Boudinot Currie Atterbury

Boudinot Currie Atterbury (1852–1930), from a wealthy New York family, trained to be a medical doctor and worked with the Presbyterian missions in China and later with Chinese communities in the USA.

He attended Phillips Academy class of 1869 before going to Yale, leaving as a non-graduate in 1873.[1] After three years work experience he attended medical school at Bellevue Hospital from where he graduated with a medical degree in 1878. He expanded his medical knowledge, working in New York, Paris and Palestine before moving to China as a medical missionary in 1879. He built a hospital in Peking with funding from family and friends, treating the poor and training Chinese medical students.[2] In 1890 he married Mary Josephine Lowrie (1858-1910), the daughter of missionaries (Amelia and Reuben Post Lowrie)[3] who had lived and worked in China. In 1896 he was awarded the Order of the Double Dragon by the Dowager Empress for his services during the First Sino-Japanese War of 1894.

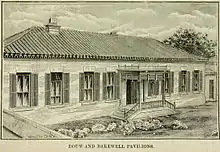

In 1894 Atterbury attended the medical mission at Pao-ting-fu whilst the resident doctor took leave. During his tenure he built, at his own expense, a dispensary and additional hospital rooms. He also donated funds at a later date for equipment to the hospital.[4]

Due to ill health he left China in about 1898 and did not return, but continued his work amongst the Chinese population in Pasadena, Los Angeles and Brooklyn. In 1900 several of his colleagues in China were killed during the Boxer uprising.[5][6]

Atterbury’s wife Josephine died in Pasadena in 1910 and he died on 21 May 1930 in Altamonte Springs, Florida. Their daughter Daisy (Marguerite) returned to China to continue the missionary work and was interned in the Japanese Weihsien Compound during WWII (repatriated 1943).[7] While their son Boudinot Bakewell Atterbury went on to have a successful business career and chose not to carry out missionary work.[8]

Family

Atterbury was born in Manchester, England on 10 June 1852. His ancestors included Bishop Atterbury and Elias Boudinot. His father, Benjamin Bakewell Atterbury, was a New York merchant with a shipping agency in Manchester who in 1847 married Olivia Phelps, daughter of Anson Greene Phelps and Olivia Egleston. Boudinot Atterbury’s uncles included James Boulter Stokes, Daniel James, Charles F. Pond and William Earle Dodge, wealthy families that supported and funded his missionary work in China.[9] His brother and one of his sisters married into the Van Rensselaer family who had relatives working in China (some of whom were killed in the Boxer uprising). Another of his sponsors was Deborah Matilda Douw, who was also related via the Van Rensselaer connection. She survived the uprising by disguising herself in traditional Chinese clothing.[10] Douw had funded a pavilion for female patients at the hospital and paid for a female physician for the facility.

References

- Shepard, Frederick J. "History of Yale Class of 1873". Internet Archive. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- Atterbury, Boudinot (1886). Pekin Hospital, Pekin China. Presbyterian Mission. p. Cover. Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- Johnson, Rossiter (1904). The twentieth century biographical dictionary of notable Americans: Lowrie, Reuben Post. Retrieved 19 November 2014.

- Taylor Memorial Hospital. Presbyterian Mission Paotingfu. 1920. p. 4. Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- "American Presbyterian Missionaries Killed During 1900 in the Boxer Rebellion". Presbyterian Heritage Center. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- Ketler, Isaac (1902). The Tragedy of Paotingfu. Fleming H Revell. Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- "Chinese War Film Shown". Google News. The Pittsburgh Press - Aug 24, 1938. Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- Leighton, David (2 November 2020). "Street Smarts: Atterbury's winding road to Tucson started in China". Arizona Daily Star. Retrieved 3 November 2020.

- Atterbury, Boudinot (1886). Pekin Hospital Pekin China. Presbyterian Mission. p. Inside end cover. Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- "Missionary Leaves $50,000 to charities" (PDF). New York Times. 4 January 1912. Retrieved 18 November 2014.