Bridge of Ashes

Bridge of Ashes is an experimental[1] science fiction novel by author Roger Zelazny.[2] The paperback edition was published in 1976 and the hardcover in 1979. Zelazny describes the book as one of five books from which he learned things “that have borne me through thirty or so others.”[1] He states that he “felt that if I could pull it off I could achieve some powerful effects. What I learned from this book is something of the limits of puzzlement in that no man’s land between suspense and the weakening of communication.”[1]

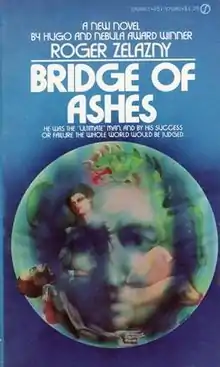

Cover of first edition (paperback) | |

| Author | Roger Zelazny |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Gene Szafran |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Science fiction |

| Published | 1976 Signet/New American Library |

| Media type | |

| Pages | 154 |

| ISBN | 0-451-15561-0 |

| OCLC | 2409402 |

| 813/.5/4 | |

| LC Class | PS3576.E43 B74 1976 |

Plot

Alien invaders manipulate humans for millennia in order to create the “post-ecological-catastrophe environment”[3] that is their natural habitat. Because of pollution the self-destruction of the human race is imminent. Dennis Guise is a 13-year-old boy who is the most powerful telepath in the world. However, due to the sheer volume of thoughts that he inadvertently receives from others, he is catatonic. He sometimes takes on whole personalities, often famous people, living or dead. Through therapy he eliminates these people from his mind and learns to block the experiential input of others. He is then able to be his own person. He decides to help a mysterious figure called “the dark man” convince the aliens to leave Earth, and they are successful.

Setting

The setting is in the “near-future Earth.”[4] The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction defines the “near future” as an “imprecise term used to identify novels set just far enough in the future to allow for certain technological or social changes without being so different that it is necessary to explain that society to the reader.”[5] The near future of Bridge includes telepaths, aliens, alien ships, a mysterious long-lived “the dark man,” and the occupation of the moon. Otherwise, features of the world are like those of 1976, the year Bridge was written. Locations in the book include the Southwestern United States, the moon, and parts of Africa.

Principal Characters

- Dennis Guise – The most powerful telepath in history is catatonic as a child because of his perception of the overpowering thoughts and experiences of others, but obtains his own individuality through therapy administered on the moon.

- Richard Guise – Dennis’ father is also a telepath and the President of the International Telepathic Operators Union.

- Victoria Guise – Dennis’ mother, another telepath, sometimes strongly disagrees with her husband over Dennis’ course of treatment.

- Dr. Winchell – A psychiatrist diagnoses Dennis and recommends a psychiatrist to treat him.

- Lydia Dimanche – Dennis’ first psychiatrist is a mysterious figure with connections to the Children of Earth and the dark man.

- Children of Earth (COE) – An eco-terrorist group seeks to minimize the pollution of the planet through selective assassination and other means.

- Quick Smith – A member of the Children of the Earth serves Lydia Dimanche and indirectly the dark man.

- the dark man – A man older than history and with the ability to slow time fights the aliens.

- the aliens – A group of aliens guides humankind towards the ecological destruction of the planet and itself.

- Roderick Leishman – Dennis channels this COE assassin.

- Alec Stern – A therapist on the moon is successful in Dennis’ treatment.

Literary discussion

Prose

Zelazny has been repeatedly referred to as a prose-poet.[6][7][8] However, there does not appear to be agreement about the true nature of his prose.

Richard Geis refers to "the Zelazny magic; that indefinable stylistic touch that makes him extremely readable."[9] His prose in has been variously described as "straight-forward,"[10] "well-written and fast paced," "colloquial and functional."[11]Theodore Sturgeon praises him for his "texture, cadence and pace."[12]

Richard Cowper writes that Zelazny

has fashioned for himself a style which . . . is designed to dazzle. Seen at its best, . . . it is allusive, economical, picturesque and witty [and] highly metaphorical. There are felicities of style, of invention of learning or wit, which stamp it as being his own.[13]

Poetry

As a poet Zelazny uses in his novels poetic elements such as form, image, structure, alliteration, internal rhyme and metaphor.[14][15][16] The following is a good example of this style from Bridge of Ashes:

And of self the—

—to old be. Was the—

. . . Man by the seaside. See—

. . . Drawing is the man in the damp sand. Power. His eye the binder of angles. His I—

Opposite and adjacent, of course; gentle and unnoticed, as he scribes the circle. Where the line cuts them. At hand, the sea forms green steps and trellises, gentle, beneath the warm blue sky.[17]

Protagonists

Theodore Krulik, one of Zelazny’s literary biographers, has indicated that Zelazny’s protagonists are all cast from a certain mold:

More than most writers, Zelazny persists in reworking a persona composed of a single literary vision. This vision is the unraveling of a complex personality with special abilities, intelligent, cultured, experienced in many areas, but who is fallible, needing emotional maturity, and who candidly reflects upon the losses in his life. This complex persona cuts across all of Zelazny’s writings. . . .[18]

Jane Lindskold takes a different view and notes that Zelazny also has protagonists that are ordinary people “who (are) forced into action by extraordinary circumstances.”[19]

Dennis Guise fits neither mold exactly. Krulik’s criteria fit in some ways. At the beginning of the story, Dennis is catatonic because of the confusion of the telepathic inputs from so many people. Through the various personalities that he channels he may gain a certain, if incomplete, culture and experience. He needs emotional maturity, his intelligence is assumed by some, but it is unclear that he realizes his losses from his years of catatonia.

Reception

Chris Lambton in Thrust, SF in Review states baldly that Bridge is Zelazny’s worst novel. He writes that Zelazny at his best “soars,” “sings,” and “glistens,” but in Bridge he is “tepid, uninspired and repetitive.” He goes on to write “This is a readable, serviceable, flawed novel, what is generally termed a yeomenlike performance.” He notes that “In comparison with his best work, this seems anemic,” and “The humor that fueled all of Zelazny’s previous work is not here. . . .” [20] Susan Wood in Delap’s F and SF Review characterizes the novel as “slight.” She writes further: "The potential focus of the book, Dennis Guise’s own reactions, are never really explored. Instead, a fascinating idea and characterization is subordinated to a Laser-book action formula: keep the plot moving, tie it up quickly, toss the book away."[21] In Analog Science Fiction and Fact Lester del Rey wonders if Zelazny considers “form and presentation above structure and content.”[22] He summarizes his review: “It’s interesting, and some of the writing and ideas are excellent. But don’t expect to be greatly satisfied at the end.” [23]

In a review in Foundation: The International Review of Science Fiction Brian M. Stableford asserts that Bridge is an “incomplete” novel: "Here, all together, we have beginning, middle and end (albeit mixed up a little), but all three are cut to the bone, revealing plot and structure but hardly anything of flesh, with virtually no connective tissue."[24] He characterizes Zelazny’s literary techniques as “flashy and aggressive.” These techniques allow “him to cut abruptly from scene to scene, building dazzling images and maintaining a furious pace. It makes his writing tremendously vigorous, and it makes reading him an exciting business.” However, the “fragmentary nature of the stories” permits him to make Bridge’s story “ridiculous” and “facile.”[25]

Spider Robinson in Analog Science Fiction and Fact calls Bridge’s climax “so subdued that it would fail to register on the most sensitive seismograph ever built, a stifled sneeze of a showdown after which Guise (and you) must be told that the battle is over and he has won.” He goes on to write: "I always enjoy reading Zelazny; his words chase each other fluidly and fluently. His theory of exactly how the aliens created mankind is ingenious and, I think, original. But I’d have to describe this book as a misshapen thing with many features of interest."[26]

Publication history

- Zelazny, Roger (1976). Bridge of Ashes. Signet/New American Library. pp. 154. Paperback. ISBN 0-451-15561-0.

- Zelazny, Roger (1976). Bridge of Ashes. Roc. pp. 154. Paperback. ISBN 0-451-13550-4.

- Zelazny, Roger (1977). Kinderen van de Aarde. Het Spectrum. pp. 153. Paperback. ISBN 90-274-0942-0.

- Zelazny, Roger (1979). Bridge of Ashes. Gregg Press. pp. 154. Hardcover. ISBN 0-8398-2466-1.

- Zelazny, Roger (1981). Un Pont de Cendres. Presses Pocket. pp. 190. Paperback. ISBN 2-266-00974-5.

- Zelazny, Roger (1981). Today We Choose Faces/Bridge of Ashes. Signet/New American Library. pp. 174+154. ISBN 0-451-09989-3.

- Zelazny, Roger (1989). Bridge of Ashes with Foreword. Signet/New American Library. pp. 154. Paperback. ISBN 0-451-15561-0.

- Zelazny, Roger (2011). Kinderen van de Aarde. Het Spectrum. pp. 153. Paperback. ISBN 978-90-315-0338-4.

Notes

- Zelazny 1989, p ii

- "Roger Zelazny". Worlds without End. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- Zelazny 1989, p. 18

- Wood, January 1976, p. 7

- D’Ammassa 2005, p. 436

- Lindskold 1993, p. 76

- Cowper March 1977, p.143

- Sturgeon 1967, p. 5

- Geis February 1976, p. 23

- Budrys July 1977, p. 5

- Wood January 1976, p. 5

- Sturgeon 1967, p. 7

- Cowper March 1977, pp. 146-147

- Lindskold 1993, pp 118–119

- Sturgeon 1967, p 5

- Cowper March 1977, p 143

- Zelazny 1987, p 73

- Krulik 1986, pp 23–24

- Lindskold 1993, p 113

- Lambton 1977, p. 35

- Wood 1977, p. 36

- del Rey 1977, p.172

- del Rey 1977, p.173

- Stableford 1977, p. 149

- Stableford 1977, pp. 149-150

- Robinson 1981, p. 160

References

- Budrys, Algis (July 1977). "Books". The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction.

- Cowper, Richard (March 1977). "A Rose Is a Rose Is a Rose. . .In Search of Roger Zelazny". Foundation - The International Review of Science Fiction. The Science Fiction Foundation. 11 and 12: 145–147.

- D'Ammassa, Don (2005). "Roger Zelazny". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. New York: Facts On File, Inc. pp. 432–434. ISBN 0-8160-5924-1.

- del Rey, Lester (1977). "The Reference Library". Analog Science Fiction and Fact. XCII (1): 172–173.

- Geis, Richard E. (February 1976). "Prozine Notes". Science Fiction Review. 5.

- Krulik, Theodore (1986). Roger Zelazny. New York: Ungar Publishing. ISBN 0-8044-2490-X.

- Lambton, Chris (Spring 1977). "Book Reviews". Thrust, SF in Review (8): 35.

- Lindskold, Jane M. (1993). Roger Zelazny. New York: Twayne Publishers. ISBN 0-8057-3953-X.

- Robinson, Spider (1981). "The Reference Library". Analog Science Fiction and Science Fact. CI (7): 180.

- Stableford, Brian M. (1977). "review section (no. 12)". Foundation - The International Review of Science Fiction. 12: 149–150.

- Sturgeon, Theodore (1967). "Introduction". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) In Zelazny, Roger (1967). Four for Tomorrow. New York: Ace. ISBN 9780824014445. - Wood, Susan (January 1976). "Locus Looks at Books". Locus. 9.

- Wood, Susan (June 1977). "Trade Paperbacks". Delap's F and SF Review: 35–36.

- Zelazny, Roger (1976). Bridge of Ashes. New York: Signet/New American Library. ISBN 0-451-15561-0.

- Zelazny, Roger (1989). Bridge of Ashes. New York: Signet/New American Library. ISBN 0-451-15561-0.

External links

- "Author Information: Roger Zelazny". Internet Book List. 2008. Archived from the original on 20 March 2013. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- "Bibliography: Bridge of Ashes". Internet Speculative Fiction Data Base. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- "Bridge of Ashes". Open Library. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- Bridge of Ashes. Worldcat. OCLC 4491813.

- "Exhibitions/Science Fiction Hall of Fame: Roger Zelazny". EMP Museum. Archived from the original on 22 July 2012. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- "Roger Zelazny". Locus Index to SF Awards. Archived from the original on 16 October 2012. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- "Roger Zelazny – Summary Bibliography". Internet Speculative Fiction Data Base. Retrieved 26 February 2013.