Breach at Cucca

The so-called breach at Cucca (Italian: rotta della Cucca) traditionally refers to a flood in the Veneto region of Italy that should have happened on October 17, 589[1] according to the chronicles of Paul the Deacon. The Adige river overflowed after a "deluge of water that is believed not to have happened after the time of Noah";[1] the flood caused great loss of lives, and destroyed part of the city walls of Verona as well as paths, roads and large part of the country in lower Veneto.[1]

.jpg.webp)

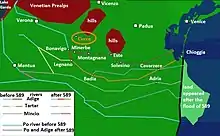

The tradition asserts that a breach opened in the banks of the Adige at Cucca, nowadays Veronella, about 35 km SE of Verona.[2]

Contemporary historians think that the breach never really happened, and the tradition simply refers to the disasters due to the lack of maintainment of the streams that followed the fall of the Roman Empire. The Lombards did not repair the banks, and the waters of the Adige had been let free to flow through the lower Veneto for centuries,[2] in order to set a swamp on the borders with the Exarchate of Ravenna.

This point of view should be balanced against the worldwide disastrous climate changes of 535-536. Even though the dates do not exactly align, it is a fact that in that century there was at least "one year without summer", it is conceivable that the exceptionally bad weather conditions reported worldwide for that unknown year, whose consequences included skipped harvests and famine in places as far apart as Ireland, Scandinavia and China, constitute the real background also for this reported climate disaster.

Consequences

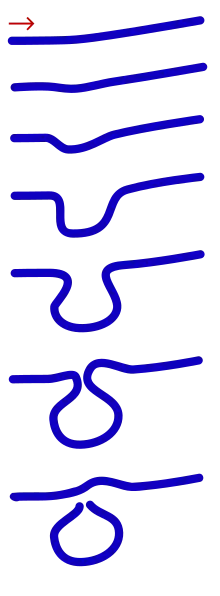

The hydrography of the lower Veneto had a dramatic change after the breach at Cucca: the river Adige did no more pass through Montagnana and Este and diverted to the south passing through Legnago;[2] centuries later, as the land dried up, it started following what had been the former course of the Chirola canal, passing through Badia Polesine and Cavarzere.

The Tartaro river contributed to the swamp;[2] as the land dried up, some villages started to be set around its course: they were the first hamlets of Lendinara, Villanova del Ghebbo, Rovigo and Villadose.

The Mincio river diverted to the south and has become a tributary of the Po river since then; it had been a waterway from the Adriatic Sea to the lake Garda until then.[2] The loss of this last significance contributed to the definitive decline of Adria and its port.[2]

The former lower course of the Mincio, that flowed into the Adriatic Sea by Adria, was still connected to the Tartaro.

The flooding, along with the subsequent capture by the Lombards of the city of Padua in 601, led to the movement of crowds of refugees into the Venetian Lagoon, whose population explosively increased, which led to the creation of the Venetian state.

Notes

- Paul the Deacon. Historia Langobardorum (in Latin). pp. Liber III, 23.

- Zemella, Rubis (1998) [1992]. La mia Polesella perduta (in Italian). A.V.I.S. di Polesella.