivia – an increase of 887,960 from 2001.[160] In 2009, 75.4% of homes were classified as a house, hut, or Pahuichi; 3.3% were apartments; 21.1% were rental residences; and 0.1% were mobile homes.[178] Most of the country's largest cities are located in the highlands of the west and central regions.

| Rank | Name | Department | Pop. | Rank | Name | Department | Pop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Santa Cruz de la Sierra  El Alto |

1 | Santa Cruz de la Sierra | Santa Cruz | 1,453,549 | 11 | Montero | Santa Cruz | 109,518 |  La Paz  Cochabamba |

| 2 | El Alto | La Paz | 848,840 | 12 | Trinidad | Beni | 106,422 | ||

| 3 | La Paz | La Paz | 764,617 | 13 | Warnes | Santa Cruz | 96,406 | ||

| 4 | Cochabamba | Cochabamba | 630,587 | 14 | Yacuíba | Tarija | 91,998 | ||

| 5 | Oruro | Oruro | 264,683 | 15 | La Guardia | Santa Cruz | 89,080 | ||

| 6 | Sucre | Chuquisaca | 259,388 | 16 | Riberalta | Beni | 89,003 | ||

| 7 | Tarija | Tarija | 205,346 | 17 | Viacha | La Paz | 80,388 | ||

| 8 | Potosí | Potosí | 189,652 | 18 | Villa Tunari | Cochabamba | 72,623 | ||

| 9 | Sacaba | Cochabamba | 169,494 | 19 | Cobija | Pando | 55,692 | ||

| 10 | Quillacollo | Cochabamba | 137,029 | 20 | Tiquipaya | Cochabamba | 53,062 | ||

Culture

Bolivian culture has been heavily influenced by the Aymara, the Quechua, as well as the popular cultures of Latin America as a whole.

The cultural development is divided into three distinct periods: precolumbian, colonial, and republican. Important archaeological ruins, gold and silver ornaments, stone monuments, ceramics, and weavings remain from several important pre-Columbian cultures. Major ruins include Tiwanaku, El Fuerte de Samaipata, Inkallaqta and Iskanawaya. The country abounds in other sites that are difficult to reach and have seen little archaeological exploration.[180]