Brittenburg

Brittenburg was a Roman ruin site west of Leiden between Katwijk aan Zee and Noordwijk aan Zee, presumably identical to the even older Celtic Lugdunum fortress.[1] The site is first mentioned in 1401, was uncovered more completely by storm erosion in 1520, 1552 and 1562, and has subsequently been entirely eroded away. When built, it was located at the mouth of the Oude Rijn (old river Rhine), which has since moved. The site was about a kilometre west of the European Space Research and Technology Centre, now offshore in the North Sea).

History

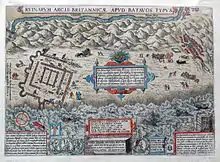

The word dunum, traceable in Gaelic place names in the present day (Dundalk, Dunrobin Castle) and meaning "fortress" or "castle", is a typically Celtic element in European place-names. The site, known as "Brittenburg", was still visible in the dunes in the fourteenth century, but the gradual advance of the sea made the ruins lie on the beach in the sixteenth and seventeenth century. Today, they would be somewhere in the Rhine estuary, inaccessible to archaeological research.[2] All that remains is a small set of finds, collected in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and a famous map by Ortelius. A copy of an old Roman map Tabula Peutingeriana shows Brittenburg as Lugduno; on the coast and with two towers. Eastwards from that point, two roads run towards Noviomagi (Nijmegen). Along the northern route, the following towns can be seen: Pretorium Agrippine (Valkenburg (South Holland)), Matilone (Leiden), Albanianis (Alphen aan den Rijn), Nigropullo (Zwammerdam), and Lauri (Woerden). All of these locations are situated on the Oude Rijn. The southern route begins with the town Forum Hadriani (Voorburg), shown directly south of Matilone. These towns were connected by the Fossa Corbulonis or Corbulo-canal.

The first mention of the Brittenburg in a Dutch text is in a poem of Willem van Hildegaersberch in 1401, who called it Borch te Bretten. In 1490 there is also a mention of the visibility of the "burg te Britten". It was uncovered in 1520 when a storm exposed the whole complex and Roman artifacts (mainly stones and coins), were found. Some coins were dated, with the latest date being 270. The oldest picture of the Brittenburg is a woodcut (identified by Leiden professor Jan Hendrik Holwerda, curator of the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden) by Abraham Ortelius in 1562 for Lodovico Guicciardini's first edition of The Low Countreys, printed in 1589 by Christophe Plantin in Antwerp. This woodcut was replaced in later editions with an engraving. The oldest picture was used later by Zacharias Heyns (1598, 1599) and Hermann Moll (1734, 1736). It concerns a land surveyor's draft (trigonometry), in which the distance from the ruins (by that time in the North Sea and only visible at low tide) westward to the church of Katwijk is mentioned, namely 1,200 'schreden' (= 1,080 meters). Brittenburg was part of the Roman border defense (limes), as the guard post (castellum) called Lugduno, the westernmost position situated along the Old Rhine, which formed the northern frontier of the Roman province Germania Inferior. Given the square shape of the inner structure, the Brittenburg was probably a lighthouse after the model of the lighthouse of Ostia Antica with a height of about 60 meters and a basis of 72 x 72 meters. Some historians also see a granary in the plan, but for this a drier, more inland location would have made more sense.

Structures

Burcht te Bretten

There has been a lot of confusion about the terms Brittenburg and Lugdunum Batavorum. The mysterious 'burcht te Bretten', a castle situated supposedly somewhere around Leiden (Bretten is the oldest name for the area between Leiden and the North Sea), has been sought since the Middle Ages. When the remains at Katwijk were rediscovered in 1520, they were (incorrectly) called Brittenburg for this reason. There were many burchts in this area that fell into disuse and were later torn down to reuse the stones in construction.

Burcht van Leiden

When the Tabula Peutingeriana was discovered by Conrad Celtes around 1500, Leiden scholars assumed that an old shell keep in the city center called the Burcht van Leiden, at the spot where the Leidse Rijn met the Oude Rijn, was Lugduno. This caused Leiden to bill itself (incorrectly) Lugdunum Batavorum for centuries during the Early Modern period. The Latin name of Leiden University is Academia Lugduno-Batava. The Batava was only added to distinguish Leiden from another Lugdunum.

The name is doubly unfortunately chosen, as those same scholars also assumed that Leiden was located within the old Batavia (region), which was in fact much further east, near Germany. Lugdunum was actually in the territory of the Cananefates, not the Batavi. Today Leiden is associated with the town Matilone on the tabula, and even that spot is considered to be a location somewhat eastwards of the Burcht van Leiden, at the site of the former monastery Roomburg.

Tower of Kalla

The Roman historian Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus wrote a story about the emperor Caligula, who, as if collecting spoils from war, commanded his men to collect shells.[3] It is commonly believed that Caligula declared war on Neptune here, but this myth comes not from Suetonius but Robert Grave's I, Claudius. Furthermore, it is possible that Suetonius was purposely manipulating the facts to make Caligula seem worse by playing off the word musculus's double meaning as both "seashell" and "mantlet," a type of military shield.[4]

Suetonius does include, however, that Caligula built a lighthouse as a victory monument, which resulted in an early modern quest for said lighthouse. In the 16th century, when many early tourists came to see the Brittenburg at low tide, people from Katwijk reported that their fishing nets were regularly stuck behind the stones of what they called "Kalla's tower" (Kalla = Caligula). This story of Caligula is probable, because a wine barrel was found originating from his personal vineyard in this area.[5]

Valkenburg

Considered to be part of Lugdunum, the Roman army supply base Praetorium Agrippinae, modern Valkenburg, is said to have been founded by Caligula. Modern archeologists have found traces of Roman infrastructure and have installed ways to see these in the modern landscape.

New Brittenburg

South east of the Brittenburg is now the sole reminder of the ancient structure: the bus stop Nieuw Brittenburg (New Brittenburg), the main bus stop for the city centre and the beach of Katwijk.

References

- Ephorus of Cyme

- D. Parleviet, "De Brittenburg voorgoed verloren", Westerheem 51.3 (2002).

- Suetonius, Life of Caligula 46

- "musculus - Wiktionary". en.wiktionary.org. Retrieved 2021-01-20.

- Simon Wynia, "Gaius Was Here: The Emperor Gaius' Preparations for the Invasion of Britannia: New Evidence", in H. Sarfatij, W. J. H. Verwers, and P. J. Woltering, ed., In Discussion with the Past: Archaeological Studies presented to W. A. van Es (Amersfoort, 1999).

- Brittenburg, raadsels rond een verdronken ruïne, H. Dijkstra and F.C.J. Ketelaar, Fibulareeks 2, Uitg. C.A.J. van Dishoeck, Bussum, 1975.

- De Brittenburg voorgoed verloren, D. Parleviet, in Westerheem 51/3, 2002.