Booster engine

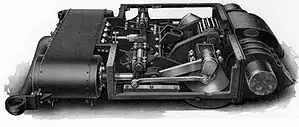

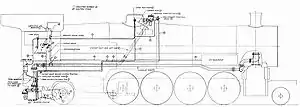

A booster engine for steam locomotives is a small two-cylinder steam engine back-gear-connected to the trailing truck axle on the locomotive or the lead truck on the tender. A rocking idler gear permits it to be put into operation by the driver (engineer). It drives one axle only and can be non-reversible, with one idler gear, or reversible, with two idler gears.

A booster engine is used to start a heavy train or maintain low speed under demanding conditions. Rated at about 300 horsepower (220 kW) at speeds of from 10 to 30 mph (16 to 48 km/h), it can be cut in while moving at speeds under 12–20 miles per hour (19–32 km/h) and is semi-automatically cut out via the engineer notching back the reverse gear between 20 and 35 mph (32 and 56 km/h), depending on the model and design of the booster. A tractive effort of 10,000–12,000 pounds-force (44–53 kN) is common, although ratings of up to around 15,000 lbf (67 kN) were possible.

Tender boosters are equipped with side-rods connecting axles on the lead truck. Such small side-rods restrict speed and are therefore confined to switching locomotives, often used in transfer services between yards. Tender boosters were far more rare than engine boosters.

Reasons for booster use

The booster is intended to make up for fundamental flaws in the design of the standard steam locomotive. First, most steam locomotives do not provide power to all wheels. The amount of force that can be applied to the rail depends on the weight on the driven wheels and the factor of adhesion of the wheels against the track. Unpowered wheels are generally needed to provide stability at speed, but at low speed they are not required, so they effectively 'waste' weight which could be used for traction.

Second, the "gearing" of a steam locomotive is constant, because the pistons are linked directly to the wheels via rods and cranks. Therefore, a compromise must be struck between ability to haul at low speed and the ability to run fast without inducing excessive piston speeds (which would cause failure), or the exhaustion of steam. That compromise means that, at low speeds, a steam locomotive is not able to use all the power the boiler is capable of producing; it simply cannot use steam that quickly, so there is a big difference between the amount of steam the boiler can produce and the amount that can be used. The booster engine enables that wasted potential to be put to use.

Disadvantages

Boosters are costly to maintain, with their flexible steam and exhaust pipes, idler gear, etc. Improper operation could also result in undesirable drops in boiler pressure and/or damage to the booster.

Usage

North America

The booster saw most use in North America. Railway systems elsewhere often considered the expense and complexity unjustified.

Even in the North American region, booster engines were applied to only a fraction of all locomotives built. Some railroads used boosters extensively while others did not. The New York Central was a fan of booster engines and applied them to all of its 4-6-4 Hudson locomotives. The rival Pennsylvania Railroad, however, used few booster-equipped locomotives.

Canadian Pacific Railway rostered 3,257 steam locomotives acquired between 1881 and 1949, yet only 55 were equipped with boosters. 17 H1 class 4-6-4s, 2 K1 class 4-8-4s and all 36 T1 class 2-10-4s.

Australia

In Australia, Victorian Railways equipped all but one of its X class 2-8-2 locomotives (built between 1929 and 1947) with a 'Franklin' two-cylinder booster engine, following a successful trial of the device on a smaller N class 2-8-2 in 1927. From 1929 onwards, South Australian Railways 500 class 4-8-2 heavy passenger locomotives were rebuilt into 4-8-4s with the addition of a booster truck .

New Zealand

NZR's Kb class of 1939 were built with a booster truck to enable the locomotives to handle the steeper grades of some South Island lines (particularly the Cass Bank of the Midland Line). Some boosters were later removed because of the gear jamming.

Great Britain

In Great Britain, eight locomotives of four different classes on the London and North Eastern Railway were equipped with booster units by Nigel Gresley. Four were existing locomotives rebuilt with boosters between 1923 and 1932: one of class C1 (in 1923);[1] both of the conversions from class C7 to class C9 (in 1931);[2] and one of class S1 (in 1932).[3] The remaining four were all fitted to new locomotives: the two P1 2-8-2 locomotives, built in 1925;[4] and two class S1 locomotives built in 1932.[3] The boosters were removed between 1935 and 1938,[5][6] apart from those on class S1 which were retained until 1943.[3]

An early type of booster used in Great Britain was the steam tender, which was tried in 1859 by Benjamin Connor of the Caledonian Railway on four 2-4-0 locomotives. Archibald Sturrock of the Great Northern Railway (GNR) patented a similar system on 6 May 1863 (patent no. 1135). It was used on fifty GNR 0-6-0 locomotives: thirty converted from existing locomotives between 1863 and 1866, and twenty built new in 1865 (nos. 400–419). The equipment was removed from all fifty during 1867–68.[7][8]

References

- Boddy, M.G.; Brown, W.A.; Fry, E.V.; Hennigan, W.; Hoole, Ken; Manners, F.; Neve, E.; Platt, E.N.T.; Russell, O.; Yeadon, W.B. (November 1979). Fry, E.V. (ed.). Locomotives of the L.N.E.R., part 3A: Tender Engines - Classes C1 to C11. Kenilworth: RCTS. p. 26. ISBN 0-901115-45-2.

- Boddy et al. 1979, p. 122

- Boddy, M.G.; Brown, W.A.; Fry, E.V.; Hennigan, W.; Hoole, Ken; Manners, F.; Neve, E.; Platt, E.N.T.; Proud, P.; Yeadon, W.B. (June 1977). Fry, E.V. (ed.). Locomotives of the L.N.E.R., part 9B: Tank Engines - Classes Q1 to Z5. Kenilworth: RCTS. p. 24. ISBN 0-901115-41-X.

- Boddy, M.G.; Brown, W.A.; Neve, E.; Yeadon, W.B. (November 1983). Fry, E.V. (ed.). Locomotives of the L.N.E.R., part 6B: Tender Engines - Classes O1 to P2. Kenilworth: RCTS. p. 153. ISBN 0-901115-54-1.

- Boddy et al. 1979, pp. 29, 126

- Boddy et al. 1983, p. 157

- "Great Northern Railway locomotives: Bury, Sturrock & Stirling designs". Steamindex.com. Retrieved 2012-06-16.

- Groves, Norman (1986). Great Northern Locomotive History: Volume 1 1847-66. RCTS. pp. 73–74, 83, 105, 109, 111. ISBN 0-901115-61-4.

Further reading

- Bruce, Alfred W. (1952). The Steam Locomotive in America. Bonanza Books, New York.

- Railway Master Mechanics' Association (1922). Locomotive Cyclopedia of American Practice, Sixth Edition—1922. Simmons-Boardman.

- Franklin Type C2 Booster Engine

- Talbot, Fred. A (1923), "The locomotive "booster"", Railways of the World, pp. 84–91 illustrated description of the booster engine